Stingray

| Stingray | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

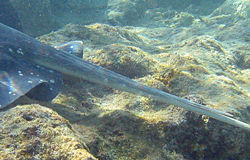

Bluespotted stingray, Taeniura lymma

| ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

See text for genera and species. |

Stingray is the common name for any of the various cartilaginous fish comprising the family Dasyatidae, characterized by enlarged and flat pectoral fins continuous with the side of the head, no caudal fin, eyes on the dorsal surface, and narrow, long, and whip-like tail, typically with one or more venomous spines. Marine, brackish water, and freshwater species are known.

Ecologically, stingrays are important components of aquatic food chains, consuming mollusks, crustaceans, tube anemones, amphipods, and small fish, while being preyed upon by a multitude of sharks, such as the white, tiger, and bull sharks, and even alligators in the case of freshwater species (Passarelli and Piercy 2008). While they provide some culinary value for humans, one of their chief values may be more internal—the wonder and beauty provided by their unique form, swimming behavior, and colors.

Overview and classification

Stingrays are members of the Chondrichthyes or "cartilaginous fishes," a major class of jawed fish that includes the sharks, rays, and skates. Members of Chondrichthyes are characterized by skeletons made of rubbery cartilage rather than bone, as in the bony fishes. The chondrichthyans have jaws, paired fins, paired nostrils, scales, and two-chambered hearts. Two subclasses of Chondrichthyes are recognized, Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, and skates) and Holocephali (chimaera, sometimes called ghost sharks).

Taxonomy for levels between Elasmobranchii and genera is unsettled, with diverse taxonomies. For example, some classifications consider the sharks a sister group with the rays and skates, placing these two groups into different superorders, while other classifications place the rays and skates as a subsection of the sharks (McEachran 2004). That is, some view sharks and rays together forming a monophyletic group, and sharks without rays a paraphyletic group, while others see sharks sharing a common ancestor with rays and skates as sister groups (Nelson 2004).

The same taxonomic diversity is apparent at the level of the family Dasyatidae. Dasyatidae is variously placed in the order Rajiformes (Agbayani 2004), or in the order Myliobatiformes (Passarelli and Piercy, 2008). This is because in some classifications the order Rajiformes is split into two or three orders, with Myliobatiformes being an extra order and including the traditional Rajiformes families of Dasyatidae (stingrays), Gymnuridae (butterfly rays), Mobulidae (Manta rays), Myliobatidae (eagle rays), and others (ITIS 2004).

Furthermore, what genera and families are included in Dasyatidae vary with taxonomic scheme. Nelson (1994) recognizes two subfamilies, Dasyatinae (stingrays or whiprays) and Potamotrygoninae (river sitngrays), and he recognizes nine genera, as does Agbayani (2004). ITIS (2004) elevates the second subfamily of river stingrays (which are the freshwater rays in South America) to the family level as Potamotrygonidae, recognizing six genera.

Unless otherwise stated, this article will follow the narrower view of Dasyatidae of ITIS (2004), which will be equivalent to subfamily Dasyatinae of Nelson (1994).

Description

In stingrays, as with all rays in the traditional order Rajiformes, the anterior edge of the pectoral fin, which is greatly enlarged, is attached to the side of the head anterior to the gill openings (Nelson 1994). They also have ventral gill openings, and the eyes and spiracles are on the dorsal surface (Nelson 1994). In addition, they lack an anal fin and lack a nictitating membrane with the cornea attached directly to the skin around the eyes (Nelson 1994).

In members of Dasyatidae—Subfamily Dasyatinae, in Nelson 1994—the disc is less than 1.3 times as broad as it is long (Nelson 1994). They lack a caudal fin and the tail is long, with the distance from the cloaca to the tip much longer than the breadth of the disc (Nelson 1994).

Dasyatids are common in tropical coastal waters throughout the world, and there are fresh water species in Asia (Himantura sp.), Africa, and Florida (Dasyatis sabina). Nelson (1994) reports that several tropical species of Dasyatidae (subfamily Dasyatinae) are known only from freshwater, and some marine species are found in brackish and freshwater on occasion.

Some adult rays may be no larger than a human palm, while other species, like the short-tail stingray, may have a body of six feet in diameter, and an overall length, including their tail, of fourteen feet. Stingrays can vary from gray to bright red in color and be plain or patterned. Dasyatids are propelled by motion of their large pectoral fin (commonly mistaken as "wings").

Their stinger is a razor-sharp, barbed, or serrated cartilaginous spine, which grows from the ray's whip-like tail (like a fingernail), and can grow as long as 37 centimeters (about 14.6 inches). On the underside of the spine are two grooves containing venom-secreting glandular tissue. The entire spine is covered with a thin layer of skin called the integumentary sheath, in which venom is concentrated (Meyer 1997). The venom contains the enzymes 5-nucleotidase and phosphodiesterase, which breakdown and kill cells; and the neurotransmitter serotonin, which provokes smooth-muscle contractions (Layton 2008). This venomous spine gives them their common name of stingrays (a compound of "sting" and "ray"), but the name can also be used to refer to any poisonous ray.

Stingrays may also be called the "whip-tailed rays," though this usage is much less common.

A group or collection of stingrays is commonly referred to as a "fever" of stingrays.

Feeding, predation, and stinging mechanism

Stingrays feed primarily on mollusks, crustaceans, and occasionally on small fish.

The flattened bodies of stingrays allow them effective concealment in sand. Smell and electro-receptors are used to locate prey, similar to those of sharks. Some sting rays' mouths contain two powerful, shell-crushing plates, while some species only have sucking mouth parts. Rays settle on the bottom while feeding, sometimes leaving only their eyes and tail visible. Coral reefs are favored feeding grounds and are usually shared with sharks during high tide.

Stinging mechanism

Dasyatids generally do not attack aggressively or even actively defend themselves. When threatened, their primary reaction is to swim away. However, when attacked by predators or stepped on, the barbed stinger in their tail is whipped up. This attack is normally ineffective against their main predator, sharks. The breaking of the stinger in defense is non-fatal to the stingray, as it will be regrown.

Depending on the size of the stingray, humans are usually stung in the foot region. Surfers or those who enter waters with large populations of stingrays have learned to slide their feet through the sand rather than stepping, as the rays detect this and swim away. Stamping hard on the bottom as one treads through murky water will also cause them to swim away. Humans who harass stingrays have been known to be stung elsewhere, sometimes leading to fatalities. Contact with the stinger causes local trauma (from the cut itself), pain and, swelling from the venom, and possible later infection from bacteria. Immediate injuries to humans include, but are not limited to, poisoning, punctures, severed arteries, and possibly death. Fatal stings are very rare. On September 4, 2006, Australian wildlife expert and television personality Steve Irwin was pierced in the chest by a stingray barb while snorkeling in Australia and died shortly after.

Treatment for stings includes application of near-scalding water, which helps ease pain by denaturing the complex venom protein, and antibiotics. Immediate injection of local anesthetic in and around the wound is very helpful, as is the use of opiates such as intramuscular pethidine. Local anesthetic brings almost instant relief for several hours. Any warm to hot fluid, including urine, may provide some relief. Vinegar and papain are ineffective. (Urine is a folk remedy for box jellyfish stings but is ineffective for such, whereas vinegar is effective for box jellyfish stings.) Pain normally lasts up to 48 hours, but is most severe in the first 30–60 minutes and may be accompanied by nausea, fatigue, headaches, fever, and chills. All stingray injuries should be medically assessed; the wound needs to be thoroughly cleaned, and surgical exploration is often required to remove any barb fragments remaining in the wound. Following cleaning, an ultrasound is helpful to confirm removal of all the fragments (Flint and Sugrue 1999). Not all remnants are radio-opaque; but X-ray radiography imaging may be helpful where ultrasound is not available.

Reproduction

Mating season occurs in the winter. When a male is courting a female, he will follow her closely, biting at her pectoral disc. During mating, the male will go on top of the female (his belly on her back) and put one of his two claspers into her vent (Martin 2008).

Most rays are ovoviviparous, bearing live young in "litters" of five to ten. The female holds the embryos in the womb without a placenta. Instead, the embryos absorb nutrients from a yolk sac, and after the sac is depleted, the mother provides uterine milk (Passarelli and Piercy 2008).

Stingrays and humans

In addition to their ecological role in aquatic food chains, stingrays offer a number of values to humans, in terms of food, various products, and ecotourism.

Although edible, stingrays are not a dietary staple and are not considered a high-quality food. However, they are consumed, including fresh, dried, and salted (McEachran 2004). Stingray recipes abound throughout the world, with dried forms of the wings being most common. For example, in Singapore and Malaysia, stingray is commonly barbecued over charcoal, then served with spicy sambal sauce. Generally, the most prized parts of the stingray are the wings, the "cheek" (the area surrounding the eyes), and the liver. The rest of the ray is considered too rubbery to have any culinary uses.

While not independently valuable as a food source, the stingray's capacity to damage shell fishing grounds can lead to bounties being placed on their removal.

The skin of the ray is rough and can be used as leather (McEachran 2004). The skin is used as an underlayer for the cord or leather wrap (ito) on Japanese swords (katanas) due to its hard, rough texture that keeps the braided wrap from sliding on the handle during use. Native American Indians used the spines of stingrays for arrowheads, while groups in the Indo-West Pacific used them as war clubs (McEachran 2004).

Stingrays are popular targets of ecotourism. Dasyatids are not normally visible to swimmers, but divers and snorkelers may find them in shallow sandy waters. Usually very docile, their usual reaction being to flee any disturbance. Nevertheless, certain larger species may be more aggressive and should only be approached with caution by humans, as the stingray's defensive reflex may result in serious injury or even death.

In the Cayman Islands, there are several dive sites called Stingray City, Grand Cayman, where divers and snorkelers can swim with large southern stingrays (Dasyatis Americana) and feed them by hand. There is also a "Stingray City" in the sea surrounding the Caribbean island of Antigua. It consists of a large, shallow reserve where the rays live, and snorkeling is possible. In Belize, off the island of Ambergris Caye there is a popular marine sanctuary called Hol Chan. Here divers and snorkelers often gather to watch stingrays and nurse sharks that are drawn to the area by tour operators who feed the animals.

Many Tahitian island resorts regularly offer guests the chance to "feed the stingrays and sharks." This consists of taking a boat to the outer lagoon reefs then standing in waist-high water while habituated stingrays swarm around, pressing right up against a person seeking food.

While most dasyatids are relatively widespread and unlikely to be threatened, there are several species (for example, Taeniura meyeni, Dasyatis colarensis, D. garouaensis, and D. laosensis) where the conservation status is more problematic, leading to them being listed as vulnerable or endangered by IUCN. The status of several other species are poorly known, leading to them being listed as data deficient.

Species

There are about seventy species, placed in seven genera:

- Genus Dasyatis

- Dasyatis acutirostra (Nishida & Nakaya, 1988).

- Red stingray, Dasyatis akajei (Müller & Henle, 1841).

- Southern stingray, Dasyatis americana (Hildebrand & Schroeder, 1928).

- Plain maskray, Dasyatis annotata (Last, 1987).

- Bennett's stingray, Dasyatis bennetti (Müller & Henle, 1841).

- Short-tail stingray or bull ray, Dasyatis brevicaudata (Hutton, 1875).

- Whiptail stingray, Dasyatis brevis (Garman, 1880).

- Roughtail stingray, Dasyatis centroura (Mitchill, 1815).

- Blue stingray, Dasyatis chrysonota (Smith, 1828).

- Diamond stingray, Dasyatis dipterura (Jordan & Gilbert, 1880).

- Estuary stingray, Dasyatis fluviorum (Ogilby, 1908).

- Smooth freshwater stingray, Dasyatis garouaensis (Stauch & Blanc, 1962).

- Sharpsnout stingray, Dasyatis geijskesi (Boeseman, 1948).

- Giant stumptail stingray, Dasyatis gigantea (Lindberg, 1930).

- Longnose stingray, Dasyatis guttata (Bloch & Schneider, 1801).

- Dasyatis hastata (DeKay, 1842).

- Izu stingray, Dasyatis izuensis (Nishida & Nakaya, 1988).

- Bluespotted stingray, Dasyatis kuhlii (Müller & Henle, 1841).

- Yantai stingray, Dasyatis laevigata (Chu, 1960).

- Mekong stingray, Dasyatis laosensis (Roberts & Karnasuta, 1987).

- Brown stingray, Dasyatis latus (Garman, 1880).

- Painted maskray, Dasyatis leylandi (Last, 1987).

- Longtail stingray, Dasyatis longa (Garman, 1880).

- Daisy stingray, Dasyatis margarita (Günther, 1870).

- Pearl stingray, Dasyatis margaritella (Compagno & Roberts, 1984).

- Dasyatis marianae (Gomes, Rosa & Gadig, 2000).

- Marbled stingray, Dasyatis marmorata (Steindachner, 1892).

- Pitted stingray, Dasyatis matsubarai (Miyosi, 1939).

- Smalleye stingray, Dasyatis microps (Annandale, 1908).

- Multispine giant stingray, Dasyatis multispinosa (Tokarev, 1959).

- Blackish stingray, Dasyatis navarrae (Steindachner, 1892).

- Common stingray, Dasyatis pastinaca (Linnaeus, 1758).

- Smalltooth stingray, Dasyatis rudis (Günther, 1870).

- Atlantic stingray, Dasyatis sabina (Lesueur, 1824).

- Bluntnose stingray, Dasyatis say (Lesueur, 1817).

- Chinese stingray, Dasyatis sinensis (Steindachner, 1892).

- Thorntail stingray, Dasyatis thetidis (Ogilby, 1899).

- Tortonese's stingray, Dasyatis tortonesei (Capapé, 1975).

- Cow stingray, Dasyatis ushiei (Jordan & Hubbs, 1925).

- Pale-edged stingray, Dasyatis zugei (Müller & Henle, 1841).

- Genus Himantura

- Pale-spot whip ray, Himantura alcockii (Annandale, 1909).

- Bleeker's whipray, Himantura bleekeri (Blyth, 1860).

- Freshwater whipray, Himantura chaophraya (Monkolprasit & Roberts, 1990).

- Dragon stingray, Himantura draco (Compagno & Heemstra, 1984).

- Pink whipray, Himantura fai (Jordan & Seale, 1906).

- Ganges stingray, Himantura fluviatilis (Hamilton, 1822).

- Sharpnose stingray, Himantura gerrardi (Gray, 1851).

- Mangrove whipray, Himantura granulata (Macleay, 1883).

- Himantura hortlei Last, Manjaji-Matsumoto & Kailola, 2006.[1]

- Scaly whipray, Himantura imbricata (Bloch & Schneider, 1801).

- Pointed-nose stingray, Himantura jenkinsii (Annandale, 1909).

- Kittipong's stingray, Himantura kittipongi

- Marbled freshwater whip ray, Himantura krempfi (Chabanaud, 1923).

- Himantura lobistoma Manjaji-Matsumoto & Last, 2006.[2]

- Blackedge whipray, Himantura marginatus (Blyth, 1860).

- Smalleye whip ray, Himantura microphthalma (Chen, 1948).

- Marbled whipray, Himantura oxyrhyncha (Sauvage, 1878).

- Pacific chupare, Himantura pacifica (Beebe & Tee-Van, 1941).

- Himantura pareh (Bleeker, 1852).

- Round whip ray, Himantura pastinacoides (Bleeker, 1852).

- Chupare stingray, Himantura schmardae (Werner, 1904).

- White-edge freshwater whip ray, Himantura signifer (Compagno & Roberts, 1982).

- Black-spotted whipray, Himantura toshi (Whitley, 1939).

- Whitenose whip ray, Himantura uarnacoides (Bleeker, 1852).

- Honeycomb stingray, Himantura uarnak (Forsskål, 1775).

- Leopard whipray, Himantura undulata (Bleeker, 1852).

- Dwarf whipray, Himantura walga (Müller & Henle, 1841).

- Genus Makararaja

- Makararaja chindwinensis Roberts, 2007[3]

- Makararaja chindwinensis Roberts, 2007[3]

- Genus Pastinachus

- Cowtail stingray, Pastinachus sephen (Forsskål, 1775).

- Pastinachus solocirostris (Last, Manjaji & Yearsley, 2005).[4]

- Genus Pteroplatytrygon

- Pelagic stingray, Pteroplatytrygon violacea (Bonaparte, 1832).

- Pelagic stingray, Pteroplatytrygon violacea (Bonaparte, 1832).

- Genus Taeniura

- Round stingray, Taeniura grabata (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1817).

- Bluespotted ribbontail ray, Taeniura lymma (Forsskål, 1775).

- Blotched fantail ray, Taeniura meyeni (Müller & Henle, 1841).

- Genus Urogymnus

- Porcupine ray, Urogymnus asperrimus (Bloch & Schneider, 1801).

- Thorny freshwater stingray, Urogymnus ukpam (Smith, 1863).

Notes

- ↑ P.R. Last, M. Manjaji-Matsumoto, and P.J. Kailola, Himantura hortlei n. sp., a new species of whipray (Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae) from Irian Jaya, Indonesia, Zootaxa 1239(2006): 19-34. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ↑ M. Manjaji-Matsumoto and P. J. Last, Himantura lobistoma, a new whipray (Rajiformes: Dasyatidae) from Borneo, with comments on the status of Dasyatis microphthalmus, Ichthyological Research 53(3)(2006): 291ff. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ↑ T.R. Roberts, Makararaja chindwinensis, a new genus and species of freshwater dasyatidid stingray from upper Myanmar, The Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society 54(2006): 285–293.

- ↑ P.R. Last, B. M. Manjaji, and G.K. Yearsley, Pastinachus solocirostris sp. nov., a new species of Stingray (Elasmobranchii: Myliobatiformes) from the Indo-Malay Archipelago, Zootaxa 1040(2005): 1-16. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agbayani, E. 2004. Family Dasyatidae: Stingrays. In R. Froese and D. Pauly (eds.), FishBase. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- Flint, D., and W. Sugrue. 1999. Stingray injuries: A lesson in debridement. New Zealand Med J 112(1086): 137-8. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2003a. Dasyatidae Jordan, 1888. ITIS Taxonomic Serial No.: 160946. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2003b. Rajiformes. ITIS Taxonomic Serial No.: 160806. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2004. Myliobatiformes. ITIS Taxonomic Serial No.: 649685 . Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- Layton, J. 2008. How do stingrays kill? How Stuff Works. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- Martin, R. A. 2008. Biology of sharks and rays: Stingray City limits. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- McEashran, J. D. 2004. Rajiformes. In B. Grzimek, S. F. Craig, D. A. Thoney, N. Schlager, and M. Hutchins. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Detroit, MI: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 0787657786.

- Meyer, P. 1997. Stingray injuries. Wilderness Environ Med 8(1): 24-8.

- Nelson, J. S. 1994. Fishes of the World, 3rd edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471547131.

- Passarelli, N., and A. Piercy. 2008. Atlantic stingray. Florida Museum of Natural History, Ichthyology Department. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.