Industrialization in the Soviet Union

Industrialization in the Soviet Union occurred as a process of accelerated building-up of the industrial potential of the Soviet Union. The plan was carried out from May 1929 to June 1941, the date of the invasion by Nazi Germany. The goal was to reduce the economy's lag behind the developed capitalist states.

The official task of industrialization was the transformation of the Soviet Union from a predominantly agrarian state into a leading industrial one. The beginning of socialist industrialization as an integral part of the "triple task of a radical reorganization of society" (industrialization, economic centralization, collectivization of agriculture and a cultural revolution) was laid down by the first five-year plan for the development of the national economy lasting from 1928 until 1932.

In Soviet times, industrialization was considered a great feat. The rapid growth of production capacity and the volume of production of heavy industry (four times) was of great importance for ensuring economic independence from capitalist countries and strengthening the country's defense capability. At this time, the Soviet Union made the transition from an agrarian country to an industrial one. During the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet industry proved sufficient in its battle against Nazi Germany, although at great cost in lives and resources. Since the late 1980s, discussions on the price of industrialization have been held in the Soviet Union and Russia, which also questioned its results and long-term consequences for the Soviet economy and society. However, the economies of all post–Soviet states still function with the industrial base that was created in the Soviet period.

GOELRO

During the Civil War, the Soviet government began to develop a long-term plan for the electrification of the country. In December 1920, the GOELRO (State Commission for Electrification of Russia) plan was approved by the 8th All-Russian Congress of Soviets, and a year later it was approved by the 9th All-Russian Congress of Soviets.

The plan provided for the priority development of the electric power industry, tied to the plans for the development of territories. The GOELRO plan, designed for 10–15 years, provided for the construction of 30 district power plants (20 thermal power plants and 10 hydroelectric power plants) with a total capacity of 1.75 gigawatts. The project covered eight major economic regions (Northern, Central Industrial, Southern, Volga, Ural, West Siberian, Caucasian and Turkestan). At the same time, the development of the country's transport system was carried out, including the reconstruction of old as wellas construction of new railway lines and the construction of the Volga–Don Canal.

The GOELRO project made possible the industrialization in the Soviet Union. Electricity generation in 1932 increased almost 7 times compared with 1913, from 2 to 13.5 billion kWh.[1]

Features of industrialization

Researchers highlight the following features of industrialization:

- The main areas selected for investment were the metallurgy, engineering, and industrial construction sectors;

- Pumping funds from agriculture to industry using price scissors;

- The special role of the state in the centralization of funds for industrialization;

- The creation of a single form of ownership—socialist—in two forms: state and cooperative-collective farm;

- Industrialization planning;

- Lack of private capital (cooperative entrepreneurship in that period was legal);

- Relying on own resources (it was impossible to attract private capital in the existing external and internal conditions);

- Over-centralized resources.

The New Economic Policy

Preparations for War

Until 1928, the Soviet economy operated basded on the "New Economic Policy." While agriculture, retail, services, food and light industries were mostly in private hands, the state retained control of heavy industry, transport, banks, wholesale and international trade (the so-called "commanding heights"). State-owned enterprises competed with each other, the role of the government planning commission, or Gosplan, was limited to forecasts that determined the direction and size of public investment.

One of the fundamental contradictions of Bolshevism was that the party that called itself "workers" and its rule the "dictatorship of the proletariat" came to power in an agrarian country where factory workers constituted only a small percentage of the population. Most were recent immigrants from the villages who had not yet completely broken ties with the obshchina, or peasant commune. Forced industrialization was designed to eliminate this contradiction between Marxist theoretical analysis and objective reality.

From a foreign policy point of view, the country found itself in hostile conditions. According to the leadership of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), there was a high probability of a new war with capitalist states. It is significant that even at the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in 1921, Lev Kamenev, the author of the report, "About the Soviet Republic Surrounded," believed that preparations for the Second World War had begun in Europe:[1]

What we see every day in Europe ...testifies that the war is not over, armies move, combat orders are given, garrisons are sent to one or the other area, no borders can be considered firmly established. ...one can expect from hour to hour that the old finished imperialist slaughter will generate, as its natural continuation, some new, even more monstrous, even more disastrous imperialist war.

Preparation for war required a thorough rearmament. The military schools of the Russian Empire, destroyed by the revolution and the Russian Civil War, were rebuilt: military academies, schools, institutes and military courses began training for the Red Army.[2] However, it was impossible to immediately begin technical re-equipment of the Red Army due to the backwardness of heavy industry. The existing rates of industrialization seemed insufficient, as the lag behind the capitalist countries, which had an economic upswing in the 1920s, was increasing.

One of the first such plans for rearmament was laid out as early as 1921, in the draft reorganization of the Red Army prepared for the 10th Party Congress by Sergey Gusev and Mikhail Frunze. The draft stated both the inevitability of a new big war and the unpreparedness of the Red Army for it. Gusev and Frunze suggested organizing mass production of tanks, artillery, armored cars, armored trains, and airplanes in a "shock" order. They also suggested to carefully study the combat experience of the Civil War, including the units that opposed the Red Army, such as officer units of the White Guards, the Makhnovists (Ukrainian anarchists), and General Pyotr Wrangel. The authors also recommended the state urgently organize the publication in Russia of foreign "Marxist" works on military issues.

After the end of the Civil War, Russia again faced the pre-revolutionary problem of agrarian overpopulation (the "Malthusian-Marxist trap"). In the reign of Nicholas II, overpopulation caused a gradual decrease in the average allotments of land. The surplus of workers in the village was not absorbed by the outflow to the cities (amounting to about 300,000 people per year, with an average increase of up to 1 million people per year), nor by emigration in the Stolypin government program of resettling colonists in the Urals. In the 1920s, overpopulation took the form of urban unemployment. It became a serious social problem that grew throughout the period of the New Economic Policy. By the end of NEP this figure was more than 2 million people, or about 10 percent of the urban population.[3] The government believed that one of the factors hindering the development of industry in the cities was the lack of food and the unwillingness of the village to provide the city with bread at low prices, as the peasantry naturally wished to maximize their income.

Debate over Central Planning

The party leadership intended to solve these problems by the planned redistribution of resources between agriculture and industry, in accordance with the concept of socialism, which was announced at the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the 3rd All-Union Congress of Soviets in 1925. In the Stalinist historiography, the 14th congress was called the "industrialization congress," but it made only a general decision about the need to transform the Soviet Union from an agrarian country into an industrial one, without determining the specific forms and rates of industrialization.

The choice of a specific implementation of central planning was vigorously discussed in 1926–1928. Proponents of the genetic approach (Vladimir Bazarov, Vladimir Groman, Nikolai Kondratiev) believed that the plan should be based on objective regularities of economic development, identified as a result of an analysis of existing trends. Proponents of the teleological approach (Gleb Krzhizhanovsky, Valerian Kuybyshev, Stanislav Strumilin) believed that the plan should transform the economy and proceed from future structural changes, production opportunities and rigid discipline. Among the party functionaries, the former were supported by a supporter of the evolutionary path to socialism, Nikolai Bukharin, and the latter by Leon Trotsky, who insisted on an accelerated pace of industrialization.[4]

One of the first ideologues of industrialization was Evgeny Preobrazhensky, an economist close to Trotsky, who in 1924–25 developed the concept of forced "superindustrialization" at the expense of funds from the countryside ("initial socialist accumulation", according to Preobrazhensky). For his part, Bukharin accused Preobrazhensky and the so-called "left opposition" of imposing "feudal military exploitation of the peasantry" and "internal colonialism."

Crisis of 1927 and the end of NEP

Economic policy was intertwined with political struggle as the general secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), Joseph Stalin, initially supported Bukharin's point of view, but after his rival Trotsky's exclusion from the Party's Central Committee in late 1927, he reversed his position, embracing the opposition.[5] This led to a decisive victory for the teleological school and a radical turn from the New Economic Policy. Researcher Vadim Rogovin believes that the cause of Stalin's "left turn" was the grain harvest crisis of 1927; the peasantry, especially the kulaks who were better off. They refused en masse to sell the bread, considering the purchase prices set by the state to be low.

The internal economic crisis of 1927 was intertwined with a deteriorating foreign policy position. On February 23, 1927, the British Foreign Secretary sent a note to the Soviet Union demanding that it stop supporting the Kuomintang–Communist government in China. After the refusal, the United Kingdom on May 24–27 broke off diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union.[6] However, at the same time, the alliance of the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communists fell apart. On April 12, Chiang Kai-shek and his allies massacred the Shanghai Communists. This incident was widely used by the "united opposition" (the "Trotsky-Zinoviev bloc") to criticize the official Stalinist diplomacy as a failure.

In the same period, the Soviet embassy in Beijing (April 6) was raided. British police searched the Soviet-British joint-stock company Arcos in London (May 12). In June 1927, representatives of the Russian All-Military Union conducted a series of terrorist attacks against the Soviet Union. In particular, on June 7, White émigré Koverda killed the Soviet Plenipotentiary in Warsaw, Voykov, on the same day in Minsk, the head of the Belarusian Joint State Political Directorate, Iosif Opansky, was killed. The day before, the Russian All-Military Union terrorist threw a bomb at the Joint State Political Directorate in Moscow. All these incidents contributed to the creation of a paranoia about the emergence of expectations of a new foreign intervention ("crusade against Bolshevism").

By January 1928, only two-thirds of the grain was harvested compared to the previous year's level, as the peasants withheld bread, considering the purchase price offered by the government to be too low. The disruptions in the supply of cities and the army that had begun were aggravated by the exacerbation of the foreign policy situation, which reached the point of a trial mobilization. In August 1927, a panic began among the population, which resulted in the stockpiling of extra food in the expectation of future catastrophe. At the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (December 1927), Mikoyan admitted that the country had experienced the difficulties of "the eve of war without having a war."

First five-year plan

In 1928, the first five-year plan was introduced to replace the NEP. The main task of the newly introduced command economy was to build up the economic and military power of the state at the highest possible rates, accompanied with the near complete elimination of private industry that had been permitted under NEP. In the initial stage, it amounted to the redistribution of the maximum possible amount of resources for the needs of state-owned industrialization. In December 1927, at the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), "Directives for drafting the first five-year national economic development plan of the Soviet Union" were adopted. The Congress spoke out against super-industrialization: growth rates should not be maximal and should be planned so that failures do not occur.[7] Developed on the basis of directives, the draft of the first five-year plan (October 1, 1928 – October 1, 1933) was approved at the 16th Conference of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (April 1929). This plan was much more stressful than previous projects. Immediately after it was approved by the 5th Congress of Soviets in May 1929, it provided that grounds for the state to carry out a number of economic, political, organizational and ideological measures to promote industrialization. The era of the "Great Turn" was initiated. The country had to expand the construction of new industries, increase the production of all types of products and start producing new equipment.

We are 50–100 years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in ten years. Either we do it, or they crush us.[8]

Mobilization

Using propaganda, the party leadership mobilized the population in support of industrialization.[9] Komsomol members, in particular, took to it with enthusiasm. There was no shortage of cheap labor, because after collectivization, a large number of rural inhabitants moved from rural areas to cities to escape poverty, hunger and the arbitrariness of the authorities.[10] Millions of people,[11] almost by hand, built hundreds of factories, power stations, laid railways, and subways, often working three shifts round the clock. In 1930, around 1,500 facilities were launched, of which 50 absorbed almost half of all investments. With the assistance of foreign specialists, a number of giant industrial buildings were erected: DneproGES, metallurgical plants in Magnitogorsk, Lipetsk and Chelyabinsk, Novokuznetsk, Norilsk and Uralmash, tractor plants in Stalingrad, Chelyabinsk, Kharkov, Uralvagonzavod, GAZ, ZIS (modern ZiL) among others. In 1935, the first line of the Moscow Metro opened with a total length of {{safesubst:#invoke:convert|convert|abbr=on always|warnings=1}}.

Attention was paid to the destruction of private agriculture and its replacement by state-run large kolhozy (collective farms). Due to the emergence of domestic tractor construction, in 1932, the Soviet Union refused to import tractors from abroad, and in 1934, the Kirov Plant in Leningrad began to produce a tilled tractor, "Universal," which became the first domestic tractor exported abroad. In the ten years before [[World War II], about 700,000 tractors were produced, which accounted for 40 percent of world production.[12]

In order to create its own engineering base, the domestic system of higher technical education was urgently created.[13] In 1930, universal primary education was introduced in the Soviet Union, with seven-year compulsory education in the cities.

Creating Socialism in One Country

In 1930, speaking at the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), Stalin argued that an industrial breakthrough was possible only when building "socialism in one country," demanding the five-year plan be exceeded.[14] (Stalin's theory was counterposed to Trotsky's Permanent revolution).

In order to increase incentives to work, payment has become more tightly attached to performance. Actively developed centers for the development and implementation of the principles of the scientific organization of labor emerged. One of the largest centers of this kind, the Central Institute of Labor, created about 1,700 training points with 2,000 of the most qualified instructors of the Central Labor Institute in different parts of the country. They operated in all leading sectors of the national economy—in engineering, metallurgy, construction, light and timber industries, on railways and motor vehicles, in agriculture and even in the navy.[15]

In 1933, at the joint plenum of the Central Committee and the Central Control Commission of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), Stalin said in his report that according to the results of the first five-year plan, consumer goods produced were less than needed, but the policy of moving industrialization to the background would mean that the country would not have a tractor and automobile industry, ferrous metallurgy, or metal for the production of machines. The country would have to do without bread. He argued that capitalist elements in the country would incredibly increase the chances for the restoration of capitalism. Their position would become similar to that of China, which at that time did not have its own heavy and military industry, and became the object of aggression. Instead of non-aggression pacts with other countries, there would be military intervention and war - a dangerous and deadly war, a bloody and unequal war, for in this war the Soviets would be almost unarmed before the enemies, having at its disposal all modern means of attack.[16]

In 1935, the "Stakhanovist movement" appeared, in honor of the mine worker Alexey Stakhanov, who, according to official information of that time, performed 14.5 norms for a shift on the night of August 30, 1935. Stakhanov became the face of the Soviet industrialization push.

Concentration of Power in the State

The state shifted to the centralized distribution of the means of production and consumer goods, introducing command-administrative methods of management and the nationalization of private property. A political system emerged based on the leading role of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), state ownership of the means of production and a minimum of private initiative. This led to a number of problems.

The first five-year plan was associated with rapid urbanization. The urban labor force increased by 12.5 million people, of whom 8.5 million were migrants from rural areas. However, the Soviet Union would reach a 50 percent share of urban population only in the early 1960s. Since capital investments in heavy industry almost immediately exceeded the previously planned amount and continued to grow, money emission was sharply increased (that is, printing of paper money), and during the entire first five-year period money supply growth in circulation more than doubled the production of consumer goods, which led to higher prices and a shortage of consumer goods.

After the nationalization of foreign concessions for gold mining against the Soviet Union, a "golden boycott" was declared. In response paintings from the Hermitage collection were sold to obtain the foreign currency needed to finance industrialization. More ominously, they began the widespread use of forced labor by prisoners of the Gulag, special settlers and rear militia.

Use of foreign specialists

Engineers were invited from abroad. Many well-known companies, such as Siemens-Schuckertwerke AG and General Electric, were involved in the work and carried out deliveries of modern equipment. A significant part of the equipment models produced in those years at Soviet factories were copies or modifications of foreign analogues (for example, a Fordson tractor assembled at the Stalingrad Tractor Plant).

In February 1930, between Amtorg and Albert Kahn, Inc., a firm of American architect Albert Kahn, an agreement was signed according to which Kahn's firm became the chief consultant of the Soviet government on industrial construction. They received a package of orders for the construction of industrial enterprises worth $2 billion (more than $250 billion in today's prices). This company provided construction of more than 500 industrial facilities in the Soviet Union.[17]

A branch of Albert Kahn, Inc. was opened in Moscow under the name "Gosproektstroy" (State Design and Construction Bureau). Its leader was Moritz Kahn, brother of the head of the company. It employed 25 leading American engineers and about 2,500 Soviet employees. At that time it was the largest architectural bureau in the world. During the three years of the existence of Gosproektroy, more than 4,000 Soviet architects, engineers and technicians studied the American experience. The Moscow Office of Heavy Machinery, a branch of the German company Demag, also worked in Moscow.

The firm of Albert Kahn played the role of coordinator between the Soviet customer and hundreds of Western companies that supplied equipment and advised the construction of individual projects. Thus, the technological project of the Nizhny Novgorod Automobile Plant was completed by Ford, the construction project by the American company Austin Motor Company. Construction of the 1st State Bearing Plant in Moscow, which was designed by Kahn, was carried out with the technical assistance of the Italian company, RIV.

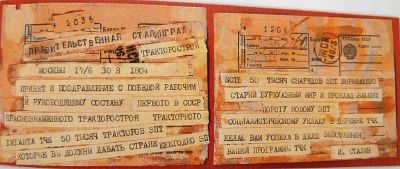

The Stalingrad Tractor Plant, designed by Kahn in 1930, was originally built in the United States, and then was unmounted, transported to the Soviet Union and assembled under the supervision of American engineers. It was equipped by more than 80 American engineering companies and several German firms.

American hydrobuilder Hugh Cooper became the chief consultant for the construction of the DneproGES, hydro turbines which were purchased from General Electric and Newport News Shipbuilding.[18]

The Magnitogorsk Metallurgical Plant was designed by the American firm Arthur G. McKee and Co., which also supervised its construction. A standard blast furnace for this and all other steel mills of the industrialization period was developed by the Chicago-based Freyn Engineering Co.[19]

Legacy

| Products | 1928 | 1932 | 1937 | 1928 to 1932 (%) 1st Five-Year Plan |

1928 to 1937 (%) 1st and 2nd Five-Year Plans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cast iron, million tons | 3.3 | 6.2 | 14.5 | 188 | 439 |

| Steel, million tons | 4.3 | 5.9 | 17.7 | 137 | 412 |

| Rolled ferrous metals, million tons | 3.4 | 4.4 | 13 | 129 | 382 |

| Coal, million tons | 35.5 | 64.4 | 128 | 181 | 361 |

| Oil, million tons | 11.6 | 21.4 | 28.5 | 184 | 246 |

| Electricity, billion kWh | 5.0 | 13.5 | 36.2 | 270 | 724 |

| Paper, thousand tons | 284 | 471 | 832 | 166 | 293 |

| Cement, million tons | 1.8 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 194 | 306 |

| Sugar, thousand tons | 1,283 | 1,828 | 2,421 | 142 | 189 |

| Metal-cutting machines, thousand pieces | 2.0 | 19.7 | 48.5 | 985 | 2,425 |

| Cars, thousand pieces | 0.8 | 23.9 | 200 | 2,988 | 25,000 |

| Leather shoes, million pairs | 58.0 | 86.9 | 183 | 150 | 316 |

At the end of 1932, the successful and early implementation of the first five-year plan in four years and three months was announced. Summarizing its results, Stalin announced that heavy industry had fulfilled the plan by 108 percent. During the period between October 1, 1928 and January 1, 1933, the production of fixed assets of heavy industry increased 2.7 times.

In report at the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in January 1934, Stalin cited the following figures with the words: "This means that our country has become firmly and finally an industrial country."[21]

| 1913 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry (without small) | 42.1 | 54.5 | 61.6 | 66.7 | 70.7 | 70.4 |

| Agriculture | 57.9 | 45.5 | 38.4 | 33.3 | 29.3 | 29.6 |

The second five-year plan followed the first with a somewhat lesser emphasis on industrialization, and then the third five-year plan, which was thwarted by the outbreak of World War II.

The result of the first five-year plans was the development of heavy industry. The increase in gross domestic product during 1928–40, according to Vitaly Melyantsev, was about 4.6% per year (according to other, earlier estimates, from 3% to 6.3%).[22] Industrial production in the period 1928–1937 increased 2.5–3.5 times, that is, 10.5–16% per year.[23] In particular, the release of machinery in the period 1928–1937 grew on average 27.4% per year.[24] From 1930 to 1940, the number of higher and secondary technical educational institutions in the Soviet Union increased 4 times, exceeding 150.[13]

By 1941, about 9,000 new plants were built.[25] By the end of the second five-year plan, the Soviet Union took the second place in the world in industrial output, second only to the United States.[25] Imports fell sharply, which was viewed as the country's gaining economic independence. Open unemployment had been eliminated. Employment (at full rates) increased from one third of the population in 1928 to 45 percent in 1940, which provided about half of the growth of the gross national product.[26] For the period 1928–1937 universities and colleges prepared about two million specialists. Many new technologies were mastered. During the first five-year period the production of synthetic rubber, motorcycles, watches, cameras, excavators, high-quality cement and high-quality steel grades increased.[23] The foundation was also laid for Soviet science, which in certain areas eventually became world-leading. On the basis of the established industrial base, it became possible to conduct a large-scale re-equipment of the army. During the first five-year plan, defense spending rose to 10.8 percent of the budget.[27]

However, with the onset of industrialization, the consumption fund, and as a result, the standard of living of the population, sharply decreased.[28] The Collectivization of Soviet agriculture proved vexing. By the end of 1929, the rationing system was extended to almost all food products, but the shortage of rations remained. There were long queues to buy foodstuffs. Only later did the standard of living begin to improve. In 1936, the ration cards were canceled, which was accompanied by an increase in wages in the industrial sector and an even greater increase in state rations prices for all goods. The average level of per capita consumption in 1938 was 22% higher than in 1928.[28] However, the greatest growth was among the party and labor elite and did not at all touch the overwhelming majority of the rural population, or more than half of the country's population.[28]

| Products | 1913 | 1940 | 1940 to 1913 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity production, billion kWh | 2.0 | 48.3 | 2,400 |

| Steel, million tons | 4.2 | 18.3 | 435 |

End of the Industrialization Era

The end date of the period of industrialization is calculated by different historians in different ways. From the point of view of the conceptual aspiration to raise heavy industry in record time, the first five-year plan was the most successful period. Most often, the end of industrialization is understood as the last pre-war year (1940), less often the year before Stalin's death (1952). If industrialization is understood as a process whose goal is the share of industry in the gross domestic product, characteristic of industrialized countries, then the economy of the Soviet Union reached such a state only in the 1960s. If we take into account the social aspect of industrialization, it was only in the early 1960s that urban population exceeded rural.

Soviet economist and secretary of the party committee at Leningrad University, Nikolai Kolesov Dmitrievich, believes that without the implementation of the industrialization policy, the political and economic independence of the country would not have been ensured.[29] Sources of funds for industrialization and its pace were predetermined by economic backwardness and too short a period allowed for its liquidation. According to Kolesov, the Soviet Union managed to eliminate the backwardness in just 13 years.

Criticism

During the years of Soviet power, the Communists argued that the basis of industrialization was a rational and achievable plan.[30] The plan was for the first five-year plan to take effect at the end of 1928, but even by the time of its announcement in April–May 1929, the work on its compilation was not completed. The initial form of the plan included goals for 50 industries and agriculture, as well as the relationship between resources and opportunities. Over time, the achievement of predetermined indicators began to play a major role. If the growth rates of industrial production originally set at 18–20%, by the end of the year they were doubled. Western and Russian researchers argue that despite the report on the successful implementation of the first five-year plan, the statistics were falsified,[25][30] and none of the goals were even remotely achieved.[25]For example, the plan for the production of pig iron was fulfilled by only 62%, steel by 56%, rolled products by 55%, and coal by 86%. Moreover, in agriculture and in industries dependent on agriculture, there was a sharp decline.[23][25] Part of the party nomenklatura was extremely outraged by this. Sergey Syrtsov described the reports on the achievements as "fraud."[30]

According to Boris Brutskus, it was poorly thought out, which manifested itself in a series of announced "fractures" (April–May 1929, January–February 1930, June 1931). A grandiose and thoroughly politicized system emerged, the characteristic features of which were economic "gigantomania," chronic commodity hunger, organizational problems, wastefulness, and loss-making enterprises.[31] The goal (that is, the plan) began to determine the means for its implementation. According to the findings of prominent Soviet historians in the West, (Robert Conquest, Richard Pipes, etc.), the neglect of material support and the development of infrastructure over time began to cause significant economic damage.[30] Some of the industrialization endeavors are considered by critics to have been poorly thought out from the start. Jacques Rossi argues that the White Sea–Baltic Canal was unnecessary.[32] According to Soviet statistics, already in 1933, 1.143 million tons of cargo and 27,000 passengers were transported along the canal;[33] in 1940, about one million tons,[34] and in 1985, 7.3 million tons of cargo.[35] However, the incredibly brutal conditions in the building of the canal resulted in the death of up to 25,000 able-bodied working-age Soviet citizens.[36] This not only deprived the Soviet Union of their labor but reduced the pool of manpower for military service to counter Nazi German aggression only eight years later.

Despite the development of output, industrialization was carried out mainly by extensive methods: economic growth was ensured by an increase in the gross capital formation rate in fixed capital, a savings rate (due to a fall in the consumption rate), employment rates and the exploitation of natural resources.[37] British scientist Don Filzer believes that this was due to the fact that as a result of collectivization and a sharp decline in the standard of living of the rural population, human labor was greatly devalued.[38] Vadim Rogovin notes that the desire to fulfill the plan led to a situation of overstretching forces and a permanent search for reasons to justify the non-fulfillment of excessive tasks.[39] Because of this, industrialization could not feed solely on enthusiasm and demanded a series of compulsory measures.[30][39] From October 1930, the free movement of labor was prohibited and criminal penalties were imposed for violations of labor discipline and negligence. From 1931, workers were held responsible for damage to equipment.[30] In 1932 the forced transfer of labor between enterprises became possible and the death penalty was introduced for the theft of state property. On December 27, 1932, an internal passport was restored, which Lenin had previously condemned as "czarist backwardness and despotism." The seven-day week was replaced by a full working week, the days of which, without names, were numbered from 1 to 5. On every sixth day, there was a day off for work shifts, so that factories could work without interruption. Prisoners' labor was actively used (see Gulag). In fact, during the first five-year plan the communists laid the foundations for forced labor for the Soviet population.[40] All this became the subject of sharp criticism in democratic countries, and not only by liberals, but also by social democrats.[41]

Workers' discontent from time to time turned into strikes, including strikes at the Stalin plant, the Voroshilov plant, the Shosten plant in Ukraine, the Krasnoye Sormovo plant near Nizhny Novgorod, the Serp and Molot plant of Mashinootrest in Moscow, the Chelyabinsk Traktorstroy as well as other enterprises.

Impact on peasantry

Industrialization also entailed the collectivization of agriculture. Agriculture had become a source of government revenue, due to low purchase prices for grain internally and subsequent export at higher prices, as well as due to the so-called "super tax in the form of overpayments for manufactured goods."[42] In the future, the peasantry also ensured the growth of heavy industry by labor. The short-term result of this collectivization policy was a temporary drop in agricultural production. The consequence of this was the deterioration of the economic situation of the peasantry,[23] resulting in famine in the Soviet Union of 1932–33. Compensation for the losses of the village required additional costs. In 1932–1936, the collective farms received about 500,000 tractors from the state, not only for mechanizing the cultivation of the land, but also to compensate for the damage from the reduction in the number of horses by 51 percent (77 million) in 1929–1933. The mechanization of labor in agriculture and the unification of separate land plots ensured a significant increase in labor productivity.

Questions over productivity

Trotsky and foreign critics argued that, despite efforts to increase labor productivity, in practice, average labor productivity fell.[43] This is stated in a number of modern publications,[26] according to which for the period 1929–1932 value added per hour of work in industry fell by 60 percent and returned to the level of 1929 only in 1952. This is explained by the emergence in the economy of chronic commodity shortages, collectivization, mass hunger, a massive influx of untrained workforce from the countryside and an increase in their labor resources by enterprises. At the same time, the specific gross national product per worker in the first 10 years of industrialization grew by 30 percent.[26]

As for the records of the Stakhanovists, a number of historians note that their methods were a continuous method of increasing productivity,[44] previously popularized by Frederick Taylor and Henry Ford, which Lenin called the "sweatshop system." In addition, records were largely staged and were the result of the efforts of their assistants,[45][46] and in practice turned the pursuit of quantity at the expense of product quality. Due to the fact that wages were proportional to productivity, the wages of Stakhanovists were several times higher than the average wages in industry. This caused a hostile attitude towards the Stakhanovists from the "backward" workers, who reproached them with the fact that their records lead to higher standards and lower prices.[47] Newspapers talked about the "unprecedented and blatant sabotage" of the Stakhanov movement by masters, shop managers, trade union organizations.

Political repression

The exclusion of Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev from the party at the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) gave rise to a wave of repressions in the party[48] that spread to the technical intelligentsia and foreign technical specialists. At the July plenum of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of 1928, Stalin advanced the thesis that "as we move forward, the resistance of the capitalist elements will increase, the class struggle will escalate." In the same year, the campaign against sabotage began. The "pests" were blamed for failing to achieve the targets of the plan. The first high-profile trial of the "pest" case was the Shakhty Trial, after which charges of sabotage could follow the company's failure to comply with the plan.[49]

One of the main goals of forced industrialization was to overcome the lag behind developed capitalist countries. Some critics argue that this lag was in itself primarily a consequence of the October Revolution.[40] They draw attention to the fact that in 1913 Russia ranked fifth in world industrial production[50] and was the world leader in industrial growth with an indicator of 6.1 percent per year for the period 1888–1913.[51] However, by 1920, the level of production fell ninefold compared with 1916.[52]

Soviet propaganda claimed that economic growth was unprecedented.[53] On the other hand, in a number of modern studies, it is proved that the growth rate of gross domestic product in the Soviet Union (the above-mentioned[22] 3–6.3%) were comparable with the similar figures in Germany in 1930–38 (4.4%) and Japan (6.3%), although they were significantly superior to those of countries such as United Kingdom, France and the United States that were experiencing the Great Depression at that time.[54]

For the Soviet Union of that period, authoritarianism and central planning in the economy were characteristic. At first glance, this gives weight to the popular belief that the high rates of increasing industrial output of the Soviet Union were obliged to the authoritarian regime and planned economy. However, a number of economists believe that the growth of the Soviet economy was achieved only due to its extensive nature.[37] As part of counterfactual historical studies, or so-called "virtual scenarios," it was suggested that, if the New Economic Policy were preserved, industrialization and rapid economic growth would have also been possible.[55]

Industrialization and the Great Patriotic War

One of the main goals of industrialization was building up the military potential of the Soviet Union. As of January 1, 1932, there were 1,446 tanks and 213 armored vehicles in the Red Army. By January 1, 1934 they had 7574 tanks and 326 armored vehicles—more than in the armies of United Kingdom, France and Nazi Germany combined.[40]

The relationship between industrialization and the victory of the Soviet Union over Nazi Germany in the "Great Patriotic War" is a matter of debate. In Soviet times, the view was adopted that industrialization and pre-war rearmament played a decisive role in the victory. However, the superiority of Soviet technology over the German one on the western border of the country on the eve of the war[56] could not stop the enemy.

According to the historian Konstantin Nikitenko,[57] the command-administrative system that was built up nullified the economic contribution of industrialization to the country's defense capability. Vitaly Lelchuk argues that by the beginning of the winter of 1941 the occupied territory was where 42 percent of the population of the Soviet Union lived, 63 percent of coal were mined, 68 percent of pig iron smelted before the war.[25] Lelchuk notes that "Victory had to be forged not with the help of the powerful potential that was created during the years of accelerated industrialization." The material and technical base of such giants built during the years of industrialization, such as Novokramatorsk and Makeevka metallurgical plants, DneproGES, among others, was at the disposal of the invaders.

But supporters of the Soviet point of view object that industrialization most affected the Urals and Siberia, while pre-revolutionary industry turned out to be in the occupied territories. They also indicate that the prepared evacuation of industrial equipment to the regions of the Urals, the Volga region, Siberia and Central Asia played a significant role. In the first three months of the war alone, 1,360 large (mostly military) enterprises were displaced.[58]

Industrialization in literature and art

Poetry

- Vladimir Mayakovsky. The Story of Khrenov About Kuznetskstroi and About the People of Kuznetsk (1929)

Prose

- Andrey Platonov. The Foundation Pit (1930)

- Alexander Malyshkin. Outback people (1938)

Sculpture

- Vera Mukhina. Worker and Kolkhoz Woman (Moscow, 1937)

- Alexey Zelensky and Vasily Bohun. Metallurgist (Magnitogorsk, 1958)

Film

- Ivan. Director Alexander Dovzhenko (1932)

- Bright Path. Director Grigory Alexandrov (1940)

- Time, Forward!. Director Mikhail Schweitzer (1965)

- Man of Marble. Director Andrzej Wajda (1977) – the film is dedicated to Poland in the 1950s, but there is a parallel with the Soviet movement of the Stakhanovists.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pavel Kravchenko, Orthodox World (National Idea of the Centuries-Old Development of Russia) (Moscow, RU: Издательство Aegitas, 2017, ISBN 978-1773132150), 441-442. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ↑ David Petrovsky, Military School During the Revolution (1917–1924) (Moscow, RU: The Supreme Military Editorial Board, 1924).

- ↑ Vladimir Kamynin, "Soviet Russia at the Beginning and the Middle of the 1920s," in Soviet Russia in the early and mid-20s, Course of Lectures, ed. Boris Lichman (Yekaterinburg: Ural State Technical University, 1995), 159. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ Vadim Rogovin, "On 'super-industrialization', 'robbery of the peasantry' and popular measures." in World Revolution and World War (1998, ISBN 5852720283). Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ Alexander Nove, "About the fate of the NEP," Questions of History (№8) (1989): 172. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Military alarm" in the USSR in 1927: Anglo-Soviet Conflict 1927," Chronos Library. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ Lyudmila Rogachevskaya, "How Was the Plan of the First Five-Year Plan," Vostok (East) 3(27) (March 2005). Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ Joseph Stalin, "On the Tasks of Business Executives: Speech at the First All-Union Conference of Socialist Industry Workers," Chronos Library, February 4, 1931. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ↑ Peter Kenez, The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917—1929 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0511572623).

- ↑ Hays Kessler "Collectivization and the Flight From Villages – Socio-Economic Indicators, 1929–1939," ed. Leonid Borodkin, Economic History (October 23, 2002): 77. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ Vadim Rogovin, Was There an Alternative? (Moscow, RU: Iskra-Research, 1993). Retrieved March 20, 2023. "The enthusiasm and dedication of millions of people during the first five-year plan is not an invention of Stalinist propaganda, but the undoubted reality of that time."

- ↑ Vyacheslav Rodichev and Galina Rodicheva, Tractors and Automobiles 2nd ed. (Moscow, RU: Agropromizdat, 1987, ISBN 978-5030008554). Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 David Alexandrovich Petrovsky, Reconstruction of the Technical School and the Five-Year Frame (Leningrad, RU: Gostekhizdat, 1930), 5.

- ↑ Ilya Ratkovsky and Mikhail Khodyakov, History of Soviet Russia (Saint Petersburg, RU: St. Petersburg State University, 2001), Chapter 3. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Taylor and Gastev," Expert Magazine (№18) (703) (May 10, 2010). Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ Joseph Stalin, "Results of the first five-year plan: Report at the joint plenum of the Central Committee and the Central Control Commission of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) on January 7, 1933," Writings, Volume 13 (Moscow, RU: State Publishing House of Political Literature, 1951), 161–215. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ↑ Mark Meerovich, "Albert Kahn in the History of Soviet Industrialization," www.archi.ru., May 27, 2009. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ Katherine Siegel, Loans and Legitimacy: The Evolution of Soviet–American Relations, 1919–1933 (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2014, ISBN 978-0813160351), 86.

- ↑ Walter Dunn, The Soviet Economy and the Red Army, 1930–1945 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1995, ISBN 978-0275948931), 12.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Soviet Union in Numbers in 1967 Moscow, RU: 1968.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Joseph Stalin, "Report to the 17th Party Congress on the work of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), January 26, 1934," Joseph Stalin, Writings, Volume 13 (Moscow, RU: State Publishing House of Political Literature, 1951), 282. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Vitaly Melyantsev, "Russia for Three Centuries: Economic Growth in the Global Context," Social Sciences and Modernity (№ 5) (2003): 84–95. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Stephen G. Wheatcroft, R.W. Davies, and J.M. Cooper, "Soviet Industrialization Reconsidered: Some Preliminary Conclusions about Economic Development between 1926 and 1941," Economic History Review, 2nd ser. 39(2) (1986): 264.

- ↑ R. Moorsteen, Prices and Production of Machinery in the Soviet Union, 1928—1958 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Vitaly Lelchuk, And Industrialization. Russian Library. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 M. Harrison, "Trends in Soviet Labor Productivity, 1928—1985: War, Postwar Recovery, and Slowdown," European Review of Economic History 2(2) (1998): 171. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ M. Harrison and R.W. Davis, "The Soviet Military-Economic Effort during the Second Five-Year Plan (1933—1937)," Europe-Asia Studies 49(3) (1997): 369.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 R.C. Allen, "The standard of living in the Soviet Union, 1928—1940," University of British Columbia, Dept. of Economics. Discussion Paper 97(18) (August 1997). Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ Nikolay Kolesov, "The Economic Factor of Victory in the Battle of Stalingrad," Problems of the Modern Economy (№3) (2002). Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 J.C. Dewdney, Richard Pipes, Robert Conquest, and M. McCauley, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics" (Chicago, IL: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2007, ISBN 1593392362), 671. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ↑ Boris Brutskus, "'Five-Year Plan' and its Execution," Contemporary Notes (44) (1930).

- ↑ Jacques Rossi, Guide to the Gulag (Moscow, RU: Prosvet, 1991). Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ V.I. Volkov, "Meet the Anniversary: The White Sea-Baltic Canal and Communication Systems – 70 years," (in Russian) Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ↑ Paul R. Gregory, The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag, ed. Valery Lazarev (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0817939427), Chapter 8: "The White Sea-Baltic Canal." Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ↑ "The most important events in the history of the White Sea - Baltic Canal," Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ Anne Applebaum Gulag: A History (London, U.K.: Penguin, 2003, ISBN 0767900561), 79.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 S. Fischer, "Russia and the Soviet Union Then and Now," NBER Working papers (4077) (1992). Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ D. Filtzer, Soviet Workers and Stalinist Industrialization: The Formation Of Modern Soviet Production Relations, 1928-1941 (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe Press, 1986).

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Vadim Rogovin,"Methods of Stalinist Industrialization," Was There an Alternative (Moscow, RU: Iskra-Research, 1993), Chapter 24. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Kirill Alexandrov, "Industrialisation vs. the Great Depression," Gazeta.ru, May 15, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ Ian Adams, Political Ideology Today, 2nd. ed. (Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0719060199), 136.

- ↑ Paul Roderick Gregory, Political Economy of Stalinism (Moscow, RU: ROSSPEN, 2008).

- ↑ Leon Trotsky, A Revolution Betrayed: What is the USSR and Where Is it Going, Chapter 2. ed. Felix Kreisel. Iskra Research, 1999. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ D.A. Wren and A.G. Bedeian, "The Taylorization of Lenin: rhetoric or reality?" International Journal of Social Economics 31(3) (2004): 287.

- ↑ Katerina Clark, "Positive Hero as a Verbal Icon," Socialist Realistic Canon, Saint Petersburg: "Academic Project," 2000.

- ↑ Valentina Voloshina and Anastasia Bykova, Soviet Period of Russian History (1917–1993) (Omsk, RU: Publishing House of Omsk State University, 2001), Chapter 8: Industrialization.

- ↑ Vadim Rogovin, Stalin's Neo-NEP, Chapter 36: Stakhanov Movement. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ Vadim Rogovin, Power and Opposition Chapter 3: The First Round of Reprisals against the Left Opposition. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ Alexander Igolkin, Oil workers–"pests" Oil of Russia (№ 3) (2005). Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ Paul Roderick Gregory, Russian National Income: 1885—1913 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0521243827).

- ↑ Manabu Suhara, Russian Industrial Growth: An Estimation of a Production Index, 1860—1913 College of Economics, Nihon University 5(3) (2005). Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ R.W. Davies, The economic transformation of the Soviet Union, 1913—1945 ed. R. W. Davies, M. Harrison, and S. G. Wheatcroft (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-1139170680), Chapter 7: Industry.

- ↑ Joseph Stalin, "The Bolshevik Party in the Fight for the Completion of the Building of the Socialist Society and the Implementation of the New Constitution: (1935-1937)," A Short Course of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). Chapter 12, Section 2. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ↑ Angus Maddison, Phases of Capitalist Development (Oxford, U.K. and New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0198284505).

- ↑ Robert C. Allen, Capital accumulation, soft budget constraints and Soviet industrialization, trans. Dmitry Nitkinm (Vancouver, B.C.: University of British Columbia, 1997). Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ↑ Mikhail Meltyukhov, Lost chance of Stalin: The Soviet Union and the struggle for Europe: 1939–1941 (Moscow, RU: Veche, 2000), Chapter 12. The Place of the "Eastern Campaign" in the Strategy of Germany 1940–1941 and the Forces of the Parties to the Beginning of Operation Barbarossa. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ↑ Konstantin Nikitenko, "The Catastrophe of 1941: How Was it Possible? Command-Administrative Control System in Stalinist way: the Mountain Gave Birth to a Mouse," The Mirror of the Week (№ 23) (803) (June 19, 2010). Retrieved March 22, 2023. (in Russian)

- ↑ "Moving the Productive Forces of the Soviet Union to the East,". Retrieved March 22, 2023. (in Russian)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, Ian. Political Ideology Today, 2nd. ed. Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0719060199

- Applebaum, Anne. Gulag: A History. London, U.K.: Penguin, 2003. ISBN 0767900561

- Davies, R.W. The economic transformation of the Soviet Union, 1913—1945, ed. R. W. Davies, M. Harrison, S. G. Wheatcroft. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-1139170680

- Dunn, Walter, The Soviet Economy and the Red Army, 1930–1945. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1995, ISBN 978-0275948931

- Filtzer, D. Soviet Workers and Stalinist Industrialization: The Formation Of Modern Soviet Production Relations, 1928-1941. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe Press, 1986.

- Gregory, Paul Roderick, Russian National Income: 1885—1913. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0521243827

- Gregory, Paul R. The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag, ed. Valery Lazarev. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0817939427

- Gregory, Paul Roderick. Political Economy of Stalinism. Moscow, RU: ROSSPEN, 2008.

- Kenez, Peter. The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917—1929. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0511572623

- Kravchenko, Pavel. Orthodox World (National Idea of the Centuries-Old Development of Russia)]. Moscow, RU: Издательство Aegitas, 2017. ISBN 978-1773132150

- Lichman, Boris (ed.). Soviet Russia in the early and mid-20s, Course of Lectures. Yekaterinburg: Ural State Technical University, 1995.

- Maddison, Angus. Phases of Capitalist Development. Oxford, U.K. and New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0198284505

- Moorsteen, R. Prices and Production of Machinery in the Soviet Union, 1928—1958. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962.

- Petrovsky, David Alexandrovich. Military School During the Revolution (1917–1924). Moscow, RU: The Supreme Military Editorial Board, 1924.

- Petrovsky, David Alexandrovich. Reconstruction of the Technical School and the Five-Year Frame. Leningrad, RU: Gostekhizdat (State Publishing House), 1930.

- Ratkovsky, Ilya, and Mikhail Khodyakov. History of Soviet Russia. Saint Petersburg, RU: St. Petersburg State University, 2001.

- Rodichev, Vyacheslav, and Galina Rodicheva. Tractors and Automobiles 2nd ed. Moscow, RU: Agropromizdat, 1987. ISBN 978-5030008554

- Rogovin, Vadim. World Revolution and World War. 1998. ISBN 5852720283

- Siegel, Katherine. Loans and Legitimacy: The Evolution of Soviet–American Relations, 1919–1933. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2014. ISBN 978-0813160351

- Voloshina, Valentina, and Anastasia Bykova. Soviet Period of Russian History (1917–1993). Omsk, RU: Publishing House of Omsk State University, 2001.

External links

All links retrieved March 29, 2023.

- "Taylor and Gastev," Expert Magazine (№18) (703) (May 10, 2010).

- "Military alarm" in the USSR in 1927: Anglo-Soviet Conflict 1927," Chronos Library.

- Gartman, David, and M. Ilchenko, Post-Fordism_Conceptions_Institutions_Practices ed by M. Ilchenko and V. Martyanov. Moscow, RU: ROSSPEN_Publishing, 2015, ISBN 978-5824319958.

- Melnikova-Raich, Sonia. "The Soviet Problem with Two 'Unknowns': How an American Architect and a Soviet Negotiator Jump-Started the Industrialization of Russia. Part I: Albert Kahn" IA, Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 36(2) (2010).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.