Hindu leadership

Material from Holy Orders

The caste system and Hinduism

Hinduism is an umbrella term for various religious traditions practiced in India. It is based on an ancient religion, the Veda. The Veda was brought in India along with the invasion of the Aryans in the North West part of India around 1500 B.C.E. To understanding the current holy order in Hinduism, it is helpful to understand the origins of Hinduism and its most ancient text, the Vedas. Aryan society, who brought the Vedas, was divided into a hierarchy made up of priests, warriors and commoners. That social stratification was adapted as they conquered new lands and more population were integrated into their society. The Rigveda recorded an ancient tradition of socioeconomic categories called varnas (colours). When the Aryans first encountered the dark-skinned people of North western India they called called them daha (enemy) or darsa( servant), and the people of these tribes came to occupy a new class of servant in the Aryan society.

Hymn 10.9 of the Rigveda, states that humanity emerged in the form of four varna from the self sacrificial rite of Purusha (the primal man). From the mouth of Purusha was made the Brahmans, from his arms was made the Rajanyas (later renamed Kshatriva), from his two thighs was made the Vaishyas and from his feet were born the Shudras. Member of the brahmins, rajanis and Vaishyanis group constituted the upper varnas and the Aryan invader were the members of these varnas. The darsa were members of the shudras, the lowest lower varna. Brahmans were the priests and religious officials. They were the teachers of the veda, the sacred knowledge. The kshatriva were composed of rulers and warriors and the vaishva was composed of farmers, merchants, traders and craftmen. By virtue of their Aryan descent, the members of the upper varna can reach the status of dvija (twice born). The term twice born refers to the fact that the males of these varnas pass through the upanayana, a ceremony to enter into Aryan adulthood, when they reach 12 years of age. Upon completion of that ceremony, the young boy is considered fit to receive sacred knowledge and participate in specified sacraments. He is reborn as a Hindu.

The members of the shrudra varna, since they were not from Aryan descent did not participate in the ceremony of rebirth. Furthermore, they were not allowed to participate in the Vedic rites with the upper caste and did not have the privilege to study and read the Veda. They had their own priests and religious rites.

When the Aryans expanded their conquest further into India, they met new communities. To accommodate the social structure of their society, another stratum was added, below the shudra, the untouchables. The members of the untouchables perform tasks considered dirty by the rest of society, such as latrine cleaner. Because of their high level of “impurity” they were segregated in hamlets outside the town or village boundary. They were forbidden entry to many temples, schools and wells from which the higher castes drew water. These practices continue even today, especially in rural areas.

It is believed by some scholars that membership in a varna was primarily based on ones occupation. It is however customarily accepted in Indian society that membership in a varna is primarily through birth, thus the existence of the notion of jati or caste. Hence, varna has slowly become synonym with caste.

The relationship between the members of castes is highly regulated around the notion of purity and impurity. The higher castes are considered more pure and strive to maintain their purity. The lower castes are considered as source of impurity. For one to alter his/her purity level is mainly through four medium: marriage, drink, food and touch. For a member of a higher caste who was contaminated with the impurity of a lower caste to gain back his/her status, he has to pass through rite of purification.

Social mobility within the varna is not theoretically possible during ones lifetime. For a lower varna to move up the ladder, he should be a devoted and good member of the varna and wait to be reborn after death in a higher varna. However some individuals succeeded in integration a higher varna during their lifetime.

They succeed mainly through emulating the higher caste and taking their habits of conduct. When this is combined with some form of power over the higher caste, the mobility is more easily accomplished. An untouchable for example, to emulate the Shudra will take on the Shudra dressing and dietetic code. He will also strive to avoid performing work the Sudra see as impure. All these effort will be deem successful if for example, the Shudra agree to eat a meal cooked by him.

This kind of mobility is usually between two closely ranked castes. An untouchable will hardly seek to rise from is level to the level of Brahman. It is this process of raising up to the varna ladder and being accepted by the higher caste that was one of the main factors in the spread of Hinduism among the population of south western Asia.

The caste system, even though it is viewed as a fundamental ingredient of Indian society is criticized by many Hindu scholars who are seeking for its adaptation to modern time. The untouchables, who are the lowest caste because of the burden put upon them by the varna system, usually seek refuge in religions were there is no legal caste system. Hence the easy conversion of those from this low caste to Buddhism, Christianity and Islam. The notion of untouchability was declared illegal in the constitution of India of 1949 and that of Pakistan in 1953. However, the varna system is still strong in rural areas and many of the untouchables are still struggling to improve their civil rights and recognition.

Sannyasa, the final stage of the varna system

Sannyasa, (Devanagari: संन्यास) sannyāsa is the renounced order of life within Hinduism. It is considered the topmost and final stage of the varna and ashram systems and is traditionally taken by men at or beyond the age of fifty years old or by young monks who wish to dedicate their entire life towards spiritual pursuits. One within the sannyasa order is known as a sannyasi or sannyasin.

Etymology

Saṃnyāsa in Sanskrit means "renunciation", "abandonment". It is a tripartite compound of saṃ- has "collective" meaning, ni- means "down" and āsa is from the root as, meaning "to throw" or "to put", so a literal translation would be "laying it all down". In dravidian languages, "sanyasi" is pronounced as "sannasi".

Danda as spiritual attribute

In the Varnashrama System or Dharma of Sanatana Dharma, the 'danda', a holy staff, (Sanskrit; Devanagari: दंड, lit. stick) is a spiritual attribute and axis mundi of certain deities such as Bṛhaspati, and holy people such as sadhu carry the danda as an austerity and marker of their station as a mendicant renunciate or sannyasin.

Categories of sannyasi

There are a number of types of sannyasi in accordance with socio-religious context. Traditionally there were four types with different stages of dedication. In recent times, sannyasi are more likely to be divided into two distinct orders: "ekadanda" (literally single stick) and "tridanda' (triple rod or stick) monks. The former are part of the Sankaracarya tradition, and the second is the sannyasa discipline followed by various vaishnava traditions and introduced to the west by followers of the reformer Siddhanta Sarasvati. The two orders each have their own traditions of austerities, attributes, and expectations.

Lifestyle and goals

The sannyasi lives a celibate life without possessions, practises yoga meditation — or in other traditions, bhakti, or devotional meditation, with prayers to their chosen deity or God. The goal of the Hindu Sannsyasin is moksha (liberation), the conception of which also varies. For the devotion oriented traditions, liberation consists of union with the Divine, while for Yoga oriented traditions, liberation is the experience of the highest samadhi (enlightenment). For the Advaita tradition, liberation is the removal of all ignorance and realising oneself as one with the Supreme Brahman. Of the 108 Upanishads of the Muktika, 23 are considered Sannyasa Upanishads.

Within the Bhagavad Gita, sannyasa is described by Krishna as follows:

"The giving up of activities that are based on material desire is what great learned men call the renounced order of life [sannyasa]. And giving up the results of all activities is what the wise call renunciation [tyaga]." (18.2)[1]

The term is generally used to denote a particular phase of life. In this phase of life, the person develops vairāgya, or a state of determination and detachment from material life. He renounces all worldly thoughts and desires, and spends the rest of his life in spiritual contemplation. It is the last in the four phases of a man, namely, brahmacharya, grihastha, vanaprastha, and finally sannyasa, as prescribed by Manusmriti for the Dwija castes, in the Hindu system of life. However, these four stages are not necessarily sequential, but on the other hand can not be reversed, in other sense they are progressive phases, one can skip one, two or three ashrams, but can never revert back to an earlier ashrama or phase. Various Hindu traditions allow for a man to renounce the material world from any of the first three stages of life.

Monasticism

Unlike monks in the Western world, whose lives are regulated by a monastery or an abbey and its rules, some Hindu sannyasin are loners and wanderers (parivrājaka). Hindu monasteries (mathas) never have a huge number of monks living under one roof. The monasteries exist primarily for educational purposes and have become centers of pilgrimage for the lay population. Ordination into any Hindu monastic order is purely at the discretion of the individual guru, or teacher, who should himself be an ordained sannyasi within that order. Most traditional Hindu orders do not have women sannyasis, but this situation is undergoing changes in recent times.

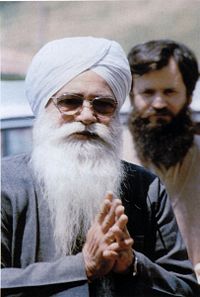

- Ravidaskijai.JPG

Guru Ravidas, Indian Hindu religious leader and founder Satguru of the Ravidasi beliefs, revered by most Hindus as a Sant

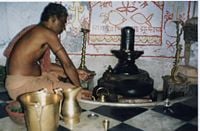

- Hindu priest altar.jpg

A Hindu priest makes preparations at the alter before a wedding.

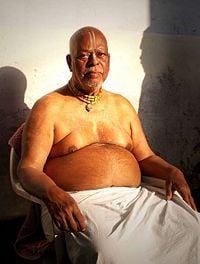

- Brahman priest speaking.jpg

A Brahman priest leading a yagna puja ritual.

Material from Wikipedia Sannyasa

- "Sanyasi" redirects here. For the motion picture, see Sanyasi (1975 film)

Sannyasa, (Devanagari: संन्यास) sannyāsa is the renounced order of life within Hinduism. It is considered the topmost and final stage of the varna and ashram systems and is traditionally taken by men at or beyond the age of fifty years old or by young monks who wish to dedicate their entire life towards spiritual pursuits. One within the sannyasa order is known as a sannyasi or sannyasin.

Etymology

Saṃnyāsa in Sanskrit means "renunciation", "abandonment". It is a tripartite compound of saṃ- has "collective" meaning, ni- means "down" and āsa is from the root as, meaning "to throw" or "to put", so a literal translation would be "laying it all down". In Dravidian languages, "sanyasi" is pronounced as "sannasi".

Typology

There are a number of types of sannyasi in accordance with socio-religious context. Traditionally there are four types of forest hermits [2] with different stages of dedication. In recent history two distinct orders are observed "ekadanda" (literally single stick) and "tridanda' (triple rod or stick) saffron robed monks[3], first being part of Sankaracarya tradition[4] second is sannyasa followed by various vaishnava traditions and introduced to the west by followers of the reformer Siddhanta Sarasvati. Austerities and attributes associated with the order as well as expectations will differ in both.

Lifestyle and goals

The sannyasi lives a celibate life without possessions, practises yoga meditation — or in other traditions, bhakti, or devotional meditation, with prayers to their chosen deity or God. The goal of the Hindu Sannsyasin is moksha (liberation), the conception of which also varies. For the devotion oriented traditions, liberation consists of union with the Divine, while for Yoga oriented traditions, liberation is the experience of the highest samadhi (enlightenment). For the Advaita tradition, liberation is the removal of all ignorance and realising oneself as one with the Supreme Brahman.

Within the Bhagavad Gita, sannyasa is described by Krishna as follows:

"The giving up of activities that are based on material desire is what great learned men call the renounced order of life [sannyasa]. And giving up the results of all activities is what the wise call renunciation [tyaga]." (18.2)[5]

Application

The term is generally used to denote a particular phase of life. In this phase of life, the person develops vairāgya, or a state of determination and detachment from material life. He renounces all worldly thoughts and desires, and spends the rest of his life in spiritual contemplation. It is the last in the four phases of a man, namely, brahmacharya, grihastha, vanaprastha, and finally sannyasa, as prescribed by Manusmriti for the Dwija castes, in the Hindu system of life. However, these four stages are not necessarily sequential, but on the other hand can not be reversed, in other sense they are progressive phases, one can skip one, two or three ashrams, but can never revert back to an earlier ashrama or phase. Various Hindu traditions allow for a man to renounce the material world from any of the first three stages of life.

Monasticism

Unlike monks in the Western world, whose lives are regulated by a monastery or an abbey and its rules, some Hindu sannyasin are loners and wanderers (parivrājaka). Hindu monasteries (mathas) never have a huge number of monks living under one roof. The monasteries exist primarily for educational purposes and have become centers of pilgrimage for the lay population. Ordination into any Hindu monastic order is purely at the discretion of the individual guru, who should himself be an ordained sannyasi within that order. Most traditional Hindu orders do not have women sannyasis, but this situation is undergoing changes in recent times.[citation needed]

Danda as spiritual attribute

In the Varnashrama System or Dharma of Sanatana Dharma, the 'danda' (Sanskrit; Devanagari: दंड, lit. stick) is a spiritual attribute and axis mundi of certain deities such as Bṛhaspati, and holy people such as sadhu carry the danda as an austerity and marker of their station as a mendicant renunciate or sannyasin.

Sannyasa Upanishads

Of the 108 Upanishads of the Muktika, 23 are considered Sannyasa Upanishads.[6] They are listed with their associated Veda – ṚV, SV, ŚYV, KYV, AV (as found in the Upanishad):

- Brahma (KYV)

- Jābāla (ŚYV)

- Śvetāśvatara (KYV) "The Faces of God"

- Āruṇeya (SV)

- Garbha (KYV)

- Paramahaṃsa (ŚYV)

- Maitrāyaṇi (SV)

- Maitreyi (SV)

- Tejobindu (KYV)

- Parivrāt (Nāradaparivrājaka) (AV)

- Nirvāṇa (ṚV)

- Advayatāraka (ŚYV)

- Bhikṣu (SYV)

- Turīyātīta (SYV)

- Sannyāsa (SV)

- Paramahaṃsaparivrājaka (AV)

- Kuṇḍika (SV)

- Parabrahma (AV)

- Avadhūta (KYV)

- Kaṭharudra (KYV)

- Yājñavalkya (SYV)

- Varāha (KYV)

- Śāṭyāyani (SYV)