Equiano, Olaudah

Nathan Cohen (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (19 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[ | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{submitted}}{{Copyedited}} |

| + | {{epname|Equiano, Olaudah}} | ||

| + | [[category:fix cite refs]] | ||

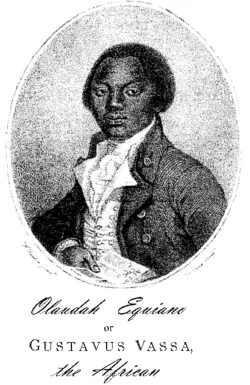

| − | '''Olaudah Equiano''' (''c''. | + | [[Image:Olaudah Equiano - Project Gutenberg eText 15399.png|thumb|250px]] |

| + | '''Olaudah Equiano''' (''c''.1745 – March 31, 1797), also known as '''Gustavus Vassa,''' was an eighteenth-century merchant seaman and writer of [[Africa|African]] descent who lived in Britain's American colonies and in Britain. Equiano is primarily remembered today for his autobiography, entitled ''The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano,'' which, with its detailed descriptions of the hardships of [[slavery]] and the culture of [[Nigeria|Nigerian]] Africa, became an international bestseller and helped to inspire the [[Abolitionism|abolitionist]] movement. In addition to being a leading influence in the abolition of slavery, Equiano is also a notable figure in [[Pan-Africanism|Pan-African]] literature, as his ''Interesting Narrative'' is believed to have influenced a number of later authors of [[slave narrative|slave narratives]], including [[Frederick Douglass]] and [[Booker T. Washington]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Although the historical and biographical accuracy of the ''Interesting Narrative'' has recently come into dispute, Equiano is nonetheless a major figure both in the politics and literature of the [[Middle Passage]]. | ||

==Early life and slavery== | ==Early life and slavery== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | By his own account, Olaudah Equiano's early life began in the region of ''Essaka'' near the River Niger, an Igbo-speaking region of [[Nigeria]], now in Anambra State. At an early age he was kidnapped by kinsmen and forced into domestic slavery in another native village in a region where the African chieftain hierarchy was tied to slavery. (Equiano 2005) | |

| − | + | At the age of eleven, he was sold to white slave traders and taken to the New World, and upon arrival was bought by Michael Pascal, a captain in the Royal Navy. As the slave of a naval captain, Equiano was afforded naval training. Equiano was able to travel extensively; during those travels he was sent to school in England by Pascal to learn to read, a generous gesture for a slave-owner at the time. Equiano mostly served as Pascal's personal servant but he was also expected to contribute in times of battle, and he served with distinction during the [[Seven Years' War]]. | |

| − | Later, Olaudah Equiano was sold | + | Later, Olaudah Equiano was sold on the island of Montserrat in the Leeward Islands of the [[Caribbean]]. Equiano was already able to read and write English which, together with his seamanship skills, made him too valuable to be bought for plantation labor. He was acquired by Robert King, a [[Quaker]] merchant from [[Philadelphia]]. King set Equiano to work on his shipping routes and in his stores, promising him, in 1765, that he could one day buy his own freedom if he saved forty pounds, the price King had paid for Equiano. King taught him to read and write more fluently and educated him in the [[Christian]] faith. He allowed Equiano to engage in his own profitable trading, enabling Equiano to come by the forty pounds honestly. In his early twenties, Equiano bought his own freedom. |

| − | King urged Equiano to stay on as a business | + | King urged Equiano to stay on as a business partner, but Equiano found it dangerous and limiting to remain in the colonies as a freedman. While loading a ship in Georgia, he had been almost kidnapped back into slavery. Equiano returned to Britain, where he returned to a life at sea in the Royal Navy. (McKay 2006) |

| − | + | ==Pioneer of the Abolitionist cause== | |

| − | + | After several years of travels and trading, Equiano moved to [[London]], becoming involved in the [[abolitionism|abolitionist movement]]. He proved to be a popular and powerful speaker, and was introduced to many senior and influential abolitionists who encouraged him to write and publish his life story. He was supported financially by philanthropic abolitionists and religious benefactors; his lectures and preparation for the book were promoted by, among others, Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. His account, published as ''The Interesting Narrative,'' exceeded all expectations for the quality of its imagery and literary style, as well as its profound invectives against those who had failed to join the cause of abolition. ''The Interesting Narrative'' was first published in 1789 and rapidly went through several editions. It is one of the earliest known examples of published writing by an African writer. Its first-hand account of slavery and of the travels and experiences of an eighteenth-century black immigrant in America and Britain had a profound impact on white people's perceptions of African people. | |

| − | + | The book not only furthered the abolitionist cause, but also made Equiano's fortune. It gave him independence from his benefactors, enabling him to fully chart his own life and purpose, and develop his interest in working to improve economic, social, and educational conditions in Africa, particularly in [[Sierra Leone]]. | |

| − | + | ==Controversy over origin== | |

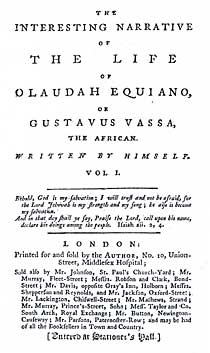

| − | + | [[Image:The interresting narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano.jpg|thumb|250px|right|Front page of ''The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa'']] | |

| − | + | Vincent Carretta, a professor of literature and author of ''Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man,'' points out that a major problem facing any biographer is how to deal with Equiano's account of his origins: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | Vincent Carretta, a professor of literature and author of ''Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man'' | + | <blockquote>Equiano was certainly African by descent. The circumstantial evidence that Equiano was also African American by birth and African British by choice is compelling but not absolutely conclusive. Although the circumstantial evidence is not equivalent to proof, anyone dealing with Equiano's life and art must consider it. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <blockquote> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | This current doubt about his origins | + | This current doubt about his origins arises from records that suggest Equiano may have been born in South Carolina. Most importantly, the baptismal record at St. Margaret's Church in Westminster, dated February 9, 1759, records an Olaudah Equiano born in Carolina, and a navy muster roll of 1773 records Equiano's birthplace as South Carolina. Some sections of ''The Interesting Narrative,'' and particularly the section on the [[Middle Passage]], contain a number of historical discrepancies and errors. Moreover, the passages in ''The Interesting Narrative'' describing life in Africa very closely resemble the written accounts of a number of other published Africans whose works would have been available to Equiano at the time of writing. Although the proof is not absolute, it suggests that Equiano may have fabricated portions of his autobiography. Other academics have suggested that an oral history supporting ''The Interesting Narrative'' exists in Nigeria near the regions where Equiano claimed to have been born. More recent scholarship has also favored Olaudah Equiano's own account of his African birth, but the dispute over the validity of ''The Interesting Narrative'' remains unresolved. |

| − | Historians have never discredited the accuracy of Equiano's narrative, nor the power it had to support the abolitionist cause, particularly in Britain during the 1790s, but parts of Equiano's account of the | + | Historians have never discredited the accuracy of Equiano's narrative, nor the power it had to support the abolitionist cause, particularly in Britain during the 1790s, but parts of Equiano's account of the Middle Passage may have been based on already published accounts or the experiences of those he knew. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Family in Britain== | ==Family in Britain== | ||

| − | At some point, after having traveled widely, Olaudah Equiano appears to have decided to settle in Britain and raise a family. Equiano | + | At some point, after having traveled widely, Olaudah Equiano appears to have decided to settle in Britain and raise a family. Equiano settled in Soham, Cambridgeshire, where, on April 7, 1792, he married Susannah Cullen, a local girl, in St. Andrew's Church. He announced his wedding in every edition of his autobiography from 1792 onwards, and it has been suggested his marriage mirrored his anticipation of a commercial union between Africa and England. The couple settled in the area and had two daughters, Anna Maria, born October 16, 1793 and Joanna, born April 11, 1795. |

| − | Susannah died in February | + | Susannah died in February 1796 at the age of 34, and Equiano died a year after that on March 31, 1797, at the age of 52. Soon after, the elder daughter died at the age of four, leaving Joanna to inherit Equiano's estate which was valued at £950—a considerable sum, worth approximately £100,000 today. Equiano's will demonstrates the sincerity of his religious and social beliefs. Had his daughter Joanna died before reaching the age of inheritance (twenty-one), his will stipulated that half of his wealth would go to the Sierra Leona Company for the continued provision of help to West Africans, and half to the Missionary Society, the organization that by the early nineteenth century had become well known world-wide as a non-denominational organization promoting education overseas. |

| − | == | + | == References == |

| − | + | * Carretta, Vincent. 2005. ''Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man.'' Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0143038427 | |

| − | + | * Equiano, Olaudah. 2001. ''The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself,'' edited by Werner Sollors. New York: Norton. ISBN 0393974944 | |

| − | + | * Equiano, Olaudah. 2005. ''The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African.'' Gutenberg Project. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15399/15399-h/15399-h.htm. Retrieved October 11, 2007. | |

| − | + | * McKay, John. 2006. ''A History of Western Society,'' 8th ed., Advanced Placement edition. Houghton Mifflin, p. 653. | |

| − | + | * Walvin, James. 1998. ''An African's Life: The Life and Times of Olaudah Equiano.'' London: Cassell. ISBN 0304702145 | |

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http://www.newsreel.org/nav/title.asp?tc=CN0086&s=A%20son%20of%20Africa A SON OF AFRICA] | + | All links retrieved November 17, 2022. |

| − | * {{gutenberg author| id=Olaudah+Equiano | name=Olaudah Equiano}} | + | *[http://www.newsreel.org/nav/title.asp?tc=CN0086&s=A%20son%20of%20Africa A SON OF AFRICA]. |

| − | *[http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/equiano_olaudah.shtml Olaudah Equiano] from | + | * {{gutenberg author| id=Olaudah+Equiano | name=Olaudah Equiano}}. |

| − | + | *[http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/equiano_olaudah.shtml Olaudah Equiano] from BBC.co.uk. | |

| − | *[http://www.brycchancarey.com/equiano/nativity.htm | + | *[http://www.brycchancarey.com/equiano/nativity.htm Where Was Olaudah Equiano Born?]. |

| − | *[http://www.brycchancarey.com/equiano/index.htm Olaudah Equiano, or, Gustavus Vassa, the African] | + | *[http://www.brycchancarey.com/equiano/index.htm Olaudah Equiano, or, Gustavus Vassa, the African]. |

| − | *[http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9032842/Olaudah-Equiano Encyclopaedia Britannica, Olaudah Equiano - full access article] | + | *[http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9032842/Olaudah-Equiano Encyclopaedia Britannica, Olaudah Equiano - full access article]. |

| − | + | *[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1p276.html Africans in America - Olaudah Equiano]. | |

| − | *[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1p276.html Africans in America - Olaudah Equiano] | + | *[http://www.brycchancarey.com/equiano/biog.htm Olaudah Equiano: A Critical Biography]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.brycchancarey.com/equiano/biog.htm | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Writers and poets]] |

{{credit|105967593}} | {{credit|105967593}} | ||

Latest revision as of 00:02, 18 November 2022

Olaudah Equiano (c.1745 – March 31, 1797), also known as Gustavus Vassa, was an eighteenth-century merchant seaman and writer of African descent who lived in Britain's American colonies and in Britain. Equiano is primarily remembered today for his autobiography, entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, which, with its detailed descriptions of the hardships of slavery and the culture of Nigerian Africa, became an international bestseller and helped to inspire the abolitionist movement. In addition to being a leading influence in the abolition of slavery, Equiano is also a notable figure in Pan-African literature, as his Interesting Narrative is believed to have influenced a number of later authors of slave narratives, including Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington.

Although the historical and biographical accuracy of the Interesting Narrative has recently come into dispute, Equiano is nonetheless a major figure both in the politics and literature of the Middle Passage.

Early life and slavery

By his own account, Olaudah Equiano's early life began in the region of Essaka near the River Niger, an Igbo-speaking region of Nigeria, now in Anambra State. At an early age he was kidnapped by kinsmen and forced into domestic slavery in another native village in a region where the African chieftain hierarchy was tied to slavery. (Equiano 2005)

At the age of eleven, he was sold to white slave traders and taken to the New World, and upon arrival was bought by Michael Pascal, a captain in the Royal Navy. As the slave of a naval captain, Equiano was afforded naval training. Equiano was able to travel extensively; during those travels he was sent to school in England by Pascal to learn to read, a generous gesture for a slave-owner at the time. Equiano mostly served as Pascal's personal servant but he was also expected to contribute in times of battle, and he served with distinction during the Seven Years' War.

Later, Olaudah Equiano was sold on the island of Montserrat in the Leeward Islands of the Caribbean. Equiano was already able to read and write English which, together with his seamanship skills, made him too valuable to be bought for plantation labor. He was acquired by Robert King, a Quaker merchant from Philadelphia. King set Equiano to work on his shipping routes and in his stores, promising him, in 1765, that he could one day buy his own freedom if he saved forty pounds, the price King had paid for Equiano. King taught him to read and write more fluently and educated him in the Christian faith. He allowed Equiano to engage in his own profitable trading, enabling Equiano to come by the forty pounds honestly. In his early twenties, Equiano bought his own freedom.

King urged Equiano to stay on as a business partner, but Equiano found it dangerous and limiting to remain in the colonies as a freedman. While loading a ship in Georgia, he had been almost kidnapped back into slavery. Equiano returned to Britain, where he returned to a life at sea in the Royal Navy. (McKay 2006)

Pioneer of the Abolitionist cause

After several years of travels and trading, Equiano moved to London, becoming involved in the abolitionist movement. He proved to be a popular and powerful speaker, and was introduced to many senior and influential abolitionists who encouraged him to write and publish his life story. He was supported financially by philanthropic abolitionists and religious benefactors; his lectures and preparation for the book were promoted by, among others, Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. His account, published as The Interesting Narrative, exceeded all expectations for the quality of its imagery and literary style, as well as its profound invectives against those who had failed to join the cause of abolition. The Interesting Narrative was first published in 1789 and rapidly went through several editions. It is one of the earliest known examples of published writing by an African writer. Its first-hand account of slavery and of the travels and experiences of an eighteenth-century black immigrant in America and Britain had a profound impact on white people's perceptions of African people.

The book not only furthered the abolitionist cause, but also made Equiano's fortune. It gave him independence from his benefactors, enabling him to fully chart his own life and purpose, and develop his interest in working to improve economic, social, and educational conditions in Africa, particularly in Sierra Leone.

Controversy over origin

Vincent Carretta, a professor of literature and author of Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man, points out that a major problem facing any biographer is how to deal with Equiano's account of his origins:

Equiano was certainly African by descent. The circumstantial evidence that Equiano was also African American by birth and African British by choice is compelling but not absolutely conclusive. Although the circumstantial evidence is not equivalent to proof, anyone dealing with Equiano's life and art must consider it.

This current doubt about his origins arises from records that suggest Equiano may have been born in South Carolina. Most importantly, the baptismal record at St. Margaret's Church in Westminster, dated February 9, 1759, records an Olaudah Equiano born in Carolina, and a navy muster roll of 1773 records Equiano's birthplace as South Carolina. Some sections of The Interesting Narrative, and particularly the section on the Middle Passage, contain a number of historical discrepancies and errors. Moreover, the passages in The Interesting Narrative describing life in Africa very closely resemble the written accounts of a number of other published Africans whose works would have been available to Equiano at the time of writing. Although the proof is not absolute, it suggests that Equiano may have fabricated portions of his autobiography. Other academics have suggested that an oral history supporting The Interesting Narrative exists in Nigeria near the regions where Equiano claimed to have been born. More recent scholarship has also favored Olaudah Equiano's own account of his African birth, but the dispute over the validity of The Interesting Narrative remains unresolved.

Historians have never discredited the accuracy of Equiano's narrative, nor the power it had to support the abolitionist cause, particularly in Britain during the 1790s, but parts of Equiano's account of the Middle Passage may have been based on already published accounts or the experiences of those he knew.

Family in Britain

At some point, after having traveled widely, Olaudah Equiano appears to have decided to settle in Britain and raise a family. Equiano settled in Soham, Cambridgeshire, where, on April 7, 1792, he married Susannah Cullen, a local girl, in St. Andrew's Church. He announced his wedding in every edition of his autobiography from 1792 onwards, and it has been suggested his marriage mirrored his anticipation of a commercial union between Africa and England. The couple settled in the area and had two daughters, Anna Maria, born October 16, 1793 and Joanna, born April 11, 1795.

Susannah died in February 1796 at the age of 34, and Equiano died a year after that on March 31, 1797, at the age of 52. Soon after, the elder daughter died at the age of four, leaving Joanna to inherit Equiano's estate which was valued at £950—a considerable sum, worth approximately £100,000 today. Equiano's will demonstrates the sincerity of his religious and social beliefs. Had his daughter Joanna died before reaching the age of inheritance (twenty-one), his will stipulated that half of his wealth would go to the Sierra Leona Company for the continued provision of help to West Africans, and half to the Missionary Society, the organization that by the early nineteenth century had become well known world-wide as a non-denominational organization promoting education overseas.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carretta, Vincent. 2005. Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0143038427

- Equiano, Olaudah. 2001. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself, edited by Werner Sollors. New York: Norton. ISBN 0393974944

- Equiano, Olaudah. 2005. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Gutenberg Project. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15399/15399-h/15399-h.htm. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- McKay, John. 2006. A History of Western Society, 8th ed., Advanced Placement edition. Houghton Mifflin, p. 653.

- Walvin, James. 1998. An African's Life: The Life and Times of Olaudah Equiano. London: Cassell. ISBN 0304702145

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- A SON OF AFRICA.

- Works by Olaudah Equiano. Project Gutenberg.

- Olaudah Equiano from BBC.co.uk.

- Where Was Olaudah Equiano Born?.

- Olaudah Equiano, or, Gustavus Vassa, the African.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Olaudah Equiano - full access article.

- Africans in America - Olaudah Equiano.

- Olaudah Equiano: A Critical Biography.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.