Penicillin

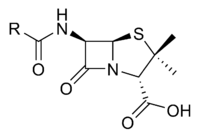

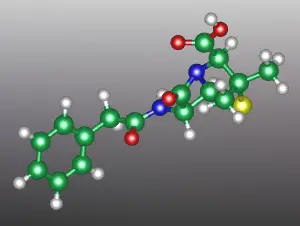

Penicillin (sometimes abbreviated PCN) refers to a group of β-lactam antibiotics used in the treatment of bacterial infections caused by susceptible, usually Gram-positive, organisms. The name “penicillin” can also be used in reference to a specific member of the penicillin group of fungi, such as the mold Penicillium chrysogenum. All penicillins possess the basic Penam Skeleton, which has the molecular formula R-C9H11N2O4S, where R is a variable side chain.

It is estimated that penicillin has saved at least 200 million lives since its first use as a medicine in 1942.

History

The serendipitous discovery of penicillin is usually attributed to Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming, though others had earlier noted the antibacterial effects of Penicillium. (Penicillium is a member of the deuteromycetes, fungi with no known sexual state. As it grows, it gives off the liquid referred to as penicillin.) Many ancient cultures, including the ancient Greeks and ancient Chinese, already used molds and other plants to treat infection. This worked because some molds produce antibiotic substances. However, they couldn't distinguish or distill the active component in the molds. There also are many old remedies where mould is involved. In Serbia and in Greece, moldy bread was a traditional treatment for wounds and infections.

Sir John Scott Burdon-Sanderson, who started out at St. Mary's Hospital 1852-1858 and as lecturer there 1854-1862, observed in 1870 that culture fluid covered with mold would produce no bacteria. In 1871, Joseph Lister, an English surgeon and the father of modern antisepsis, described that urine samples contaminated with moud did not allow the growth of bacteria and he also described the antibacterial action on human tissue on what he called Penicillium Glaucum. A nurse at Kings College Hospital, whose wounds did not respond to any antiseptic, was then given another substance which cured her, and Lister's registrar informed her that it was called Penicillium. Louis Pasteur and Jules Francois Joubert in 1877 had observed that cultures of the anthrax bacilli, when contaminated with molds, became inhibited. Some references say that Pasteur identified the strain as Penicillium notatum.

In 1928, Fleming, at his laboratory in St. Mary's Hospital (now one of Imperial College teaching hospitals) in London, noticed a halo of inhibition of bacterial growth around a contaminant blue-green mold on a Staphylococcus plate culture. Fleming concluded that the mold was releasing a substance that was inhibiting bacterial growth and lysing the bacteria. He grew a pure culture of the mold and discovered that it was a Penicillium mold, now known to be Penicillium chrysogenum (also known as P. notatum). Fleming coined the term "penicillin" to describe the filtrate of a broth culture of the Penicillium mold. Even in these early stages, penicillin was found to be most effective against Gram-positive bacteria, and ineffective against Gram-negative organisms and fungi. (Gram-positive (as opposed to gram-negative) refers to the characteristic blue-violet color reaction of certain types of bacteria in what is called the Gram-staining procedure. A major feature of gram-positive bacteria is the high percentage of peptidoglycan (sugar + amino acid molecule) in the cell wall.) Fleming expressed initial optimism that penicillin would be a useful disinfectant, being highly potent with minimal toxicity compared to antiseptics of the day, but particularly noted its laboratory value in the isolation of "Bacillus influenzae" (now Haemophilus influenzae) (Fleming 1929).

After further experiments, Fleming was convinced that penicillin could not last long enough in the human body to kill pathogenic bacteria and stopped studying penicillin after 1931, but restarted some clinical trials in 1934 and continued to try to find someone to purify it until 1940.

In 1939, Australian scientist Howard Walter Florey and a team of researchers (Ernst Boris Chain, A. D. Gardner, Norman Heatley, M. Jennings, J. Orr-Ewing and G. Sanders) at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford made significant progress in showing the in vivo bactericidal action of penicillin. (Bactericidal refers to inhibition of the growth or activity of bacteria, thus the prevention of infection.) Their attempts to treat humans failed due to insufficient volumes of penicillin, but they proved its harmlessness and effect in mice. Some of the pioneering trials of penicillin took place at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford. On March 14, 1942 John Bumstead and Orvan Hess became the first in the world to successfully treat a patient using penicillin (Saxon 1999, Krauss 1999).[1]

—>[2][3]

External links

- 'Face-to-Face' Interview with Sir John Cornforth, NL, who along with his wife Rita made important contributions to the work on Penicillin during the Second World War. Freeview video and transcript provided by the Vega Science Trust.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Fleming A. (1929). On the antibacterial action of cultures of a penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzæ.. Br J Exp Pathol 10 (31): 226–36.

- ↑ Saxon, W.. "Anne Miller, 90, first patient who was saved by penicillin", The New York Times, 1999-06-09.

- ↑ Krauss K, editor (1999). Yale-New Haven Hospital Annual Report (PDF). Yale-New Haven Hospital.

- ↑ Silverthorn, DU. (2004). Human physiology: an integrated approach.. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Education. ISBN 0-8053-5957-5.

- ↑ (2006) in Rossi S, editor: Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3.