Filmer, Robert

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) (import from wiki) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | [[ | + | {{epname|Filmer, Robert}} |

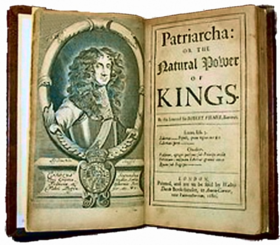

| − | Sir '''Robert Filmer''' ([[ | + | [[Image:Patriarcha-Book of-Robert Filmer Originally from 1680.png|thumbnail|280px|right|Filmer, Robert:''Patriarcha'', London, 1680]] |

| + | Sir '''Robert Filmer''' (1588 – May 26, 1653) was an [[England|English]] political theorist and one of the first [[absolutism|absolutists]]. Born into an aristocratic family and knighted at the beginning of the reign of Charles I, he was a staunch supporter of the king when civil war broke out in 1642. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Filmer developed a political theory, based on [[natural law]], which equated the authority of the king over his subjects with the authority of a father over his family. He used an argument based on the Book of [[Genesis]] to support the position that every king had inherited his [[patriarchy]] from [[Adam]], and was therefore divinely ordained. The Parliament could only advise the king, who alone made laws, which proceeded purely from his will. The king himself was not bound by any law, because by nature it was impossible that a man should impose a law on himself. Filmer rejected the [[democracy|democratic]] ideal that all people were born free and equal, arguing that everyone was born subordinate to a father. | ||

| − | + | ==Life== | |

| + | Sir Robert Filmer was born at East Sutton, in Kent, in 1588, the eldest son of Sir Edward Filmer. Robert was the eldest of eighteen children. | ||

| + | He matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1604. His friends included the High Church cleric, Peter Heylyn (1600-62), a great supporter of Archbishop William Laud. Knighted by Charles I at the beginning of his reign, he was an ardent supporter of the king's cause, and had a brother and son at court. In 1629, he inherited his father’s estates. | ||

| − | Filmer was | + | When civil war broke out in 1642, Filmer was too old to fight, but was a staunch Royalist. He was briefly imprisoned by Parliament, and his house in East Sutton is said to have been plundered by the parliamentarians ten times. He died May 26, 1653, in East Sutton, and is buried in the church there, surrounded by his descendants to the tenth generation, who were made baronets in his honor. |

| − | [[ | + | ==Background: The English Civil War== |

| − | + | The [[English Civil War]] consisted of a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians (known as [[Roundheads]]) and Royalists (known as [[Cavaliers]]) between 1642 and 1651. Previous civil wars had been about succession to the throne; this conflict concerned the manner in which England was to be governed. Until the time of Charles I, the British Parliament served largely as an advisory council to the king and consisted of aristocrats and landed gentry who were responsible for collecting taxes for the throne. Charles I antagonized Parliament and aroused their suspicions. Upholding the [[Divine Right of Kings]], he insisted that all his orders be obeyed without question. Against the wishes of Parliament, he sent a failed expedition to aid the [[Huguenots]] in [[France]] during the [[Thirty Years War]], and dissolved Parliament when they disapproved. Early in his reign he married a French [[Roman Catholicism|Catholic]] princess, arousing fears that his heirs would be Catholic. With the help of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, he began imposing High Anglican religious reforms on the Church of England, resulting in a rebellion in Scotland, which led to war. A series of three conflicts ended with a Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651. | |

| + | |||

| + | The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of his son Charles II, and the replacement of the English monarchy with first the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653) and then with a Protectorate (1653–1659), under the personal rule of [[Oliver Cromwell]]. It established a precedent that British monarchs could not govern without the consent of Parliament. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Works== | ||

| + | Filmer was already middle-aged when the great controversy between the king and the Commons roused him into literary activity. His writings offer an example of the doctrines held by the most extreme section of the Divine Right party. ''Anarchy of a Limited and Mixed Monarchy,'' an attack upon a treatise on monarchy by [[Philip Hunton]] (1604-1682), who maintained that the king's prerogative is not superior to the authority of the houses of parliament, was published in 1648. Another pamphlet entitled ''The Power of Kings,'' was written in 1648, but not published until 1680, and his ''Observations concerning the Original of Government upon Mr Hobbes's Leviathan, Mr Milton against Salmasius, and H. Grotius' De jure belli ac pacis,'' appeared in 1652. During the exclusion crisis of 1679–80 Filmer's political tracts were reissued (1679), and his major work, ''Patriarcha,'' was published as Tory propaganda. It had been written around 1628, long before the Civil Wars and before [[Thomas Hobbes]]’ ''De Cive'' and ''Elements of Law'' were published in 1647, making Filmer England’s first absolutist. Much of ''Patriarcha'' was directed against Cardinal Robert Bellarmine and [[Francisco Suárez]], who had criticized the Oath of Allegiance, a loyalty oath demanded of English Catholics in the wake of the [[Gunpowder Plot]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Political theory== | ||

| + | Filmer's political theory was based on [[natural law]]. He believed that the institutions of [[family]] and the state were established to fulfill the purpose of human nature, and that the government of a family by the father was the true original and model of all government. In the beginning of the world, God gave authority to [[Adam]], who had complete control over his descendants, even as to life and death. From Adam this authority was inherited by [[Noah]]; and Filmer quoted as not unlikely the tradition that Noah sailed up the [[Mediterranean]] and allotted the three continents of the Old World to the rule of his three sons. From [[Shem]], [[Ham]], and [[Japheth]] the [[patriarchy|patriarchs]] inherited the absolute power which they exercised over their families and servants; and from the patriarchs all kings and governors (whether a single monarch or a governing assembly) derive their authority, which is therefore absolute, and founded upon divine right. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The difficulty that a man by the secret will of God may unjustly attain to power which he has not inherited appeared to Filmer in no way to alter the nature of the power so obtained, for there is, and always shall be continued to the end of the world, a [[natural rights|natural right]] of a supreme father over every multitude. The king was perfectly free from all human control. He could not be bound by the acts of his predecessors, for which he was not responsible; nor by his own, for it was impossible in nature that a man should impose a law on himself; the law must be imposed by someone other than the person bound by it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Regarding the English constitution, he asserted, in his ''Freeholders Grand Inquest touching our Sovereign Lord the King and his Parliament'' (1648), that the Lords only give counsel to the king, the Commons only perform and consent to the ordinances of parliament, and the king alone is the maker of laws, which proceed purely from his will. He considered it monstrous that the people should judge or depose their king, for they would then be judges in their own cause. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Criticism of contract theorists== | ||

| + | Filmer criticized [[contract theory]] for suggesting that [[democracy]] was the natural form of government instituted by God, when almost everyone agreed that democracy was little better than mob rule. Filmer also pointed out that “rule by the people" was a highly ambiguous term. If the term “the people” included women and children, why were they in fact excluded from political affairs? If it did not include women and children, why not? Saying that women and children were subordinate to husbands and fathers was denying them the very freedom and equality on which the theory of original popular sovereignty, and the concept of contractual [[monarchy]], was based. Technically, the constituents of the group known as “the people” changes every time someone dies or is born. Does this mean that “the people” should reassemble every time someone dies or is born, to determine their sovereign wishes? | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==[[Family]] and [[state]]== | ||

| + | In medieval and early-modern Europe it was generally accepted that fathers possessed power over their children. Filmer argued that the state and the family were essentially the same entity, using the assumption that [[Genesis]] was a true historical record of the origins of human society. [[Adam]] had fatherly authority over his own children because he procreated them, and when those children themselves had children, Adam gained authority over them too, because he had authority over their fathers. According to the [[Bible]], Adam lived for several hundred years, and over the generations the number of people in his family must have multiplied until it was large enough to be regarded as a state, and not merely as a family. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When Adam died, the argument proceeded, his senior descendant by primogeniture inherited his powers, which were fatherly and political. The first state, therefore, originated from the first family. Divine [[providence]] later divided some states and created new ones, and sometimes altered the ruling dynasty or the form of government. But sovereign power was always derived from God alone and not from the people. The idea of the contractual origins of government, and of original freedom and equality, were fictions, since people had never been born free but were always subordinate to a father. The [[Commandment]] to “Honor thy father and thy mother,” was generally held to command obedience to magistrates also. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Filmer considered the power of a ruler over his state to be equal to the power of a father over his family. The king held the ultimate power of the father over all the families of his realm, and his subjects had no more right to disobey, resist, or bully their king than children did their father. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Influence== | ||

| + | Nine years after the publication of ''Patriarcha,'' at the time of the [[Glorious Revolution]] which banished the Stuarts from the throne, [[John Locke]] singled out Filmer as the most remarkable of the advocates of Divine Right, and specifically attacked him in the first part of the ''Two Treatises of Government,'' going into all his arguments and pointing out that even if the first steps of his argument were correct, the rights of the eldest born have been set aside so often that modern kings cannot claim the inheritance of authority which he asserted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Twentieth century scholars have viewed Filmer as a significant and interesting figure in his own right. His critique of contract theory and democracy is of particular interest to [[feminism|feminists]] and modern social and political theorists, who agree that it is almost impossible to create a system in which all people are have an equal voice. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Daly, James. 1979. ''Sir Robert Filmer and English Political Thought.'' Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802054331 |

| + | *Filmer, Robert, and Peter Laslett. 1984. ''Patriarcha and Other Political Works of Sir Robert Filmer.'' The Philosophy of John Locke. New York: Garland. ISBN 0824056043 | ||

| + | *Lein, Clayton D. 1995. ''British Prose Writers of the Early Seventeenth Century.'' ''Dictionary of Literary Biography,'' v. 151. Detroit: Gale Research Inc. ISBN 0810357127 | ||

| + | *Northrop, F. S. C. 1949. ''Ideological Differences and World Order, Studies in the Philosophy and Science of the World's Cultures.'' New Haven: Pub. for the Viking Fund [by] Yale Univ. Press. | ||

| + | *Robbins, John William. 1973. ''The Political Thought of Sir Robert Filmer.'' | ||

| + | *This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved December 15, 2022. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===General Philosophy Sources=== | ||

| + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[Category:philosophers]] | ||

{{credit|126238903}} | {{credit|126238903}} | ||

Latest revision as of 05:04, 15 December 2022

Sir Robert Filmer (1588 – May 26, 1653) was an English political theorist and one of the first absolutists. Born into an aristocratic family and knighted at the beginning of the reign of Charles I, he was a staunch supporter of the king when civil war broke out in 1642.

Filmer developed a political theory, based on natural law, which equated the authority of the king over his subjects with the authority of a father over his family. He used an argument based on the Book of Genesis to support the position that every king had inherited his patriarchy from Adam, and was therefore divinely ordained. The Parliament could only advise the king, who alone made laws, which proceeded purely from his will. The king himself was not bound by any law, because by nature it was impossible that a man should impose a law on himself. Filmer rejected the democratic ideal that all people were born free and equal, arguing that everyone was born subordinate to a father.

Life

Sir Robert Filmer was born at East Sutton, in Kent, in 1588, the eldest son of Sir Edward Filmer. Robert was the eldest of eighteen children. He matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1604. His friends included the High Church cleric, Peter Heylyn (1600-62), a great supporter of Archbishop William Laud. Knighted by Charles I at the beginning of his reign, he was an ardent supporter of the king's cause, and had a brother and son at court. In 1629, he inherited his father’s estates.

When civil war broke out in 1642, Filmer was too old to fight, but was a staunch Royalist. He was briefly imprisoned by Parliament, and his house in East Sutton is said to have been plundered by the parliamentarians ten times. He died May 26, 1653, in East Sutton, and is buried in the church there, surrounded by his descendants to the tenth generation, who were made baronets in his honor.

Background: The English Civil War

The English Civil War consisted of a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians (known as Roundheads) and Royalists (known as Cavaliers) between 1642 and 1651. Previous civil wars had been about succession to the throne; this conflict concerned the manner in which England was to be governed. Until the time of Charles I, the British Parliament served largely as an advisory council to the king and consisted of aristocrats and landed gentry who were responsible for collecting taxes for the throne. Charles I antagonized Parliament and aroused their suspicions. Upholding the Divine Right of Kings, he insisted that all his orders be obeyed without question. Against the wishes of Parliament, he sent a failed expedition to aid the Huguenots in France during the Thirty Years War, and dissolved Parliament when they disapproved. Early in his reign he married a French Catholic princess, arousing fears that his heirs would be Catholic. With the help of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, he began imposing High Anglican religious reforms on the Church of England, resulting in a rebellion in Scotland, which led to war. A series of three conflicts ended with a Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651.

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of his son Charles II, and the replacement of the English monarchy with first the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653) and then with a Protectorate (1653–1659), under the personal rule of Oliver Cromwell. It established a precedent that British monarchs could not govern without the consent of Parliament.

Works

Filmer was already middle-aged when the great controversy between the king and the Commons roused him into literary activity. His writings offer an example of the doctrines held by the most extreme section of the Divine Right party. Anarchy of a Limited and Mixed Monarchy, an attack upon a treatise on monarchy by Philip Hunton (1604-1682), who maintained that the king's prerogative is not superior to the authority of the houses of parliament, was published in 1648. Another pamphlet entitled The Power of Kings, was written in 1648, but not published until 1680, and his Observations concerning the Original of Government upon Mr Hobbes's Leviathan, Mr Milton against Salmasius, and H. Grotius' De jure belli ac pacis, appeared in 1652. During the exclusion crisis of 1679–80 Filmer's political tracts were reissued (1679), and his major work, Patriarcha, was published as Tory propaganda. It had been written around 1628, long before the Civil Wars and before Thomas Hobbes’ De Cive and Elements of Law were published in 1647, making Filmer England’s first absolutist. Much of Patriarcha was directed against Cardinal Robert Bellarmine and Francisco Suárez, who had criticized the Oath of Allegiance, a loyalty oath demanded of English Catholics in the wake of the Gunpowder Plot.

Political theory

Filmer's political theory was based on natural law. He believed that the institutions of family and the state were established to fulfill the purpose of human nature, and that the government of a family by the father was the true original and model of all government. In the beginning of the world, God gave authority to Adam, who had complete control over his descendants, even as to life and death. From Adam this authority was inherited by Noah; and Filmer quoted as not unlikely the tradition that Noah sailed up the Mediterranean and allotted the three continents of the Old World to the rule of his three sons. From Shem, Ham, and Japheth the patriarchs inherited the absolute power which they exercised over their families and servants; and from the patriarchs all kings and governors (whether a single monarch or a governing assembly) derive their authority, which is therefore absolute, and founded upon divine right.

The difficulty that a man by the secret will of God may unjustly attain to power which he has not inherited appeared to Filmer in no way to alter the nature of the power so obtained, for there is, and always shall be continued to the end of the world, a natural right of a supreme father over every multitude. The king was perfectly free from all human control. He could not be bound by the acts of his predecessors, for which he was not responsible; nor by his own, for it was impossible in nature that a man should impose a law on himself; the law must be imposed by someone other than the person bound by it.

Regarding the English constitution, he asserted, in his Freeholders Grand Inquest touching our Sovereign Lord the King and his Parliament (1648), that the Lords only give counsel to the king, the Commons only perform and consent to the ordinances of parliament, and the king alone is the maker of laws, which proceed purely from his will. He considered it monstrous that the people should judge or depose their king, for they would then be judges in their own cause.

Criticism of contract theorists

Filmer criticized contract theory for suggesting that democracy was the natural form of government instituted by God, when almost everyone agreed that democracy was little better than mob rule. Filmer also pointed out that “rule by the people" was a highly ambiguous term. If the term “the people” included women and children, why were they in fact excluded from political affairs? If it did not include women and children, why not? Saying that women and children were subordinate to husbands and fathers was denying them the very freedom and equality on which the theory of original popular sovereignty, and the concept of contractual monarchy, was based. Technically, the constituents of the group known as “the people” changes every time someone dies or is born. Does this mean that “the people” should reassemble every time someone dies or is born, to determine their sovereign wishes?

Family and state

In medieval and early-modern Europe it was generally accepted that fathers possessed power over their children. Filmer argued that the state and the family were essentially the same entity, using the assumption that Genesis was a true historical record of the origins of human society. Adam had fatherly authority over his own children because he procreated them, and when those children themselves had children, Adam gained authority over them too, because he had authority over their fathers. According to the Bible, Adam lived for several hundred years, and over the generations the number of people in his family must have multiplied until it was large enough to be regarded as a state, and not merely as a family.

When Adam died, the argument proceeded, his senior descendant by primogeniture inherited his powers, which were fatherly and political. The first state, therefore, originated from the first family. Divine providence later divided some states and created new ones, and sometimes altered the ruling dynasty or the form of government. But sovereign power was always derived from God alone and not from the people. The idea of the contractual origins of government, and of original freedom and equality, were fictions, since people had never been born free but were always subordinate to a father. The Commandment to “Honor thy father and thy mother,” was generally held to command obedience to magistrates also.

Filmer considered the power of a ruler over his state to be equal to the power of a father over his family. The king held the ultimate power of the father over all the families of his realm, and his subjects had no more right to disobey, resist, or bully their king than children did their father.

Influence

Nine years after the publication of Patriarcha, at the time of the Glorious Revolution which banished the Stuarts from the throne, John Locke singled out Filmer as the most remarkable of the advocates of Divine Right, and specifically attacked him in the first part of the Two Treatises of Government, going into all his arguments and pointing out that even if the first steps of his argument were correct, the rights of the eldest born have been set aside so often that modern kings cannot claim the inheritance of authority which he asserted.

Twentieth century scholars have viewed Filmer as a significant and interesting figure in his own right. His critique of contract theory and democracy is of particular interest to feminists and modern social and political theorists, who agree that it is almost impossible to create a system in which all people are have an equal voice.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Daly, James. 1979. Sir Robert Filmer and English Political Thought. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802054331

- Filmer, Robert, and Peter Laslett. 1984. Patriarcha and Other Political Works of Sir Robert Filmer. The Philosophy of John Locke. New York: Garland. ISBN 0824056043

- Lein, Clayton D. 1995. British Prose Writers of the Early Seventeenth Century. Dictionary of Literary Biography, v. 151. Detroit: Gale Research Inc. ISBN 0810357127

- Northrop, F. S. C. 1949. Ideological Differences and World Order, Studies in the Philosophy and Science of the World's Cultures. New Haven: Pub. for the Viking Fund [by] Yale Univ. Press.

- Robbins, John William. 1973. The Political Thought of Sir Robert Filmer.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.