Samaria

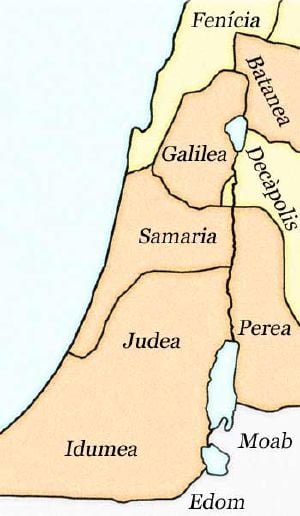

Samaria was the capital of the ancient Kingdom of Israel. It was also the name of the administrative district surrounding the city under later Greek and Roman administrations, referring to the mountainous region between the Sea of Galilee to the north and Judea to the south. The territory of Samaria was the central region of the biblical Land of Israel, today located in the northern West Bank.

Human habitation in Samaria dates back to the fourth millennium B.C.E., but the town was formally founded as Israel's capital by King Omri in the early ninth century B.C.E. It was the residence of the northern kingdom's most famous ruler, King Ahab, and his infamous queen, Jezebel. Many of the northern kings were entombed there. Between c. 884-722 B.C.E. Samaria endured several attacks and remained Israel's capital until it was captured by the Assyrian Empire and its leading residents were deported.

Samaria later became the central city of the Samaritan nation and lent its name to the surrounding administrative district in Greek and Roman times. It was rebuilt as Sebaste by Herod the Great in 27 B.C.E. In the New Testament, the territory of Samaria was where Jesus met the "woman at the well" to whom he revealed his identity as the Messiah. Samaria was also the origin of the traveler known as the "Good Samaritan" in one of Jesus' best-known parables. In the Book of Acts, the city of Samaria was the location of the first successful Christian evangelical effort outside of Jerusalem. It is also traditionally believed to be the burial place of John the Baptist.

In the twentieth century, the remains of Ahab or Omri's palace were discovered by archaeologists as were the later monumental steps of a major temple constructed by Herod the Great in Samaria.

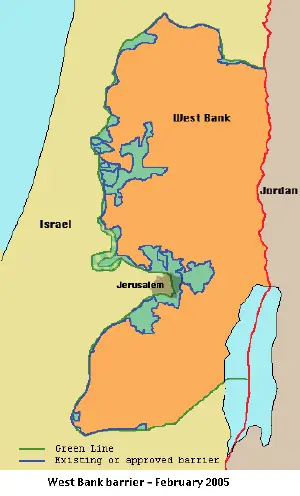

In modern times, the territory of Samaria came under British rule with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. It came under Jordanian control in 1948 but was seized by Israel during the Six Day War of 1967, and is currently under the administration of the Palestinian Authority. Israeli settlements in Samaria also have been established and are the subject of international controversy.

Location and climate

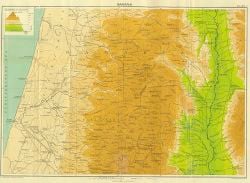

To the north, the territory of Samaria is bounded by the Esdraelon valley; to the east by the Jordan River; to the west by the Carmel Ridge (in the north) and the Sharon plain (in the west); to the south by Judea (the Jerusalem mountains). The Samarian hills are not very high, seldom reaching a height of over 800 meters. Samaria's climate is generally more hospitable than the climate of Judea. In ancient times, this combined with more direct access to Mediterranean trade routes to give the northern kingdom a substantial economic advantage over its southern neighbor.

Capital of ancient Israel

The city of Samaria, the ancient capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel, was built by King Omri in the seventh year of his reign, c. 884 B.C.E., on the mountain he had reportedly bought for two talents of silver from a man called Shemer, after whom the city was named (1 Kings 16:23-24). [1] It was situated six miles from Shechem and was noted both for its strategic location and the fertility of the surrounding lands. Modern excavations reveal human occupation there dating back to the fourth millennium B.C.E. The site was a center of an extensive wine and oil production area.

Omri faced military pressure from the kingdom of Syria (Aram), and was forced for a time to allow Syrian merchants to open markets in the streets of Samaria (1 Kings 29:34). However, it remained the capital of Israel for more than 150 years, constituting most of the northern kingdom's history, until it was captured by the Assyrians in 722-721 B.C.E. The city was strongly fortified and endured several sieges before its downfall. Archaeologists believe the city of Samaria was richer and more developed than any other city in Israel or Judah.

Omri's son, King Ahab, reportedly built an "ivory palace" in the capital (1 Kings 16:39). The remains of an impressive Iron Age building at the site were excavated in the twentieth century, and in recent years, archaeologists may have discovered royal tombs possibly belonging to the Omride dynasty. A valuable collection of ivory carvings was also unearthed.

The city gate of Samaria is mentioned several times in the Books of Kings and Chronicles, and there is also a reference to "the pool of Samaria" in 1 Kings 22:38. Ahab also reportedly constructed a temple to Baal at Samaria, probably at the behest of his Phoenician wife Jezebel, much to the dismay of the prophets Elijah and Elisha. During the time of Ahab, the city successfully endured two sieges by the Syrians under Ben-hadad II. At Samaria's famous gate, Ahab met his ally and son-in-law, Jehoshaphat of Judah, to hear the dramatic words of the prophet Micaiah (1 Kings 22:10). During the reign of Ahab's son Joram, (2 Kings 6-7) the Syrian siege of Samaria was so intense that some residents were reduced to cannibalism, but the city was rescued by God's miraculous intervention.

The prophet Elisha, however, recruited one of the nation's military commanders, Jehu, to seize the throne from Joram and slaughter Ahab's descendants, execute Jezebel, and destroy Samaria's temple of Baal together with all of its priests. Some 70 of Ahab's sons were slain at Samaria on Jehu's orders.

When Jehu's grandson Joash (also called Jehoash—c. 801–786 B.C.E.) warred against Judah and captured Jerusalem, he brought to Samaria the gold, silver, and vessels of the Temple and the king's palace (2 Kings 14:14). Later, King Pekah (c. 737–732) returned victoriously to Samaria with a great number of captives of Judah. However, upon his arrival in the capital, the intervention of the prophet Oded resulted in these captives being released (2 Chron. 27: 8-9, 15). Under Jeroboam II, Samaria was famous both for its prosperity and its corruption.

In the biblical tradition, Samaria was a place of idolatry and corruption, although it is also clear that several of its kings, including even the wicked Ahab, honored Yahweh. The city's moral corruption was denounced by Amos, Isaiah, Micah, and other prophets, who also foretold the downfall of the city as a punishment for its sins.[2]

Although Samaria had successfully withstood the Syrians, and sometimes allied with them against Judah, the rise of the Assyrian Empire would eventually spell its doom. In the seventh year of King Hoshea, Samaria was besieged by Shalmaneser. Three years later it was captured by an Assyrian king (2 Kings 17-18), whose name is not mentioned. Josephus ("Ant." ix. 14, § 1) states that it was Shalmaneser, but Assyrian inscriptions show that it was Sargon II, who ascended the throne in 722 B.C.E., and had captured Samaria by the following year.

The city, however, was not destroyed (Jer. 41:5). According to Sargon's inscriptions, two years later it made an alliance with the cities of Hamath, Arpad, and Damascus against the Assyrians. This resistance failed when Sargon overthrew the King of Hamath, which he apparently boasts of in 2 Kings 18:32-35. The elite class of citizens from Samaria and other northern towns were replaced by colonists from different countries, sent there by the Assyrian king.

The new settlers, probably influenced by the remaining local population, came to believe that the "God of the land" had not been properly propitiated, and thus priests of Yahweh were sent back by the Assyrian authorities to teach the settlers to worship the Israelite God (2 Kings 17:24-41). These Assyrian settlers intermarried with native Israelites and, according to Jewish sources, were the founders of the Samaritan religion, as well as being the ancestors of the Samaritans. The Samaritans themselves, however, claim that they worshiped Yahweh from the time of Moses onward, at Mount Gerezim, near Shechem. They denounce the Jewish claim of Jerusalem being the only authorized shrine of Yahweh as a fraud perpetrated by the priest Eli and his successors.

Under Greek and Roman rule

Samaria emerged again into history four centuries after its capture by the Assyrians. By this time Samaria was once again an important city, with its Samaritan Temple at Gerizim rivaling or exceeding the competing Yahwist Temple of Jerusalem, which had been rebuilt after the Jews of Judah to returned from Babylonian exile. The Samaritans, having assassinated the Greek governor of Syria in 332 or 331 B.C.E., were severely punished by Alexander the Great. Alexander sent his own people, the Macedonians, to control the city (Eusebius, "Chronicon"). A few years later, Alexander had Samaria rebuilt. The Samaritans, however, were not easily controlled. In 312, the city was dismantled by Ptolemy, son of Lagus, and 15 years later it was again captured and demolished, by Demetrius Poliorcetes.

Almost two centuries elapsed during which nothing is heard of Samaria, but it is evident that the city was again rebuilt and strongly fortified. At the end of the second century B.C.E., the Jewish ruler John Hyrcanus besieged it for an entire year before he captured and destroyed it, along with the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim, probably in or shortly before 107 B.C.E. (Josephus, l.c. xiii. 10). Samaria was later held by Alexander Jannæus ("Ant." xiii. 15, § 4), and was afterward taken by Pompey, who rebuilt it and attached it to the government of Syria (ib. xiv. 4, § 4). The city was further strengthened by Gabinius.

Caesar Augustus entrusted Samaria to Herod the Great, under whom it flourished anew as Sebaste. Herod rebuilt it in 27 B.C.E. on a much larger scale and embellished it with magnificent buildings, including the new Temple of Augustus. In the same year he married the beautiful Samaritan princess Malthace, to whom two of his heirs were born. Under Herod the city became the capital of the Roman administrative district of Samaria, which was one of the subdivisions of the Roman province of Syria Iudaea, the other two being Judea and Galilee.

The New Testament contains several references to Samaria. In Matthew 10:5, Jesus instructs his disciples: "Do not... enter any town of the Samaritans." However, Luke's Gospel displays a different attitude in its famous parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10). The district of Samaria is further mentioned in Luke 17:11-20, in the miraculous healing of the ten lepers, which took place on the border of Samaria and Galilee. John 4:1-26 records Jesus' encounter in Samarian territory at Jacob's well with the Samaritan woman of Sychar, in which Jesus declares himself to be the Messiah. In Acts 8:5-14, it is recorded that Philip went to the city of Samaria and preached there, converting many residents, including the famous local miracle-worker Simon, called "Simon Magus" in Christian tradition.

Sebaste is mentioned in the Mishnah ('Ar. iii. 2), where its orchards are praised. After Herod's death, Sebaste and the province of Samaria came under the administration of his son Archelaus, after whose banishment it passed to the control of Roman procurators. It then came under Herod Agrippa I, and later again came under the procurators ("Ant." xvii. 11, § 4). At the outbreak of the Jewish war in 66 C.E. it was attacked by the Jewish forces ("B. J." ii. 18, § 1). Josephus ("B. J." ii. 3, § 4) also speaks of the Jewish soldiers of Sebaste who had served in Herod's army and later sided with the Romans when the Jews revolted. In the aftermath of the Bar Kochba revolt of the second century C.E., Hadrian consolidated the older political units of Judea, Galilee, and Samaria into the new province of Syria Palaestina (Palestine).

Under Emperor Septimius Severus at the end of the second century, Sebaste became a Roman colony, but with the growth of nearby Nablus it lost its importance. In the fourth century Sebaste was a small town (Eusebius, "Onomasticon," s.v.). Saint Jerome (Commentary on Obadiah) records the tradition that Samaria was the burial-place of Elisha, Obadiah, and John the Baptist.

Modern history

The history of Samaria in modern times begins when the territory of Samaria, formerly belonging to the Ottoman Empire, came under the administration of the United Kingdom in the aftermath of World War I by mandate of the League of Nations. After the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the territory came under the control of Jordan.

Samaria was taken from Jordan by Israeli forces during the 1967 Six-Day War. Jordan withdrew its claim to the West Bank, including Samaria, only in 1988, as was later confirmed by the Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty of 1993. Jordan now recognizes the Palestinian Authority as sovereign in the territory. In the 1994 Oslo accords, responsibility for the administration over some of the territory of Samaria was transferred to the Palestinian Authority.

Israel has been criticized for the policy of establishing settlements in Samaria. The area's borders are disputed and Israel's position is that the legal status of the land is unclear.

Excavations

The acropolis of Samaria has been extensively excavated down to the bedrock, the most significant find being the Palace of Omri and/or Ahab. The Omride palace was located on an elevated four meter high rock-cut platform that isolated it from its immediate surroundings. While immediately below the palace, cut into the face of the bedrock platform, there are two rock-cut tomb chambers that have only recently been recognized and attributed to the kings of Israel. West of the palace there are meager remains of other buildings from this period.

The acropolis area was extended in all directions by the addition of a massive perimeter wall built in the casemate style, and the new enlarged rectangular acropolis measured c. 290 ft. (90 m.) from north to south and at least c. 585 ft. (180 m.) from west to east. Massive stone stairs have also been uncovered, believed to have been constructed by Herod the Great as the entry to the temple he dedicated to Augustus at Sebaste.

A large rock-cut pool near the northern casemate wall was initially identified with the biblical "Pool of Samaria." It is now thought to be a grape-treading area that originated before the Omride dynasty but was also used in later years. North of the palace, a rich cache of Phoenician ivory furniture ornamentations were retrieved, which may be related to the supposed "Ivory Palace" that Ahab built (1 Kings 22:39).

Notes

- ↑ However, the etymology of the name may also be "watch mountain."

- ↑ It should be noted that the prophets also criticized Jerusalem and denounced many of Judah's kings for much the same reasons. A particular bone of contention for the biblical writers was the fact that the northern kings supported the Yahwist shrines at Dan and Bethel at pilgrimage sites, competing with the southern Temple of Jerusalem. In later centuries, the Samaritan temple dedicated to Yahweh at Gerizim would be destroyed by the Jewish ruler John Hyrcanus.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Albright, William F. Archeology of Palestine. Peter Smith Pub. Inc., 2nd edition, 1985. ISBN 0844600032

- Becking, Bob. The Fall of Samaria: An Historical and Archaeological Study. Brill Academic Publishers, 1992. ISBN 9004096337

- Bright, John. A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press; 4th edition, 2000. ISBN 0664220681

- Grant, Michael. The History of Ancient Israel. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1984. ISBN 0684180812

- Keller, Werner. The Bible as History. Bantam; 2nd Rev edition, 1983. ISBN 0553279432

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X

- Tappy, Ron E. The Archeology of Israelite Samaria, Volume 1: Early Iron Age Through the Ninth Century B.C.E. Harvard Semitic Studies 44. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992. ISBN 978-1555407704

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Samaria Jewish Encyclopedia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.