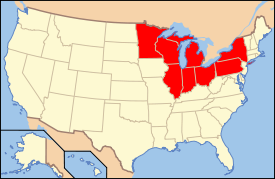

Great Lakes region (North America)

The Great Lakes region includes much of the Canadian province of Ontario and portions of eight U.S. states that border the Great Lakes: New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The region is home to 60 million people. Buffalo, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Toronto are among the major cities located along the Great Lakes, contributing to the region's $2 trillion economy—an amount that exceeds any nation other than Japan and the United States.

Spanning more than 750 miles (1,200 km) from west to east, these vast inland freshwater seas have provided water for consumption, transportation, power, recreation, and a host of other uses. The Great Lakes are the largest system of fresh, surface water on earth, containing roughly 18 percent of the world supply. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, only the polar ice caps contain more fresh water.

The water of the lakes and the many resources of the Great Lakes basin have played a major role in the history and development of the United States and Canada. For the early European explorers and settlers, the lakes and their tributaries were the avenues for penetrating the continent, extracting valued resources, and carrying local products abroad.

Now the Great Lakes basin is home to more than one-tenth of the population of the United States and one-quarter of the population of Canada. Some of the world's largest concentrations of industrial capacity are located in the Great Lakes region. Nearly 25 percent of the total Canadian agricultural production and seven percent of the American production are located in the basin. The United States considers the Great Lakes a fourth seacoast.

The Great Lakes region has made significant contributions in natural resources, political economy, technology, and culture. Among the most prominent are democratic government and economy; inventions and industrial production for agricultural machinery, automobile manufacture, commercial architecture, and transportation.

Geography

The Great Lakes hold almost one-fifth of the world's surface fresh water. The region has large mineral deposits of iron ore, especially in the Minnesota and Michigan Upper Peninsula Mesabi Range; and anthracite coal from western Pennsylvania through southern Illinois. The abundance of iron and coal furnished the basic materials for the world's largest steel production in the last half of the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth. In addition, western Pennsylvania hosted the world's first major oil boom.

The region's soil is rich and still produces large amounts of cereals and corn. Wisconsin cranberry bogs and Minnesotan wild rice still yield natural foods to which Native Americans introduced Europeans in the seventeenth century.

Cities

Major U.S. cities in the region are Buffalo, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Cleveland and Columbus, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Indianapolis, Indiana; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The major Canadian cities are Toronto, Hamilton, Sarnia, Thunder Bay, and Windsor, Ontario.

Climate

The weather in the Great Lakes basin is affected by three factors: air masses from other regions, the location of the basin within a large continental landmass, and the moderating influence of the lakes themselves. The prevailing movement of air is from the west. The characteristically changeable weather of the region is the result of alternating flows of warm, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico and cold, dry air from the Arctic.

In summer, the northern region around Lake Superior generally receives cool, dry air masses from the Canadian northwest. In the south, tropical air masses originating in the Gulf of Mexico are most influential. As the Gulf air crosses the lakes, the bottom layers remain cool while the top layers are warmed. Occasionally, the upper layer traps the cooler air below, which in turn traps moisture and airborne pollutants, and prevents them from rising and dispersing. This is called a temperature inversion and can result in dank, humid days in areas in the midst of the basin, such as Michigan and southern Ontario, and can also cause smog in low-lying industrial areas.

Increased summer sunshine warms the surface layer of water in the lakes, making it lighter than the colder water below. In the fall and winter months, release of the heat stored in the lakes moderates the climate near the shores of the lakes. Parts of southern Ontario, Michigan, and western New York enjoy milder winters than similar mid-continental areas at lower latitudes.

In the autumn, the rapid movement and occasional clash of warm and cold air masses through the region produce strong winds. Air temperatures begin to drop gradually and less sunlight, combined with increased cloudiness, signal more storms and precipitation. Late autumn storms are often the most perilous for navigation and shipping on the lakes.

In winter, the Great Lakes region is affected by two major air masses. Arctic air from the northwest is very cold and dry when it enters the basin, but is warmed and picks up moisture traveling over the comparatively warmer lakes. When it reaches the land, the moisture condenses as snow, creating heavy snowfalls on the lee side of the lakes. Ice frequently covers Lake Erie but seldom fully covers the other lakes.

Spring in the Great Lakes region, like autumn, is characterized by variable weather. Alternating air masses move through rapidly, resulting in frequent cloud cover and thunderstorms. By early spring, the warmer air and increased sunshine begin to melt the snow and lake ice, starting again the thermal layering of the lakes. The lakes are slower to warm than the land and tend to keep adjacent land areas cool, thus prolonging cool conditions sometimes well into April. Most years, this delays the leafing and blossoming of plants, protecting tender plants, such as fruit trees, from late frosts.

Climate change

Climatologists have used models to determine the manner in which an increase of carbon dioxide emissions will affect the climate in the Great Lakes basin. Several of these models exist, and they show that at twice the carbon dioxide level, the climate of the basin will be warmer by 2-4°C and slightly damper than at present. For example, Toronto's climate would resemble the present climate of southern Ohio.

Warmer climates would mean increased evaporation from the lake surfaces and evapotranspiration from the land surface. This in turn would augment the percentage of precipitation that is returned to the atmosphere. Studies have shown that the amount of water contributed by each lake basin to the overall hydrologic system would decrease by 23 to 50 percent. The resulting decreases in average lake levels would be from half a meter to two meters, depending on the model used for the study.[1]

Large declines in lake levels would create large-scale economic concern for the commercial users of the water system. Shipping companies and hydroelectric power companies would suffer economic repercussions, and harbors and marinas would be adversely affected. While the precision of such projections remains uncertain, the possibility of their accuracy suggests important long-term implications for the Great Lakes.

Ecology

More than 160 non-indigenous species (also commonly referred to as nuisance, non-native, exotic, invasive, and alien species) have been introduced into the Great Lakes basin since the 1800s, especially since the expansion of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959, which allowed greater transoceanic shipping traffic. Such species threaten the diversity or abundance of native species and the ecological stability of infested waters, may threaten public health, and can have widespread economic impacts. The zebra mussel, for example, colonizes the intake/discharge pipes of hundreds of facilities that use raw water from the Great Lakes, incurring extensive monitoring and control costs. So far, an effective control for most of these species has not been found.

History

Prior to European settlement, Iroquoian peoples lived around Lakes Erie and Ontario, Algonquin peoples around most of the rest, with the exception of the Siouan Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) in Wisconsin.

Great Lakes states on the United States side derived from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. The ordinance, adopted in its final form just before the writing of the United States Constitution, was a sweeping, visionary proposal to create what was at the time a radical experiment in democratic governance and economy. The Iroquois Confederacy and its covenant of the Great Peace served as forerunner and model for both the U.S. Constitution and the ordinance.

The Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery, restricted primogeniture, mandated universal public education, provided for affordable farm land to people who settled and improved it, and required peaceful, lawful treatment of indigenous Indian populations. The ordinance also prohibited the establishment of state religion and established civic rights that foreshadowed the United States Bill of Rights. Civil rights included freedom from cruel and unusual punishment, trial by jury, and exemption from unreasonable search and seizure. States were authorized to organize constitutional conventions and petition for admission as states equal to the original thirteen.

Not all provisions were promptly or fully adopted, but the basic constitutional framework effectively prescribed a free, self-reliant institutional framework and culture. Five states evolved from its provisions: Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin. The northeastern section of Minnesota, from the Mississippi to St. Croix River, also fell under ordinance jurisdiction and extended the constitution and culture of the Old Northwest to the Dakotas.

The Northwest Ordinance also made mention of Native Americans: "The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed."[2]

Many American Indians in Ohio refused to recognize the validity of treaties signed after the Revolutionary War that ceded lands north of the Ohio River to the United States. In a conflict sometimes known as the Northwest Indian War, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Little Turtle of the Miamis formed a confederation to stop white settlement. After the Indian confederation had killed more than eight hundred soldiers in two devastating battles—the worst defeats ever suffered by the U.S. at the hands of Native Americans—President Washington assigned General Anthony Wayne command of a new army, which eventually defeated the confederation and thus allowed whites to continue settling the territory.

The British-Canadian London Conference of 1866, and subsequent Constitution Act of 1867 analogously derived from political, and some military, turmoil in the former jurisdiction of Upper Canada, which was renamed and organized in the new dominion as the Province of Ontario. Like the provisions of the ordinance, Ontario prohibited slavery, made provisions for land distribution to farmers who owned their own land, and mandated universal public education.

Regional cooperation

In 2003, the governors of the U.S. Great Lakes states adopted nine priorities that embody the goals of protecting and restoring the natural habitat and water quality of the Great Lakes Basin. In 2005, they reached agreement on the Great Lakes Compact, providing a comprehensive management framework for achieving sustainable water use and resource protection, and got the premiers of the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec to agree as well. Since 2005, each of the state legislatures involved has ratified the Compact. At the federal level, a resolution of consent to the Compact was approved by the U.S. Senate in August 2008, and by the U.S. House of Representatives a month later. On October 3, 2008, President George W. Bush signed the joint resolution of Congress providing consent to the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact.

The commitments outlined in the Compact include developing water conservation programs, compatible water use reporting systems, and science-based approaches for state management of water withdrawals across the Great Lakes Basin.[3]

In 2006, the Brookings Institution reported that a regional investment of $25 billion to implement the strategy would result in short- and long-term returns of $80-100 billion, including:

- $6.5-11.8 billion in direct benefits from tourism, fishing, and recreation

- $50-125 million in reduced costs to municipalities, and

- $12-19 billion in increased coastal property values.[3]

In January 2009, the state of Michigan said it planned to ask the Obama administration for more than $3 billion in funding for Great Lakes cleanup, management, and development.

Government and social institutions

Historically, governance in the region was grounded in social institutions that were fundamentally more powerful, popular, and determinative than the governments in the region, which remained comparatively small, weak, and distrusted until World War II.

The most powerful and influential of these were religious denominations and congregations. Even the most centralized denominations—the Roman Catholic Church, the Episcopal Church, and Lutheran synods—necessarily became congregational in polity and to a lesser extent doctrine. There was no alternative, because without state funding, congregations were forced to depend on the voluntary donations, activities, and tithes of their members. In most settlements, congregations formed the social infrastructure that supported parish and common township schools, local boards and commissions, and an increasingly vital social life.

Congregations and township politics gave rise to voluntary organizations. Three kinds of these were especially significant to the region's development: agricultural associations, voluntary self-help associations, and political parties. The agricultural associations gave rise to the nineteenth-century Grange, which in turn generated the agricultural cooperatives that defined much of the rural political economy and culture throughout the region. Fraternal, ethnic, and civic organizations extended cooperatives and supported local ventures, from insurance companies to orphanages and hospitals.

The region's greatest institutional contributions were industrial labor organization and state educational systems. The Big Ten Conference memorializes the nation's first region in which every state sponsored major research, technical-agricultural, and teacher-training colleges and universities. The Congress of Industrial Organizations grew out of the region's coal and iron mines; steel, automobile, and rubber industries; and breakthrough strikes and contracts of Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan.

Technology

The Great Lakes region hosted a number of breakthroughs in agricultural technology. The mechanical reaper invented by Cyrus McCormick, John Deere's steel plow, and the grain elevator are some of its most memorable contributions.

Case Western Reserve University and the University of Chicago figured prominently in developing nuclear power. Automobile manufacture developed simultaneously in Ohio and Indiana and became centered in the Detroit area of Michigan. Henry Ford's movable assembly line drew on regional experience in meat processing, agricultural machinery manufacture, and the industrial engineering of steel in revolutionizing the modern era of mass-production manufacturing.

Architecture

Perhaps no field proved so influential as architecture, and no city more significant than Chicago. William LeBaron Jenney was the architect of the first skyscraper in the world. The Home Insurance Building in Chicago is the first skyscraper because of its use of structural steel. Chicago to this day holds some of the world's greatest architecture. Less famous, but equally influential, was the 1832 invention of balloon-framing in Chicago that replaced heavy timber construction requiring massive beams and great woodworking skill with pre-cut timber. This new lumber could be nailed together by farmers and settlers who used it to build homes and barns throughout the western prairies and plains.

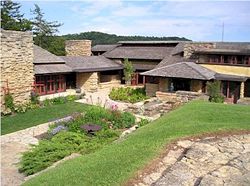

Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most prominent and influential architects of the twentieth century, hailed from the town of Richland Center, Wisconsin. His childhood in the Great Lakes region engendered within him a deep and almost mystical love of nature. His designs reflected the observation of the beauty of natural things. Wright's enduring legacy is a highly innovative, architectural style that strictly departed from European influences to create a purely American form, one that actively promoted the idea that buildings can exist in harmony with the natural environment.

Transportation

Contributions to modern transportation include the Wright brothers' early airplanes, distinctive Great Lakes freighters, and railroad beds constructed of wooden ties and steel rails. The early nineteenth century Erie Canal and mid-twentieth century Saint Lawrence Seaway expanded the scale and engineering for massive water-borne freight.

Economy

The Great Lakes region has been a major center for industry since the Industrial Revolution. Many large American and Canadian companies are headquartered in the region. According to the Brookings Institution, if it were a country, the region's economy would be the second-largest economic unit on earth (with a $4.2-trillion gross regional product), second only to the United States' economy as a whole.

Looking to the future

Although the ecosystem has shown signs of recovery, pollution will continue to be a major concern in the years to come. A broader scope of regulation of toxic chemicals may be necessary as research and monitoring reveal practices that are harmful. More stringent controls of waste disposal are already being applied in many locations. Agricultural practices are being examined because of the far-reaching effects of pesticides and fertilizers. In addition to pollution problems, better understanding of the living resources and habitats of the Great Lakes basin is needed to support protection and rehabilitation of the biodiversity of the ecosystem and to strengthen management of natural resources. Wetlands, forests, shorelines and other environmentally sensitive areas will have to be more strictly protected and, in some cases, rehabilitated and expanded.

As health protection measures are taken and environmental cleanup continues, rehabilitation of degraded areas and prevention of further damage are being recognized as the best way to promote good health, and protect and preserve the living resources and habitats of the Great Lakes.[4]

The need for enhanced funding to finance cleanup of contaminated sediments in the Great Lakes and ecosystems restoration was documented by the Great Lakes Regional Collaboration in its December 2005 report. That report estimated the need for federal Legacy funds to be $2.25 billion total (or $150 million annually between 2006 and 2020).[5]

Notes

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Climate Change And The Great Lakes Retrieved January 27, 2009

- ↑ Archiving Early America, The Northwest Ordinance Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (January 2009), MI Great Lakes Plan - Our Path to Protect, Restore, and Sustain Michigan’s Natural Treasures Retrieved January 27, 2009

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, People in the Ecosystem Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ Northeast Midwest Institute (December 2006), Opportunities for Financing Great Lakes Cleanup and Ecosystem Restoration Retrieved January 27, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Great Lakes Information Network. Great Lakes Information Network Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- McLaughlin, Robert. 1967. The heartland: Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin. New York: Time inc. OCLC 958883

- Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. Great Lakes Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- Tanner, Helen Hornbeck, and Miklos Pinther. 1987. Atlas of Great Lakes Indian history. The Civilization of the American Indian series, v. 174. Norman: Published for the Newberry Library by the University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806115153

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book Retrieved January 29, 2009.

External links

All links retrieved July 13, 2017.

- Midwest Lakes Policy Center

- The Nature Conservancy's Great Lakes Program

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.