Shakers

The Shakers are a Christian sect, an offshoot of the Religious Society of Friends (or Quakers), originating in Manchester, England in the late eighteenth century. Strict believers in celibacy, Shakers maintained their numbers through conversion and adoption. Once boasting thousands of adherents, as of 2006 the Shakers numbered only four people living in Sabbathday Lake, Maine.[1]

The Shakers are famous for their ecstatic religious dances and work ethic, as well as their eschewal of marriage.

Origin of the name

The name Shakers, originally pejorative, was applied by outsiders as a mocking description of the group's rituals of trembling, shouting, dancing, shaking, singing, and glossolalia (speaking in strange and unknown languages). The first documented use of the term comes from a British newspaper reporter who wrote in 1758 that the worshippers rolled on the floor and spoke in tongues.

History

The Shakers were an offshoot of English Quakers who had adopted some of the doctrines of worship followed by the Camisards (a French religious sect living in England). Under the leadership of James and Jane Wardley, husband and wife, the Shakers became known for their intense, ecstatic worship. The Wardleys' followers writhed and trembled, purportedly under the influence of the Holy Spirit, so that they gained the name Shakers; their trances and visions, their jumping and dancing, were like those of many other sects, such as the Low Countries' dancers of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the French Convulsionnaires of 1720–1770, or the Welsh Methodist Jumpers. Followers quickly adopted the derogatory nickname, Shaking Quakers, which had been given to them by their many detractors.

Ann Lee

Under the leadership of Ann Lee, beginning in 1774, the work ethic and rejection of marriage for which they became known began to typify the movement. She joined the Wardleys in 1758.

Although a believer in celibacy, she had, at her parents' urging, married Abraham Stanley (Standley, or Standerin), and bore him four children, all of whom died in infancy. She was miserable in marriage, and by 1770 had begun to insist that the institution was not compatible with the Kingdom of God. Like many others in the Quaker tradition, she believed in and taught her followers that it is possible to attain perfect holiness. Like her predecessors the Wardleys, she taught that the demonstrations of shaking and trembling were caused by sin being purged from the body by the power of the Holy Spirit, purifying the worshiper. Distinctively, the followers of Mother Ann came to believe that she embodied all the perfections of God in female form.

She rose to prominence in the movement through her dramatic urging of the Believers to preach more publicly concerning the Kingdom of God, and to attack sin more boldly and unconventionally. She was frequently imprisoned for breaking the Sabbath by dancing and shouting, and for blasphemy. While in prison in Manchester for 14 days, she said she had a revelation that "a complete cross against the lusts of generation, added to a full and explicit confession, before witnesses, of all the sins committed under its influence, was the only possible remedy and means of salvation."

After this, she was chosen by the society as "Mother in spiritual things" and called herself "Ann, the Word" and also "Mother Ann." Another revelation bade her take a select band to America. Mother Ann arrived on August 6, 1774 in New York City, and in 1776 the Shakers settled in Niskayuna, New York (then in the township of Watervliet), near Albany, where a unique community life began to develop and thrive.

First Shaker society

The village was divided into groups or "families" that were named for points on the compass. Each house was divided so that men and women did everything separately. They used different staircases, doors and even sat on opposite sides of the room. The men and women were segregated to prevent them from touching one another during the epileptic-like fits that they fell into during worship. The elders would watch over them through the windows, to make sure no physical contact happened.

A spiritualistic revival in the neighboring town of New Lebanon sent many penitents to Watervliet, who accepted Mother Ann's teachings. They organized in 1787 the New Lebanon Society, the first Shaker Society, at New Lebanon (since 1861 called Mt. Lebanon), Columbia county, New York. The Society at Watervliet, organized immediately afterwards, and the New Lebanon Society formed a bishopric. The Watervliet members, as pacifists and non-jurors, had got into trouble during the American War of Independence; in 1780 the Board of Elders were imprisoned, but all except Mother Ann were speedily set free, and she was released in 1781.

Communalism under Joseph Meacham

Between 1781 and 1783 the Mother, with chosen elders, visited her followers in New York, Massachusetts and Connecticut. She died in Watervliet, New York on September 8, 1784. Thereafter, James Whittaker (1751-1787) led the Believers for three years. On his death he was succeeded by Joseph Meacham (1742–1796), who had been a Baptist minister in Enfield, Connecticut, and had, second only to Mother Ann, the spiritual gift of revelation. Under his rule and that of Lucy Wright (1760–1821), who shared the headship with him during his lifetime and then for 25 years ruled alone, the organization of the Shakers and, particularly, a rigid communalism (religious communism), began. By 1793 property had been made a "consecrated whole" in the different communities, but a "noncommunal order" also had been established, in which sympathizers with the principles of the Believers lived in families. The Shakers never forbade marriage, but refused to recognize it as a Christian institution since the second coming in the person of Mother Ann, and considered it less perfect than the celibate state. Shaker communities in this period were established in 1790 at Hancock, West Pittsfield, Massachusetts; in 1791 at Harvard, Massachusetts; in 1792 at East Canterbury, New Hampshire (or Shaker Village); and in 1793 at Shirley, Massachusetts; at Enfield, Connecticut (then also known as Shaker Station); at Enfield, New Hampshire (or "Chosen Vale"); at Tyringham, Massachusetts, where the Society was afterwards abandoned, its members joining the communities in Hancock and Enfield; at New Gloucester, Maine (since 1890: "Sabbathday Lake"); and at Alfred, Maine, where, more than anywhere else among the Shakers, spiritualistic healing of the sick was practiced. In Kentucky and Ohio, Shakerism entered after the Cane Ridge, Kentucky revival of 1800–1801, and in 1805–1807 Shaker societies were founded at South Union, Logan county, Kentucky, and Pleasant Hill, Kentucky, Mercer County, Kentucky.

Expansion and contraction

An important figure in the revival involved Richard McNemar, a Presbyterian, who had broken with his Church because of his Arminian tendencies and had established the quasi-independent Turtle Creek Church. McNemar was converted by Shaker missionaries in 1805, and many of his parishioners joined him to form the Union Village community in Turtlecreek Township, Warren County, Ohio, four miles west of Lebanon. McNemar was a favorite of Lucy Wright, who gave him the spiritual name Eleazer Riotht, which he changed to Eleazer Wright; he wrote The Kentucky Revival (Cincinnati, 1807), probably the earliest defense of Shakerism, and a poem, entitled A Concise Answer to the General Inquiry Who or What are the Shakers (1808).

In 1811, a community settled at Busro on the Wabash in Indiana; but it was soon abandoned and its members went to Ohio and to Kentucky. In Ohio later communities were formed at Watervliet, Montgomery and Greene counties, and at Whitewater, Butler and Hamilton counties. In New York, the communal property at Sodus Bay was sold in 1828 and the community removed to Groveland, or Sonyea; their land was sold to the state and the few remaining members went to Watervliet. A short-lived community at Canaan, was merged into the communities in Mount Lebanon (in New Lebanon) and Enfield, Connecticut.

The peak of the movement was probably reached between 1830 and 1850 at about 6,000 members. The numerical strength of the sect decreased rapidly, probably from 4,000 to 1,000 from 1887 to 1908, and there has been little effort made to plant new communities. The Mount Lebanon Society in 1894 established a colony at Narcoossee, Florida; the attempt of the Union Village Society in 1898 to plant a settlement at White Oak, Georgia, was unsuccessful. In 1910 the Union Village Society went into the hands of a receiver.

At various times, the Shakers had 18 major communities in eight states and six smaller communities in Florida and Indiana. The city of Shaker Heights, Ohio, population 29,000, a suburb of Cleveland, was originally a Shaker settlement.

Today there are very few remaining Shakers left. They reside in Sabbathday Lake, Maine.

Distinct Practices

The Shakers did not believe in procreation so therefore had to adopt a child if they wanted one. Another way they could expand their community's population was to allow converts into the Shaker society to live and function as one. When Shaker boys reached the age of 21, they were given the choice to leave the Shaker religion and go their own separate way or to continue on as a Shaker. The Shakers lived in "families" sharing a large house with separate entrances for each family within the "family"; thus the families were exclusively male or female — the sexes were segregated into separate living areas.

The Shakers struggled with complex human problems that have no simple answers, and they managed to set up and sustain a distinctive way of life.

Revelations and visions

A peculiar, intense kind of spirituality began to develop under this unique arrangement. A period of spiritual manifestations among the Believers began in 1837 and lasted through 1847. Children spoke of visits to cities in the spirit realm and brought messages to the community which they received from Mother Ann. In 1838 the gift of tongues was manifested and sacred places were set aside in each community, with names like Holy Mount; but in 1847 the spirits, after warning, left the Believers. The theology of the denomination is based on the idea of the dualism of God: the creation of man as male and female "in our image" showing the bi-sexuality of the Creator; in Jesus, born of a woman, the son of a Jewish carpenter, were the male manifestation of Christ and the first Christian Church; and in Mother Ann, daughter of an English blacksmith, were the female manifestation of Christ and the second Christian Church — she was the Bride ready for the Bridegroom, and in her the promises of the Second Coming were fulfilled. Adam's sin was in sexual impurity; marriage is done away with in the body of the Believers in the Second Appearance, who must pattern after the Kingdom in which there is no marriage or giving in marriage. The four virtues are virgin purity; Christian communism; confession of sin, without which none can become Believers; and separation from the world. Their insistence on the bi-sexuality of God and their reverence for Mother Ann have made them advocates of gender equality. Their spiritual directors are elders and "eldresses," and their temporal guides are deacons and deaconesses in equal numbers.

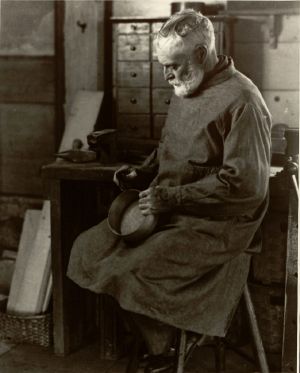

Culture of work

The Shakers believed in the value of hard work and kept comfortably busy. Each member learned a craft and did chores. Mother Ann said, :"Labor to make the way of God your own; let it be your inheritance, your treasure, your occupation, your daily calling." :"Do your work as though you had a thousand years to live and as if you were to die tomorrow."

- "Put your hands to work, and your heart to God."

The egalitarianism of the Believers was an economic success, and their cleanliness, honesty and frugality received the highest praise. They made leather, sold herbs and garden seeds, produced "apple-sauce," and wove linen. They were also known for a style of furniture, known as Shaker furniture. It was plain in style, durable, and functional. Shaker chairs were usually mass-produced since a great number of them were needed to seat all the Shakers in a community. Around the time of the American Civil War, the Shakers at Mount Lebanon, NY, greatly increased their production and marketing of Shaker chairs. They were so successful that several furniture companies produced their own versions of "Shaker" chairs. Because of the quality of their craftsmanship, original Shaker furniture is costly—up to US$100,000.

Shakers worshipped in plain meetinghouses where they marched, sang songs, danced, twitched and shouted. Many outsiders who witnessed Shaker worship services considered them heretics and protested in front of their places of worship. Mother Ann was arrested several times for disturbing the peace. Early Shaker worship services were unstructured, loud, chaotic and emotional. However, later on, Shakers developed precision dances and orderly rituals. The Shakers have also written thousands of religious songs.

The meetinghouses were painted white and unadorned, with shutters and carvings eschewed as worldly things. The prescribed uniform costume with woman's neckerchief and cap, and the custom of men wearing their hair long on the neck and cut in a straight bang on the forehead, still persist.

One of the major tendencies of the Shakers was to build, which resulted in a unique range of architecture, furniture and handicraft styles. Shakers designed their furniture with care, believing that making something well was in itself, "an act of prayer." They never fashioned items with elaborate details or extra decorations, but only made things for their intended uses. The ladder-back chair was a popular piece of furniture. Shaker craftsmen made most things out of pine or other inexpensive woods and hence their furniture was light in color and weight. Shaker interior spaces are characterized by an austerity and simplicity. For example, they had a continuous wooden device like a pelmet with hooks running all along the lintel level from which they hung the very light furniture pieces such as chairs when not in use. The simple, honest architecture of their homes, meeting houses, and barns have had a long-lasting influence on American architecture and design. They have a collection of furniture and utensils outside of Pittsfield, Mass., famous for their elegance and practicality.

Shaker music

The Shakers considered music to be an essential component of their religious experience. In Shaker society, a spiritual "gift" could also be a musical revelation, and they considered it to be important to record these musical inspirations as they occurred. Scribes, many of whom had no formal musical training, used a distinct form of music notation for this purpose involving letters of the alphabet, often not positioned on a staff, along with a simple notation of conventional rhythmic values. This method has a curious, and coincidental, similarity to some ancient Greek music notation.

Many of the lyrics to Shaker tunes consist of syllables and words from unknown tongues, the musical equivalent of glossolalia. Many of them were imitated from the sounds of Native American languages, as well as from the songs of African slaves, especially in the southernmost areas of the Shaker communities.

The most famed of Shaker songs is Simple Gifts, which Aaron Copland used as a theme for variations in Appalachian Spring. The tune was composed by Elder Joseph Brackett and originated in the Shaker community at Alfred, Maine in 1848. Many contemporary Christian denominations incorporate this tune into hymnals, under various names, including "Lord of the Dance," adapted by English poet and songwriter Sydney Carter.

The Shakers composed thousands of songs, and created many dances, which were an important part of the Shaker worship services.

Modern-day Shakers

Membership in the Shakers dwindled in the late 1800s for several reasons. People were attracted to cities and away from the farms. Shaker products could not compete with mass-produced products that became available at much lower cost. Shakers could not have children, and although they did adopt up until the states gained control of adoption homes, this was not a major source of new members. Some Shaker settlements, such as Pleasant Hill community in Kentucky, have become museums.

Believers have continually looked at the story of Ann Lee as a cornerstone of the theological architecture that has distinguished their church from other American religious groups. Shaker theology, its manifestation in material artifacts such as furniture and oval boxes, and the Ann Lee story have continually drawn the attention of outsiders either fascinated or repulsed by them.

Although there were six thousand believers at the peak of the Shaker movement, there were only twelve Shakers left by 1920. Shakers are no longer allowed to adopt orphan children after new laws were passed in 1960 refusing religious groups to take control of adoption, but adults who wish to embrace Shaker life are welcome. In the United States there were two remaining active Shaker communities, at Sabbathday Lake, Maine and Canterbury, New Hampshire, the latter of which died with its last member, Ethel Hudson, in September 1992.[2] The Sabbathday Lake community still accepts new recruits, as it has since its founding. This community, founded in 1783, was one of the smaller and more isolated Shaker communities during the sect's heyday. They farm and practice a variety of handicrafts. The village has been open to the public since 1931, when the Shaker Museum and Library was established. [3] Now Mother Ann day is celebrated on the first Sunday of August. The people sing and dance and a Mother Ann cake is presented. There is a legend that one of Mother Ann's predictions states that there will be a revival when there are only five Shakers left. However, there is no evidence to suggest Mother Ann stated this.

The modern day union of Shakers is known as the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Coming.

The daily schedule of a Shaker in Sabbathday Lake Village is as follows:

- The day will begin for many at 7:30 a.m., the Great Bell on Dwelling House rings calling every one to breakfast.

- At 8:00 a.m. Morning Prayers will start. They may read two Psalms and then read from the Bible. This will be followed by Prayer and silent prayer, concluded with the singing of a Shaker hymn.

- [Work for the Shakers begins at 8:30.

- Work is interrupted at 11:30 for Mid-day prayers.

- Dinner begins at 12:00. This is the main meal for the Shakers.

- Work will continue at 1:00 p.m.

- At 6:00 it is supper time, the last meal of the day.

- On Wednesdays at 5:00 p.m. they hold a prayer meeting which is followed by a Shakers Studies class.

Shaker Trust

To preserve their legacy as well as their idyllic, lakeside property at Sabbathday Lake, Maine, the Shakers announced in October 2005 that they had entered into a trust with the state of Maine and several conservation groups. Under the agreement, the Shakers will sell conservation easements to the trust, allowing the village to ward off development and continue operating as long as there are Shakers to live there.

The agreement does not specify whether the property will become a park, museum or other public space should the Shakers die off. That decision would be made by a nonprofit corporation—the United Society of Shakers, Sabbathday Lake Inc.—whose board members are largely non-Shakers. The $3.7 million conservation plan relies on grants, donations and public funds.

Influence

Shakers won respect and admiration for their productive farms and orderly communities. Their industry brought about many inventions like the screw propeller, Babbitt metal, the rotary harrow, the circular saw, the clothespin, the flat broom and the wheel-driven washing machine. They were once the largest producers of medicinal herbs in the United States, and pioneers in the sale of seeds in paper packets. Shaker dances and songs are a largely unrecognized aspect of folk art.

Shaker ways influenced many people to write books and adopt ways of life from Shakers. By the middle of the twentieth century, as the Shaker communities themselves were disappearing, some American collectors whose visual tastes were formed by the stark aspects of the modernist movement found themselves drawn to the spare artifacts of Shaker culture, in which "form follows function" was also clearly expressed. Kaare Klint, an architect and famous furniture designer, used styles from Shaker furniture in his work. Another example is Doris Humphrey, an innovator in technique, choreography, and theory of dance movement. She made a full theatrical art with her dance entitled "Dance of The Chosen Ones" in which the nature of the Shakers’ religious fervor was depicted.

Notes

- ↑ Stacey Chase. "The Last Ones Standing", The Boston Globe, July 23, 2006.

- ↑ New York Times article of September 12, 1992"Ethel Hudson, 96, Dies: One of the Last Shakers" Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ↑ Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village Shaker Museum, and Sunday services, Retrieved October 17, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andrews, Edward D. The People Called Shakers. Dover Publications, 1963. ISBN 0486210812

- Andrews, Edward Deming and Faith Andrews. Work and Worship Among the Shakers. Dover Publications, 1982. ISBN 0486243826

- Foster, Lawrence. "Shakers," in Mircea Eliade (ed.) Encyclopedia of Religion. MacMillian, 1987. Vol. 13, 200-201.

- Portman, Rob and Cheryl Bauer. Wisdom's Paradise: The Forgotten Shakers of Union Village. Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press, 2004. ISBN 1882203402

- Stein, Stephen J. The Shaker Experience in America: A History of the United Society of Believers. Yale University Press, 1994. ISBN 0300059337

External links

All links retrieved November 2, 2019.

- The Crooked Lake Review Fall, 2005, "Sodus Bay and Groveland: Shaker Life In Western New York"

- Shaker Heritage Society, Albany, NY

- UBU Ethnopoetry Gift Drawings & Gift Songs

- Shaker Museum and Library

- Sabbathday Lake ME Shaker Village

- Canterbury Village

- Hancock Village

- Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.