Muhammad Ali Dynasty

| Muhammad Ali Dynasty (Alawiyya Dynasty) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Country | Egypt and Sudan | ||

| Titles | Wāli, self-declared as Khedive (1805-1867) Khedive officially recognized (1867-1914) Sultan (1914-1922) King (1922-1953) | ||

| Founder | Muhammad Ali Pasha | ||

| Final ruler | Fuad II | ||

| Current head | Fuad II | ||

| Founding year | 1805: Muhammad Ali's consolidation of power | ||

| Deposition | 1953: Abolition of monarchy following Egyptian Revolution | ||

| Ethnicity | Egyptian of Albanian-Macedonian descent. | ||

The Muhammad Ali Dynasty (Usrat Muhammad 'Ali) was the ruling dynasty of Egypt and Sudan from the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. It is named after Muhammad Ali Pasha, regarded as the founder of modern Egypt. It was also more formally known as the Alawiyya Dynasty (al-Usra al-'Alawiyya), although it should not be confused with ruling the Alawiyya Dynasty of Morocco, to which it has no relation. Because a majority of the rulers from this dynasty bore the title Khedive, it was often referred to by contemporaries as the "Khedival Dynasty." From 1882, when the British occupied Egypt, they effectively ruled through the Khedive. They initially intervened in Egyptian affairs to oversee the Khedive's finances; he had defaulted on loans owed to European banks. In 1914, when they formally annexed Egypt, the ruler's title was changed to "Sultan." Following independence in 1922, the Sultan became "king." Farouk of Egypt (1936-52) jeopardized the monarchy by interfering in government and by living a lifestyle that alienated most of his subjects. He was deposed and in a little less than a year, the monarchy was abolished.

Under the Muhammad Ali Dynasty, Egypt became an industrialized nation. Many public work projects were carried out, including the constructions of railways, canals, schools and irrigation systems. A high priority was given to education and many Egyptians were sent to Europe, especially to France, to acquire specific skills. The rulers also began to experiment with democracy. Unfortunately, the kings were ambivalent about democracy and could not resist interfering in governance, continually dismissing cabinets and appointing minority governments that did not enjoy the support of the people. Their flamboyant life-style insulted many of their subjects, who were struggling with poverty, feeding resentment and the revolution of 1952. The Dynasty fell because its members failed to respect the will of the people, as expressed through elected representatives and because their life-style was regarded as inappropriate and even profligate.

Origins of the Dynasty

Muhammad Ali was an Albanian commander of the Ottoman army that was sent to drive Napoleon Bonaparte's forces out of Egypt, but upon the French withdrawal, he seized power himself and forced the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II to recognize him as Wāli, or Governor (Arabic: والي) of Egypt in 1805.

Muhammad Ali transformed Egypt into a regional power which he saw as the natural successor to the decaying Ottoman Empire. He summed up his vision for Egypt in these words:

I am well aware that the (Ottoman) Empire is heading by the day toward destruction and it will be difficult for me to save her. And why should I seek the impossible. … On her ruins I will build a vast kingdom … up to the Euphrates and the Tigris.[1]

At the height of his power, Muhammad Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha's military strength did indeed threaten the very existence of the Ottoman Empire as he sought to supplant the Ottoman's with his own. Ultimately, the intervention of the Great Powers prevented Egyptian forces from marching on Constantinople. After this, his dynasty's rule would be limited to Africa. Muhammad Ali had conquered Sudan in the first half of his reign and Egyptian control would be consolidated and expanded under his successors, most notably Ibrahim Pasha's son Ismai'l I.

Khedivate and British occupation

Though Muhammad Ali and his descendants used the title of Khedive in preference to the lesser Wāli, this was not recognized by the Ottoman Porte until 1867 when Sultan Abdul-Aziz officially sanctioned its use by Isma'il Pasha and his successors. In contrast to his grandfather's policy of war against the Porte, Ismai'l sought to strengthen the position of Egypt and Sudan and his dynasty using less confrontational means, and through a mixture of flattery and bribery, Ismai'l secured official Ottoman recognition of Egypt and Sudan's virtual independence. This freedom was severely undermined in 1879 when the Sultan colluded with the Great Powers to depose Ismai'l in favor of his son Tewfik. Three years later, Egypt and Sudan's freedom became little more than symbolic when Great Britain invaded and occupied the country, ostensibly to support Khedive Tewfik against his opponents in Ahmed Orabi's nationalist government. While the Khedive would continue to rule over Egypt and Sudan in name, in reality, ultimate power resided with the British Consul General. Famously, Baring, Evelyn, 1st Earl of Cromer was in office from 1883, soon after the British occupation, until 1907. Egypt was considered of strategic significance to protect Britain's interest in the Suez Canal and the route to the jewel in Britain's colonial crown, India.

In defiance of the Egyptians, the British proclaimed Sudan to be an Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, a territory under joint British and Egyptian rule rather than an integral part of Egypt. This was continually rejected by Egyptians, both in government and in the public at large, who insisted on the "unity of the Nile Valley," and would remain an issue of controversy and enmity between Egypt and Britain until Sudan's independence in 1956.

Sultanate and Kingdom

In 1914, Khedive Abbas II sided with the Ottoman Empire which had joined the Central Powers in the First World War, and was promptly deposed by the British in favor of his uncle Husayn Kamil. The legal fiction of Ottoman sovereignty over Egypt and Sudan, which had for all intents and purposes ended in 1805, was officially terminated, Husayn was declared Sultan of Egypt and Sudan, and the country became a British Protectorate. With nationalist sentiment rising, Britain formally recognized Egyptian independence in 1922, and Husayn's successor, Sultan Fuad I, substituted the title of King for Sultan. However, British occupation and interference in Egyptian and Sudanese affairs persisted. Of particular concern to Egypt was Britain's continual efforts to divest Egypt of all control in Sudan. To both the King and the nationalist movement, this was intolerable, and the Egyptian Government made a point of stressing that Fuad and his son King Farouk I were "King of Egypt and Sudan."

Although the Dynasty's power was only nominal, from the end of the nineteenth century as Ottoman power weakened and nationalist and pan-Arabist movements gained momentum, members of the dynasty contemplated the possibility of replacing the Ottomans as Caliph;

There were persistent rumors that he [the Khedive] planned taking the Sultan's place as temporal and spiritual lord—Sultan and Caliph—of the Arabic speaking provinces of the empire, thereby splitting the empire in half. A variant was the rumor that he planned to annex the Moslem holy places in Arabia and establish a caliph there under his protection.[2]

The British, already contemplating the demise of the Ottoman Empire, were quite happy with these possibilities, understanding "that the achievement of any such plan would bring greatly enlarged authority to themselves."[2] According to Fromkin, the British at this time thought they could "capture Islam" by arranging, after World War I for "their own nominee" who would be an Arab whom they could "insulate … from the influence of Britain's European rivals" since the British Navy could easily control the "coastline of the Arabian peninsula." Once they had installed their choice of caliph, the British could "gain control of Islam."[3] Although the ambitions of the Egyptian Khedives did not succeed, it was from their base in Egypt that the British encouraged the Arab Revolt during World War I and promised the Sharif of Mecca an Arab state.

Modernization and British occupation

Under the Muhammad Ali Dynasty, a process of modernization took place that raised Egypt's status internationally and greatly improved the nation's infrastructure including a post service, railway, new harbor installations, irrigation systems, canals and schools. Factories were built to produce as much material locally as possible instead of relying on imports, beginning an industrialization process, the first in the Arab world. However, paying for these as well as wars bankrupted the state, opening the way for British and French intervention to oversee Egypt's finances when he defaulted on loan repayment.[4] On the one hand, Egypt's revenue doubled under Isma'il Pasha. On the other, he was reckless in taking out high-interest loans, running up a debt of ninety million pounds sterling. Part of the arrangement was for the Khedive, Isma'il Pasha, to delegate authority to a parliament, in which the Finance Minister and the Minister of Works were European (Cromer was Finance Minister). Known as Dual Control, this arrangement began in 1878. Isma'il Pasha, however, was soon replaced by his son, Tewfik. At almost the same time, the European powers were intervening in the financial administration of the Ottoman Empire, also to protect the interests of foreign bond-holders. In May 1892, a military revolt began against European rule. France decided not to assist with crushing the rebellion, which the British did by sending an occupation force. This marked the beginning of de facto British rule. British troops remained in Egypt from 1882 until 1965.

The legal system and the education system under the Muhammad Ali Dynasty was greatly influenced by France. Although Napoleon did not stay in Egypt very long, he left behind a party of scientists and scholars. Traffic was two-way; they studied Ancient Egypt and Egyptians studied them, or rather their learning. Elite Egyptians began to study in France, sometimes sent by the government to acquire specific skills while French became the language of polite society.

Modernist Islam

Interaction with French ideals of liberty, equality and with democratic principles impacted Muslim scholarship and thinking in Egypt. During the Muhammad Ali Dynasty, some of the most distinguished reformist Muslim thinkers were Egyptian. The ancient university of AL-Azhar, Cairo was modernized under Muhammad 'Abdhu, while Qasim Amin and Bahithat al-Badiya advocated female emancipation.

Governance

Muhammad Ali had convened an advisory council in 1824. His son started election for membership of the council in 1866. Although the council could not legislate, it could make recommendations. Elections were held for this in 1881, when legislative power was vested in the new Assembly. This also had a Cabinet that was responsible to parliament. This was suspended after the British occupation. A new General Assembly was created in 1883. In 1913, this became the Legislative Assembly, which was suspended during World War I. Following independence, a new constitution became effective, with elected upper and lower chambers. Technically, the Kings (the title changed in 1922) were constitutional monarchs but they did their best to rule autocratically, constantly dismissing governments and choosing their own nominees instead of those who could command votes in the house. It was this interference in constitutional governance, especially by Farouk, that led to the dissolution of the monarchy. The monarchy lost touch with the people, becoming increasingly unpopular. The period "1923-1952 witnessed the succession of 40 cabinets and cabinet reshuffles" which did little to establish political stability.[5]

Dissolution

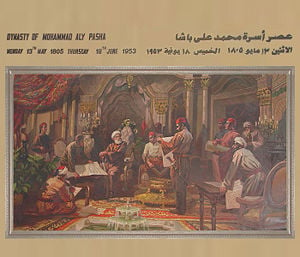

The reign of Farouk was characterized by ever increasing nationalist discontent over the British occupation, royal corruption and incompetence, and the disastrous 1948 Arab-Israeli War. All these factors served to terminally undermine Farouk's position and paved the way for the Revolution of 1952. Farouk did not help matters by his flamboyant and expensive life-style even though many Egyptians experienced poverty and by his constant interference in parliament, appointing a string of minority governments. Farouk was forced to abdicate in favor of his infant son Ahmed-Fuad who became King Fuad II, while administration of the country passed to the Free Officers Movement under Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser. The infant king's reign lasted less than a year and on June 18 1953, the revolutionaries abolished the monarchy and declared Egypt a republic, ending a century and a half of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty's rule and thousands of years of monarchy in one form or another.

Reigning members of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty (1805-1953)

Wālis, self-declared as Khedives (1805-1867)

- Muhammad Ali (July 9, 1805-September 1, 1848)

- Ibrahim (reigned as Wāli briefly during his father's incapacity) (September 1, 1848-November 10, 1848)

- Muhammad Ali (restored) (November 10, 1848-August 2, 1849)

- Abbas I (August 2, 1849-July 13, 1854)

- Sa‘id I (July 13, 1854-January 18, 1863)

- Ismai'l I (January 18, 1863-June 8, 1867)

Khedives (1867-1914)

- Ismai'l I (June 8, 1867-June 26, 1879)

- Tewfik I (June 26, 1879-January 7, 1892)

- Abbas II (January 8, 1892-December 19, 1914)

Sultans (1914-1922)

- Husayn I (December 19, 1914-October 9, 1917)

- Fuad I (October 9, 1917-March 16, 1922)

Kings (1922-1953)

- Fuad I (March 16, 1922-April 28, 1936)

- Farouk I (April 28, 1936-July 26, 1952)

- Prince Muhammad Ali Tewfik (Chairman Council of Regency during Farouk I's minority) (April 28, 1936-July 29, 1937)

- Fuad II (July 26, 1952-June 18, 1953)

- Prince Muhammad Abdul Moneim (Chairman Council of Regency during Fuad II's minority) (July 26, 1952-June 18, 1953)

Non ruling members

- Prince Mustafa Fazl Pasha

- Prince Mohammed Ali Tewfik

- Prince Muhammad Abdul Moneim

- Princess Fawzia Shirin

- Muhammad Ali, Prince of Said

- Narriman Sadek

- Nazli Sabri

- Mahmud Dramali Pasha

Legacy

Under the Muhammad Ali Dynasty, Egypt became an industrialized nation, began to experiment with democracy and earned a respected place in the world community. Unfortunately, the kings were ambivalent about democracy and could not resist interfering in governance, continually dismissing cabinets and appointing minority governments that did not enjoy the support of the people. Their flamboyant life-style insulted those of their subjects who were struggling with poverty, feeding resentment and the revolution of 1952. If the rulers had respected the will of the people as expressed through the elected representatives and lived more modestly, the Dynasty might have survived.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ʻAbbās, and Amira El Azhary Sonbol. 1998. The Last Khedive of Egypt: Memoirs of Abbas Hilmi II. Reading, UK: Ithaca Press. ISBN 9780863722080.

- Daly, M.W. 1998. The Cambridge History of Egypt. Volume 2, Modern Egypt, from 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511004223.

- Fromkin, David. 1989. A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East, 1914-1922. New York, NY: H. Holt. ISBN 9780805008579.

- Hassan, Hassan. 2000. In the House of Muhammad Ali: A Family Album, 1805-1952. Cairo, EG: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774245541.

- Mackesy, Piers. 2002. British Victory in Egypt, 1801 the End of Napoleon's Conquest. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780203324981.

- Pakenham, Thomas. 1992. The Scramble for Africa: White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. New York, UK: Avon Books. ISBN 9780380719990.

- Sowell, Kirk H. 2004. The Arab World: An Illustrated History. New York, UK: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 9780781809900.

- Stadiem, William. 1991. Too Rich: The High Life and Tragic Death of King Farouk. New York, UK: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 9780881846294.

- Tugay, Emine Foat. 1974. Three Centuries; Family Chronicles of Turkey and Egypt. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780837171173.

- Vatikiotis, P.J., and P.J. Vatikiotis. 1991. The History of Modern Egypt: From Muhammad Ali to Mubarak. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801842146.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.