The Economist

The Economist is a weekly news and international affairs publication owned and edited in London, UK. Although The Economist calls itself a newspaper, it is printed in magazine form on glossy paper, like a news magazine. It has been in continuous publication since September 1843. As of 2007, its average circulation topped 1.3 million copies a week, about half of which are sold in North America. Subjects covered include international news, economics, politics, business, finance, science and technology, and the arts. The publication is targeted at the high-end "prestige" segment of the market and counts among its audience influential business and government decision makers. The paper takes a strongly argued editorial stance on many issues, especially its support for free trade and fiscal conservatism.

Ownership

The Economist is a wholly owned subsidiary of The Economist Group. One half of The Economist Group is owned by private shareholders, including members of the Rothschild banking family of England (Sir Evelyn de Rothschild was Chairman of the company from 1972 to 1989), and the other half by the Financial Times, a subsidiary of The Pearson Group. The editorial independence of The Economist is strictly upheld. An independent trust board, which has power to block any changes of the editor, exists to ensure this.

The publication interests of the group include the CFO brand family as well as European Voice and Roll Call (known as "the Newspaper of Capitol Hill" in Washington, D.C.). Another part of the group is The Economist Intelligence Unit, a research and advisory company providing country, industry, and management analysis worldwide. Since 1928, half the shares of The Economist Group have been owned by the Financial Times, a subsidiary of Pearson PLC, and the other half by a group of independent shareholders, including many members of the staff. The editor's independence is guaranteed by the existence of a board of trustees, which formally appoints him and without whose permission he cannot be removed.

History

The Economist was founded by Scottish hat maker James Wilson in 1843. Wilson wanted a newspaper to advocate free trade, which The Economist still does.[1] The August 5, 1843 prospectus for the newspaper[2] enumerated 13 areas of coverage that its editors wanted the newspaper to focus on:

- Original leading articles, in which free-trade principles will be most rigidly applied to all the important questions of the day.

- Articles relating to some practical, commercial, agricultural, or foreign topics of passing interest, such as foreign treaties.

- An article on the elementary principles of political economy, applied to practical experience, covering the laws related to prices, wages, rent, exchange rate, revenue, and taxes.

- Parliamentary reports, with particular focus on commerce, agriculture, and free trade.

- Reports and accounts of popular movements advocating free trade.

- General news from the Court, the London Metropolis, the English Provinces, Scotland, and Ireland.

- Commercial topics such as changes in fiscal regulations, the state and prospects of the markets, imports and exports, foreign news, the state of the manufacturing districts, notices of important new mechanical improvements, shipping news, the money market, and the progress of railways and public companies.

- Agricultural topics, including the application of geology and chemistry; notices of new and improved implements, state of crops, markets, prices, foreign markets and prices converted into English money; from time to time, in some detail, the plans pursued in Belgium, Switzerland, and other well-cultivated countries.

- Colonial and foreign topics, including trade, produce, political and fiscal changes, and other matters, including exposés on the evils of restriction and protection, and the advantages of free intercourse and trade.

- Law reports, confined chiefly to areas important to commerce, manufacturing, and agriculture.

- Books, confined chiefly, but not so exclusively, to commerce, manufacturing, and agriculture, and including all treatises on political economy, finance, or taxation.

- A commercial gazette, with prices and statistics of the week.

- Correspondence and inquiries from the newspaper's readers.

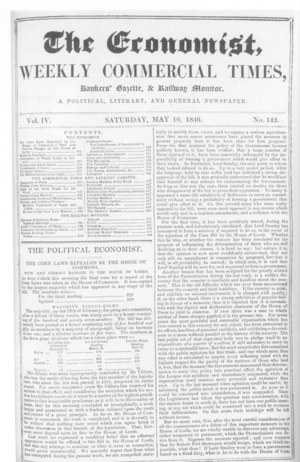

The first issue was published on September 2, 1843, under the name The Economist, with the subtitle "Or the Political, Commercial, Agricultural, and Free-trade Journal.[3] In 1845, during Railway Mania, The Economist changed its name to The Economist, Weekly Commercial Times, Bankers' Gazette, and Railway Monitor. A Political, Literary and General Newspaper.[4]

James Wilson served as editor-in-chief and sole proprietor of the paper for sixteen years. In 1860, Walter Bagehot, Wilson's son-in-law, succeeded him as editor of The Economist. After taking over Bagehot expanded the publication's reporting on the United States and on politics, and is considered to have increased its influence among policymakers. He served as editor until his death in 1877. The paper's most famous nineteenth century editor, Bagehot aimed for it "to be conversational, to put things in the most direct and picturesque manner, as people would talk to each other in common speech, to remember and use expressive colloquialisms."[5] That remains the style of the paper today.

After Bagehot's death, the next great editor was Walter Layton, whose succeeded in having the paper "read widely in the corridors of power abroad as well as at home" even if critics said it was "slightly on the dull side of solid".[6] Layton's successor, Geoffrey Crowther, developed and improved the coverage of foreign affairs, especially American, and of business. Crowther's great innovation was to start a section devoted to American affairs, which he did in 1941, after the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor. The aim of this section was to educate the British readership who, Crowther believed, needed to know more about the United States. It did, however, became the base for the paper's increase in American circulation that began in the 1970s.

Sales inside North America are 53 percent of its total, with sales in the UK making up 14 percent of the total and continental Europe 19 percent. The Economist claims sales, both by subscription and on newsstands, in 206 countries.

Opinions

When the newspaper was founded, the term "economism" denoted "economic liberalism" in the rest of the world (and historically in the United States as well). The Economist generally supports free markets, and opposes socialism. It is in favor of globalization and free immigration. Economic liberalism is generally associated with the right, but is now favored by some traditionally left-wing parties. It also supports social liberalism, which is often seen as left-wing, especially in the United States. This contrast derives in part from The Economist's roots in classical liberalism, disfavoring government interference in either social or economic activity. According to former editor Bill Emmott, "the Economist's philosophy has always been liberal, not conservative."[7] However, the views taken by individual contributors are quite diverse.

The Economist has endorsed both the Labour Party and the Conservative Party in recent British elections, and both Republican and Democratic candidates in the United States.

The Economist has frequently criticized figures and countries deemed corrupt or dishonest. For example, it gave editorial support for the impeachment of Bill Clinton. In recent years, for example, it has been critical of Silvio Berlusconi, Italy's former Prime Minister, who dubbed it The Ecommunist;[8] Laurent Kabila, the late president of the Democratic Republic of Congo; and Robert Mugabe, the head of government in Zimbabwe. The Economist also called for Donald Rumsfeld's resignation after the emergence of the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse.[9] Although The Economist supported George W. Bush's election campaign in 2000 and supported the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the editors backed John Kerry in the 2004 election.[10] The paper has also supported some left-wing issues such as progressive taxation, criticizing the United States tax model, and supported some government regulation on health issues (such as smoking in public areas) and income inequality (higher taxes for the wealthy), as long as it is done lightly. The Economist has consistently favored guest worker programs and amnesties, notably, in a 2006, article entitled "Sense not Sensenbrenner."[11]

Tone and voice

According to its contents page, the goal of The Economist' is "to take part in a severe contest between intelligence, which presses forward, and an unworthy, timid ignorance obstructing our progress." The Economist does not print bylines identifying the authors of articles. In their own words: "It is written anonymously, because it is a paper whose collective voice and personality matter more than the identities of individual journalists."[5] Where needed, references to the author within the article are made as "your correspondent."

Articles often take a definite editorial stance and almost never carry a byline. This means that no specific person or persons can be named as the author. Not even the name of the editor is printed in the issue. It is a longstanding tradition that an editor's only signed article during his tenure is written on the occasion of his departure from the position. The author of a piece is named in certain circumstances: when notable persons are invited to contribute opinion pieces; when Economist writers compile surveys; and to highlight a potential conflict of interest over a book review. The names of Economist editors and correspondents can be located, however, via the staff pages of the website.

The editorial staff enforces a strictly uniform voice throughout the magazine.[12] As a result, most articles read as though they were written by a single author, displaying dry, understated wit, and precise use of language, a trait which many define as "classically British."

The magazine's treatment of economics presumes a working familiarity with fundamental concepts of classical economics. For instance, it does not explain terms like "invisible hand," macroeconomics, or demand curve, and may take just six or seven words to explain the theory of comparative advantage. However, articles involving economics do not presume any formal training on the part of the reader, and aim to be accessible to the reasonably educated and intelligent layman. The newspaper usually does not translate short French quotes or phrases, and sentences in Ancient Greek or Latin are not uncommon.[13] It does, however, almost always describe the business of an entity whose name it prints, even if it's a well-known entity; for example, in place of "Goldman Sachs," The Economist might write "Goldman Sachs, an investment bank."

The paper strives to be well-rounded. As well as financial and economic issues, it reports on science, culture, language, literature, and art, and is careful to hire writers and editors who are well-versed in these subjects.

The publication displays a sense of whimsy. Many articles include some witticism, image captions are often humorous and the letters section usually concludes with an odd or light-hearted letter. These efforts at humor have sometimes had a mixed reception.

Features

The magazine consciously adopts an internationalist approach, noting that over 80 percent of its readership is from outside the UK, its country of publication. The Economist's primary focus is world news, politics, and business, but it also runs regular sections on science and technology as well as books and the arts. Every two weeks, the newspaper includes, as an additional section, an in-depth survey of a particular business issue, business sector, or geographical region. Every three months, The Economist publishes a technology survey.

It has a trademark tight writing style that is famous for putting the maximum amount of information into a minimum of column inches.[14] Since 1995, The Economist has published one obituary every week, of a famous (or infamous) person from any field of endeavor.

The Economist is widely known for its "Big Mac index," which uses the price of a Big Mac hamburger sold by McDonald's in different countries as an informal measure of exchange rates. While whimsical, exchange rates in Western countries have been more likely to adjust to the "Big Mac index" than vice-versa.

Each opinion column in the newspaper is devoted to a particular area of interest. The names of these columns reflect their area of concentration:

- Bagehot (Britain)—named for Walter Bagehot, nineteenth century British constitutional expert and early editor of The Economist

- Charlemagne (Europe)—named for Charlemagne, founder of the Frankish Empire

- Lexington (United States)—named for Lexington, Massachusetts, the site of the beginning of the American War of Independence

- Buttonwood (finance)—named for the buttonwood tree where early Wall Street traders gathered. Until September 2006 this was available only as an online column, but is now included in the print edition

Two other regular columns are:

- Face Value: About prominent people in the business world

- Economics Focus: A general economics column frequently based on academic research

The Economist frequently receives letters from senior businesspeople, politicians and spokespeople for government departments, nongovernmental organizations, and lobbying groups. Letters published are typically between 150-200 words long. While well-written or witty responses from anyone will be considered, controversial issues will frequently produce a torrent of letters. For example, the survey of Corporate Social Responsibility, published January 2005, produced largely critical letters from Oxfam, the UN World Food Programme, UN Global Compact, the Chairman of BT, an ex-Director of Shell and the UK Institute of Directors.[15]

The Economist sponsors yearly "Innovation Awards," in the categories of bioscience, computing and communications, energy and the environment, social and economic innovation, business-process innovation, consumer products, and a special “no boundaries” category. The newspaper is also a co-sponsor of the Copenhagen Consensus, a project for the promotion of global welfare.

The Economist also produces the annual The World in [Year] publication.

Censorship

Sections of The Economist criticizing authoritarian regimes, such as the China, are frequently removed from the newspaper by the authorities in those countries. Despite having its Asia-Pacific office in Singapore, The Economist regularly had difficulties with the leadership there and was sued successfully for libel on a number of occasions.[16]

In 2006, Iran banned the sale of The Economist because of a map labeling the Persian Gulf as the "Gulf." Iran's action can be put into context within the larger issue of the Persian Gulf naming dispute.[17]

Robert Mugabe's authoritarian government in Zimbabwe went further, and imprisoned Andrew Meldrum, The Economist's correspondent there. The government charged him with violating a statute against "publishing untruth" for writing that a woman was decapitated by Mugabe supporters. The decapitation claim was retracted and allegedly fabricated by the woman's husband. The correspondent was later acquitted, only to receive a deportation order.[18]

Criticism

The Economist has been criticized for its moral beliefs influenced by John Stuart Mill, such as supporting the legalization of prostitution and same-sex marriage.[13] Others have been critical of The Economist's writing style. It has been said that the writers of each article are too confident in their opinions, so as to stifle debate and leave the reader unable to question the material therein.[19]

Notes

- ↑ The Economist, About Our History. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- ↑ The Economist, Prospectus. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ↑ The Economist, Our First Issue. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ↑ First Monday, The many paradoxes of broadband. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The Economist, About us. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Ruth D. Edwards, The Pursuit of Reason: The Economist 1843–1993 (Harvard Business School Press, 1995, ISBN 08758460840).

- ↑ The Guardian, Time for a referendum on the monarchy. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ↑ Indy Media, Report of Rome anti-war demo on Saturday 24 with photos. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ↑ The Economist, Resign Rumsfeld. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ↑ The Economist, Crunch time in America. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ↑ The Economist, Sense, not Sensenbrenner. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ↑ The Economist, Style guide. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mercatornet, The Economist's moral blinkers. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ↑ The Economist, The Economist style guide. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ↑ Business-humanrights.org, Compilation: Full text of responses to Economist survey on Corporate Social Responsibility (Jan-Feb 2005). Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ↑ Asia Times, Inconvenient truths in Singapore. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ↑ Jerusalem Post, Iran bans The Economist over map. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ↑ Reporters Without Borders, Guardian and RFI correspondent risks two years in jail. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ↑ Washington Post, The Economics of the Colonial Cringe. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Economist. 2005. The Economist Style Guide. Profile Books. ISBN 1861979169.

- Edwards, Ruth Dudley. 1995. The Pursuit of Reason: The Economist 1843–1993. Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 9780875846088.

- Hubback, David. 1985. No Ordinary Press Baron: A Life of Walter Layton. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0297784722.

External links

All links retrieved September 11, 2013.

- Economist.com – Official website of The Economist.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.