Hausa people

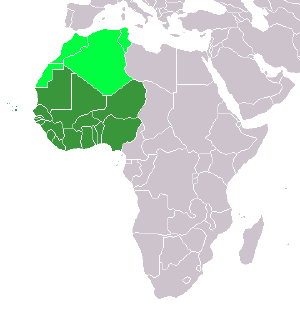

The Hausa are a Sahelian people chiefly located in the West African regions of northern Nigeria and southeastern Niger. There are also significant numbers found in northern regions of Benin, Ghana, Niger, Cameroon and in smaller communities scattered throughout West Africa and on the traditional Hajj route from West Africa, moving through Chad, and Sudan. Many Hausa have moved to large coastal cities in West Africa such as Lagos, Accra or Cotonou, as well as to countries such as Libya in search of jobs that pay cash wages. In the 12th century, the Hausa were a major African power. Seven Hausa kingdoms flourished between the Niger River and Lake Chad of which the Emirate of Kano was probably the most important. According to legend, its first king was the grandson of the founder of the Hausa states. There were 43 Hausa rulers of Kano until they lost power in 1805. Historically, these were trading kingdoms dealing in gold, cloth and leather goods. The Hausa people speak the Hausa language which belongs to the Chadic language group, a sub-group of the larger Afro-Asiatic language family and has a literary heritage dating from the 14th century. The Hausa are a major presence in Nigerian politics. The Hausa heritage is a rich cultural legacy

History and culture

Kano is considered the center of Hausa trade and culture. In terms of cultural relations to other peoples of West Africa, the Hausa are culturally and historically close to the Fulani, Songhay, Mandé and Tuareg as well as other Afro-Asiatic and Nilo-Saharan groups further East in Chad and Sudan. Islamic Shari’a law is loosely the law of the land and is understood by any full time practitioner of Islam, known as a Malam.

Between 500 C.E. and 700 C.E. Hausa people, who had been slowly moving west from Nubia and mixing in with the local Northern and Central Nigerian population, established a number of strong states in what is now Northern and Central Nigeria and Eastern Niger. With the decline of the Nok and Sokoto, who had previously controlled Central and Northern Nigeria between 800 B.C.E. and 200 C.E., the Hausa were able to emerge as the new power in the region. Closely linked with the Kanuri people of Kanem-Bornu (Lake Chad), the Hausa aristocracy adopted Islam in the 11th century CE.

By the 12th century CE the Hausa were becoming one of Africa's major powers. The architecture of the Hausa is perhaps one of the least known but most beautiful architecture of the medieval age. Many of their early mosques and palaces are bright and colourful and often include intricate graving or elaborate symbols designed into the facade. Seven Hausa states, later Emirates of Biram, Daura, Gobir, Kano, Katsina, Rano, and Zaria, really city-states loosely allied together, flourished in the 13th century situated between the River Niger and Lake Chad. They engaged in trade, selling such items and commodities as gold, leather, nuts and cloth. They survived in various forms until the late seventeenth century, when they were absorbed into the Sultanate of Sokoto before the arrival of the European powers. By the early nineteenth century, most of the Hausa emirates were under British control within what was then called the Protectorate of Nigeria. Kano was not incorporated into the British Empire until 1903, although the Hausa emir was deposed by the Fulani almost a century earlier (1895). Kano is the economic capital of Nigeria. A walled city with a Grand Mosque, it has its own Chronicle. There were 43 Hausa emirs, starting in 999 and ending in 1805 and then seven Fulani until 1903. The emirate still exists but is now only a ceremonial office. The first Emir of Kano, Bagauda, is believed to have been the grandson of Bayajidda, the founder of the Hausa dynasty (who, according to legend, was originally from Baghdad).

By 1500 C.E. the Hausa utilized a modified Arabic script known as ajami to record their own language; the Hausa compiled several written histories, the most popular being the Kano Chronicles. From the early twentieth century, literature has also been written using the Roman script, including novels and plays. [1]

In 1810 the Fulani, another Islamic African ethnic group that spanned across West Africa, invaded the Hausa states. Their cultural similarities however allowed for significant integration between the two groups, who in modern times are often demarcated as "Hausa-Fulani", rather than as individual groups and many Fulani in the region do not distinguish themselves from the Hausa.

The Hausa remain in pre-eminent in Niger and Northern Nigeria. Their impact in Nigeria is paramount, as the Hausa-Fulani amalgamation has controlled Nigerian politics for much of its independent history. They remain one of the largest and most historically grounded civilizations in West Africa. Although many Hausa have migrated to cities to find employment, many still live in small villages, where they grow food crops and raise livestock on nearby lands. Hausa farmers time their activities according to seasonal changes in rainfall and temperature.

Religion

Hausa have an ancient culture that had an extensive coverage area, and long ties to the Arabs and other Islamized peoples in West Africa, such as the Mandé, Fulani and even the Wolof of Senegambia, through extended long distance trade. Islam has been present in Hausaland since the 14th century but it was largely restricted to the region's rulers and their courts. Rural areas generally retained their animist beliefs and their urban leaders thus drew on both Islamic and African traditions to legitimize their rule. Muslim scholars of the early nineteenth century disapproved of the hybrid religion practiced in royal courts, and a desire for reform was a major motive behind the formation of the Sokoto Caliphate.[2] It was after the formation of this state that Islam became firmly entrenched in rural areas. The Hausa people have been an important vector for the spread of Islam in West Africa through economic contact, diaspora trading communities, and politics.[3]

Maguzawa, the animist religion, was practiced extensively before Islam. In the more remote areas of Hausaland Maguzawa has remained fully intact although it is much rarer in more urban areas. It often includes the sacrifice of animals for personal ends but it is thought of as illegitimate to practice Maguzawa magic for harm. What remains in more populous areas is a “cult of spirit-possession” known as Bori (religion) which still holds the old religion's elements of animism and magic. The Bori classification of reality has countless spirits, many of which are named and have specific powers. The Muslim Hausa population live in peace with the Bori. Many Bori refer to themselves as Muslims and many Muslims also utilize aspects of Bori magic to keep bad spirits out of their homes. Bori and Islam actually compliment each other in Hausa communities because the Kadiriya school of Sufi Islam, like animism which is popular among the Hausa, believes - as do all Muslims - in spirits called ‘jinn’ and some of the charms (malamai) used against them are considered compatible with Islam. The Muslim tradition of allowing for local practice that does not contradict Islam has resulted in a blend of Hausa law and Islamic Law. In addition to performing the Hajj, and praying five times a day, many Hausa also venerate Sufi saints and shrines. Other rituals related to Islam include a recent North African tradition of wearing a turban and gown, as well as the drinking of ink from slates that had scripture written on them. During Muslim festivals, like New Year and the birth of the Prophet people greet each other with gifts.

Notes

- ↑ Adamu, Yusug “Hausa Literary Movement & the 21st Century” Geography Department, Bayero University, Kano, 2002 Hausa Literary Movement and the 21st Century Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ↑ Robinson, David, Muslim Societies in African History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004 ISBN 9780521826273), p141

- ↑ Useful resources on Hausa religion at “Hausa Folk-Lore Index” , Sacred Texts Hausa Folk-Lore Index Retrieved November 13, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hill, Polly. Rural Hausa; A Village and a Setting. Cambridge [Eng.]: University Press, 1972 ISBN 9780521082426

- Koslow, Philip. Hausaland The Fortress Kingdoms. The Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1995 ISBN 9780791031308

- Parris, Ronald G. Hausa. The heritage library of African peoples. New York: Rosen Pub. Group, 1996. 9780823919833 (school level)

- Jaggar, Philip J. Hausa. London Oriental and African language library, v. 7. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins Pub. Co, 2001. ISBN 9781588110305

- Moughtin, Cliff. Hausa Architecture. London: Ethnographica, 1985 ISBN 9780905788401

- Coles, Catherine M., and Beverly B. Mack. Hausa Women in the Twentieth Century. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991 ISBN 9780299130206

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.