Miyamoto Musashi

Miyamoto Musashi (宮本 武蔵, Miyamoto Musashi; c. 1584 - June 13, 1645), (childhood name Miyamoto Bennosuke or Miyamoto Musana), was the best-known Japanese swordsman. He is believed to have been one of the most skilled swordsmen in Japanese history. Musashi, as he is often known, became legendary through his outstanding swordsmanship in numerous duels, starting when he was thirteen years old. He is the founder of the Hyoho Niten Ichi-ryu, or Nito Ryu style (two-sword style) of swordsmanship, and wrote Go Rin No Sho (The Book of Five Rings), a book on strategy, tactics, and practical philosophy still studied today by all types of people—from martial artists to business professionals. Musashi emphasized the "Way of Strategy," taking an overall view of a conflict and devising the best method for countering the enemy's attack, rather than just focusing on technical skills and execution. He taught his students to anticipate an opponent's next move and thwart it. Though not overtly religious, Musashi practiced Zen, and taught that success in combat was based on a person's character and mental preparation. Musashi developed the technique of holding the long sword with one hand instead of two, and often fought with a long sword in one hand and a short sword or other weapon in the other hand.

As a swordsman, Mushashi trained to develop his physical strength. His original intention was only to become a strong swordsman, but he gradually came to realize that the strategic principles and practical philosophy he discovered were applicable to diverse phases of human life. He constantly tested his insights in a series of real life-or-death sword fights, and proved the validity of his theories by winning again and again. In his later life, he retreated to the Reigandō cave where he lived as a hermit and wrote his best-known book, The Book of Five Rings, while engaging in Zen meditation. In his The Book of Five Rings he emphasizes that warriors should be well-rounded and have an understanding of other professions as well as warfare. He said that one could apply expertise gained from one profession to the successful execution of work in other fields. Especially in his later life, Musashi also developed the more artistic side of bushido. He made various Zen brush paintings, excelled in calligraphy, and sculpted wood and metal. Musashi is a legend and one of the most popular figures in Japanese cultural history. Many works have been produced in various genres, from novels and business books to films, television series and plays, featuring Musashi as a hero.

Biography

Birth

Miyamoto Musashi's early life is fairly well documented, but the sources conflict. The place and date of his birth are uncertain. It is generally accepted that his elder brother, Shirota, was born in 1578 (dying in 1660), and that Musashi himself was born into a samurai family called the Hirata, in the village of Miyamoto (in present-day Okayama (then Sakushu, west of Kyoto), in the province of Mimasaka. The village of Banshu has been suggested as another possible birthplace. His family owed allegiance to the Shinmen clan; Musashi later alluded to this relationship in the formal introduction to the Go Rin No Sho, giving his full name as Shinmen Musashi no Kami Fujiwara no Genshin.

His father is thought to have been Hirata Munisai (or Miyamoto Munisai, or Miyamoto Muninosuke), a vassal to Lord Shinmen. A skilled martial artist in his own right, he was renowned as a master of the jitte and a sword adept. The jitte "ten-hand" is a specialized weapon, a short metal truncheon that was used by constables. In his youth, he won two out of three bouts against a master swordsman named Yoshioka in front of the then-shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki; the shogun granted him the title "Best in Japan." Munisai also taught his jitte techniques in a local dojo (training hall). His tomb says he died in 1580, which conflicts with the accepted birth date of 1584 for Musashi. The family genealogy of the extant Miyamoto family gives Musashi’s year of birth as 1583. Kenji Tokitsu has suggested that the accepted birth date of 1584 for Musashi is probably wrong, being based on a literal interpretation that Musashi was exactly sixty years old when he wrote the introduction to the Go Rin No Sho; he probably was in his sixties.

Childhood

From the age of seven, Musashi was raised as a Buddhist by his uncle, Dorinbo (or Dorin), in Shoreian temple, near Hirafuku. Both Dorin and Tasumi, Musashi's uncle by marriage, educated him in Buddhism and basic skills such as writing and reading. (This education is possibly the basis for Yoshikawa Eiji's fictional account of the education of Musashi by the historical Zen monk Takuan.) He was apparently trained by Munisai in the sword, and in the family art of the jitte. This training lasted only a short time—until 1589—when Munisai was ordered by Shinmen Sokan to kill his student, Honiden Gekinosuke. The Honiden family then forced Munisai to move four kilometers away to the village of Kawakami.

It is said that Musashi contracted eczema in his infancy, and that this adversely affected his appearance. Another story claims that he never took a bath because he did not want to be surprised unarmed. These and many other details are probably embellishments to the legend of Musashi rather than actual facts.

Training in Swordsmanship

The name "Musashi" was thought to have been taken from a warrior monk named Musashibō Benkei, who served under Minamoto no Yoshitsune and mastered the use of more than nine weapons. It is said that he may have studied at the Yoshioka ryu school, which Musashi defeated single-handedly during his later years.

First Duel

I have trained in the way of strategy since my youth, and at the age of thirteen I fought a duel for the first time. My opponent was called Arima Kihei, a sword adept of the Shinto ryu, and I defeated him. At the age of sixteen I defeated a powerful adept by the name of Akiyama, who came from the prefecture of Tajima. At the age of twenty-one I went up to Kyoto and fought duels with several adepts of the sword from famous schools, but I never lost. -Musashi Miyamoto, Go Rin no Sho

In the introduction to The Book of Five Rings, Musashi relates that his first successful duel was fought at the age of thirteen, against a lesser-skilled Samurai named Arima Kihei who fought using the Shintō-ryū style, founded by Tsukahara Bokuden (b. 1489, d. 1571). The Hyoho Senshi Denki (Anecdotes about the Deceased Master) gives the following account of the duel. In 1596, when Musashi was 13, Arima Kihei, who was traveling to hone his art, posted a public challenge in Hirafuku-mura. Musashi wrote his name on the challenge. A messenger came to his uncle Dorin's temple, where Musashi was staying, to inform Musashi that his challenge to a duel had been accepted by Kihei. Dorin, shocked, tried to decline the challenge on behalf of Musashi, but Kihei refused to drop the duel, saying that only Musashi’s public apology at the scheduled meeting could clear his honor. When the time set for the duel arrived, the monk began apologizing for Musashi, who leaps into the ring with a piece of wood shaped like a sword and shouted a challenge to Kihei. Kihei attacked with a wakizashi, but Musashi threw Kihei, and when Kihei tried to get up, Musashi struck him between the eyes and then beat him to death.

Travels and Duels

In 1599, Musashi left his village, apparently at the age of 15 (according to the Tosakushi, "the registry of the Sakushu region," although the Tanji Hokin hikki says he was 16 years old in 1599). His family possessions, furniture, weapons, genealogy, and other records were left with his sister and her husband, Hirao Yoemon. Musashi traveled around the country engaging in duels, such as one with an adept called Akiyama from the Tajima province. In 1600 a war began between the Toyotomi and Tokugawa. Musashi apparently fought on the side of the Toyotomi's "Army of the West," because the Shinmen clan (to which his family owed allegiance) had allied with them. He participated in the assault on Fushimi Castle in July 1600, in the defense of the besieged Gifu Castle in August of the same year, and finally in the famed Battle of Sekigahara. Some doubt has been cast on his participation in the final battle, as the Hyoho Senshi Denki has Musashi saying he is "no lord's vassal" and refusing to fight with his father (in Lord Ukita's battalion) in the battle. Omitting the Battle of Sekigahara from the list of Musashi's battles, however, would contradict the Go Rin no Sho's claim that Musashi fought in six battles.

The Army of the West lost decisively, and Shinmen Sokan fled to Kyushu province. It has been suggested that Musashi fled as well, and spent some time training on Mt. Hikosan. At the age of twenty, he arrived in Kyoto, where he began a famous series of duels against the Yoshioka School.

Musashi's father had defeated an adept of the Yoshioka School in his youth, receiving the title of "Best in Japan." The Yoshioka School (descended from either the Shinto ryu or the Kyo hachi ryu) was the foremost of the eight major schools of martial arts in Kyoto, the "Kyo ryu" or "schools of Kyoto." According to legend, these eight schools had been founded by eight monks taught by a mythical martial artist resident on the sacred mountain Kurama. At some point the Yoshioka family also began to make a name for itself not merely in the art of the sword but also in the textile business, for a special dye that they produced. They gave up teaching swordsmanship in 1614 when the Army of the West, of which they were a part, was defeated by Tokugawa Ieyasu, in the Battle of Osaka. In 1604, when Musashi began dueling them, they were still preeminent.

There are various accounts of the duels; the Yoshioka family documents claim that there was only one, against Yoshioka Kenpo, which Musashi lost. Musashi challenged Yoshioka Seijuro, master of the Yoshioka School, to a duel. Seijuro accepted, and they agreed to a duel outside Rendaji Temple on March 8, 1604. Musashi arrived late, greatly irritating Seijuro. They faced off, and Musashi struck a single blow, according to their agreement. This blow struck Seijuro on the left shoulder, knocking him out, and crippling his left arm. He apparently passed on the leadership of the school to his equally accomplished brother, Yoshioka Denshichiro, who promptly challenged Musashi to get revenge. The duel took place either outside Kyoto or in a temple called Sanjusangen-do. Denshichiro wielded a staff reinforced with steel rings (or possibly with a ball-and-chain attached), and Musashi arrived late a second time. Musashi disarmed Denshichiro and defeated him. This second victory outraged the Yoshioka clan, whose head was now the twelve-year-old Yoshioka Matashichiro. They assembled a force of archers and swordsmen, and challenged Musashi to a duel outside Kyoto, near Ichijoji temple. This time Musashi came to the temple hours early. From his hiding place Musashi ambushed the force, killing Matashichiro, and escaping under attack from dozens of his supporters. With the death of Matashichiro, that branch of the Yoshioka School was destroyed.

After Musashi left Kyoto, some sources recount that he traveled to Hozoin in Nara, to duel with and learn from the monks there, widely known as experts with lance weapons. There he settled down at Enkoji Temple in Banshu, where he taught the head monk (Tada Hanzaburo's brother). Hanzaburo's grandson would found the Ensu Ryu based on the Enmei Ryu teachings and iaijutsu (the art of drawing one’s sword).

From 1605 to 1612, Musashi traveled extensively all over Japan in Musha-Shugyo, a warrior pilgrimage during which he honed his skills with duels. In the duels of that era, the loser’s life was not taken unless it had previously agreed upon that the fight would end in death. Musashi was said to have used a bokken or bokuto (wooden sword) as his weapon, and such was his mastery of strategy that Musashi did not care which weapon his opponent was using.

A document dated November 5, 1607, purporting to be a transmission by Miyamoto Munisai of his teachings, suggests that Munisai lived at least until this date. In 1607, Musashi departed Nara for Edo, in the meanwhile dueling (and killing) a practitioner of kusari gama (a scythe and sickle with with a long iron chain and a weight connected to the end of the wooden handle) named Shishido Baiken. In Edo, Musashi defeated Muso Gonnosuke, who went on to found an influential staff school, the Shinto Muso Ryu. Musashi is said to have fought over 60 duels and was never defeated, although this is a conservative estimate, probably not accounting for deaths by his hand in major battles.

Duel with Sasaki Kojiro

In 1611, Musashi began practicing zazen (Zen meditation) at the Myoshinji Temple, where he met Nagaoka Sado, vassal to Lord Hosokawa Tadaoki (a powerful lord who had received the fief of northern Kyushu after the Battle of Sekigahara). Munisai had moved to northern Kyushu and became Tadaoki's teacher, and he may have introduced the two. Nagaoka proposed a duel with a certain adept named Sasaki Kojiro. This duel may have been politically motivated to consolidate Tadaoki's control over his fief.

On April 14, 1612, at the age of 28, Musashi had his most famous duel with Sasaki Kojiro, who wielded a nodachi (a type of long two-handed sword). Musashi came to the appointed place, the remote island of Funajima, north of Kyushu, late and unkempt. The duel was short and Musashi killed his opponent with a bokken that he had fashioned from an oar to be longer than the nodachi, an impressive feat by the standards of any samurai or swordsman. Musashi's late arrival is still a subject of controversy. Sasaki's outraged supporters thought it was dishonorable and disrespectful, while others thought it was a fair way to unnerve his opponent. Another theory is that Musashi timed the hour of his arrival to match the turning of the tide. The tide carried him to the island, and then turned by the time the fight ended. After his victory, Musashi immediately jumped back into his boat and his flight from Sasaki's vengeful allies was helped by the turning tide.

For centuries dramas and historical narratives featured this duel, and modern novels, movies, and comics have elaborated on the story of the duel of Funajima and called it “Ganryujima Duel.” Although this duel is part of folk history, several scholars say it lacks authenticity. The real name of Sasaki Kojiro is unknown, and nothing is known about his life.

Service

In 1614-1615, Musashi participated in the war between the Toyotomi and the Tokugawa clans. The war broke out because Ieyasu saw the Toyotomi family as a threat to his rule of Japan; most scholars believe that, as in the previous war, Musashi fought on the Toyotomi side. Osaka Castle was the center of the battle. The first battle (the Winter Battle of Osaka, Musashi's fourth battle) ended in a truce, and the second one (the Summer Battle of Osaka, Musashi's fifth battle in May 1615) resulted in the total defeat, of Toyotomi Hideyori's Army of the West by Ieyasu's Army of the East. Some reports even say that Musashi entered into a duel with Ieyasu, but was recruited to the Tokugawa side when Ieyasu sensed his own defeat was at hand. Although this seems unlikely, it is not known how Musashi came into Ieyasu's good graces after fighting on the side of his enemy.

Some accounts claim he actually served on the Tokugawa side. Such a claim is unproven, although Musashi had a close relationship with some Tokugawa vassals through his duel with Sasaki Kojiro. In his later years, Musashi received much support from Lords Ogasawara and Hosokawa, strong Tokugawa loyalists, casting doubt on the possibility that Musashi had indeed fought on behalf of the Toyotomis.

In 1615 he entered the service of Lord Ogasawara Tadanao of the Harima province as a foreman, or "Construction Supervisor," after having gained skills in construction. He helped to build Akashi Castle. He also adopted a son, Miyamoto Mikinosuke, and taught martial arts during his stay, specializing in the art of sword throwing, or shuriken.

In 1621 Musashi defeated Miyake Gunbei and three other adepts of the Togun Ryu in front of the Lord of Himeji; after this victory he helped to plan the layout of the Himeji Township. Around this time, Musashi attracted a number of disciples to his Enmei Ryu style. At the age of 22, Musashi had already written a scroll of Enmei Ryu teachings called Writings on the Sword Technique of the Enmei Ryu (Enmei Ryu Kenpo Sho). En meant "circle" or "perfection"; mei meant "light"/"clarity," and ryu meant "school"; the name seems to have been derived from the idea of holding the two swords up in the light so as to form a circle. The school's central focus was to train to use the twin swords of the samurai as effectively as a pair of sword and jitte.

In 1622, Musashi's adoptive son, Miyamoto Mikinosuke, became a vassal to the fief of Himeji. This may have prompted Musashi to embark on a new series of travels, ending in Edo (Tokyo) in 1623, where he became friends with Hayashi Razan, a prominent Confucian scholar. Musashi applied to become a sword master to the Shogun, but his application was denied because there were already two sword masters (Ono Jiroemon and Yagyu Munenori; the latter was a political advisor to the shogun and the head of the Shogunate's secret police). Musashi left Edo and traveled to Yamagata, where he adopted a second son, Miyamoto Iori. The two then traveled together, eventually stopping in Osaka.

In 1626, Miyamoto Mikinosuke, following the custom of junshi (death following the death of the lord), committed seppuku (ritual self-disembowelment) because of the death of his lord. In this year, Miyamoto Iori entered Lord Ogasawara's service. Musashi's attempt to become a vassal to the Lord of Owari, like other such attempts, failed.

Later Life and Death

In 1627 Musashi began to travel again. In 1633 he went to stay with Hosokawa Tadatoshi, daimyo (feudal lord) of Kumamoto Castle, who had moved to the Kumamoto fief and Kokura in order to train and paint. He settled in Kokura with Iori. While there he engaged in very few duels; one in which Musashi defeated a lance specialist, Takada Matabei, occurred in 1634 by the arrangement of Lord Ogasawara. He later entered the service of daimyo Ogasawara Tadazane, taking a major role in the Shimabara Rebellion in 1637. In his sixth and final battle, Musashi supported his son Iori and Lord Ogasawara as a strategist, directing their troops. Iori served with excellence in putting down the rebellion and gradually rose to the rank of karo, a position equal to a minister.

In the second month of 1641, Musashi wrote a work called the Hyoho Sanju Go ("Thirty-five Instructions on Strategy") for Hosokawa Tadatoshi; this work formed the basis for the later Go Rin no Sho (The Book of Five Rings). In the same year his third son, Hirao Yoemon, became Master of Arms for the Owari fief. In 1642, Musashi suffered attacks of neuralgia, foreshadowing his future ill-health. In 1643 he retired to a cave named Reigandō as a hermit to write Go Rin No Sho. He finished it in the second month of 1645. On May 12, sensing his impending death, Musashi bequeathed his worldly possessions, after giving his manuscript copy of the Go Rin No Sho to the younger brother of his closest disciple, Terao Magonojo. He died in Reigandō cave around May 19, 1645 (others say June 13). The Hyoho senshi denki described his passing:

At the moment of his death, he had himself raised up. He had his belt tightened and his wakizashi put in it. He seated himself with one knee vertically raised, holding the sword with his left hand and a cane in his right hand. He died in this posture, at the age of sixty-two. The principal vassals of Lord Hosokawa and the other officers gathered, and they painstakingly carried out the ceremony. Then they set up a tomb on Mount Iwato on the order of the lord.

Musashi was not killed in combat, but died peacefully after finishing the Dokkodo ("The Way of Walking Alone" or "The Way of Self-Reliance"), twenty-one precepts on self-discipline to guide future generations. His body was interred in armor in the village of Yuge, near the main road near Mount Iwato, facing the direction the Hosokawas would travel to Edo; his hair was buried on Mount Iwato itself. Nine years later, a monument with a funereal eulogy for Musashi, the Kokura hibun, was erected in Kokura by Miyamoto Iori.

Legends

After his death, various legends began to spread about Musashi. Most are about his feats in swordsmanship and other martial arts, some describing how he was able to hurl men over five feet backwards, others about his speed and technique. Legends tell of how Musashi killed giant lizards in Echizen prefecture, as well as nues (a legendary creature with the head of a monkey, the body of a raccoon-dog, and the legs of a tiger) in various other prefectures. He gained the stature of Kensei, a "sword saint," for his mastery in swordsmanship. Some believed he could run at super-human speed, walk on air, water and even fly through the clouds.

Philosophy and Background

Musashi’s way of life and his philosophy are relevant even in today’s world, and his book is popular with businessmen in Japan and has been translated into several languages. In a modern and democratic world, Musashi’s manual on military strategy and swordsmanship is a best seller.

Musashi lived just at the end of the Age of Civil Wars and the beginning of the Edo age, when the Tokugawa ruled all of Japan, peacefully and with cunning, for three hundred years. When Tokugawa’s last enemy, the Toyotomi clan, was eliminated by Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Siege of Osaka, a new era named “Genna” was ushered in, fueled by the desire of the rulers and most of the people to build a peaceful country. It meant the abandonment of arms and warfare. In the midst of this time of peace Musashi spoke of battle strategy and military philosophy. As knowledge of fighting tactics and strategy became less useful in actual life, the spirit of a martial artist like Musashi became valuable to the samurai in establishing their self-identity. Musashi’s spirit of swordsmanship and strong stoic moral teachings, rather than his practical techniques, were important. The samurai (warriors) began to form a stable government and occupy the top class of a hierarchy that was ordered from top to bottom into four divisions: samurai, farmers, artisans and tradesmen. The samurai class needed military tradition to ensure their survival and keep their identity. Miyamoto Musashi and his books were hailed among the feudal lords. The need to live in readiness to for battle had passed, and the samurai and feudal lords felt nostalgic for the barbarous force of the past. Miyamoto Musashi was a symbol of the old samurai spirit. Ironically the real Musashi was anti-establishment and anti-shogunate his entire life. Musashi’s life was glorified and romanticized and featured as the subject of numerous theatrical dramas and novels.

In his last work, the Dokkodo ("The Way of Walking Alone" or "The Way of Self-Reliance"), Musashi summarized his ethical views in twenty-one precepts. It expresses his strong Stoic spirit of self-discipline.

The Book of Five Rings

In Go Rin No Sho (五輪の書, The Book of Five Rings), whose subject was “pragmatism at the risk of life,” Musashi said that he fought 60 duels undefeated. He was a religious man, but he insisted that he respected the gods and Buddha without relying upon them. In the introduction of the Book of Five Rings, Mushashi suggested that he was never defeated because of his natural ability, or the order of heaven, or because the strategy of other schools was inferior. Musashi also insisted that he never quoted the law of Buddha or the teaching of Confucius, or any old war chronicles or books on martial tactics. He spoke only of what he himself had learned from his experiences on the battlefield and in duels.

The book was composed of four volumes, and is no longer in existence in its original form. It was a textbook on battle strategy and an instruction manual for actual warfare, not a book on philosophy and instruction for life. However, the book offers something of value for every person.

Volume I: The Ground Book

This volume talks about the tactics and the strategy of military affairs and of individual swordsmanship. Musashi seems to take a very philosophical approach to the "Craft of War": "There are four Ways in which men pass through life: as Gentlemen Warriors, Farmers, Artisans and Merchants." These categories were the groups of professionals that could be observed during Musashi's time. Throughout the book, Musashi employs the terms “Way of the Warrior,” and "true strategist" to refer to somebody who has mastered many art forms apart from those of the sword, such as tea ceremony, painting, laboring and writing, such as Musashi practiced throughout his life. Musashi was hailed as an extraordinary sumi-e (brush painting) artist in the use of ink monochrome, evident in two of his famous paintings: Shrike Perched in a Dead Tree (Koboku Meikakuzu, 古木明確図) and Wild Geese Among Reeds (Rozanzu, 魯山図). He makes particular note of artisans, and construction foremen. In the time in which he was writing, the majority of the houses in Japan were made of wood. In building a house, a foreman had to employ strategy based upon the skill and ability of his workers. Musashi suggested that the ideal foreman should know the strengths and weaknesses of his men, and not presume to make unfair demands of them.

In comparison to warriors and soldiers, Musashi notes the ways in which the artisan thrives through certain circumstances; the ruin of houses, the customers’ desires for splendor and luxury, changes in the architectural style of houses, the tradition and name or origin of a house. These are similar to the circumstances in which warriors and soldiers thrive; the rise and fall of prefectures and countries, and other political events create a need for warriors. The book also includes literal comparisons such as, "The carpenter uses a master plan of the building, and the Way of Strategy is similar in that there is a plan of campaign.”

Volume II: The Water Book

In this volume Musashi explains about understanding of the initial charge and one-on-one combat. Musashi asserted that, “Both in fighting and in everyday life you should be determined through calm (tranquility).” The purpose of self-possession is not to preserve one’s equanimity, but to be able to fight to the utmost. It is significant that Musashi strongly explained “Spiritual bearing in strategy” before explaining “Holding the long sword.”

Volume III: The Fire Book

In this volume Musashi explains the essence of how to get victory in battle. He writes, “In this Fire Book of the Ni To Ichi school of strategy, I describe fighting as fire.”

This book is often quoted in modern books on business strategy and personal improvement. Mushashi’s explanations, gained from his actual fighting experiences, can be applied in many circumstances.

To hold down a pillow

This means not allowing the enemy’s head to rise. Whatever action the enemy tries to initiate in the fight, you will recognize it in advance and suppress it.

Crossing at a ford

This description is exquisite. It means crossing the sea at a strait, or crossing over a hundred miles of broad sea at a crossing place. A good captain knows how to cross a sea route and he knows if his troops are almost across the strait or not. Musashi said “crossing at a ford” occurs often in a man’s lifetime. Crossing at a ford in our life means overcoming a critical moment. We often face “crossing at a ford”; however, we are unable to recognize the crucial moment. A master of the martial arts like Musashi can detect this moment. The Book of Five Rings summarizes “crossing at a ford” in two principles: know the times, meaning to know the enemy’s disposition; and “tread down the sword,” meaning to tread with body, tread with the spirit and to cut with a long sword, in other words, to preempt the action of your enemy.

Volume IV: The Wind Book

In this volume Musashi emphasizes the supremacy of Nitenichi-ryu style over other styles.

Volume V: The Book of the Void

The “void” is the goal of ascetic Buddhist practice, especially as taught by the second Buddha, Nāgārjuna, founder of the Middle Path school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Musashi says that people in this world look at things in error, and think that what they do not understand must be the void. This is not the true void. It is bewilderment.

Although Musashi talked of the “void,” he meant something different from the Buddhist “void.” Musashi’s void referred to the true way of strategy as a warrior.

Musashi used the metaphor of a flower and a nut for the learning of strategy, with the nut being the student and the flower being the technique. He was concerned that both teachers and students placed too much emphasis on technique and style and not enough on developing the maturity of the student. "In this kind of Way of Strategy, both those teaching and those learning the way are concerned with coloring and showing off their technique, trying to hasten the bloom of the flower." He emphasized that the ultimate goal was the development of the inner self.

"Men who study in this way think they are training the body and spirit, but it is an obstacle to the true Way, and its bad influence remains forever. Thus the true Way of strategy is becoming decadent and dying out." Musashi also said that one person who had mastered strategy could defeat an army.

"Just as one man can beat ten, so a hundred men can beat a thousand, and a thousand can beat ten thousand. In my strategy, one man is the same as ten thousand, so this strategy is the complete warrior's craft."

Ni-Ten Ichi Ryu and Mastery of the Long Sword

Musashi created and perfected a two-sword technique called “niten'ichi” (二天一, "two heavens as one") or “nitōichi” (二刀一, "two swords as one") or Ni-Ten Ichi Ryu (A Kongen Buddhist Sutra refers to the two heavens as the two guardians of Buddha). In this technique, the swordsman uses both a large sword, and a "companion sword" at the same time, such as a katana and wakizashi.

Legend says that Musashi was inspired by the two-handed movements of temple drummers, or by a European duel with rapier and dagger that he witnessed in Nagasaki. From his own writings, it seems that the technique came about naturally during battle, or developed from jitte (a short metal tuncheon) techniques which were taught to him by his father. The jitte was often used in battle paired with a sword; the jitte would parry and neutralize the weapon of the enemy while the sword struck or the practitioner grappled with the enemy. In his time a long sword in the left hand was referred to as gyaku nito. Today Musashi's style of swordsmanship is known as Hyōhō Niten Ichi-ryū.

Musashi disagreed with using two hands to wield a sword, because this limited freedom of movement and because a warrior on horseback often needed one hand to control the horse in crowds or on unstable ground. "If you hold a sword with both hands, it is difficult to wield it freely to left and right, so my method is to carry the sword in one hand.”

The strategy of the long sword was more straightforward. Musashi's ideal was to master a two-finger grip of the long sword, and use that to move on to the mastery of Ni-Ten Ichi Ryu. Though the grip is light, it does not mean that the attack or slash from the sword will be weak. "If you try to wield the long sword quickly you will mistake the Way. To wield the long sword well you must wield it calmly. If you try to wield it quickly, like a folding fan or a short sword, you will err by using ‘short sword chopping.’ You cannot cut down a man with a long sword using this method."

As in most disciplines in martial arts, Musashi notes that the movement of the sword after the cut is made must not be superfluous; instead of quickly returning to a stance or position, one should allow the sword to come to the end of its path from the force used. In this manner, the technique will become free-flowing, as opposed to abrupt; this principle is also taught in Tai Chi Ch'uan.

Musashi was also an expert in throwing weapons. He frequently threw his short sword, and Kenji Tokitsu believes that shuriken (throwing knife) methods for the wakizashi (accompanying sword) were the Niten Ichi Ryu's secret techniques.

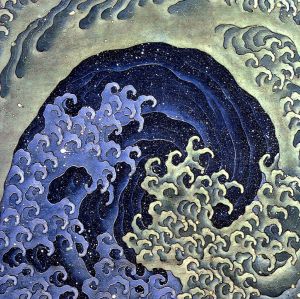

Musashi as an Artist

In his later years, Musashi claimed in his Go Rin no Sho that, "When I apply the principle of strategy to the ways of different arts and crafts, I no longer have need for a teacher in any domain." He proved this by creating recognized masterpieces of calligraphy and classic ink painting. His paintings are characterized by skilled use of ink washes and an economy of brush stroke. He especially mastered the "broken ink" school of landscapes, applying it to other subjects, such as his Koboku meikakuzu (Kingfisher Perched on a Withered Branch; part of a triptych whose other two members were Hotei Walking and Sparrow on Bamboo), his Hotei Watching a Cockfight, and his Rozanzu (Wild Geese Among Reeds).

Miyamoto Musashi in fiction

There have been thirty six films, including six with the title of Miyamoto Musashi, and a television series made about Musashi's life. Even in Musashi's time there were fictional texts about him resembling comic books. It is therefore difficult to separate fact from fiction when discussing Musashi.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Musashi, Miamoto and Thomas Cleary. The Book of Five Rings. Shambhala, 2005.

- Tokitsu, Kenji. Miyamoto Musashi: His Life and Writings. Shambhala, 2004.

- Wilson, William Scott. The Lone Samurai. Kodansha International, 2004.

- Carroll, John. Lightning in the Void: The Authentic History of Miyamoto Musashi. Printed Matter Press, 2006.

- Kaufman, Stephen K. Musashi's Book of Five Rings: The Definitive Interpretation of Miyamoto Musashi's Classic Book of Strategy. Tuttle Publishing; 2nd edition, 2004.

External links

All links retrieved October 11, 2018.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.