Hindu leadership

| Part of the series on Hinduism | |

| |

| History · Deities | |

| Denominations · Mythology | |

| Beliefs & practices | |

|---|---|

| Reincarnation · Moksha | |

| Karma · Puja · Maya | |

| Nirvana · Dharma | |

| Yoga · Ayurveda | |

| Yuga · Vegetarianism | |

| Bhakti · Artha | |

| Scriptures | |

| Upanishads · Vedas | |

| Brahmana · Bhagavad Gita | |

| Ramayana · Mahabharata | |

| Purana · Aranyaka | |

| Related topics | |

| Hinduism by country | |

| Leaders · Mandir · | |

| Caste system · Mantra | |

| Glossary · Hindu festivals | |

| Murti | |

Hinduism is an umbrella term for various religious traditions that originated in India, and now are practiced all around the world, though more than 90% of Hindus are found in India. The third largest organized religion in the world, after Christianity and Islam, Hinduism is based on the teachings of the Vedas, ancient scriptures, many of which were brought to India around 1500 B.C.E. by the Aryans. The social stratification of the Aryan society also influenced India, and along with Hinduism, a number of social classes, called castes, simultaneously developed after the Aryans' arrival.

Just as Hinduism includes a variety of religious traditions, it also has a variety of different types of religious leaders. According to the strict interpretation of the caste system, all priests must come from the highest, or Brahman caste. Since a person is compelled to remain in the same caste into which he was born, with the possibility to be born into a higher caste at his next reincarnation, in most cases, the priesthood is hereditary. Besides the Priests, Hinduism also has ascetic monastic orders, referred to as Sannyasa, primarily from the Brahman caste. A third category of religious leaders in Hinduism are asacharya or gurus, teachers of divine personality who have come to the earth to teach by example, and to help ordinary adherents to understand the scriptures.

Since Hinduism includes a variety of gods, religious practices, and religious leaders, each person's faith is an individual matter, and each will choose a form of devotion and a spiritual leader that suits the goals and nature of his faith. All of these religious leaders have a responsibility to guide those who follow them and look to them as examples, to live and teach an upright and holy life.

The Brahman, or priestly, caste in Hinduism

The various religious traditions practiced in India and referred to as Hinduism have their roots in an ancient religion based on the Vedas, that came to India along with the invading Aryans around 1500 B.C.E. One aspect of Hinduism that is based on Aryan society is the caste system, a hierarchy of socioeconomic categories called varnas (colours), made up of priests, warriors and commoners as recorded in the Rigveda.

The Rigveda describes four varna:

- Brahmans, the priests and religious officals, teachers of the sacred knowledge of the veda.

- Rajanyas, composed of rulers and warriors.

- Vaishyas, who were farmers, merchants, traders and craftmen

People in these three varnas are permitted to study the Vedas and have the possibility to be reborn into a higher caste, eventually reaching enlightenment or Moksha.

- Shudras, the lowest caste, were not permitted to study the vedas, and had their own religion and priests.

Later another caste was added:

- Untouchables, who performed tasks too dirty for others.

The name for the priestly or Brahman caste, appears to have originally denoted the prayers of the priests, but was eventually adopted to designate the priests themselves. Brahman is often spelled Brahmin to distinguish it from another meaning of Brahman, a term referring to the Hindu concept of ultimate reality, or universal soul.

The Brahman caste has been instructed by the Hindu scriptures to devote themselves to studying the scriptures, pure conduct and spiritual growth. Although the Brahman caste is ranked the highest in the varna system, they are not the richest class. Very often members of the Rajanya caste of rulers and warriors have are wealthier. Originally the Brahman caste was instructed to subsist mainly on alms from the rest of society. In addition to studying the scriptures, Brahmans serve the Hindu society as priests, fulfilling a variety of social and religious functions.

In the Hindu concept of rebirth, the final steps toward Moksha or salvation, can only be made by members of the Brahman class. Some male members of the Brahman class join spiritual orders called Sannyasa and pursue an ascetic life of spiritual pursuit.

Still other members of the Brahman caste find spiritually calling as Gurus, or teachers. Successful Gurus may gather large followings, and sometimes form new branches of Hinduism.

Hindu priests

http://www.hindupriest.org.uk/index.html

Hindu priests take care of the temples, lead devotions in worship of Hinduism's many deities, prepare offerings, tend to holy fires, and conduct a number of rituals and ceremonies, many of them rooted deeply in the Vedic tradition. These include rituals and ceremonies pertaining to:

- Birth: Ceremonies the well-being of the mother during pregnancy to provide for the healthy development of her child, as well as ceremonies for a safe birth, and for bestowing the child's name.

- Birthdays, including special ceremonies for a child's first birthday, and coming of age.

- Marriage, including rituals that the priest performs at the family home the day before the wedding ceremony.

- Purification ceremonies for removing negative influences of newly purchased homes or other properties.

- Death: Last rites ceremonies, and other rituals to help the deceased to pass over peacefully.[1]

Sannyasa, the final stage of the varna system

Hindus who have taken vows to follow spiritual pursuits are referred to as Sannyāsa (Devanagari: संन्यास), and are members of the renounced order of life within Hinduism. This is considered the topmost and final stage of the varna and ashram systems and is traditionally taken by men at or beyond the age of fifty years old or by young monks who wish to dedicate their entire life towards spiritual pursuits. One within the sannyasa order is known as a sannyasi or sannyasin.

Etymology

Saṃnyāsa in Sanskrit means "renunciation," "abandonment." It is a tripartite compound; saṃ-, means "collective", ni- means "down" and āsa is from the root as, meaning "to throw" or "to put," so a literal translation would be "laying it all down." In dravidian languages, "sanyasi" is pronounced as "sannasi."

The Danda, or holy staff

Sannyasin sometimes carry a 'danda', a holy staff. In the Varnashrama System or Dharma of Sanatana Dharma, the 'danda' (Sanskrit; Devanagari: दंड, lit. stick) is a spiritual attribute and symbol of certain deities such as Bṛhaspati, and holy people carry the danda as an austerity and marker of their station.

Categories of sannyasi

There are a number of types of sannyasi. Traditionally there were four types, each with a different degree of religious dedication. More recently, sannyasi are more likely to be divided into just two distinct orders: "ekadanda" (literally single stick) and "tridanda' (triple rod or stick) monks. Ekadanda monks are part of the Sankaracarya tradition, and tridanda monks are part of the sannyasa discipline followed by various vaishnava traditions, which has been introduced to the west by followers of the reformer Siddhanta Sarasvati. Each of these two orders have their own traditions of austerities, attributes, and expectations.

Lifestyle and goals

The sannyasi lives a celibate life without possessions, practises yoga meditation — or in other traditions, bhakti, or devotional meditation, with prayers to their chosen deity or God. The goal of the Hindu Sannsyasin is moksha (liberation), the conception of which also varies. For the devotion oriented traditions, liberation consists of union with the Divine, while for Yoga oriented traditions, liberation is the experience of the highest samadhi (enlightenment). For the Advaita tradition, liberation is the removal of all ignorance and realising oneself as one with the Supreme Brahman. Among the 108 Upanishads of the Muktika, 23 of them are considered Sannyasa Upanishads.

Within the Bhagavad Gita, sannyasa is described by Krishna as follows:

"The giving up of activities that are based on material desire is what great learned men call the renounced order of life [sannyasa]. And giving up the results of all activities is what the wise call renunciation [tyaga]." (18.2)[2]

The term is generally used to denote a particular phase of life. In this phase of life, the person develops vairāgya, or a state of determination and detachment from material life. He renounces all worldly thoughts and desires, and spends the rest of his life in spiritual contemplation. It is the last in the four phases of a man, which are referred to as brahmacharya, grihastha, vanaprastha, and finally sannyasa, as prescribed by Manusmriti for the Dwija castes, in the Hindu system of life. These four stages are not necessarily sequential. One can skip one, two or three ashrams, but can never revert back to an earlier ashrama or phase. Various Hindu traditions allow for a man to renounce the material world from any of the first three stages of life.

Monasticism

Unlike monks in the Western world, whose lives are regulated by a monastery or an abbey and its rules, most Hindu sannyasin are loners and wanderers (parivrājaka). Hindu monasteries (mathas) never have a huge number of monks living under one roof. The monasteries exist primarily for educational purposes and have become centers of pilgrimage for the lay population. Ordination into any Hindu monastic order is purely at the discretion of the individual guru, or teacher, who should himself be an ordained sannyasi within that order. Most traditional Hindu orders do not have women sannyasis, but this situation is undergoing changes in recent times.

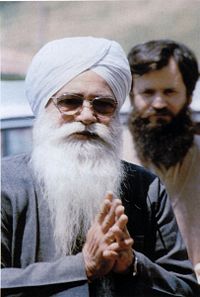

The guru-shishya tradition

Another important leadership aspect in Hinduism is the guru-shishya tradition, which places primal emphasis ont lineage, or parampara, a spiritual relationship where Hindu teachings are transmitted from a guru (teacher, गुरू) to a 'śiṣya' (disciple, शिष्य) or chela. Such knowledge, whether it be vedic, agamic artistic, architectural, musical or spiritual, is imparted through the developing relationship between the guru and the disciple. It is considered that this relationship, based on the genuineness of the guru, and the respect, commitment, devotion and obedience of the student, is the best way for subtle or advanced knowledge to be conveyed. The student eventually masters the knowledge that the guru embodies.

Historical background

Beginning in the early oral traditions of the Upanishads (c. 2000 B.C.E.), the guru-shishya relationship has evolved into a fundamental component of Hinduism. The term Upanishad derives from the Sanskrit words upa (near), ni (down) and şad (to sit) — so it means "sitting down near" a spiritual teacher to receive instruction. The relationship between Krishna and Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita portion of the Mahabharata, and between Rama and Hanuman in the Ramayana are examples. In the Upanishads, gurus and shishya appear in a variety of settings (a husband answering questions about immortality, a teenage boy being taught by Yama, the Hindu Religion's Lord of Death, etc.) Sometimes the sages are women, and the instructions may be sought by kings.

In the Vedas, the brahmavidya or knowledge of Brahman is communicated from guru to shishya by oral lore.

Common characteristics of the guru-shishya relationship

Within the broad spectrum of the Hindu religion, the guru-shishya relationship can be found in numerous variant forms including Tantra. Some common elements in this relationship include:

- The establishment of a teacher/student relationship.

- A formal recognition of this relationship, generally in a structured initiation ceremony where the guru accepts the initiate as a shishya and also accepts responsibility for the spiritual well-being and progress of the new shishya.

- Sometimes this initiation process will include the conveying of specific esoteric wisdom and/or meditation techniques.

- Gurudakshina, where the shishya gives a gift to the guru as a token of gratitude, often the only monetary or otherwise fee that the student ever gives. The traditional gift was a cow, a gift of great value, since cows are sacred to Hindus. The tradition has evolved over time, and each student chooses a gift that he feels is appropriate, which may range from a simple piece of fruit to a sizable financial donation toward the guru's work.

Parampara and Sampradaya

Traditionally word used for a succession of teachers and disciples in ancient Indian culture is parampara (paramparā in IAST).[3][4] In the parampara system, knowledge (in any field) is believed to be passed down through successive generations. The Sanskrit word literally means an uninterrupted series or succession. Sometimes defined as "the passing down of Vedic knowledge" its believed to be always entrusted to the ācāryas.[4] An established parampara is often called sampradāya, or school of thought. Fore example in Vaishnavism a number of sampradayas are developed following a single teacher, or an acharya. While some argue for freedom of interpretation others maintain that "[a]lthough an ācārya speaks according to the time and circumstance in which he appears, he upholds the original conclusion, or siddhānta, of the Vedic literature."[4]

Guru-shishya relationship types

There is a variation in the level of authority that may be granted to the guru. The highest is that found in bhakti yoga such as that in the Sathya Sai Baba movement, and the lowest is in the Pranayama forms of yoga such as the Sankara Saranam movement. Between these two there are many variations in degree and form of authority.

Advaita Vedanta

Advaita vedānta requires anyone seeking to study advaita vedānta to do so from a Guru (teacher). The Guru must have the following qualities (see Mundaka Upanishad 1.2.12):

- Śrotriya — must be learned in the Vedic scriptures and sampradaya

- Brahmanişţha — literally meaning established in Brahman; must have realised the oneness of Brahman in everything and in himself.[citation needed]

The seeker must serve the Guru and submit his questions with all humility so that doubt may be removed. (see Bhagavad Gita 4.34). According to Advaita, the seeker will be able to attain moksha (liberation from the cycle of births and deaths).

Śruti tradition

The Guru-shishya tradition plays an important part in the Shruti tradition of Vaidika dharma. The Hindus believe that the Vedas have been handed down through the ages from Guru to shishya. The Vedas themselves prescribe for a young brahmachari to be sent to a Gurukul where the Guru (referred to also as acharya) teaches the pupil the Vedas and Vedangas. The pupil is also taught the prayoga to perform yajnas. The term of stay varies (Manu Smriti says the term may be 12 years, 36 years or 48 years). After the stay at the Gurukul the brahmachari returns home after performing a ceremony called samavartana.

The word Śrauta is derived from the word Śruti meaning that which is heard. The Śrauta tradition is a purely oral handing down of the Vedas, but many modern Vedic scholars make use of books as a teaching tool.[5]

Shaktipat tradition

The guru passes his knowledge to his disciples by virtue of the fact that his purified consciousness enters into the selves of his disciples and communicates its particular characteristic. In this process the disciple is made part of the spiritual family (kula) - a family which is not based on blood relations but on people of the same knowledge.[6]

Bhakti yoga

The best known form of the Guru-shishya relationship is that of bhakti. Bhakti (Sanskrit = Devotion) means surrender to God or guru. Bhakti extends from the simplest expression of devotion to the ego-destroying principle of prapati, which is total surrender. The bhakti form of the guru-shishya relationship generally incorporates three primary beliefs or practices:

- Devotion to the guru as a divine figure or avatar.[citation needed]

- The belief that such a guru has transmitted, or will impart moksha, diksha or shaktipat to the (successful) shishya.

- The belief that if the shishya’s act of focusing his or her devotion (bhakti) upon the guru is sufficiently strong and worthy, then some form of spiritual merit will be gained by the shishya.[citation needed]

Prapatti

In the ego-destroying principle of prapatti (Sanskrit, "Throwing oneself down"), the level of the submission of the will of the shishya to the will of God or the guru is sometimes extreme, and is often coupled with an attitude of personal helplessness, self-effacement and resignation. This doctrine is perhaps best expressed in the teachings of the four Samayacharya saints, who shared a profound and mystical love of Siva expressed by:

- Deep humility and self-effacement, admission of sin and weakness;

- Total surrender to God as the only true refuge; and

- A relationship of lover and beloved known as bridal mysticism, in which the devotee is the bride and Siva the bridegroom.

In its most extreme form it sometimes includes:

- The assignment of all or many of the material possessions of the shishya to the guru.

- The strict and unconditional adherence by the shishya to all of the commands of the guru. An example is the legend that Karna silently bore the pain of a wasp stinging his thigh so as not to disturb his guru Parashurama.

- A system of various titles of implied superiority or deification which the guru assumes, and often requires the shishya to use whenever addressing the guru.

- The requirement that the shishya engage in various forms of physical demonstrations of affection towards the guru, such as bowing, kissing the hands or feet of the guru, and sometimes agreeing to various physical punishments as may sometimes be ordered by the guru.

- Sometimes the authority of the guru will extend to all aspects of the shishya's life, including sexuality, livelihood, social life, etc.

Often a guru will assert that he or she is capable of leading a shishya directly to the highest possible state of spirituality or consciousness, sometimes referred to within Hinduism as moksha. In the bhakti guru-shishya relationship the guru is often believed to have supernatural powers, leading to the deification of the guru.

Notes

- ↑ Hindu Priest.net - For the journey ahead Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ↑ Bhagavad Gita 18.2

- ↑ Bg. 4.2 evaṁ paramparā-prāptam imaṁ rājarṣayo viduḥ - This supreme science was thus received through the chain of disciplic succession, and the saintly kings understood it in that way..

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Satsvarupa, dasa Goswami (1976), Readings in Vedit Literature: The Tradition Speaks for Itself, ISBN 0912776889

- ↑ Hindu Dharma

- ↑ Abhinavagupta: The Kula Ritual, as Elaborated in Chapter 29 of the Tantrāloka, John R. Dupuche, Page 131

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dharmanidhi (1996). The Guru-Disciple System in the West in Yoga Magazine, July, 1996.

- Mansfield, Victor (1996). The Guru-Disciple Relationship: Making connections and withdrawing projections

Further reading

- Besant, Annie Wood (2003). The Path of Discipleship. Book Tree. ISBN 1-58509-216-9.

- Eugene Milne Cosgrove (2004). The High Walk of Discipleship. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 1-4179-7918-6.

- Evans-Wentz, W. Y. (2000). Tibetan Yoga and secret doctrines, or, Seven books of wisdom of the Great Path, according to the late Lāma Kazi Dawa-Samdup's English rendering. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513314-5.

- McLeod, Stuart. "The Benefits and Pitfals of the Teacher–Meditator Relationship" in Contemporary Buddhism (ISSN 1463-9947), Vol.6, No.1, May 2005, pp. 65-78. Web version (PDF) at thezensite

- Neuman, Daniel M. (1990). The life of music in north India: the organization of an artistic tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-57516-0.

end Wikipedia

The Guru in Hinduism

The nearest word in English for guru is "great." Related words in Sanskrit are Guruttar and Garishth, which have meanings similar to greater and greatest. Hinduism emphasizes the importance of finding a guru who can impart transcendental knowledge, or (vidyā). One of the main Hindu texts, the Bhagavad Gita, is a dialogue between God in the form of Krishna and his friend Arjuna, a Kshatriya prince who accepts Krishna as his guru on the battlefield, prior to a large battle. Not only does this dialogue outline many of the ideals of Hinduism, but their relationship is considered an ideal one of Guru-Shishya. In the Gita, Krishna speaks to Arjuna of the importance of finding a guru:

Acquire the transcendental knowledge from a Self-realized master by humble reverence, by sincere inquiry, and by service. The wise ones who have realized the Truth will impart the Knowledge to you. [1]

In the sense mentioned above, guru is used more or less interchangeably with satguru (literally: true teacher) and satpurusha. Compare also Swami. The disciple of a guru is called a śiṣya or chela. Often a guru lives in an ashram or in a gurukula (the guru's household), together with his disciples. The lineage of a guru, spread by disciples who carry on the guru's message, is known as the guru parampara, or disciplic succession.

Some Hindu denominations like BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha hold that a personal relationship with a living guru, revered as the embodiment of God, is essential in seeking moksha. The guru is the one who guides his or her disciple to become jivanmukta, the liberated soul able to achieve salvation in his or her lifetime.

The role of the guru continues in the original sense of the word in such Hindu traditions as the Vedānta, yoga, tantra and bhakti schools. Indeed, it is now a standard part of Hinduism that a guru is one's spiritual guide on earth. In some more mystical traditions it is believed that the guru could awaken dormant spiritual knowledge within the pupil. The act of doing this is known as shaktipat.

In Hinduism, the guru is considered a respected person with saintly qualities who enlightens the mind of his or her disciple, an educator from whom one receives the initiatory mantra, and one who instructs in rituals and religious ceremonies. The Vishnu Smriti and Manu Smriti regard the teacher and the mother and father as the most venerable influences on an individual.

Some influential gurus in the Hindu tradition were Adi Shankaracharya, Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, and Shri Ramakrishna. Other gurus who continued the yogic tradition into the 20th century include: Shri Aurobindo Ghosh, Shri Ramana Maharshi, Sathya Sai Baba, Sri Chandrashekarendra Saraswati (The Sage of Kanchi), Swami Sivananda, Paramahansa Yogananda, Swami Chinmayananda, Swami Vivekananda and A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

In Indian culture, a person without a guru or a teacher (acharya) was once looked down on as an orphan or unfortunate one. The word anatha in Sanskrit means "the one without a teacher." An acharya is the giver of gyan (knowledge) in the form of shiksha (instruction). A guru also gives diksha initiation which is the spiritual awakening of the disciple by the grace of the guru. Diksha is also considered to be the procedure of bestowing the divine powers of a guru upon the disciple, through which the disciple progresses continuously along the path to divinity.

The concept of the "guru" can be traced as far back as the early Upanishads, where the idea of the Divine Teacher on earth first manifested from its early Brahmin associations. Although gurus may have traditionally come from the Brahman class, some gurus from lower castes, including Guru Ravidass, have appeared and have become renowned teachers with many followers. [2]

Gallery

- Ravidaskijai.JPG

Guru Ravidas, Indian Hindu religious leader and founder Satguru of the Ravidasi beliefs, revered by most Hindus as a Sant

- Hindu priest altar.jpg

A Hindu priest makes preparations at the alter before a wedding.

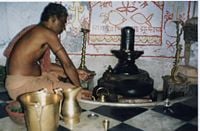

- Brahman priest speaking.jpg

A Brahman priest leading a yagna puja ritual.

See also

- Hinduism

- Islamic religious leaders

- Holy orders

- Caste system

- Dharma transmission

- Gurukula

- Satguru

- Shaktipat

Notes

- ↑ Bhagavad Gita, c4 s34

- ↑ Sri Guru Ravi Das ji website. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

References

- Case, Margaret H. Seeing Krishna: the religious world of a Brahman family in Vrindaban. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780195130119

- Jagannātha Dīkṣita Cipol̲aṇakara, and H. G. Ranade. Brahmatva-mañjarī = Brahmatva-mañjarī : role of the Brahman priest in the Vedic ritual. Ranade publication series, no. 3. Poona: H.G. Ranade, 1984. OCLC: 15487624

- Barnes, Michael, Margaret Hebblethwaite, and Peter Hebblethwaite. Traditions of spiritual guidance: the guru in Hinduism. London: The Way, 1984. OCLC: 128292184

- Pechilis, Karen. The graceful guru: Hindu female gurus in India and the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780195145380

- Thekkudan, Anto P. Sannyasa And Spiritual Formation in Hinduism. Alwaye, India: St. Thomas Academy for Research, 1988.

- Abhishiktananda. The further shore: Sannyasa and the Upanishads, an introduction : two essays. Delhi: I.S.P.C.K., 1975, OCLC: 2929851

External links

All links retrieved October 7, 2008.

- Articles on aspects of Sannyasa, Vairagya, and Brahmacharya

- 'The Song of the Sannyasin', poem by Swami Vivekananda

- The Internal Meaning of Sannyasa

- The concept of a Brahman

- Encyclopedia for Epics of Ancient India: Brahman

- HinduPriest.net-For the journey ahead

- HinduPriest.org

- Hindu Guru

- Scriptures and Gurus: Sources of Authority

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.