Livonian War

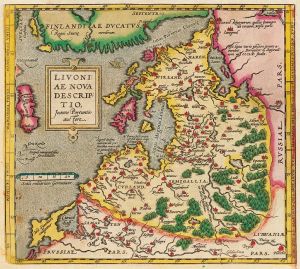

The Livonian War of 1558–1582 was a lengthy military conflict between the Tsardom of Russia and various coalitions of Denmark, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Kingdom of Poland (later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth), and Sweden for control of Greater Livonia (the territory of the present-day Estonia and Latvia). The Livonian War became a frontier conflict between two zones, the Scandinavian and the Russian, with the people of the Baltic caught in the middle. At its roots, it was a war about resources, about access to the sea for trade and strategic purposes. When the war began, Livonia was ruled by Germans. When it ended, most of Livonia was under the Union of Poland and Lithuania. After another war, it fell to Russia in 1721.

Dispute about access to or possession of valuable resources causes many conflicts. Wars will continue to wage around resources until mechanisms are developed to ensure their more equitable distribution across the globe; people need to recognize that the world is a common home. It has to sustain all life-forms, while remaining healthy and viable itself. Ultimately, the type of alliance of interests that the defeated Livonian Confederation represented, might be indicative of how human society ought to evolve, towards a trans-national form of governance.

Background

By the late 1550s, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation had caused internal conflicts in the Livonian Confederation, a loose alliance in what is now Estonia and Latvia led by the Livonian Order of the Teutonic Knights. The knights were formed in 1237, the Confederacy in 1418.[1] Originally allied with the Roman Catholic Church, Lutheranism was now increasingly popular and some of the knights were "estranged from the Catholic bishops."[2] Since the Confederacy was an alliance between some free cities, the bishops and the Knights, this seriously weakened its ability to respond to a military threat. This area of the Baltic had always attracted the interest of other powers, anxious to benefit from sea trade and to develop naval capabilities. Meanwhile, the Confederacies Eastern neighbor Russia had grown stronger after defeating the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan. The conflict between Russia and the Western powers was exacerbated by Russia's isolation from sea trade because of lack of access to the lucrative Baltic sea routes. Neither could the tsar easily hire qualified labor from Europe. Compared with the Khante, Livonia "appeared to be an easy target."[2]

In 1547, Hans Schlitte, the agent of Tsar Ivan IV, employed craftsmenin Germany for work in Russia. However all these handicraftsmen were arrested in Lübeck at the request of Livonia. The German Hanseatic League ignored the new port built by tsar Ivan on the eastern shore of the Narva River in 1550 and still delivered the goods still into ports owned by Livonia.

Outbreak of hostility

Tsar Ivan IV demanded that the Livonian Confederation pay 40,000 talers for the Bishopric of Dorpat, based on a claim that the territory had once been owned by the Russian Novgorod Republic. The dispute ended with a Russian invasion in 1558. Russian troops occupied Dorpat (Tartu) and Narwa (Narva), laying siege to Reval (Tallinn). The goal of Tsar Ivan was to gain vital access to the Baltic Sea.

Tsar Ivan's actions conflicted with the interests of other countries; they wanted both to block Russian expansion and to "obtain portions of Livonia for themselves." What began as a type of border dispute soon escalated into "a regional war."[3] On August 2, 1560, the Russians inflicted a defeat on the Knights, killing so many that the weakened was soon dissolved by the Vilnius Pact; its lands were assigned to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania united with Poland (Ducatus Ultradunensis), and the rest went to Sweden (Northern Estonia), and to Denmark (Ösel).[4] The last Master of the Order of Livonia, Gotthard Kettler, became the first ruler of the Polish and Lithuanian (later Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) vassal state Duchy of Courland.

Erik XIV of Sweden and Frederick II of Denmark then sent troops to protect their newly-acquired territories. In 1561, the city council of Reval surrendered to Sweden, and became the outpost for further Swedish conquests in the area. By 1562, Russia found itself in wars with both Lithuania and Sweden. In the beginning, the Tsar's armies scored several successes, taking Polotsk (1563) and Pernau (Pärnu) (1575), and overrunning much of Lithuania up to Vilnius, which led him to reject peace proposals from his enemies.

However the Tsar (called The Terrible) found himself in a difficult position by 1597 as the tide of battle began to turn.[5] The Crimean Tatars devastated Russian territories and burnt down Moscow (see Russo-Crimean Wars), the drought and epidemics have fatally affected the economy, and Oprichnina had thoroughly disrupted the government, while Lithuania had united with Poland (new union in 1569) and acquired an energetic leader, king Stefan Batory. Not only did Batory reconquer Polotsk (1579), but he also seized Russian fortresses at Sokol, Velizh, Usvzat, Velikie Luki (1580), where his soldiers massacred all Russian inhabitants, and laid siege to Pskov (1581–82). Polish-Lithuanian cavalry devastated the huge regions of Smolensk, Chernigov, Ryazan, southwest of the Novgorodian territory and even reached the Tsar's residences in Staritsa. Ivan prepared to fight, but the Poles retreated. In 1581, a mercenary army hired by Sweden and commanded by Pontus de la Gardie captured the strategic city of Narva and massacred its inhabitants, 7,000 people.[6] The Livonian War left Russia impoverished.[7]

These developments led to the signing of the peace Treaty of Jam Zapolski in 1582, between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in which Russia renounced its claims to Livonia.[8] The Jesuit papal legate Antonio Possevino was involved in negotiating that treaty. The following year, the Tsar also made peace with Sweden. Under the Treaty of Plussa, Russia lost Narva and the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland, being its only access to the Baltic Sea. The situation was partially reversed 12 years later, according to the Treaty of Tyavzino which concluded a new war between Sweden and Russia. From the Baltic perspective, the war "brought destruction, misery and new non-resident sovereigns."[9]

Legacy

The Baltic has seen many struggles between various powers to control the region, motivated by both commercial and strategic interest. The Baltic states of Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia have historically either fallen to Scandinavian or to Russian domination. After the Great Northern War (1700-1721) the Baltic passed back into Russian hands as Swedish "aspiration to dominion of the Baltic proved unsustainable."[10] Sweden had moved against an alliance of Russia, Poland-Lithuania and Saxony to claim supremacy in the Baltic. The result was that Russia occupied and claimed Livonia. What remained under Poland was annexed in 1772, when Poland was partitioned. Following World War I, the three states made a brief reappearance as sovereign nations but were invaded by the Soviet Union in World War II and did not gain independence again until 1991. In 2004, they joined the European Union and NATO.

The Livonian War, within the wider legacy of rivalry and competition in this region, is rooted in the desire of some to dominate others, to acquire resources, transport and communication opportunities of a strategic and economic advantage. Caught between powerful imperial polities on both sides, the people of the Baltic have struggled to govern themselves, to develop their distinct identities. The nation-state model of human political organization respects people's distinctive culture and traditions. On the other hand, nations more often than not act in self-interest. Self-rule does not necessarily represent the moral high ground; having been exploited by others does not make people, once free, any less inclined to assert their self-interest over others.

Many wars have been waged around access to the sea and around access to or possession of other resources. Resources will continue to be the cause of war or of international disputes until mechanisms are developed to ensure a more equitable distribution of these across the globe, recognizing that the world is humanity's common home. It has to sustain all people, all life-forms and remain viable. Ultimately, the type of alliance of interests that the defeated Livonian Confederation represented, might be indicative of how human society ought to evolve, towards a trans-national form of governance. On the one hand, the Livonian Confederation was run by Germans not by ethnic Estonians and Latvians; on the other hand, it was based on cooperative principles even if "cooperation and collaboration emerged only when their was an external threat and sometimes not even then."[11]

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Longworth, Philip. 2006. Russia: The Once and Future Empire from Pre-History to Putin. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312360412.

- Martin, Janet. 1995. Medieval Russia: 980-1584. Cambridge Medieval Textbooks. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521362764.

- O'Connor, Kevin. 2006. Culture and Customs of the Baltic States. Culture and customs of Europe. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313331251.

- Plakans, Andrejs. 1995. The Latvians: A Short History. Studies of Nationalities. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University. ISBN 9780415285803.

- Roberts, Michael. 1986. The Early Vasas: A History of Sweden 1523-1611. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521311823.

- Smith, David J. 2002. The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415285803.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.