Kuril Islands

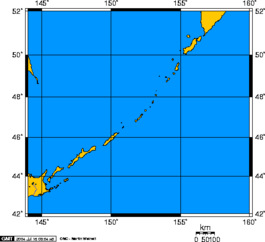

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands in Russia's Sakhalin Oblast region, are a volcanic island archipelago that stretches approximately 750 miles (1,300 km) northeast from Hokkaidō, Japan, to the Russian Kamchatka Peninsula, separating the Sea of Okhotsk on the west from the North Pacific Ocean on the east. The chain consists of 22 main islands (most of which are volcanically active) and 36 smaller islets with a total area of 6,000 square miles (15,600 km²).

The islands were explored by Russians in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, after which they began settlement. A group of the southern islands were seized by Japan in 1855, and 20 years later they laid claim to the entire chain. The islands were ceded to the Soviet Union in the 1945 Yalta agreements, after which the Japanese were repatriated and the islands repopulated by Soviets. The islands are still in dispute, with Japan and Russia continuously attempting renegotiation, but unable to come to an agreement.

Nomenclature

The Kuril Islands are known in Japanese as the Chishima Islands (literally Thousand Islands Archipelago) also known as the Kuriru Islands (literally Kuril Archipelago). The name Kuril originates from the autonym of the aboriginal Ainu: "kur," meaning man. It may also be related to names for other islands that have traditionally been inhabited by the Ainu people, such as Kuyi or Kuye for Sakhalin and Kai for Hokkaidō.

Geography

The Kuril Islands form part of the ring of tectonic instability encircling the Pacific Ocean referred to as the Pacific Ring of Fire. The islands themselves are summits of stratovolcanoes that are a direct result of the subduction of the Pacific Plate under the Okhotsk Plate, which forms the Kuril Trench some 200 km east of the islands.

The islands are divided into three sub-groups that are separated by deep (up to 2,000 m) straits: the Northern Kuril Islands (Shumshu to Shiashkotan) are separated from the Central Kuril Islands (Matua to Simushir) by the Krusentern Strait. The Central Kuril Islands are, in turn, separated from the Southern Kuril Islands (Chirpoy to Kunashir) by the Boussole Strait [1].

The chain has approximately 100 volcanoes, some 35 of which are active, and many hot springs and fumaroles. There is frequent seismic activity, including an earthquake of magnitude 8.3 recorded on November 15, 2006, which resulted in tsunami waves up to 5.77 ft reaching the California coast at Crescent City. The waves even reached almost 5 ft at Kahului, Hawaii, which shows the severity of the earthquake.[2] The November 15 earthquake is the largest earthquake to have occurred in the central Kuril Islands since the early twentieth century.

The climate on the islands is generally severe, with long, cold, stormy winters and short and notoriously foggy summers. The average annual precipitation is 30–40 inches (760–1,000 mm), most of which falls as snow which may occur from the end of September to the beginning of June. Winds often reach hurricane strength, at more than 40 miles per second.

The chain ranges from temperate to sub-arctic climate types, and the vegetative cover consequently ranges from tundra in the north to dense spruce and larch forests on the larger southern islands. The highest elevations on the island are Alaid Volcano (highest point 2339 m) on Atlasov Island at the northern end of the chain and the Sakhalin Region and Tyatya volcano (1819 m) on Kunashir Island at the southern end.

Landscape types and habitats on the island include many kinds of beach and rocky shores, cliffs, wide rivers and fast gravelly streams, forests, grasslands, alpine tundra, crater lakes and peat bogs. The soils are generally productive, due to the periodic influxes of volcanic ash and, in certain places, due to significant enrichment by seabird excrements and higher levels of sea salt. However, many of the steep, unconsolidated slopes are susceptible to landslides and newer volcanic activity can entirely denude a landscape.

Marine ecology

Due to their location along the Pacific shelf edge and the confluence of Okhotsk Sea gyre and the southward Oyashio current, the waters around the Kuril islands are among the most productive in the North Pacific, supporting a wide range and high abundance of marine life.

Invertebrates: Extensive kelp beds surrounding almost every island provide crucial habitat for sea urchins, various mollusks, crab, shrimp, sea slugs, and countless other invertebrates and their associated predators. Many species of squid provide a principle component of the diet of many of the smaller marine mammals and birds along the chain.

Fish: Further offshore, walleye pollock, Pacific cod, mackerel, flounder, sardines, tuna, and several species of flatfish are of the greatest commercial importance. During the 1980's, migratory Japanese sardine was one of the most abundant fish in the summer and the main commercial species, but the fishery collapsed and by 1993 no sardines were reported caught, leading to significant economic contraction in the few settlements on the islands. At the same time, the pink salmon population increased in size, although it is not believed that they were direct competitors with each other. Several salmon species, notably pink and sockeye, spawn on some of the larger islands and local rivers. In the southern region, lake minnow, pacific redfin, and bleeker fish could be found as well.

Pinnipeds: The Kuril islands are home to two species of eared seal, the Steller sea lion and northern fur seal, both of which aggregate on several smaller islands along the chain in the summer to form several of the largest reproductive rookeries in Russia. Most of the estimated 5,500 pinnipeds inhabiting the southern Kurile Islands-Hokkaido region are currently concentrated in the waters around Kunashir and the Small Kurile Chain where their main rookeries, habitats, and breeding grounds are found [3]. A distinct Kuril island subspecies of the harbor seal (Phoca vitulina Kurilensis), a subspecies of sea otter (Enhydra lutris kurilensis) and Largha are also abundant.

Pinnipeds were a significant object of harvest for the indigenous populations of the Kuril islands, both for food and materials such as skin and bone. The long term fluctuations in the range and distribution of human settlements along the Kuril island presumably tracked the pinniped ranges. In historical times, fur seals were heavily exploited for their fur in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and several of the largest reproductive rookeries, as on Raykoke Island, were extirpated. However, sea otters seem to have disappeared prior to commercial hunting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as no records could be found documenting the hunting of otters around Hokkaido during that period [4]. Since the 1960s there has been essentially no additional harvest and the pinniped populations in the Kuril islands appear to be fairly healthy and in some cases expanding. Due to increasing anthropogenic habitat disturbance, it is unlikely that a stable habitat for sea otters can be established on the coastal waters or Hokkaido [5]. The notable example is the now extinct Japanese Sea Lion which was known to occasionally seen on the Kuril islands.

Scientist from the United States, Japan and Russia (with financial support provided by the National Marine Mammal Laboratory, Alaska Sealife Center, and Amway Nature Center, Japan) conducted a survey which completed in July of 2001 to collect biological data on the distribution of the sea lions on the Kuril and Iony Islands. A total of 4,897 Steller sea lions age 1+ years old and 1,896 pups were counted on all rookeries in the Kuril Islands [6].

Sea otters were exploited very heavily for their pelts in the nineteenth century, until such harvest was halted by an international treaty in 1911. Indeed, the pursuit of the valuable otter pelts drove the expansion of the Russians onto the islands and much of the Japanese interest. Their numbers consequently dwindled rapidly. A near total ban on harvest since the early twentieth century has allowed the species to recover and they are now reasonably abundant throughout the chain, currently occupying approximately 75 percent of the original range.

Cetaceans: The most abundant of the whales, dolphins and porpoises in the Kuril Islands include orcas, bottlenose dolphins, Risso's dolphins, harbor and Dall's porpoises. Baird's, Bryde's, and Cuvier's beaked whales, killer whales, fin whales, and sperm whales are also observed.

Seabirds: The Kuril islands are home to many millions of seabirds, including northern fulmars, tufted puffins, murres, kittiwakes, guillemots, auklets, petrels, gulls, cormorants, and quail. On many of the smaller islands in summer, where terrestrial predators are absent, virtually every possibly hummock, cliff niche or undersie of boulder is occupied by a nesting bird. Birds with restricted range include the spotted redshank (Tringa erythropus), Japanese Robin (Erithacus akahige), Bull-headed Strike (Lanius bucephalus), and the Forest Wagtail (Motacilla lutea) [7].

Terrestrial ecology

The composition of terrestrial species on the Kuril islands is dominated by Asian mainland taxa via migration from Hokkaido and Sakhalin Islands and by Kamchatkan taxa from the North. While highly diverse, there is a relatively low level of endemism.

Because of the generally smaller size and isolation of the central islands, few major terrestrial mammals have colonized these, though Red and Arctic fox were introduced for the sake of the fur trade in the 1880s. The bulk of the terrestrial mammal biomass is taken up by rodents, many introduced in historical times. The largest southernmost and northernmost islands are inhabited by brown bear, fox, martens, and shrews. Some species of deer are found on the more southerly islands.

Among terrestrial birds, ravens, peregrine falcons, some wrens, wagtails, and Vestper bats are also common.

Islands

The second northernmost, Atlasov Island (Oyakoba to the Japanese), is an almost perfect volcanic cone rising sheer out of the sea, and has led to many Japanese tributes in such forms as haiku and wood-block prints, extolling its beauty, much as they do the more well-known Mount Fuji. It contains the highest points of the chain.

While in Russian sources the islands are mentioned for the first time in 1646, the earliest detailed information about them was provided by the explorer Vladimir Atlasov in 1697. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the Kuril Islands were explored by Danila Antsiferov, I. Kozyrevsky, Ivan Yevreinov, Fyodor Luzhin, Martin Shpanberg, Adam Johann von Krusenstern, Vasily Golovnin, and Henry James Snow.

From north to south, the main islands are (alternative names given in parentheses are mainly Japanese):

- Shumshu (Shimushu)

- Atlasov Island (Oyakoba, Alaid or Araito)

- Paramushir (Paramushiro or Poromushiri)

- Antsiferov Island (Shirinki)

- Makanrushi (Makanrushiri)

- Onekotan (Onnekotan)

- Kharimkotan (Kharimukotan, Harumokotan)

- Ekarma (Ekaruma)

- Chirinkotan (Chirinkotan)

- Shiashkotan (Shashukotan)

- Raikoke (Raykoke)

- Matua (Matsuwa)

- Rasshua (Rasuwa, Rashowa)

- Ushishir (Ushishiri, Ushichi)

- Ketoy (Ketoe, Ketoi)

- Simushir (Shimushiro, Shinshiru)

- Broutona (Buroton, Makanruru)

- Chirpoy (Chirinhoi, Kita-jima)

- Brat Chirpoyev (Burato-Chiripoi)

- Urup (Uruppu)

- Iturup (Etorofu)

- Kunashir (Kunashiri)

- And the Lesser Kurils:

- Shikotan

- Habomai Rocks, including Seleni (Shibotsu), Taraku, Yuri, Akiyuri, Suisho, Zelioni (Kaigara), Oodoke and Moeshiri

- Volcanoes in Kurils islands:

- Shimanobore (Kunashiri)

- Cha-Cha (volcano) (Kunashiri)

- Nishi-Hitokkapu (Etorofu)

- Moyoro (Etorofu)

- Atatsunobore (Uruppu)

- Shimushiri Fuji (Shimushiro)

- Matsuwa (Matsuwa)

- Onnekotan (Onnekotan)

- Kharimukotan (Kharimukhotan)

- Suribachi (Paramushiro)

- Eboko (Paramushiro)

- Fuss (Paramushiro)

- Chikurachiki (Paramushiro)

- Shumushu (Shumushu)

- Araito (Araito)

History

The Kuril Islands first came under Japanese administration in the fifteenth century during the early Edo period of Japan, in the form of claims by the Matsumae clan, and play an important role in the development of the islands. It is believed that the Japanese knew of the northern islands 370 years ago, [8] as the initial explorations were of the southernmost parts of the islands. However, trade between these islands and Ezo (Hokkaidō) existed long before then. On "Shōhō Onkuko Ezu," a map of Japan made by the Tokugawa shogunate, in 1644, there are 39 large and small islands shown northeast of the Shiretoko peninsula and Cape Nosappu. In 1698 V. Atlasov discovered the island which was later named in his honor.

Russia began to advance into the Kurils in the early eighteenth century. Although the Russians often sent expedition parties for research and hunted sea otters, they never went south of Uruppu island. This was because the Edo Shogunate controlled islands south of Etorofu and had guards stationed on those islands to prevent incursions by foreigners. In 1738-1739 M. Shpanberg had mapped Kuril Islands for the first time and S. Krasheninnikov had written a description of the nature found there.

In 1811, Captain Golovnin and his crew, who stopped at Kunashir during their hydrographic survey, were captured by retainers of the Nambu clan, and sent to the Matsumae authorities. Because a Japanese seaman, Takataya Kahei, was also captured by a Russian vessel near Kunashiri, Japan and Russia entered into negotiations to establish the border between the two countries in 1813.

The Treaty of Commerce, Navigation and Delimitation was concluded in 1855, and the border was established between Etorofu and Uruppu. This border confirmed that Japanese territory stretched south from Etorofu and Russian territory stretched north of Uruppu. Sakhalin remained a place where people from both countries could live. In 1875, both parties signed the Treaty of Saint Petersburg, whereas Japan relinquished all its rights in Sakhalin in exchange for Russian cession of all its rights in the Kuriles to Japan.

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, Gunji, a retired Japanese military man and local settler in Shumshu, led an invading party to the Kamchatka coast. Russia sent reinforcements to the area to capture this coastal area. Following the war, Japan received fishing rights in Russian waters as part of the Russo-Japanese fisheries agreement until 1945.

During their armed intervention in Siberia 1918–1925, Japanese forces from the northern Kurils, along with United States and European forces, occupied southern Kamchatka. Japanese vessels made naval strikes against Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky.

The Soviet Union reclaimed the South of Sakhalin and the Kuriles by force at the end of World War II through the Treaty of San Francisco, but Japan maintains a claim to the four southernmost islands of Kunashir, Iturup, Shikotan, and the Habomai rocks, together called the Northern Territories.

Japanese Administration in Kuril Archipelago

In 1869, the new, Meiji government established the Colonization Commission in Sapporo to aid in the development of the northern area. Ezo was renamed Hokkaidō and Kita Ezo later received the name of Karafuto. Eleven provinces and 86 districts were founded by the Meiji government and were put under the control of feudal clans. With the establishment of prefectures instead of feudal domains in 1871, these areas were put under direct control of the Colonization Commission. Because the new Meiji government could not sufficiently cope with Russians moving to south Sakhalin, the Treaty for exchange of Sakhalin for the Kuril Island was concluded in 1875 and 18 islands to the north of Uruppu, which had belonged to Russia, were transferred to Japan.

Road networks and post offices were established on Kunashiri and Etorofu. Life on the islands became more stable when a regular sea route connecting islands with Hokkaidō was opened and a telegraphic system began. At the end of the Taisho era, towns and villages were organized in the northern territories and village offices were established on each island. The town and village system was not adopted on islands north of Uruppu, which were under direct control of Nemuro Subprefectural office of the Hokkaidō government.

Each village had a district forestry system, a marine product examination center, a salmon hatchery, a post office, a police station, elementary school, Shinto temple, and other public facilities. In 1930, 8,300 people lived on Kunashiri island and 6,000 on Etorofu island, most of whom were engaged in coastal and high sea fishing.

Kurils during World War II

On November 22, 1941, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku ordered the meeting of the Imperial Japanese Navy Strike force for the Attack on Pearl Harbor, in Tankan or Hittokappu Bay, in Etorofu Island in the South Kurils. The territory was chosen for its sparse population, lack of foreigners, and constant fog coverage. The Admiral ordered the move to Hawaii on the morning of November 26.

Japan increased their garrison in north Kurils from approximately 8,000 in 1943 to 41,000 in 1944 and maintained more than 400 aircraft in Kurils and Hokkaidō area in anticipation of a possible American invasion via Alaska.

From August 18 through 31, 1945, Soviet forces invaded the North and South Kurils. In response, the U.S. Eleventh Air Force, sent between August 24 and September 4, deployed two B-24 fighters in a reconnaissance mission over the North Kuril Islands to photograph the Soviet occupation in the area. They were intercepted and forced away, a foretaste of the Cold War that lay ahead.

Kuril Islands dispute

The Kuril Island dispute is a dispute between Japan and Russia over sovereignty of the four southernmost Kuril Islands. The disputed islands are currently under Russian administration as part of the Sakhalin Oblast, but are also claimed by Japan, which refers to them as the Northern Territories or Southern Chishima. The disputed islands are:

- Kunashiri in Russian (Кунашир) or Kunashiri in Japanese

- Iturup in Russian (Итуруп), or Etorofu in Japanese

- Shikotan in both Russian (Шикотан) and Japanese

- the Habomai rocks in both Russian (Хабомай) and Japanese

The dispute results from an ambiguity over the Treaty of San Francisco of 1951. Under Article 2c, Japan renounces all right, title, and claim to the Kuril Islands, and to that portion of Sakhalin, containing the ports of Dalian and Port Arthur, and the islands adjacent to it over which Japan acquired sovereignty as a consequence of the Treaty of Portsmouth which was signed on September 5, 1905. It was in accord with earlier agreements between the Allied powers and one of the conditions of the USSR to enter into war against Japan.

However, the Soviet Union chose not to be a signatory to the San Francisco Treaty. Article 2 of an earlier (1855) Russo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce, Navigation and Delimitation (the Treaty of Shimoda), which provided for an agreement on borders, states "Henceforth the boundary between the two nations shall lie between the islands of Etorofu and Uruppu. The whole of Etorofu shall belong to Japan; and the Kurile Islands, lying to the north of and including Uruppu, shall belong to Russia." Kunashiri, Shikotan and Habomais Islands are not explicitly mentioned in the treaty.

On October 19, 1956, the Japan-Soviet Joint Declaration was signed in place of a peace treaty, stipulating the termination of the state of war and the resumption of diplomatic relations. This Declaration was ratified by both countries and was registered with the United Nations as an international agreement. In Article 9 of the Declaration, the Soviet Union agreed that after normal diplomatic relations between the two countries had been re-established, the peace treaty negotiations would be continued and the Soviet Union would hand over Habomai and Shikotan Islands to Japan.

In October 1993, then-Prime Minister Morihiro Hosokawa and then-President Boris Yeltsin agreed that the guidelines of negotiations toward resolution would be: (a) based on historical and legal facts; (b) based on documents compiled with the agreement of the two countries; and (c) based on the principles of law and justice (Tokyo Declaration).

In March 2001, Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori visited Irkutsk. Prime Minister Mori and President Vladimir Putin confirmed the Japan-Soviet Joint Declaration signed in 1956 as a basic legal document, which sets a starting point for the negotiation process, and in addition confirmed that based on the 1993 Tokyo Declaration, a peace treaty should be concluded by resolving the issue of the attribution of the Four Islands (The Irkutsk Statement). Based on results achieved to date, including the Irkutsk Statement, both Japan and Russia are continuing to engage in vigorous negotiations to find the solution acceptable to both countries [9].

There was essentially no hostile activity between the USSR and Japan before the USSR renounced the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact that had been concluded on April 13, 1941, and Foreign Commissar Molotoff declared war on Japan (Operation August Storm) on August 8, 1945, arguing that Japan was “the only great power that still stood for the continuation of the war.” [10]. A day later, the Soviet army launched "a classic double envelopment of Japanese-occupied Manchuria. [11].

On July 7, 2005, the European Parliament issued an official statement recommending the return of the territories in dispute, to which Russia protested immediately. [12]

As of 2006, Russia's Putin administration has offered Japan the return of Shikotan and the Habomais (about 6 percent of the disputed area) if Japan renounce its claims to the other two islands, Kunashiri and Etorofu, which make up 93 percent of the total area of the four disputed islands. They have been held by Russia since the end of the war, when Soviet troops captured them. The Soviet-Japanese joint declaration of 1956 signed by both nations promised at least Shikotan and the Habomais be returned to Japan before a peace agreement could be made. [13]

On August 16, 2006, a Russian border patrol boat found a Japanese vessel illegally fishing for crab in Russian waters near the disputed islands. The Japanese vessel allegedly defied several orders to stop, and made dangerous maneuvers. A Russian patrol opened preventive fire on the Japanese vessel. A Japanese 35-year-old crab fisherman, Mitsuhiro Morita, [14] was wounded in the head unintentionally and died later, while three others were detained and questioned. It was the first fatality related to this dispute in since October of 1956. [15]. However, the diplomatic fallout from this incident was minimal [16], even if it does complicate the reconciliation of the two countries.

Demographics

Today, roughly 30,000 people (ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Tatars, Koreans, Nivkhs, Oroch, and Ainu) inhabit the Kuril Islands. About half of the population lives below the poverty line, according to the regional administration. Fishing is the primary occupation. The islands have strategic and economic value, in terms of fisheries and also mineral deposits of pyrite, sulfur, and various polymetallic ores.

Notes

- ↑ Kuril Islands, Kuril Islands. Retrieved April 18, 2007

- ↑ Magnitude 8.3 - Kuril Islands, U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ↑ McGinley, Mark. April 26, 2007. South Sakhalin-Kurile mixed forests, World Wildlife Fund in Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved May 17, 2007

- ↑ Mammal Study, Mammal Study. Retrieved May 18, 2007

- ↑ History and status of sea otters, Enhydra lutris along the coast of Hokkaido, Japan, BioOne. Retrieved May 18, 2007

- ↑ Steller Sea Lion Survey on Kuril and Iony Islands, Russia, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 14, 2007

- ↑ South Sakhalin-Kurile mixed forests, The Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved May 17, 2007

- ↑ John J. Stephan, The Kuril Islands; Russo-Japanese frontier in the Pacific (London: Oxford University Press, 1974, ISBN 9780198215639) 50-56.

- ↑ Overview of the Issue of the Northern Territories, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved May 18, 2007

- ↑ Brad Tytel. September 15, 2005. The Guns of August, The Guns of August. Russian-American Journalism Institute. Retrieved May 22, 2007

- ↑ Gilles Van Nederveen, Air & Space Power Journal (Fall, 2004) The Soviet Strategic Offensive in Manchuria, 1945, FindArticles.com. Retrieved May 22, 2007

- ↑ Relations between the EU, China and Taiwan and security in the Far East, European Parliament. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ↑ Kyodo News International. April 9, 2001. Putin told Mori Russia intends to return only 2 islands, FindArticles: LookSmart, Ltd. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ↑ TIME 168, e (10), 12. (August 28, 2006) "Milestones"

- ↑ Japan fisherman killed by Russia, BBC News, Retrieved May 22, 2007

- ↑ Russia-Japan Island Row Intensifies with Killing of Fisherman, Power and Interest News Report, Retrieved May 22, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bodkin, James L. Sea Otters in the North Pacific Ocean. Our Living Resources. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Burkanov, Vladimir N. Steller Sea Lion Survey on Kuril and Iony Islands, Russia. Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Stephan, John J. The Kuril Islands; Russo-Japanese frontier in the Pacific. London: Oxford University Press, 1974. ISBN 9780198215639

- International Kuril Island Project. University of Washington Fish Collection. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Japan. Bartleby, 2001-2005. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- August 21, 2006. 7TH LD: Japanese fisherman shot dead on boat by Russian border patrol. Look Smart. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Kuril Islands. Yahoo! Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- History and status of sea otters, Enhydra lutris along the coast of Hokkaido, Japan. BioOne. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Kuril Islands. Heritage Expeditions. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Joint Compendium of Documents on the History of Territorial Issue between Japan and Russia IV. SAN FRANCISCO PEACE TREATY. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 1951. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Japan's Northern Territories. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Variability of Pink Salmon Sizes in relation with abundance of Okhotsk Sea stocks. North Pacific Marine Science Organization. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Vysokov, Mikhail. A Brief History of Sakhalin and the Kurils. (in English) History. Includes detailed timeline. Sakhalin and Kuriles.

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2018.

- Kuril Island Biocomplexity Project. Kuril Island Biocomplexity Project.

- Japan's Northern Territories. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.