Israel Jacobson

Israel Jacobson (October 17, 1768 - September 14, 1828, Berlin) was a German-Jewish financier and philanthropist often considered as one of the fathers Reform Judaism.

Born in Halberstadt in today's Saxony-Anhalt, Germany, Jacobson married into the family of the wealthy court Jew Hertz Samson and later inherited his father-in-law's land and titles. He soon acquired important friends in the court of Frederick II of Prussia, developing great wealth and substantial influence.

A supporter of the Jewish Enlightenment, Jacobson worked to create cordial relations between Jews and Gentiles in Europe. In 1801 he created a successful educational institute in which Jews and Christians were educated together and later established the first reformed synagogues, featuring sermons and German, mixed-gender worship, and other innovations. He urged his co-religionists to broaden their religious outlook and place their national loyalties in their immediate countries of origin rather than hoping for the coming of the Messiah and the restoration of the state of Israel. He also succeeded in winning the abolition of special taxes on Jews in several jurisdictions.

Jacobson made substantial progress for his reform program in the short-lived Kingdom of Westphalia (1807–13) during the reign of Napoleon. However, the fall of Napoleon and the opposition of the Orthodox Jewish community resulted in the ultimate failure of his vision during his lifetime. Nevertheless, his ideas succeeded in finding fertile soil in future generations of German and American Jews, among whom he is regarded as one of the leading pioneers of Reform Judaism.

Biography

Early life

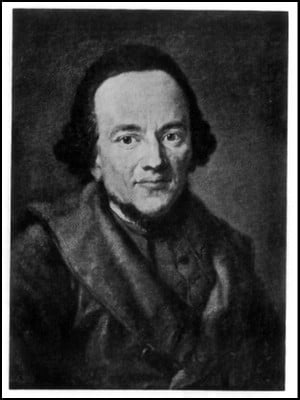

Jacobson was the only son of businessman and philanthropist, Israel Jacob. His parents lived modestly yet contributed considerably to reducing the local Jewish community's debt. Owing to the poor quality of the public schools in his native Halberstadt, Israel attended mainly the Jewish religious school. He seems to have been destined for the rabbinate, but spent his leisure hours studying German literature. He was strongly influenced by the works of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Moses Mendelssohn and joined the Haskalah movement, or Jewish Enlightenment. Not an outstanding student in German, his level of understanding of rabbinic literature and Hebrew, on the other hand, led professors at the University of Helmstedt to declare that Jacobson was a competent Hebrew scholar and grant him his degree.

By the age of 18, his talent for business had enabled him to accumulate a small fortune. He then married Mink Samson, the daughter of respected financier and court agent Hertz Samson. Jacobson's new wife was also the granddaughter of Philip Samson, founder of the Samson-Schule at Wolfenbüttel, at which the noted Jewish intellectuals Leopold Zunz and Isaak Markus Jost were educated.

Through the Samson family, Jacobson became acquainted with Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, who was the favorite nephew of Frederick II of Prussia. Jacobson took up his residence in Brunswick and, possessing great financial ability, rapidly increased his fortune. With the death of his father-in-law in 1795, he succeeded to the latter's position and titles.

Influenced by the writings of Mendelssohn, Jacobson believed that Jewish emancipation could best be effected though a program of secular education for Jewish children which emphasized giving them training in respected professions in German society. He also developed a belief in egalitarian and religious pluralism in education. He believed that it was no longer either useful or religiously required for Jews to adopt an attitude of separation from the Gentile community. He especially believed in the necessity of imbuing the young with the proper religious impressions from an early age.

The Jacobson Institute

In 1801, at his own expense, Jacobson established a school in which 40 Jewish and 20 Christian children were to be educated together. Drawn mainly from families whose parents could not afford to give them a quality education, the children received free board and lodging in Seesen, near the Harz Mountains. This close association of children of different creeds was a favorite idea of his. The Jacobson school soon obtained a wide reputation among Christians as well as Jews. As a result, hundreds of pupils from neighboring towns and villages were educated there. During the 100 years of its existence, the school remained a leading institution in every line of educational endeavor.

In 1804 Jacobson became an official citizen of Brunswick. It was largely due to his influence that the Leibzoll—a special tax which Jews had to pay throughout most of Europe since the Middle Ages—was abolished in Brunswick in 1803. Jacobson also facilitated the abolition of the tax in Baden in 1806. His influence at court continued to rise, and in that same year he was given the title of government finance counselor. In 1807, he was awarded an honorary Ph.D. from the University of Helmstedt, located at the eastern edge of the German state of Lower Saxony.

However, in Brunswick, Jacobson became embroiled in disputes and the intrigues of court officials who resented his influence. As a result, his son Meir's application to join Brunswick's merchants' guild was rejected. Moreover, Jacobson's school, despite its reputation for educational excellence, suffered from lack of support from the authorities.

Napoleon and Westphalia

Jacobson had great hopes that Napoleon would prove to be a friend and emancipator to the Jews. At a gathering of notable Jews in Paris on May 30, 1806, he wrote an enthusiastic letter to Napoleon expressing this hope. In the same year he published a book promoting the idea that a supreme Jewish council be organized by the emperor, headed by a Jewish patriarch and headquartered Paris.

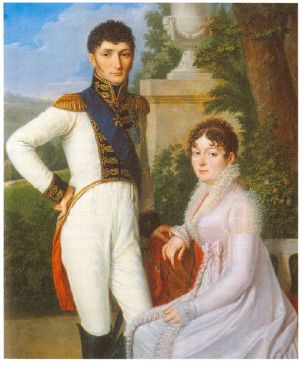

In 1807, when the new Kingdom of Westphalia was organized under the rule of Napolean's brother Jerome, Brunswick came under its jurisdiction. Jacobson lent the kingdom large sums of money, and the resulting debts had the effect of Jacobson's acquiring a great deal of land. The next year, to honor the emancipation of Westphalia's Jews, Jacobson commissioned the creation of a special commemorative medal featuring two angels as the symbol of Judaism and Christianity united in peace.

Jacobson also led in the convening of a new meeting of leading Jews in February 1808 in Cassel with the purpose of introducing religious and other reforms in the Jewish community. Jacobson, who had moved his residence to that of the king at Cassel, was appointed president of the Jewish consistory. In this capacity, assisted by a board of officers, he attempted to exert a reforming influence on the various congregations of the country. His efforts, however, were met with resistance, as the majority of Westphalia's Jews remained Orthodox.

Jacobson nevertheless succeeded in creating the first synagogues which organized themselves according to the reform program. In 1809 a school and and synagogue were opened in Cassel in which prayers were chanted in German as well as in Hebrew. The sermons, too, were given in German. The progressive nature of his religious views was further shown by his strong advocacy of the introduction of the tradition of confirmation, seen by traditionalists as an attack on the institution of bar mitzvah.

In Jacobson's services, references were omitted to a liberating Jewish Messiah who would reintroduce the state of Israel. Rather, Jews were encouraged to act as patriotic citizens of their own nations. Worshipers were not required to cover their heads as in Orthodox synagogues, and daily public worship was replaced with private prayers. Work was allowed on the Sabbath, and the kosher dietary laws were considered optional. Women and men worshiped and studied together. Ethics were stressed, and the idea of the Jews as a specially chosen people was downplayed.

In 1810, Jacobson built a beautiful "temple"—a term which met with objections from the Orthodox community, which reserved the word to refer to the Temple of Jerusalem—within the grounds of his Seesen institute. He demonstrated his reformist attitude dramatically by supplying the synagogue with an organ, the first known instance of this instrument's being placed in a Jewish house of worship. He also encouraged hymns and prayers in German as well as Hebrew. Jacobson himself performed the first five confirmations of Jewish boys at the Seesen temple.

Berlin and later years

After Napoleon's fall (1815), the Kingdom of Westphalia disintegrated, and Jacobson moved to Berlin. There, he continued to work for reforms in Jewish beliefs and liturgy. For this purpose he opened a hall for worship in his own house. The first such service was instituted on the occasion of his son's bar mitzvah in 1815. The services became noted for eloquent sermons delivered by leading reform-minded rabbis and scholars such by "science of Judaism" founder Leopold Zunz, educator Eduard Kley, and others. When the congregation grew to the point that Jacobson's house could no longer accommodate it, the synagogue was relocated to the larger house of banker Jacob Hertz Beer.

However, the Prussian government, remembering Jacobson's French sympathies and receiving continued complaints from the Orthodox rabbis, ordered the services discontinued after about eight months. In 1817, Jacobson succeeded in opening a Reform synagogue in the city, but in 1823 its existence, too, was forbidden, once again as the result of the influence of Orthodox leaders.

During his last years, Jacobson's health deteriorated and the apparent failure of his reform program left him broken in spirit. After two marriages, the majority of his ten children converted to Christianity, dealing a major blow to his vision or Judaism coalescing with mainstream society without being co-opted by it. Although Jacobson continued his philanthropic activities to the end, he is said to have ended his life as an embittered and disappointed man.

Legacy

Throughout his life Jacobson seized every opportunity to promote a better understanding between Jews and Christians, and his great wealth enabled him to support many of the poor of both faiths. In 1852 Jacobson's eldest son, Meir, founded in Seesen an orphan asylum for Jewish and Christian boys.

Even though Jacobson's vision of a reformed Judaism living in harmony with Christianity was not realized in his lifetime, within the succeeding decades, the reform movement had gathered a significant following. It would later become a main stream of Jewish life in Western Europe. Unfortunately, the hope of Jewish-Christian cooperation in Europe was all but destroyed by the rise of Hitler and Nazism.

In the United States, however, Reform Judaism would continue to thrive and is now the largest Jewish denomination. Although Jacobson himself had no direct connection with this trend, the foundations he established in Europe inspired many of the later Jewish reformers. He is recognized today as one of the pioneers of Reform Judaism, even if not its only "father."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Feiner, Shmuel. The Jewish Enlightenment. Jewish culture and contexts. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004. ISBN 9780812237559.

- Gotzmann, Andreas, and Christian Wiese. Modern Judaism and Historical Consciousness: Identities, Encounters, Perspectives. Leiden: Brill, 2007. ISBN 9789004152892.

- Levy, Richard N. A Vision of Holiness: The Future of Reform Judaism. New York: URJ Press, 2005. ISBN 9780807409411.

- Marcus, Jacob Rader. Israel Jacobson: The Founder of the Reform Movement in Judaism. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1972. ISBN 0-87820-000-2.

- Meyer, Michael A. Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 9780195051674.

This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.