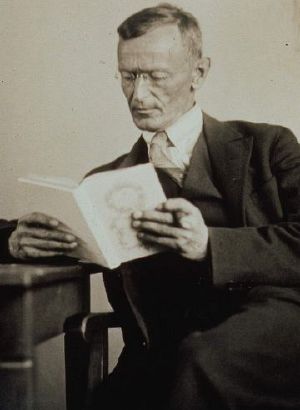

Hermann Hesse

Hermann Hesse ([ˈhɛr.man ˈhɛ̞.sɘ]) (2 July 1877 – 9 August 1962) was a German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter, considered to be one of the most impotant European writers of the first half of the 20th-century. During Hesse's long life he participated in a number of crucial moments in literary and human history. As a young man in the late 19th-century he was an eager student of the 19th-century's Romanticism, and while he would later outgrow these youthful tendencies, his works are tinged with Romantic ideas, and Hesse himself admitted his immense debt to major Romantic novelists and poets such as Goethe and Hölderlin.

Hesse, however, spent much of his maturity as an author in the period known as Modernism that dominated the early decades of the 20th-century. Although Hesse collaborated closely with a number of modern writers, among them Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht, he was never himself a very typical Modernist: his prose is not nearly as baffling or experimental as many other authors of his time; in fact, Hesse's novels are often used by students of the German language because they are written in such an accesible style. Hesse was concerned with the dominant themes of modernism—finding meaning in an increasingly meaningless world; the erosion of standards and the past—and he expressed his interest not in the form of his novels but in their content.

Hesse also, unlike a number of the other major luminaries of the Modernism, also lived to see the end of the Second World War. Having survived that disaster, and being faced with the formidable task of writing fiction in its aftermath, he produced what is often believed to be his most ambitious work of all: Das Glasperlenspiel (The Glass Bead Game). As Modernism faded away and the world moved forward into the present, Hesse continued to write and act as a major literary figure. Hesse had been an early opponent of National Socialism—he came close to losing his freedom and possibly even his life due to his criticism of the Third Reich—and he has become, to the German people and to the world at large, a symbol of a brilliant mind that lived through one of the worst events in history, and still endured. To say that Hesse's reputation has grown to heroic proportions may be only slight exaggeration; to say that he is one of the most important novelists to have emerged from Germany is most certainly not exaggeration at all.

Life

Youth

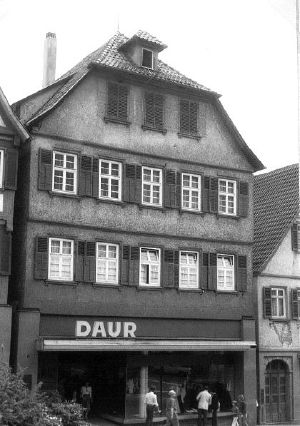

Hermann Hesse was born on July 2, 1877 in the Black Forest town of Calw in Württemberg, Germany to a Christian Missionary family. Both of his parents served with a Basel Mission to India, where Hesse's mother Marie Gundert was born in 1842. Hesse's father, Johannes Hesse, was born in 1847 in Estonia as the son of a doctor. The Hesse family had lived in Calw since 1873, where they operated a missionary publishing house under the direction of Hesse's grandfather, Hermann Gundert.

Hermann Hesse spent his first years of life surrounded by the spirit of Swabian piety. In 1881 the family moved to Basel, Switzerland for five years, then returned to Calw. After successful attendance at the Latin School in Göppingen, Hesse began to attend the Evangelical Theological Seminary in Maulbronn in 1891. Here in March 1892, Hesse showed his rebellious character: he fled from the Seminary and was found in a field a day later.

During this time, Hesse began a journey through various institutions and schools, and experienced intense conflicts with his parents. It was also at about this time that his bipolar disorder began to affect him, and he mentioned suicidal thoughts in a letter from March 20, 1892. In May, after an attempt at suicide, he spent time at an institution in Bad Boll under the care of theologian and minister Christoph Friedrich Blumhardt. Later he was placed in a mental institution in Stetten im Remstal, and then a boys' institution in Basel.

At the end of 1892, he attended the Gymnasium in Cannstatt. In 1893, he passed the One Year Examination, which concluded his schooling.

After this, he began a bookshop apprenticeship in Esslingen am Neckar, but after three days he left. Then in the early summer of 1894, he began a fourteen month mechanic apprenticeship at a clock tower factory in Calw. The monotony of soldering and filing work made him resolve to turn himself toward more spiritual activities. In October 1895, he was ready to begin wholeheartedly a new apprenticeship with a bookseller in Tübingen. This experience from his youth he returns to later in his novel, Beneath the Wheel.

Toward a writer

On October 17, 1895, Hesse began working in the bookshop Heckenhauer in Tübingen, which had a collection specializing in theology, philology, and law. Hesse's assignment there consisted of organizing, packing, and archiving the books. After the end of each twelve hour workday, Hesse pursued his own work further, and he used his long, free Sundays with books rather than social contacts. Hesse studied theological writings, and later Goethe, Lessing, Schiller, and several texts on Greek mythology. In 1896, his poem 'Madonna' appeared in a Viennese periodical.

In 1898, Hesse had a respectable income that enabled his financial independence from his parents. During this time, he concentrated on the works of the German Romantics, including much of the work from Clemens Brentano, Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, Friedrich Holderlin and Novalis. In letters to his parents, he expressed a belief that "the morality of artists is replaced by aesthetics."

In the fall, Hesse released his first small volume of poetry, Romantic Songs and in the summer of 1899, a collection of prose, entitled One Hour After Midnight. Both works were a business failure. In two years, only 54 of the 600 printed copies of Romantic Songs were sold, and One Hour After Midnight received only one printing and sold sluggishly. Nevertheless, the Leipzig publisher Eugen Diederichs was convinced of the literary quality of the work and from the beginning regarded the publications more as encouragement of a young author than as profitable business.

Beginning in the fall of 1899, Hesse worked in a distinguished antique book shop in Basel. There the contacts of his family with the intellectual families of Basel helped open for him a spiritual-artistic environment with rich stimuli for his pursuits. At the same time, Basel offered the solitary Hesse many opportunities for withdrawal into a private life of artistic self-exploration through journeys and wanderings. In 1900, Hesse was exempted from compulsory military service due to an eye condition, which, along with nerve disorders and persistent headaches, affected him his entire life.

In 1901, Hesse undertook to fulfill a grand dream and travelled for the first time to Italy. In the same year, Hesse changed jobs and began working at the antiquarium Wattenwyl in Basel. Hesse had more opportunities to release poems and small literary texts to journals. These publications now provided honorariums. Shortly the publisher Samuel Fischer became interested in Hesse, and with the novel Peter Camenzind, which appeared first as a pre-publication in 1903 and then as a regular printing by Fischer in 1904, came a breakthrough: From now on, Hesse could live as a free author.

Between Lake Constance and India

With the literary fame, Hesse married Maria Bernoulli in 1904, settled down with her in Gaienhofen on Lake Constance, and began a family, eventually having three sons. In Gaienhofen, he wrote his second novel Beneath the Wheel, which appeared in 1906. In the following time he composed primarily short stories and poems. His next novel, Gertrude, published in 1910, revealed a production crisis — he had to struggle through writing it, and he later would describe it as "a miscarriage."

Gaienhofen was also the place where Hesse's interest in Buddhism was resparked. After a letter to Kapff in 1895 entitled Nirwana, Hesse's Buddhist references were no longer alluded to in his works. This was rekindled, however, in 1904 when Arthur Schopenhauer and his philosophical ideas started receiving attention again, and Hesse discovered theosophy. Schopenhauer and theosophy are what renewed Hesse's interest in India. Although 1904 was many years before the publication of Hesse's Siddhartha (1922), this masterpiece was derived from these new influences.

During this time, there also was increased dissonance between him and Maria, and in 1911, Hesse left alone for a long trip to Sri Lanka and Indonesia. Any spiritual or religious inspiration, for which he hoped, did not find him, but the journey made a strong impression on his literary work. Following Hesse's return, the family moved to Bern in 1912, but the change of environment could not solve the marriage problems, as he himself confessed in his novel Rosshalde from 1914.

The First World War

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Hesse registered himself as a voluntary with the German government, saying that he could not sit inactively by a warm fireplace while other young authors were dying on the front. He was found unfit for combat duty, but was assigned to service involving the care of war prisoners.

On November 3, 1914 in the Neuen Züricher Zeitung, Hesse's essay O Friends, Not These Tones (O Freunde, nicht diese Töne) appeared, in which he appealed to German intellectuals not to fall for nationalism. What followed from this, Hesse later indicated, was a great turning point in his life: For the first time he found himself in the middle of a serious political conflict, attacked by the German press, the recipient of hate mail, and distanced from old friends. He did receive continued support from his friend Theodor Heuss, and also from the French writer Romain Rolland, whom Hesse visited in August 1915.

This public controversy was not yet resolved, when a deeper life crisis befell Hesse with the death of his father on March 8, 1916, the difficult sickness of his son Martin, and his wife's schizophrenia. He was forced to leave his military service and begin receiving psychotherapy. This began for Hesse a long preoccupation with psychoanalysis, through which he came to know Carl Jung personally, and was challenged to new creative heights: During a three-week period during September and October 1917, Hesse penned his novel Demian, which would be published following the armistice in 1919 under the pseudonym Emil Sinclair.

Casa Camuzzi

When Hesse returned to civilian life in 1919, his marriage was shattered. His wife had a severe outbreak of psychosis, but even after her recovery, Hesse saw no possible future with her. Their home in Bern was divided, and Hesse resettled alone in the middle of April in Ticino, where he occupied a small farm house near Minusio bei Locarno, and later lived from April 25 until May 11 in Sorengo. On May 11, he moved to the town Montagnola and rented four small rooms in a strange castle-like building, the 'Casa Camuzzi'.

Here he explored his writing projects further; he began to paint, an activity which is reflected in his next major story Klingsor's Last Summer, published in 1920. In 1922, Hesse's novel Siddhartha appeared, which showed the love for Indian culture and Buddhist philosophy, which had already developed at his parent's house. In 1924, Hesse married the singer Ruth Wenger, the daughter of the Swiss writer Lisa Wenger and aunt of Meret Oppenheim. This marriage never attained any true stability, however.

In this year, Hesse received Swiss citizenship. His next major works, Kurgast from 1925 and The Nuremberg Trip from 1927, were autobiographical narratives with ironic undertones, and which foreshadow Hesse's following novel, Steppenwolf, which was published in 1927. In the year of his 50th birthday, the first biography of Hesse appeared, written by his friend Hugo Ball. Shortly after his new successful novel, he turned away from the solitude of Steppenwolf and married a Jewish woman, Ninon Dolbin Ausländer. This change to companionship was reflected in the novel Narcissus and Goldmund, appearing in 1930.

In 1931, Hesse left the Casa Camuzzi and moved with Ninon to a large house (Casa Hesse) near Montagnola, which was built according to his wishes.

The Glass Bead Game

In 1931, Hesse began planning what would become his last major work, The Glass Bead Game. In 1932 as a preliminary study, he released the novella, Journey to the East. Hesse observed the rise to power of Nazism in Germany with concern. In 1933, Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann made their travels in exile, and in both cases, were aided by Hesse. In this way, Hesse attempted to work against Hitler's suppression of art and literature that protested Nazi ideology.

Since the 1910s, he had published book reviews in the German press, and now he spoke publicly in support of Jewish artists and others pursued by the Nazis. However, when he wrote for the Frankfurter Zeitung, he was accused of supporting the Nazis, whom Hesse did not openly oppose. From the end of the 1930s, German journals stopped publishing Hesse's work, and his work was eventually banned. As spiritual refuge from these political conflicts and later from the horror of the Second World War, he worked on the novel The Glass Bead Game which was printed in 1943 in Switzerland. For this work among his others, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946.

After WWII, Hesse's productivity declined. He wrote short stories and poems, but no more novels. He occupied himself with the steady stream of letters he received as a result of the prize and as a new generation of German readers explored his work. He died on August 9, 1962 and was buried in the cemetery at San Abbondio in Montagnola, where Hugo Ball is also buried.

Works

- 1898 - Romantische Lieder (Romantic Songs)

- 1899 - Eine Stunde hinter Mitternacht (One Hour After Midnight)

- 1904 - Peter Camenzind

- 1906 - Unterm Rad (Beneath the Wheel)

- 1908 - Freunde (Friends)

- 1910 - Gertrud (Gertrude)

- 1914 - Rosshalde

- 1915 - Knulp

- 1919 - Demian

- 1919 - Klein und Wagner (Klein and Wagner)

- 1919 - Märchen (Strange News from Another Star, short stories)

- 1920 - Blick ins Chaos (In Sight of Chaos, essays)

- 1920 - Klingsors letzter Sommer (Klingsor's Last Summer, three novellas)

- 1922 - Siddhartha

- 1927 - Die Nürnberger Reise

- 1927 - Der Steppenwolf (Steppenwolf)

- 1930 - Narziss und Goldmund (Narcissus and Goldmund)

- 1932 - Die Morgenlandfahrt (Journey to the East)

- 1937 - Gedenkblätter (Autobiographical Writings)

- 1942 - Stufen (Stages)

- 1942 - Die Gedichte (Poems)

- 1943 - Das Glasperlenspiel (The Glass Bead Game, also published as Magister Ludi)

- 1946 - Krieg und Frieden (If the War Goes On ...)

- 1976 - My Belief: Essays on Life and Art

- 1995 - The Complete Fairy Tales of Hermann Hesse

Awards

- 1906 - Bauernfeld-Preis

- 1928 - Mejstrik-Preis der Wiener Schiller-Stiftung

- 1936 - Gottfried-Keller-Preis

- 1946 - Goethepreis der Stadt Frankfurt

- 1946 - Nobel Prize in Literature

- 1947 - Honorary Doctorate from the University of Bern

- 1950 - Wilhelm-Raabe-Preis

- 1954 - Orden Pour le mérite für Wissenschaft und Künste

- 1955 - Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

Hesse received honorary citizenship from his home city of Calw, and additionally, throughout Germany many schools are named after him. In 1964, the Calwer Hermann-Hesse-Preis was founded, which is awarded every two years, alternately to a German-language literary journal or to the translator of Hesse's work to a foreign language. There is also a Hermann-Hesse-Preis that is associated with the city of Karlsruhe.

External links

- Works by Hermann Hesse. Project Gutenberg

- Hermann Hesse Page - in German and English, maintained by Professor Gunther Gottschalk

- Hermann Hesse Portal

- Community of the Journeyer to the Easy - in German and English

- Concise Biography - originally published by the Germanic American Institute, by Paul A. Schons

- Article at 'Books and Writers'

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.