Henry V of England

| Henry V | ||

|---|---|---|

| By the Grace of God, King of England,

Heir and Regent of the Kingdom of France and Lord of Ireland | ||

| ||

| Reign | 21 March 1413 - 31 August 1422 | |

| Coronation | 1413 | |

| Born | September 16 1387 | |

| Monmouth, Wales | ||

| Died | 31 August 1422 (aged 34) | |

| Bois de Vincennes, France | ||

| Buried | Westminster Abbey | |

| Predecessor | Henry IV | |

| Successor | Henry VI | |

| Consort | Catherine of Valois (1401-1437) | |

| Issue | Henry VI (1421-1471) | |

| Royal House | Lancaster | |

| Father | Henry IV (1367-1413) | |

| Mother | Mary de Bohun (c. 1369-1394) | |

Henry V of England (September 16, 1387 – August 31, 1422) was one of the great warrior kings of the Middle Ages. He was born at Monmouth, Wales, September 16, 1387, and he reigned as King of England from 1413 to 1422.

Henry was son of Henry of Bolingbroke, later Henry IV, and Mary de Bohun, who died before Bolingbroke became king.

At the time of his birth during the reign of Richard II, Henry was fairly far removed from the throne. By the time Henry died, he had not only consolidated power as the King of England but had also effectively accomplished what generations of his ancestors had failed to achieve through decades of war: unification of the crowns of England and France in a single person.

Early accomplishments and struggle in Wales

In 1398 when Henry was twelve his father, Henry Bolingbroke, was exiled by King Richard II, who took the boy into his own charge, treated him kindly and took him on a visit to Ireland. In 1399, the exiled Bolingbroke, heir to the Dukedom of Lancaster, returned to reclaim his lands. He raised an army and marched to meet the King. Richard hurried back from Ireland to deal with him. They met in Wales to discuss the restitution of Bolingbroke's lands. Whatever was intended, the meeting ended with Richard being arrested, deposed and imprisoned. He later died in mysterious circumstances. The young Henry was recalled from Ireland into prominence as heir to the Kingdom of England. He was created Prince of Wales on the day of his father's coronation as Henry IV. He was also made Duke of Lancaster, the third person to hold the title that year. His other titles were Duke of Cornwall, Earl of Chester and Duke of Aquitaine in France.

The Welsh revolt of Owain Glyndŵr (Owen Glendower) started soon after Henry IV was crowned. Richard II had been popular in Wales as he had created new opportunities for Welsh people to advance. This changed under Henry IV and Owen was one of the people who was unfairly treated by the new King. So in 1400 Glendower was proclaimed Prince of Wales. His campaign was very popular and soon much of Wales was in revolt. Owen had a vision of an independent Wales with its own partliament, church and universities. In response Henry IV invaded Wales but without success. So Henry appointed the legendary warrior Harry Hotspur to bring order to Wales. Hotspur favored negotiation with Glendower and argued that it was Henry's merciless policies that were encouraging the revolt. When the situation worsened Hotspur defected to Glendower's camp and challenged the young Henry's right to inherit the throne. Henry met Hotspur at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403 and defeated him. It was there that the sixteen-year-old prince was almost killed by an arrow which became lodged in his face. Henry had the benefit of the best possible care with the royal physician crafting a special tool to extract the tip of the arrow so as to do no further damage. The operation was successful although it probably gave the prince permanent scars which would have served as a testimony to his experience in battle.

Henry continued to fight the Welsh and introduced tactics of economic blockades. Despite considerable assistance from France the rebellion foundered in 1407 and Owen became a hunted man. However, when his father Henry IV died in 1413, Henry began to adopt a conciliatory attitude to the Welsh. Pardons were offered to the major leaders of the revolt. In 1415 Henry V offered a pardon to Owain and there is evidence that the new King Henry was in negotiations with Owen's son, Maredudd, but nothing was to come of it. In 1416 Maredudd was offered a pardon but refused. Perhaps his father was still alive and he was unwilling to accept the pardon while he lived. He finally accepted a pardon in 1421, suggesting that Owen was dead.

Role in government and conflict with Henry IV

As a result of the King's ill-health, Henry began to take a wider role in politics. From January 1410, helped by his uncles Henry and Thomas Beaufort he had practical control of the government.

However, in both foreign and domestic policy he differed from the King who, in November 1411, discharged the Prince from the council. The quarrel of father and son was political only, though it is probable that the Beauforts had discussed the abdication of Henry IV, and their opponents certainly endeavored to defame the prince. It may be to that political enmity that the tradition of Henry's riotous youth, immortalized by Shakespeare, is partly due. Henry's record of involvement in war and politics, even in his youth, disproves this tradition.

The story of Falstaff originated partly in Henry's early friendship with Sir John Oldcastle. That friendship, and the prince's political opposition to Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, perhaps encouraged Lollard hopes. If so, their disappointment may account for the statements of ecclesiastical writers, like Thomas Walsingham, that Henry on becoming king was changed suddenly into a new man.

Accession to the throne

After his father Henry IV died on March 20, 1413, Henry V succeeded him and was crowned on 9 April 1413. With no past to embarrass him, and with no dangerous rivals, his practical experience had full scope. He had to deal with three main problems - the restoration of domestic peace, the healing of schism in the Church and the recovery of English prestige in Europe. Henry grasped them all together, and gradually built upon them a yet wider policy.

Domestic policy

From the outset, he made it clear that he would rule England as the head of a united nation, and that past differences were to be forgotten. As an act of penance for the usurption of the throne by his father, Henry had the late king, Richard II, honorably reinterred in Westminster Abbey. The young Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, whose father had supported Owen Glendower, was taken into favor. The heirs of those who had suffered in the last reign were restored gradually to their titles and estates. The gravest domestic danger was Lollard discontent. But the king's firmness nipped the movement in the bud (January 1414), and made his own position as ruler secure.

With the exception of the Southampton Plot in favor of Mortimer, involving Henry Scrope, 3rd Baron Scrope of Masham and Richard, Earl of Cambridge (grandfather of the future King Edward IV of England) in July 1415, the rest of his reign was free from serious trouble at home.

Foreign affairs

Henry could now turn his attention to foreign affairs. A writer of the next generation was the first to allege that Henry was encouraged by ecclesiastical statesmen to enter into the French war as a means of diverting attention from home troubles. This story seems to have no foundation. Old commercial disputes and the support which the French had lent to Owen Glendower were used as an excuse for war, whilst the disordered state of France afforded no security for peace. The French king, Charles VI, was prone to mental illness, and his eldest son an unpromising prospect.

Campaigns in France

Henry may have regarded the assertion of his own claims as part of his Kingly duty, but in any case a permanent settlement of the national debate was essential to the success of his world policy.

- 1415 campaign

Henry V invaded France for several reasons. He hoped that by fighting a popular foreign war, he would strengthen his position at home. He wanted to improve his finances by gaining revenue-producing lands. He also wanted to take nobles prisoner either for ransom or to extort money from the French king in exchange for their return. Evidence also suggests that several lords in the region of Normandy promised Henry their lands when they died, but the King of France confiscated their lands instead.

Henry's army landed in northern France on August 13, 1415 and besieged the port of Harfleur with an army of about twelve thousand. The siege took longer than expected. The town surrendered on September 22, and the English army did not leave until October 8. The campaign season was coming to an end, and the English army had suffered many casualties through disease. Henry decided to move most of his army (roughly seven thousand) to the port of Calais, the only English stronghold in northern France, where they could re-equip over the winter.

During the siege, the French had been able to call up a large feudal army which the Constable of France, Charles d'Albret, deployed between Harfleur and Calais, mirroring the English manoeuvres along the River Somme, thus preventing them from reaching Calais without a major confrontation. The result was that d'Albret managed to force Henry into fighting a battle that, given the state of his army, Henry would have preferred to avoid. The English had very little food, had marched 260 miles in two and a half weeks, were suffering from sickness such as dysentery, and faced large numbers of experienced, well equipped Frenchmen. Although the lack of reliable and consistent sources makes it very difficult to accurately estimate the numbers on both sides, estimates vary from 6,000 to 9,000 for the English, and from about 15,000 to about 36,000 for the French.

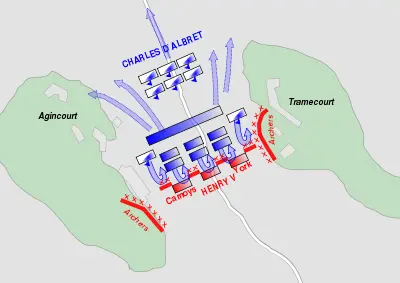

The battle was fought in the narrow strip of open land formed between the woods of Tramecourt and Agincourt. Henry deployed his army (approximately nine hundred men-at-arms and five thousand longbowmen) across a 750 yard part of the defile. It is likely that the English adopted their usual battle line of longbowmen on either flank, men-at-arms and knights in the center, and at the very center roughly two hundred archers. The English men-at-arms in plate and mail were placed shoulder to shoulder four deep. The English archers on the flanks drove pointed wooden stakes called palings into the ground at an angle to force cavalry to veer off.

The French advanced but in such large numbers that they became congested and could not use their weapons properly. At the same time the English archers rained arrows onto them. As the battle was fought on a ploughed field, and there had recently been heavy rain leaving it very muddy, it proved very tiring for the French to walk through in full plate armor. The deep, soft mud favored the English force because, once knocked to the ground, the heavily armoured French knights struggled to get back up to fight in the melee. The lightly armored English archers and soldiers were able to attack them easily.

The only French success was a sally from Agincourt Castle behind the lines. Ysambart D'Agincourt with one thousand peasants seized the King's baggage. Thinking his rear was under attack and worried that the prisoners would rearm themselves with the weapons strewn upon the field, Henry ordered their slaughter. The nobles and senior officers, wishing to ransom the captives (and perhaps from a sense of honor, having received the surrender of the prisoners), refused. The task fell to the common soldiers. It is believed more Frenchmen died in this slaughter than in the battle itself.

The French lost about six thousand against English losses of between 150-450. Among the French dead were the constable, three dukes, five counts and 90 barons and a number of notable prisoners were taken.

The Battle of Agincourt did not result in Henry conquering France, but it did allow him to escape and renew the war two years later.

- Diplomacy and command of the sea

The command of the sea was secured by driving the Genoese allies of the French out of the Channel.(His flagship, Grace Dieu – 1420) A successful diplomacy detached the emperor Sigismund from France, and by the Treaty of Canterbury paved the way to end the schism in the Church.

- 1417 campaign

So, with these two allies gone, and after two years of patient preparation since Agincourt, in 1417 the war was renewed on a larger scale. Lower Normandy was quickly conquered, Rouen cut off from Paris and besieged. The French were paralysed by the disputes of Burgundians and Armagnacs. Henry skilfully played them off one against the other, without relaxing his warlike energy. In January 1419 Rouen fell. By August the English were outside the walls of Paris. The intrigues of the French parties culminated in the assassination of John the Fearless by the Dauphin's partisans at Montereau (10 September, 1419). Philip, the new duke, and the French court threw themselves into Henry's arms. After six months' negotiation Henry was by the Treaty of Troyes recognized as heir and regent of France (see English Kings of France), and on 2 June 1420 married Catherine of Valois the king's daughter. From June to July his army besieged and took the castle at Montereau, and from that same month to November, he besieged and captured Melun, returning to England shortly thereafter.

- 1421 campaign

On 10 June, 1421, Henry sailed back to France for what would be his last military campaign. From July to August, Henry's forces besieged and captured Dreux, thus relieving allied forces at Chartres. That October, his forces lay siege to Meaux, capturing it on 2 May, 1422. Henry V died suddenly on 31 August 1422 at Bois de Vincennes near Paris, apparently from dysentery which he contracted during the siege of Meaux. He was 34 years old. Before his death, Henry V named his brother John, Duke of Bedford regent of France in the name of his son Henry VI, then only a few months old. Henry V did not live to be crowned King of France himself, as he might confidently have expected after the Treaty of Troyes, as ironically the sickly Charles VI, to whom he had been named heir, survived him by two months. Catherine took Henry's body to London and he was buried in Westminster Abbey on 7 November 1422.

Following his death, Catherine would secretly marry or have an affair with a Welsh courtier, Owen Tudor, and they would be the grandparents of King Henry VII of England.

In literature

Henry V is the subject of the eponymous play by William Shakespeare, which largely concentrates on his campaigns in France. He is also a main character in Henry IV, Part 1 and Henry IV, Part 2, where Shakespeare dramatises him as "Prince Hal," a wanton youth.

Ancestors

| Henry V of England | Father: Henry IV of England |

Paternal Grandfather: John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Edward III of England |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Philippa of Hainault | |||

| Paternal Grandmother: Blanche of Lancaster |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster | ||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Isabel de Beaumont | |||

| Mother: Mary de Bohun |

Maternal Grandfather: Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford |

Maternal Great-grandfather: William de Bohun, 1st Earl of Northampton | |

| Maternal Great-grandmother: | |||

| Maternal Grandmother: Joan FitzAlan |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Richard FitzAlan, 10th Earl of Arundel | ||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Eleanor of Lancaster |

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Christopher Allmand, Henry V (London, 1992)

- Henry V. The Practice of Kinship, edited by G.L. Harris (Oxford, 1985)

- P. Earle, The Life and times of Henry V (London, 1972)

- H.F. Hutchinson, Henry V. A Biography (London, 1967)

- Juliet Barker, Agincourt: Henry V and the Battle That Made England (London, 2005)

External links

- J. Endell Tyler. Henry of Monmouth:Memoirs of Henry the Fifth Volume 1, Volume 2 at Project Gutenberg

- Henry V Chronology

- About.com - Biography of Henry V

- Britannia: Monarchs of England - Henry V

- Columbia Encyclopedia: Henry V

- Official site of the Royal family: Henry V

- A BBC piece presenting an alternative version of Henry V

- Illustrated history of Henry V

| House of Lancaster Cadet Branch of the House of Plantagenet Born: 16 September 1387; Died: 13 August 1422 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Regnal Titles

| ||

| Preceded by: Henry IV |

King of England 1413 – 1422 |

Succeeded by: Henry VI |

| Peerage of Ireland

| ||

| Preceded by: Henry IV |

Lord of Ireland 1413 – 1422 |

Succeeded by: Henry VI |

|

| ||

| Preceded by: John of Gaunt |

Duke of Aquitaine 1399 – 1422 |

Succeeded by: Henry VI |

| Peerage of England

| ||

| Vacant Title last held by Richard II |

Prince of Wales 1399 – 1413 |

Vacant Title next held by Edward of Westminster |

| Preceded by: Henry IV |

Duke of Lancaster 1399 – 1413 |

Merged in Crown |

| Preceded by: Sir Thomas Erpynham |

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports 1409–1412 |

Succeeded by: Thomas Fitzalan |

| Notes and references | ||

| 1. Van de Pas, Leo, Genealogics.org (2007). | ||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.