Difference between revisions of "Rubella" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) (added claimed tag) |

|||

| (16 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} |

| − | {{ | + | {{Infobox_Disease |

| − | + | | Name = Rubella | |

| − | ICD10 | + | | Image = |

| − | + | | Caption = | |

| − | + | | DiseasesDB = 11719 | |

| − | + | | ICD10 = {{ICD10|B|06||b|00}} | |

| − | + | | ICD9 = {{ICD9|056}} | |

| + | | ICDO = | ||

| + | | OMIM = | ||

| + | | MedlinePlus = 001574 | ||

| + | | eMedicineSubj = emerg | ||

| + | | eMedicineTopic = 388 | ||

| + | | eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|peds|2025}} {{eMedicine2|derm|259}} | ||

| + | | MeshID = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | |||

{{Taxobox | color=violet | {{Taxobox | color=violet | ||

| name = ''Rubella virus'' | | name = ''Rubella virus'' | ||

| Line 17: | Line 25: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | '''Rubella''', commonly known as '''German measles''' and also called '''three-day measles''', is a highly contagious [[virus|viral]] [[disease]] caused by the '''''rubella virus''''' ''(Rubivirus)''. Symptoms are typically mild and an attack can pass unnoticed. However, it can have severe complications when contracted by pregnant women in the first trimester of [[pregnancy]], with infection of the [[fetus]] commonly leading to death of the fetus or birth defects. When occurring early in pregnancy, the fetus faces a risk of infection as high as ninety percent (Breslow 2002), with birth defects ensuing in fifty percent of the cases where the mother contracts rubella during the first month of pregnancy (Longe 2006). | ||

| + | Rubella was once a common childhood disease, but there is now a highly effective [[vaccine]]. Following primary infection, there is usually lifelong protective immunity from further episodes of rubella. | ||

| − | + | As uncomfortable as rubella is for the sufferer, there was a time that it was not uncommon for mothers to deliberately expose their young children, and particularly the daughters, to rubella. This is because of the lifetime immunity conferred and the potential complications should a pregnant women get rubella, combined with the view that it is better to go through limited suffering for the sake of future benefit. Today, some practitioners of alternative medicine continue to advocate this natural route rather than use of a vaccine, although with the presence of a vaccine it is difficult to find those from whom to contract the disease (Longe 2005). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Overview== | |

| − | + | Rubella normally is a mild disease, and one in which humans are the only known natural host (Breslow 2002). It is spread through the fluid droplets expelled from an infected person's nose or mouth (Longe 2006). The rubella virus has an incubation period of 12 to 23 days and an infected person is contagious for about seven days before the symptoms appear and for about four days after appearance of the symptoms (Longe 2006). However, from 20 to 50 percent of those infected do not demonstrate symptoms (Breslow 2002). | |

| − | + | This disease once was quite common in childhood, although individuals of any age could become infected if not previously infected or vaccinated. In 1969, a vaccine became available, and in the 20 years since its introduction, reported rubella cases dropped 99.6 percent, with only 229 cases reported in the [[United States]] in 1996 (Longe 2006). | |

| − | + | Both immunization and infection with the disease generally confers lifetime immunity. [[Antibody|Antibodies]] developed against the [[virus]] as the rash fades are maintained for life and are effective against the virus since there is only one [[antigen]] viral form. | |

| − | + | While normally there are few severe complications, women who are in their first three months of pregnancy and contract the disease have a risk of miscarriage and there is risk to the child of severe genetic defects. This is because rubella can also be transmitted from a mother to her developing baby through the bloodstream via the [[placenta]]. The birth defects, known as congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), include [[cataracts]], hearing impairment, [[heart]] defects, [[glaucoma]], and mental retardation (Longe 2006; Breslow 2002). The risk to the fetus being infected may be as much as ninety percent (Breslow 2002), with birth defects occurring in fifty percent of women who are infected in the first month of pregnancy, twenty percent in the second month, and ten percent in the third month (Longe 2006). | |

| + | ==History== | ||

| + | [[Friedrich Hoffmann]] made a clinical description of rubella in 1740 (Ackerknecht 1982). Later descriptions by de Bergen in 1752 and Orlow in 1758 supported the belief that this was a derivative of [[measles]]. In 1814, George de Maton first suggested that it be considered a disease distinct from both measles and [[scarlet fever]]. All these physicians were German, and the disease was known medically as Rötheln (from the German name ''Röteln''), hence the common name of "German measles" (Ackerknecht 1982; Lee and Bowden 2000; Atkinson et al. 2007). | ||

| − | + | English Royal Artillery surgeon, Henry Veale, observed an outbreak in [[India]]. He coined the euphonious name "rubella" (from the [[Latin]], meaning "little red") in 1866 (MOHNZ 2006). It was formally recognized as an individual entity in 1881, at the International Congress of Medicine in London (PAHO 1998). In 1914, Alfred Fabian Hess theorized that rubella was caused by a virus, based on work with [[monkey]]s (Hess 1914). In 1938, Hiro and Tosaka confirmed this by passing the disease to children using filtered nasal washings from acute cases (Atkinson et al. 2007). | |

| − | + | In 1940, there was a widespread epidemic of rubella in [[Australia]]. Subsequently, opthalmologist Norman McAllister Gregg found 78 cases of congenital cataracts in infants and 68 of them were born to mothers who had caught rubella in early pregnancy (Lee and Bowden 2000; Atkinson et al. 2007). Gregg published an account, ''Congenital Cataract Following German Measles in the Mother'', in 1941. He described a variety of problems now know as [[congenital rubella syndrome]] (CRS) and noticed that the earlier the mother was infected, the worse the damage was (PAHO 1998). The virus was isolated in tissue culture in 1962 by two separate groups led by physicians Parkman and Weller (Lee and Bowden 2000; MOHNZ 2006). | |

| − | + | There was a pandemic of rubella between 1962 and 1965, starting in [[Europe]] and spreading to the [[United States]] (MOHNZ 2006). In the years 1964-65, the United States had an estimated 12.5 million rubella cases. This led to 11,000 miscarriages or therapeutic abortions and 20,000 cases of congenital rubella syndrome. Of these, 2,100 died as neonates, 12,000 were deaf, 3,580 were blind, and 1,800 were mentally retarded. In New York alone, CRS affected one percent of all births (PAHO 1998). | |

| − | + | In 1969, a live attenuated virus vaccine was licensed (Atkinson et al. 2007). In the early 1970s, a triple vaccine containing attenuated measles, mumps, and rubella ([[MMR vaccine|MMR]]) viruses was introduced (MOHNZ 2006). | |

| − | + | ==Symptoms== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Although symptoms are not always present, and in fact missing in an estimated twenty to fifty percent of infections, the first visible sign is usually a fne red rash that begins on the face and moves downward to cover the entire body within 24 hours (Breslow 2002). There may also be a low [[fever]], joint pain and swelling, and swollen glands (Breslow 2002). The fever rarely rises above 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit). The rash appears as pink dots under the skin. It appears on the first or third day of the illness but it disappears after a few days with no staining or peeling of the skin. In about 20 percent of the cases there is [[Forchheimer's sign]], characterized by small, red [[papule]]s on the area of the [[soft palate]]. There may be flaking, dry skin as well. | ||

| + | Symptoms typically disappear within three or four days, although joint pain may continue for a week or two (Breslow 2002). | ||

| − | == | + | ==Prevention and treatment== |

| + | Until the disease has run its course, symptoms are usually treated with [[paracetamol]], which acts an an analgesic (pair reliever) and antipyretic (fever reducer). | ||

| − | + | Fewer cases of rubella have occurred ever since a [[vaccine]] became available in 1969, which is usually presented in combination against measles and mumps as well and is known as the MMR vaccine. In most Western countries, the vast majority of people are vaccinated against rubella as children at 12 to 15 months of age. A second dose is required before age 11. The vaccine may give lifelong protection against rubella. A side-effect of the vaccine can be transient [[arthritis]]. | |

| − | + | The [[Immunization (medicine)|immunization]] program has been quite successful with [[Cuba]] declaring the disease eradicated in the 1990s and the [[United States]] eradicating it in 2005 (Pallarito 2005). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Some alternative practitioners recommend, rather than vaccinating a healthy child, allowing the child to naturally contract the disease at the age of five or six years, since the symptoms are mild and the immunity naturally lasts a lifetime (Longe 2005). While this used to be common practice, the presence of vaccines in the developed world makes it difficult to find someone from whom to contract the disease. | ||

| + | Alternative treatments vary. Ayurvedic practitioners recommend giving ginger or close tea to hasten the progress of the disease, and traditional Chinese medicine prescribe herbs such as peppermint ''(Mentha piperita)'' and chai hu ''(Bupleurum chinense)'' (Longe 2005). Witch hazel ''(Hamamelis virginiana)'' is used in the West to alleviate rubella symptoms and an eyewash made of eyebright ''(Euphrasia officinalis)'' to relieve eye discomfort (Longe 2005). | ||

| + | == References == | ||

| + | * Ackerknecht, E. H. 1982. ''A short history of medicine''. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801827264. | ||

| + | * Atkinson, W., J. Hamborsky, L. McIntyre, and S. Wolfe, eds. 2007. [http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/pink-chapters.htm Chapter 12; Rubella] In ''Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, 10th ed''. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 11, 2007. | ||

| + | * Breslow, L. 2002. ''Encyclopedia of Public Health''. New York: Macmillan Reference USA/Gale Group Thomson Learning. | ||

| + | * Fabian, H. 1914. German measles (rubella): An experimental study. ''The Archives of Internal Medicine'' 13: 913-916. As cited by O. D. Enersen. 2007. [http://www.whonamedit.com/doctor.cfm/2283.html Alfred Fabian Hess] ''Whonamedit''. Retrieved December 11, 2007. | ||

| + | * Lee, J. Y., and D. S. Bowden. 2000. [http://cmr.asm.org/cgi/content/full/13/4/571 Rubella virus replication and links to teratogenicity] ''Clin. Microbiol. Rev.'' 13(4): 571-587. PMID 11023958 Retrieved December 11, 2007. | ||

| + | * Longe, J. L. 2006. ''The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine.'' Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414403682. | ||

| + | * Longe, J. L. 2005. ''The Gale Encyclopedia of Cancer: A Guide to Cancer and Its Treatments''. Detroit: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 1414403623. | ||

| + | * Ministry of Health, New Zealand (MOHNZ). 2006. [http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/4617/$File/2006-11rubella.pdf Chapter 11: Rubella] ''[http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/immunisation-handbook-2006 Immunisation Handbook''] Retrieved December 11, 2007. | ||

| + | * Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). 1998. [http://www.ops-oms.org/english/ad/fch/im/nlrubella_PublicHealthBurdenRubellaCRS_Aug1998.pdf Public health burden of rubella and CRS]. ''EPI Newsletter'' Volume XX, Number 4. Retrieved September 9, 2007. | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Life sciences]][[Category:Health and disease]][[Category:Diseases]] | |

| − | [[Category:Life sciences]] | + | {{credit|Rubella|156602583}} |

| − | {{credit| | ||

Latest revision as of 19:46, 20 August 2022

| Rubella Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | B06 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 056 |

| DiseasesDB | 11719 |

| MedlinePlus | 001574 |

| eMedicine | emerg/388 peds/2025 derm/259 |

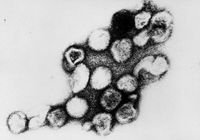

| Rubella virus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Virus classification | ||||||||

|

Rubella, commonly known as German measles and also called three-day measles, is a highly contagious viral disease caused by the rubella virus (Rubivirus). Symptoms are typically mild and an attack can pass unnoticed. However, it can have severe complications when contracted by pregnant women in the first trimester of pregnancy, with infection of the fetus commonly leading to death of the fetus or birth defects. When occurring early in pregnancy, the fetus faces a risk of infection as high as ninety percent (Breslow 2002), with birth defects ensuing in fifty percent of the cases where the mother contracts rubella during the first month of pregnancy (Longe 2006).

Rubella was once a common childhood disease, but there is now a highly effective vaccine. Following primary infection, there is usually lifelong protective immunity from further episodes of rubella.

As uncomfortable as rubella is for the sufferer, there was a time that it was not uncommon for mothers to deliberately expose their young children, and particularly the daughters, to rubella. This is because of the lifetime immunity conferred and the potential complications should a pregnant women get rubella, combined with the view that it is better to go through limited suffering for the sake of future benefit. Today, some practitioners of alternative medicine continue to advocate this natural route rather than use of a vaccine, although with the presence of a vaccine it is difficult to find those from whom to contract the disease (Longe 2005).

Overview

Rubella normally is a mild disease, and one in which humans are the only known natural host (Breslow 2002). It is spread through the fluid droplets expelled from an infected person's nose or mouth (Longe 2006). The rubella virus has an incubation period of 12 to 23 days and an infected person is contagious for about seven days before the symptoms appear and for about four days after appearance of the symptoms (Longe 2006). However, from 20 to 50 percent of those infected do not demonstrate symptoms (Breslow 2002).

This disease once was quite common in childhood, although individuals of any age could become infected if not previously infected or vaccinated. In 1969, a vaccine became available, and in the 20 years since its introduction, reported rubella cases dropped 99.6 percent, with only 229 cases reported in the United States in 1996 (Longe 2006).

Both immunization and infection with the disease generally confers lifetime immunity. Antibodies developed against the virus as the rash fades are maintained for life and are effective against the virus since there is only one antigen viral form.

While normally there are few severe complications, women who are in their first three months of pregnancy and contract the disease have a risk of miscarriage and there is risk to the child of severe genetic defects. This is because rubella can also be transmitted from a mother to her developing baby through the bloodstream via the placenta. The birth defects, known as congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), include cataracts, hearing impairment, heart defects, glaucoma, and mental retardation (Longe 2006; Breslow 2002). The risk to the fetus being infected may be as much as ninety percent (Breslow 2002), with birth defects occurring in fifty percent of women who are infected in the first month of pregnancy, twenty percent in the second month, and ten percent in the third month (Longe 2006).

History

Friedrich Hoffmann made a clinical description of rubella in 1740 (Ackerknecht 1982). Later descriptions by de Bergen in 1752 and Orlow in 1758 supported the belief that this was a derivative of measles. In 1814, George de Maton first suggested that it be considered a disease distinct from both measles and scarlet fever. All these physicians were German, and the disease was known medically as Rötheln (from the German name Röteln), hence the common name of "German measles" (Ackerknecht 1982; Lee and Bowden 2000; Atkinson et al. 2007).

English Royal Artillery surgeon, Henry Veale, observed an outbreak in India. He coined the euphonious name "rubella" (from the Latin, meaning "little red") in 1866 (MOHNZ 2006). It was formally recognized as an individual entity in 1881, at the International Congress of Medicine in London (PAHO 1998). In 1914, Alfred Fabian Hess theorized that rubella was caused by a virus, based on work with monkeys (Hess 1914). In 1938, Hiro and Tosaka confirmed this by passing the disease to children using filtered nasal washings from acute cases (Atkinson et al. 2007).

In 1940, there was a widespread epidemic of rubella in Australia. Subsequently, opthalmologist Norman McAllister Gregg found 78 cases of congenital cataracts in infants and 68 of them were born to mothers who had caught rubella in early pregnancy (Lee and Bowden 2000; Atkinson et al. 2007). Gregg published an account, Congenital Cataract Following German Measles in the Mother, in 1941. He described a variety of problems now know as congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) and noticed that the earlier the mother was infected, the worse the damage was (PAHO 1998). The virus was isolated in tissue culture in 1962 by two separate groups led by physicians Parkman and Weller (Lee and Bowden 2000; MOHNZ 2006).

There was a pandemic of rubella between 1962 and 1965, starting in Europe and spreading to the United States (MOHNZ 2006). In the years 1964-65, the United States had an estimated 12.5 million rubella cases. This led to 11,000 miscarriages or therapeutic abortions and 20,000 cases of congenital rubella syndrome. Of these, 2,100 died as neonates, 12,000 were deaf, 3,580 were blind, and 1,800 were mentally retarded. In New York alone, CRS affected one percent of all births (PAHO 1998).

In 1969, a live attenuated virus vaccine was licensed (Atkinson et al. 2007). In the early 1970s, a triple vaccine containing attenuated measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) viruses was introduced (MOHNZ 2006).

Symptoms

Although symptoms are not always present, and in fact missing in an estimated twenty to fifty percent of infections, the first visible sign is usually a fne red rash that begins on the face and moves downward to cover the entire body within 24 hours (Breslow 2002). There may also be a low fever, joint pain and swelling, and swollen glands (Breslow 2002). The fever rarely rises above 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit). The rash appears as pink dots under the skin. It appears on the first or third day of the illness but it disappears after a few days with no staining or peeling of the skin. In about 20 percent of the cases there is Forchheimer's sign, characterized by small, red papules on the area of the soft palate. There may be flaking, dry skin as well.

Symptoms typically disappear within three or four days, although joint pain may continue for a week or two (Breslow 2002).

Prevention and treatment

Until the disease has run its course, symptoms are usually treated with paracetamol, which acts an an analgesic (pair reliever) and antipyretic (fever reducer).

Fewer cases of rubella have occurred ever since a vaccine became available in 1969, which is usually presented in combination against measles and mumps as well and is known as the MMR vaccine. In most Western countries, the vast majority of people are vaccinated against rubella as children at 12 to 15 months of age. A second dose is required before age 11. The vaccine may give lifelong protection against rubella. A side-effect of the vaccine can be transient arthritis.

The immunization program has been quite successful with Cuba declaring the disease eradicated in the 1990s and the United States eradicating it in 2005 (Pallarito 2005).

Some alternative practitioners recommend, rather than vaccinating a healthy child, allowing the child to naturally contract the disease at the age of five or six years, since the symptoms are mild and the immunity naturally lasts a lifetime (Longe 2005). While this used to be common practice, the presence of vaccines in the developed world makes it difficult to find someone from whom to contract the disease.

Alternative treatments vary. Ayurvedic practitioners recommend giving ginger or close tea to hasten the progress of the disease, and traditional Chinese medicine prescribe herbs such as peppermint (Mentha piperita) and chai hu (Bupleurum chinense) (Longe 2005). Witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) is used in the West to alleviate rubella symptoms and an eyewash made of eyebright (Euphrasia officinalis) to relieve eye discomfort (Longe 2005).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ackerknecht, E. H. 1982. A short history of medicine. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801827264.

- Atkinson, W., J. Hamborsky, L. McIntyre, and S. Wolfe, eds. 2007. Chapter 12; Rubella In Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, 10th ed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- Breslow, L. 2002. Encyclopedia of Public Health. New York: Macmillan Reference USA/Gale Group Thomson Learning.

- Fabian, H. 1914. German measles (rubella): An experimental study. The Archives of Internal Medicine 13: 913-916. As cited by O. D. Enersen. 2007. Alfred Fabian Hess Whonamedit. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- Lee, J. Y., and D. S. Bowden. 2000. Rubella virus replication and links to teratogenicity Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13(4): 571-587. PMID 11023958 Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- Longe, J. L. 2006. The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414403682.

- Longe, J. L. 2005. The Gale Encyclopedia of Cancer: A Guide to Cancer and Its Treatments. Detroit: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 1414403623.

- Ministry of Health, New Zealand (MOHNZ). 2006. Chapter 11: Rubella Immunisation Handbook Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). 1998. Public health burden of rubella and CRS. EPI Newsletter Volume XX, Number 4. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.