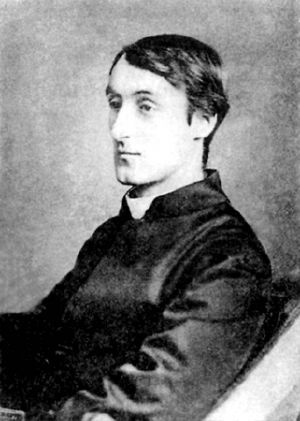

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Gerard Manley Hopkins (July 28, 1844 - June 8, 1889) was a British Victorian poet and Jesuit priest.

Life

Hopkins was born in Stratford, Essex. He was the eldest of nine children, the son of Catherine and Manley Hopkins, an insurance agent and consul-general for Hawaii based in London. He was educated at Highgate grammar school and then Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied classics. It was at Oxford that he forged the friendship with Robert Bridges which would be of importance in his development as a poet, and posthumous acclaim. He began his time at Oxford as a keen socialiser and prolific poet but he seems to have alarmed himself with this change in his behaviour and became more studious and recorded his sins in his diary. He became a follower of Edward Pusey and a member of the Oxford Movement and in 1866, following the example of John Henry Newman, he converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. After his graduation in 1867 Newman found him a teaching post but the following year he decided to enter the priesthood, pausing only to visit Switzerland.

Influenced by his father who also wrote poetry, Hopkins wrote poetry while young, winning a prize for his poetry while at grammar school. His decision to become a Jesuit led him to burn much of his early poetry as he felt it incompatible with his vocation. Writing would remain something of a concern for him as he felt that his interest in poetry prevented him from wholly devoting himself to his religion. He continued to write a detailed journal until 1874. Unable to suppress his desire to describe the natural world, he also continued to write occasional poems. He would later write sermons and other religious pieces. In 1875 he was moved, once more, to write a lengthy poem, The Wreck of the Deutschland. This work was inspired by the Deutschland, a naval disaster in which 157 people died including five Franciscan nuns who had been leaving Germany due to harsh anti-Catholic laws. The work displays both the religious concerns and some of the unusual meter and rhythms of his subsequent poetry not present in his few remaining early works. It not only depicts the dramatic events and heroic deeds but also tells of the poet's reconciling the terrible events with God's higher purpose. The poem was accepted but not printed by a Jesuit publication and this rejection fuelled his ambivalence about his poetry.

Hopkins chose the austere and restrictive life of a Jesuit and was at times gloomy. The brilliant student who had left Oxford with a first class honours degree failed his final theology exam. This failure meant that, although ordained in 1877 Hopkins, would not likely progress in the order. Whilst not always happy in his studies there was at least stability, the uncertain and varied work after ordination was even less to his liking. He served in various parishes in England and Scotland and taught at Mount St Mary's College, Sheffield, and Stonyhurst College, Lancashire. In 1884 he became professor of Greek literature at University College Dublin. His Englishness and his disagreement with the Irish politics of the time, as well as his own small stature (5'2"), unprepossessing nature and own personal oddities meant that he was not a particularly effective teacher. This as well as his isolation in Ireland deepened his gloom and his poems of the time, such as I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark, reflected this; called by Hopkins "terrible sonnets".

After suffering ill health for several years and bouts of diarrhoea, Hopkins died of typhoid fever in 1889 and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin.

Poetry

Much of Hopkins' historical importance has to do with the changes he brought to the form of poetry, which ran contrary to conventional ideas of meter. Prior to Hopkins, most Middle English and Modern English poetry was based on a rhythmic structure inherited from the Norman side of English's literary heritage. This structure is based on repeating groups of two or three syllables, with the stressed syllable falling in the same place on each repetition. Hopkins called this structure running rhythm, and though he wrote some of his early verse in running rhythm he became fascinated with the older rhythmic structure of the Anglo-Saxon tradition, of which Beowulf is the most famous example. Hopkins called this rhythmic structure sprung rhythm. Sprung rhythm is structured around feet with a variable number of syllables, generally between one and four syllables per foot, with the stress always falling on the first syllable in a foot. In reality, it more closely resembles the "rolling stresses" of Robinson Jeffers, another poet who disavowed conventional meter. Hopkins saw sprung rhythm as a way to escape the constraints of running rhythm, which he said inevitably, pushed poetry written in it to become "same and tame." In this way, Hopkins can be seen as anticipating much of free verse. His work has no great affinity with either of the contemporary Pre-Raphaelite and neo-romanticism schools, although he does share their descriptive love of nature and he is often seen as a precursor to modernist poetry or as a bridge between the two poetic eras.

Another influence on him was the Welsh language he learnt while studying theology at St. Beuno's College in Wales. The poetic forms of Welsh literature and particularly cynghanedd with its emphasis on repeating sounds accorded with his own style and became a prominent feature of his work. This reliance on similar sounding words with close or differing senses mean that his poems are best understood if read aloud. An important element in his work is Hopkins' own concept of "inscape" which was derived, in part, from the medieval theologian Duns Scotus. The exact detail of "inscape" is uncertain and probably known to Hopkins alone but it has to do with the individual essence and uniqueness of every physical thing. This is communicated from an object by its "instress" and ensures the transmission of the item's importance in the wider creation. His poems would then try to present this "inscape" so that a poem like "The Windhover" aims to depict not the bird in general but instead one instance and its relation to the breeze. This is just one interpretation to probably Hopkins' most studied poem and one which he called his best.[1]

During his lifetime, Hopkins published few poems. It was only through the efforts of Robert Bridges that his works were seen. Despite Hopkins burning all his poems on entering the priesthood, he had already sent some to Bridges who, with a few other friends, was the only person to see many of them for some years. After Hopkins' death they were distributed to a wider audience, mostly fellow poets, and in 1918 Bridges, by then poet laureate, published a collected edition.

Bibliography of Poems

- The Wreck of the Deutschland

- God's Grandeur

- As Kingfishers Catch Fire

- Pied Beauty (a curtal sonnet)

- Carrion Comfort

- The Windhover: To Christ our Lord

- Spring and Fall, To a Young Child

- The Habit of Perfection

- The Sea and the Skylark

- Inversnaid

Audio

- Catholic singer-songwriter Sean O'Leary (b.1953) has produced a collection of contemporary settings of Hopkins' poems titled The Alchemist: Gerard Manley Hopkins Poems In Musical Adaptations [48 page booklet with accompanying double album - 2CD - 120 minutes], ISBN 0-9550649-0-2, 2005. The 22 poems include: The Wreck Of The Deutschland, God's Grandeur, Spring, The Windhover, Felix Randal, and the 'Terrible Sonnets'.

- Richard Austin reads Hopkins' poetry in BACK TO BEAUTY'S GIVER [Audio book- CD], ISBN 0-9548188-0-6, 2003. 27 poems, including: The Wreck Of The Deutschland, God's Grandeur, The Windhover, Pied Beauty and Binsley Poplars, and the 'Terrible Sonnets'.

External links

- Gerard Manley Hopkins Society

- Gerard Manley Hopkins Poems In Musical Adaptations

- The Hopkins Quarterly

- Online texts of Hopkins Poems: First Edition (1918)

- Web Concordance of Hopkins Poems

- Readings of Hopkins' Poetry

- The Victorian Web - Gerard Manley Hopkins - An Overview

- That Nature Is A Heraclitean Fire - Excerpt - Musical adaptation by Sean O'Leary (MP3)

- The Wreck Of The Deutschland - Verse 1 - Musical adaptation by Sean O'Leary (MP3)

- 8 Song Samples from Musical Adaptations of Hopkins' Poetry

- LibriVox - Free Audio Recording of As Kingfishers Catch Fire.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.