Miriam

Miriam (מִרְיָם, Miryam—"wished for child," "bitter" or "rebellious") was the sister of Moses and Aaron, and the daughter of Amram and Jochebed. She appears first in the book of Exodus in the Hebrew Bible. Her name could also be derived from the Egyptian words myr "beloved" or mr "love."

Miriam helped the infant Moses to be nursed by his own mother after being adopted by the daughter of Pharoah and later went on to become a prophetess in her own right. She led the Israelite women in celebrating the Israelite's successful march through the sea, in which Pharoah's horsemen were trapped, in a verse still sung by countless Jews. However, she and Aaron criticized Moses for marrying a Cushite woman, on grounds that they too were prophets. For this she was punished by God with a dreaded skin disease. Upon her death many years later, the Israelites mourned deeply and soon lost faith in Moses and Aaron, cause Moses himself to sin by striking the Rock at Kadesh.

Miriam is the only woman in history known to have been allowed to enter the sacred tent in which the Ark of the Covenant was housed. She was honored in verse by the prophet Micah, who placed her on a par with Moses and Aaron, and her name was particularly popular in New Testament times, where it is rendered as "Mary."

Bibiclical Narrative

Childhood

It was Miriam who, at Jochebed's request, followed as Moses (then a baby) floated down the Nile in a reed basket to evade the Pharaoh's order that newborn Hebrew boys be killed. She watched as the Pharaoh's daughter discovered the infant. "Shall I go and get one of the Hebrew women to nurse the baby for you?" Miriam asked the princess. (Ex. 2:7) Miriam returned with Jochebed. Pharaoh's daughter sent the child home with the "nurse," who raised him until he was weaned and "grew older." As a result of Miriam's act, Moses could be raised to identify with his background as a Hebrew, as well as his new role as an Egtyptian prince. (Exodus 2:1-10)

Prophetess and leader

Miriam does not appear again in the text until the time of the Exodus. She is called a prophetess, and composes a victory song after Pharaoh's army is drowned in persuit of the Israelites. She plays a central role in leading the Israelite women:

- When Pharaoh's horses, chariots and horsemen went into the sea, the Lord brought the waters of the sea back over them, but the Israelites walked through the sea on dry ground. Then Miriam the prophetess, Aaron's sister, took a tambourine in her hand, and all the women followed her, with tambourines and dancing. Miriam sang to them:

- "Sing to the Lord,

- for he is highly exalted.

- The horse and its rider

- he has hurled into the sea." (Exodus 15:20-21)

This short verse is considered by scholars to be one of the oldest in the Bible and is also celebrated in Jewish liturgy and folk music to this day.

Miriam and Aaron's sin

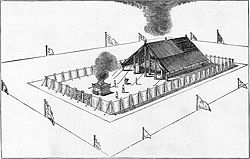

Later, Miriam objects to the marriage of Moses to a Cushite woman. She and Aaron discuss the matter with Moses in the Tent of Meeting, the sacred structure in which was housed the holy Ark of the Covenant. No other woman is recorded as having the privilege of entering this sacred space. Indeed, both the larger Tabernacle and the inner courts of the later Temple of Jerusalem were strictly out of bounds for women.

However, Miriam and Aaron have presumed too much. Standing at the entrace of the tent in a pillar of cloud, God speaks to tell them that while they may indeed be prophets, Moses' authority is higher than theirs. To Moses alone does God speak "face to face." To punish her, God stikes Miriam with a disease making her skin white and putrid, possibly in retaliation for her objections to the Cushite woman, who was likely dark-skinned. After Aaron asks Moses to intercede for Miriam, Moses utters a five-word prayer: El nah refa nah-la—"O El make her well."

He requires her to be confined outside the camp for seven days, after which she recovers. (Numbers 12). Aaron, however, is not punished, perhaps because a skin disease of this nature would disqualify him from the priesthood. The text implies the importance of Miriam to the community in noting: "the people did not move on till she was brought back." (Num. 12:15)

Death

Miriam dies and is buried at Kadesh and a great old age of more than 120 years. Her death apparently affects the Israelites deeply. Their internal longing for Miriam as a mother-figure is parallelled by the external thirst they experience for lack of water and this encampment. Moses, too, may have been affected by the loss of his sister. Commanded by God to "speak" to a rock and bring forth water for the people, Moses instead loses his temper, denounces the people and stikes the rock twice. Water is indeed produced, but God punishes both Moses and Aaron for Moses' striking the rock instead of speaking to it, telling them that they will not be allowed to enter the Promised Land of Canaan as a result.

Legacy

A passage in Micah suggests Miriam had a legacy with significant regard among later prophets:

- And I brought you forth out of the land of Egypt, and redeemed you from the house of bondage, and I set before you Moses, and Aaron, and Miriam." Micah 6:4)

In New Testament times, Miriam was perhaps the most popular name for Jewish woman. The Greek rendering of Miriam is "Mary." At least three important people in Jesus' life were named Miriam: his mother Mary, his best known female disciple Mary Magdalene, and Mary of Bethany, the sister of Martha and Lazarus who washed and anointed Jesus shortly before his death.

Today, Miriam is a popular figure among some Jewish feminists. Some place a "Cup of Miriam," filled with water, beside the customary "Cup of Elijah" (filled with wine) during the Passover Seder. The cup contains water in memory of Miriam's well, which according to a Midrash accompanied the Israelites on their journey through the desert. At Passover, some Modern Orthodox Jews have revived a millennium-old custom of adding a piece of fish to the seder plate, with the lamb, egg and fish jointly symbolizing the three prophets—Moses, Aaron, and Mary—referred to in Micah 6:4. This food also alludes to the mythical beasts: (the bird Ziz, the animal Behemoth, and the sea-creature Leviathan) which, according to Jewish legend, are to be served at the feast for the righteous following the resurrection of the dead.[1]

Rabbinical tradition

In praise of Miriam

Miriam is greatly lauded by the rabbis.

The Talmud preserves a tradition that it was the girl Miriam who convinced her parents to have more children despite the Pharoah's decree to kill the firstborn of the Israelites. Thus, without Miriam, there would have been no Moses, and no Exdous. Following Micah, the Talmud places Miriam on a par with Moses and Aaron in leadership: "There were three excellent leaders for Israel. They were Moses, Aaron and Miriam." While Moses and Aaron were leaders for all the people, "Miriam was the teacher of the women." (Taanit 9; Targum Micha 6:4)

Seeing the suffering of her people in slavery, Miriam wept bitterly. She praying unceasingly, and hoped for a better future. No one knew the bitterness of Egypt more than Miriam. The great medieval Jewish sage Rashi taught the young Miriam assisted her mother as a midwife and was particularly skilled in calming newborns and infants with her soothing voice. (Rashi on Exodus 1:15) Moreover, Miriam bravely righteous indignation when, just a girl of five, she encountered the Pharaoh, saying: "Woe to this man, when God avenges him!" (Midrash Rabbah, Shemot 1:13)

Rashi also taught that when Miram led the women in their victory song, their singing was more profound than that of the men, for the women not only sang, but also played their tambourines and danced. Thus, the women's hearts filled with joy than were the men's. (Rashi on Ex. 15:20)

Moreover, Miriam's death was directly connected to the lack of water at Kadesh. Her merit was so great that a well there, hidden under the infamous rock, dried up when Miriam the prophetess died. Rashi further taught that, just as the manna fell from heaven because of the merit of Moses and the Cloud of Glory enveloped the Israelites because of the merit of Aaron, the life-giving water was due to the merit of Miriam. [1]

Miriam's sin

The rabbis knew that no human being was without sin. Even Moses sinned, and Aaron, so of course Mirian too sinned, togther with Aaron, in the matter of Moses' marriage to the Cushite woman. Miriam's skin was turned white because she criticized Moses for marrying a black woman. But why was she punished, an not Aaron? According to the Leviticus 13, anyone with a skin disease was disqualified from the high priesthood. The Talmud thus notes that if Aaron had been punished as well as his sister, he would no longer have been able to perform his duties.

A separate question regards the identity of Moses' Cushite wife. Zipporah is identified as the wife of Moses, so the traditional Jewish and Christian view is that Zipporah is the wife in question. However, Zipporah is described as being a Midianite. According to Richard E. Friedman, because Cush refers to Ethiopia or other lands well outside, the "Cushite woman" of the story is not Zipporah. Friedman, building on interpretations from the documentary hypothesis, notes that Zipporah is only mentioned in the Yahwist text, ("J"), while the story of the Cushite woman is assigned to the Elohist.[2]

According to Friedman's interpretation, shared by several other scholars, these two accounts reflect the stories of two rival priesthoods, the Aaronic priesthood in the Kingdom of Judah, which claimed descent from Aaron and which controlled the Temple in Jerusalem, and a priesthood based at Shiloh, in the northern Kingdom of Israel. According to Friedman, the Elohist supported the Shiloh priesthood, and thus had a strong motivation to repeat this story, which is aimed not so much at Miriam as at Aaron. It is also the Elohist who tells the story of Aaron's creating the Golden Calf, while the Yahwist does not mention the incident.[3]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Winston, Pinchas, "The Point of No Discern" www.neveh.org. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ↑ Richard E. Friedman (May 1997). Who Wrote the Bible?. San Francisco: Harper, 78,92. ISBN 0-06-063035-3.

- ↑ ibid., pp. 76-77

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.