Great Slave Lake

| Great Slave Lake | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | |

| Lake type | remnant of a vast glacial lake |

| Primary sources | Hay River, Slave River |

| Primary outflows | Mackenzie River |

| Catchment area | 985,300 km² (380,600 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Canada |

| Max length | 480 km (298 mi) |

| Max width | 109 km (68 mi) |

| Surface area | 28,400 km² (11,000 sq mi) |

| Max depth | 614 m (2,015 ft) |

| Water volume | 2,090 km³ (501.7 cu mi, 1.694 billion acre feet) |

| Surface elevation | 156 m (512 ft) |

Great Slave Lake (French: Grand lac des Esclaves) is the second-largest lake in the Northwest Territories of Canada (behind Great Bear Lake), the deepest lake in North America, and the ninth-largest lake in the world. Its waters are extremely clear and deep at more than 2,000 feet (600 m). The lake contains many islands and supports a fishing industry and tourism.

The lake was named for the Slavey North American Indians. Originally the land was only inhabited by indigenous peoples, but fur traders established trading posts in the nineteenth century and then gold was discovered in the early twentieth century.

Today the residents of this region, with its remote northern location, small population of less than 20,000 people, and only a handful of heavy industries, cannot drink the lake's water. It has been polluted by the mining industry.

Geography

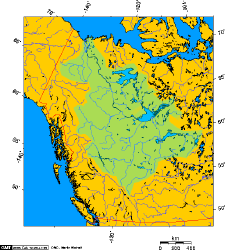

Canada's Great Plains stretch from the border with the United States to the Arctic Ocean, an area that accounts for 18 percent of Canada's land area. The plains are dominated by two river systems, the Saskatchewan (which flows west to east) and the Mackenzie, which flows past a series of lakes—Athabaska, Great Slave, and Great Bear—north to the Arctic Ocean.

The Hay and Slave Rivers are the chief tributaries of Great Slave Lake. It is drained by the Mackenzie River. Though the western shore is forested, the east shore and northern arm are tundra-like. The southern and eastern shores reach the edge of the Canadian Shield, a region of rocks that are among the oldest on earth and hence are worn down, appearing barren though it is rich in minerals. Along with other lakes such as the Great Bear and Athabasca, Great Slave is a remnant of a vast post-glacial lake.

The East Arm of Great Slave Lake is filled with islands. The Pethei Peninsula separates the East Arm into McLeod Bay in the north and Christie Bay in the south. Recreation activities abound in summer and in winter. Hiking, camping, sport and ice-fishing are all popular.

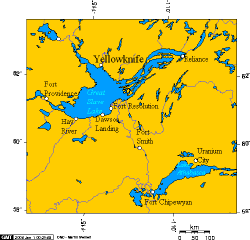

Towns around the lake include Yellowknife, Fort Providence, Hay River, and Fort Resolution. Its waters are extremely clear and deep (maximum depth more than 2,000 feet (600 meters)). The lake contains many islands and supports a fishing industry (trout and whitefish) based at the villages of Hay River and Gros Cap.

The lake is at least partially frozen during an average of eight months of the year. During winter, the ice is thick enough for semi-trailer trucks to pass over. Until 1967, when an all-season highway was built around the lake, goods were shipped across the ice to Yellowknife, located on the north shore. Goods and fuel are still shipped across frozen lakes up the winter road to the diamond mines located near the headwaters of the Coppermine River, Northwest Territories. A ferry is required to access Yellowknife during spring when the ice is not present in a solid sheet along Highway 3 where it crosses the Mackenzie River.

Wildlife

The arctic grayling is found along shorelines and in the lake's shallower bays. By consuming quantities of aquatic insects, snails, small fish, and fish eggs, it can survive for up to eight months under thick ice.

On the west side of Great Slave Lake lies the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary, containing the world’s largest wild wood bison herd, the first successful transplant of healthy wood bison into their historic range. Wood bison are taller, heavier, and longer-legged than plains bison. With a more pronounced shoulder hump and less developed beard, they roam less, feeding on grasses, sedges, willow leaves, and twigs. The sanctuary’s population of about 2,000 wood bison is just a small fraction of the almost 200,000 that once ranged throughout the region, but it is a vast increase from the wood bison’s 1891 population low of 200-250 animals that resulted from years of over-hunting during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

South of Great Slave Lake, in a remote corner of Wood Buffalo National Park, is the nesting site of a remnant flock of whooping cranes, discovered in 1954.[1]

History

Archaeologists estimate that humans settled in Canada 20,000 years ago. After the glaciers retreated (between 14,000 and 7,000 years ago), people moved north behind them. They lived in small groups, hunting and fishing. Tools, weapons, clothing, and ceremonial objects were fashioned from materials at hand. Weapons included bows and arrows, stone-tipped lances, deadfall traps, and snares. Few areas in the north were suitable for agriculture, so the conflict over land that had erupted in the United States between Native Americans and settlers were largely avoided.

British fur trader Samuel Hearne explored the area in 1771 and crossed the frozen lake while returning from a journey that had taken him from Hudson Bay to the Coppermine River and the Arctic Ocean. The next visitors are thought to be Laurent Leroux and Cuthbert Grant, founders of competing trading posts at Fort Resolution on the lake’s south shore in 1786. In 1789 Alexander Mackenzie, still in the early stages of his 1789 journey to the Arctic Ocean, reached the lake then wandered for weeks through western bays and inlets before finding the river outlet that would ultimately bear his name.

John Franklin used Fort Providence (now known as Old Fort Providence) on the lake’s north shore as a base for his 1820 expedition to the Arctic Coast.

The early settlements on the shores of Great Slave Lake were all originally Hudson Bay Company posts. The fur trade continued to dominate the economy until gold was discovered in the 1930s. The small town of Yellowknife quickly sprouted and developed into the territory's capital.

In 1967, an all-season highway was built around the lake, originally an extension of the Mackenzie Highway but now known as Highway 3.

On January 24, 1978, a Soviet Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellite, named Cosmos 954, built with an onboard nuclear reactor fell from orbit and landed in the lake. With all the ice and snow on the lake the satellite exploded on impact, causing its nuclear fuel to fall over the area. The nuclear fuel was picked up by a group called Operation Morning Light, formed with both American and Canadian members.[2]

Environment

Great Slave Lake is perceived as one of the most pristine water bodies in the world, yet residents of Yellowknife, on its northern shore, cannot drink the lake's water and must draw their water from the Yellowknife River, five kilometers away.

Beginning in 1943, the “roasting” process that was used to remove gold from arsenopyrite rock sent arsenic trioxide and sulfur dioxide into the air. Pollution control devices installed during the 1950s trapped arsenic dust, but contamination was still detected during the 1970s. Though roasting was discontinued in 1999, some 238,000 tons of highly toxic, water soluble arsenic trioxide dust were stored in 15 underground chambers a few hundred meters from Great Slave Lake. The storage vaults are contained in bedrock and sealed with concrete bulkheads, but concerns remain about leaching of arsenic into groundwater. A joint long-term management strategy for the underground arsenic vaults is being formulated by the Canadian federal government and the current owner of the mine; their options include freezing the arsenic in place, extracting it, and treating it as hazardous waste.

Zinc and lead are also mined in the area.

Notes

- ↑ Paul A. Johnsgard, Whooper Recount: A close look at these endangered cranes reveals that, while their numbers are increasing, their rate of increase is actually declining University of Nebraska, February 1982. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Steve Weintz, Operation Morning Light: The Nuclear Satellite That Almost Decimated America The National Interest, November 23, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Craig (ed.) The Illustrated History of Canada. Toronto, Canada: Key Porter Books, 2002. ISBN 1552635082

- Bothwell, Robert. A Traveller's History of Canada. Windrush Pr, 2001. ISBN 1900624486

- Department of Fisheries: Canada. Sailing directions, Great Slave Lake and Mackenzie River. Ottawa: Dept. of Fisheries and Oceans, 1981. ISBN 0660110229

- Gibson, J.J., T.D. Prowse, and D.L. Peters. Partitioning impacts of climate and regulation on water level variability in Great Slave Lake. Journal of Hydrology, 329(1) (2006): 196.

- Hicks, F., X. Chen, and D. Andres. Effects of ice on the hydraulics of Mackenzie River at the outlet of Great Slave Lake, N.W.T.: A case study. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering. Revue Canadienne De G̐ưenie Civil. 22(1) (1995):43.

- Kasten, H. The captain's course secrets of Great Slave Lake. Edmonton: H. Kasten, 2004. ISBN 097366410X

- Jenness, R. Great Slave Lake fishing industry. Ottawa: Northern Co-ordination and Research Centre. Dept. of Northern Affairs and National Resources, 1963.

- Keleher, J.J. Supplementary information regarding exploitation of Great Slave Lake salmonid community. Winnipeg: Fisheries Research Board, Freshwater Institute, 1972.

- Mason, J.A. Notes on the Indians of the Great Slave Lake area. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1946.

- Sirois, J., M.A. Fournier, and M.F. Kay. The colonial waterbirds of Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories an annotated atlas. Ottawa: Canadian Wildlife Service, 1995.

External Links

All links retrieved January 21, 2020.

- Great Slave Lake Encyclopaedia Britannica online

- Great Slave Lake The Canadian Encylopedia

- View from space: North America’s deepest lake

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.