Difference between revisions of "Elf" - New World Encyclopedia

Nick Perez (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (39 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Mythical creatures]] | ||

| + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} | ||

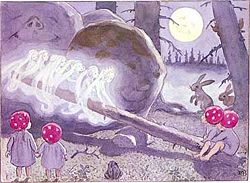

| + | [[Image:Tomtebobarnen.jpg|thumb|250px|right|Little ''älvor'' (elves), playing with ''Tomtebobarnen'' (children of the forest). From ''Children of the Forest'' (1910) by Swedish author and illustrator Elsa Beskow.]] | ||

| + | An '''elf''' is a [[mystical creature]] found in [[Norse mythology]] that still survives in northern [[Europe]]an [[folklore]]. Following their role in [[J.R.R. Tolkien]]'s epic work ''The Lord of the Rings'', elves have become staple characters of modern [[fantasy]] tales. There is great diversity in how elves have been portrayed; depending on the [[culture]], elves can be depicted as youthful-seeming men and women of great [[beauty]] living in [[forest]]s and other natural places, or small trickster creatures. | ||

| − | + | In early [[folklore]], elves were generally possessed of supernatural abilities, often related to [[disease]], which they could use for good (healing) or ill (sickening) depending on their relationship toward the person they were affecting. They also had some power over time, in that they could entrap [[human being]]s with their [[music]] and [[dance]]. Some elves were small, [[fairy]]-like creatures, possibly invisible, whereas others appeared human-sized. Generally they were long-lived, if not [[immortality|immortal]]. While many of these depictions are considered purely fictional, creatures such as elves, somewhat like human beings but with abilities that transcend the physical realm, find correlates in the [[angel]]s and [[demon]]s of many [[religion]]s. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| − | Some [[linguistics|linguists]] believe that ''elf'' | + | Some [[linguistics|linguists]] believe that ''elf,'' ''álf,'' and related words derive from the Proto-Indo-European root ''albh'' meaning "white," but the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' lists the earliest rendition of the name as originating from Old High German, before being transmitted into Middle High German, West Saxon, and then finally arriving in [[English language|English]] in its current form.<ref>''Oxford English Dictionary'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), s.v. “Elf.” </ref> Though the exact [[etymology]] may be a contention among linguists, it is clear that nearly every [[culture]] in [[Europe|European]] history has had its own name for the similar representation of the creatures commonly called elves. "Elf" can be pluralized both as "elves" and "elfs." Something associated with elves or the qualities of elves is described by the adjectives "elven," "elvish," "elfin," or "elfish." |

==Cultural Variations== | ==Cultural Variations== | ||

| Line 14: | Line 16: | ||

===Norse=== | ===Norse=== | ||

| − | The earliest preserved description of elves comes from Norse mythology. In [[Old Norse language|Old Norse]] they are called '' | + | {{readout|The earliest preserved description of elves comes from [[Norse mythology]]|right}}. In [[Old Norse language|Old Norse]] they are called ''álfr,'' plural ''álfar.'' Although the concept itself is not entirely clear in surviving texts and records, elves appear to have been understood as powerful and beautiful [[human]]-sized beings. They are commonly referred to collectively as semi-divine beings associated with [[fertility]] as well as the cult of the ancestors. As such, elves appear similar to the [[Animism|animistic]] belief in [[Spiritual being|spirits]] of nature and of the deceased, common to nearly all human [[religion]]s; something that is true also for the Old Norse belief in ''fylgjur'' and ''vörðar'' ("follower" and "warden" spirits, respectively). |

| − | [[Image:Freyr_art.jpg|thumb|left|180px|The god [[Freyr]], the lord of the light-elves]] | + | [[Image:Freyr_art.jpg|thumb|left|180px|The god [[Freyr]], the lord of the light-elves]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | The earliest references come from [[ | + | The earliest references come from Skaldic [[poetry]], the ''Poetic Edda,'' and [[legend]]ary sagas. Here elves are linked with the [[Æsir]] (or Aesir), particularly through the common phrase "Æsir and the elves," which presumably means "all the gods." The elves have also been compared or identified with the [[Vanir]] (fertility gods) by some scholars.<ref name=hall>Alaric Timothy Peter Hall, [http://www.alarichall.org.uk/ahphdprol.pdf "The Meanings of ''Elf'' and Elves in Medieval England"] (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Glasgow, 2004). Retrieved August 27, 2008. </ref> However, in the ''Alvíssmál'' ("The Sayings of All-Wise"), the elves are considered distinct from both the Vanir and the Æsir, as revealed by a series of comparative names in which Æsir, Vanir, and elves are given their own versions for various words in a reflection of their individual racial preferences. Possibly, the words designate a difference in status between the major fertility gods (the Vanir) and the minor ones (the elves). ''Grímnismál'' relates that the Van [[Freyr]] was the lord of ''Álfheimr'' (meaning "elf-world"), the home of the light-elves. ''Lokasenna'' relates that a large group of Æsir and elves had assembled at Ægir's court for a banquet. Several minor forces, the servants of gods, are presented such as Byggvir and Beyla, who belonged to [[Freyr]], the lord of the elves, and they were probably elves, since they were not counted among the gods. Two other mentioned servants were Fimafeng (who was murdered by [[Loki]]) and Eldir. |

| − | + | ||

| − | Some speculate that Vanir and elves belong to an earlier [[ | + | Some speculate that Vanir and elves belong to an earlier Nordic [[Bronze Age]] religion of [[Scandinavia]], and were later replaced by the Æsir as main gods. Others (most notably Georges Dumézil) have argued that the Vanir were the gods of the common Norsemen, and the Æsir those of the priest and warrior [[caste]]s. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Scandinavian elves=== |

| − | + | In [[Scandinavia]]n [[folklore]], which is a later blend of [[Norse mythology]] and elements of [[Christianity|Christian]] [[mythology]], an ''elf'' is called ''elver'' in [[Danish language|Danish]], ''alv'' in [[Norwegian language|Norwegian]], and ''alv'' or ''älva'' in [[Swedish language|Swedish]] (the first form being masculine, the second feminine). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | In [[Denmark]] and [[Sweden]], the elves appear as beings distinct from the ''vetter,'' even though the border between them is diffuse. The ''alf'' found in the fairy tale ''The Elf of the Rose'' by Danish author [[Hans Christian Andersen]] is so tiny that he can have a [[rose]] blossom for his home, and has "wings that reached from his shoulders to his feet." Yet, Andersen also wrote about ''elvere'' in ''The Elfin Hill,'' which were more like those of traditional Danish folklore, who were beautiful females, living in hills and boulders, capable of dancing a man to death. Like the ''huldra'' in Norway and Sweden, they are hollow when seen from the back. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The elves are typically pictured as fair-haired, white-clad, and, like most creatures in Scandinavian folklore, can be extremely dangerous when offended. In the stories, they often play the role of [[disease]]-spirits. The most common, though also most harmless case, was various irritating skin rashes, which were called ''älvablåst'' (elven blow) and could be cured by a forceful counter-blow (a handy pair of bellows was most useful for this purpose). ''Skålgropar,'' a particular kind of petroglyph found in Scandinavia, were known in older times as ''älvkvarnar'' (elven mills), pointing to their believed usage. One could appease the elves by offering them a treat (preferably [[butter]]) placed into an elven mill—perhaps a custom with roots in the Old Norse ''álfablót.'' | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The elves could be seen dancing over meadows, particularly at night and on misty mornings. They left a kind of circle where they had danced, which were called ''älvdanser'' (elf dances) or ''älvringar'' (elf circles), and to urinate in one was thought to cause [[venereal disease]]. Typically, the circles consisted of a ring of small [[mushroom]]s, but there was also another kind of elf circle: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>On lake shores, where the forest met the lake, you could find elf circles. They were round places where the grass had been flattened like a floor. Elves had danced there. By Lake Tisaren, I have seen one of those. It could be dangerous and one could become ill if one had trodden over such a place or if one destroyed anything there.<ref>An account given in 1926, found in Anne Marie Hellström, ''En Krönika om Åsbro.'' (Sweden: 1990, ISBN 9171947264), 36.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | If a [[human being]] watched the dance of the elves, he would discover that even though only a few hours seemed to have passed, many years had passed in the real world, a remote parallel to the [[Ireland|Irish]] ''sídhe.'' In a song from the late [[Middle Ages]] about Olaf Liljekrans, the elven queen invites him to dance. He refuses, knowing what will happen if he joins the dance and he is also on his way home to his own wedding. The queen offers him gifts, but he declines. She threatens to kill him if he does not join, but he rides off and dies of the disease she sent upon him, and his young bride dies of a broken heart.<ref>Thomas Keightley. 1870. [http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/ The Fairy Mythology]. provides two translated versions of the song: Thomas Keightley, [http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm018.htm “Sir Olof in Elve-Dance”'] and [http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm019.htm “The Elf-Woman and Sir Olof,”] in [http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/ ''The Fairy Mythology''] (London, H.G. Bohn, 1870). ''sacredtexts.com''. Retrieved June 11, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | However, the elves were not exclusively young and beautiful. In the Swedish folktale ''Little Rosa and Long Leda,'' an elvish woman ''(älvakvinna)'' arrives in the end and saves the heroine, Little Rose, on condition that the king's [[cattle]] no longer graze on her hill. She is described as an old woman and by her aspect people saw that she belonged to the ''subterraneans.''<ref>“Lilla Rosa och Långa Leda,” ''Svenska folksagor'' (Stockholm, Almquist & Wiksell Förlag AB, 1984), 158.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | '' | ||

| − | |||

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===German elves=== | |

| − | + | ||

| + | What remained of the belief in elves in [[Germany|German]] [[folklore]] was the idea that they were mischievous pranksters that could cause [[disease]] to [[cattle]] and people, and bring bad [[dream]]s to sleepers. The German word for "nightmare," ''Albtraum,'' means "elf dream." The archaic form ''Albdruck'' means "elf pressure." It was believed that nightmares were a result of an elf sitting on the dreamer's head. This aspect of German elf-belief largely corresponds to the [[Scandinavia]]n belief in the ''mara.'' It is also similar to the [[legend]]s regarding incubi and succubi [[demon]]s.<ref name=hall/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The legend of ''Der Erlkönig'' appears to have originated in fairly recent times in [[Denmark]]. The ''Erlkönig'''s nature has been the subject of some debate. The name translates literally from the German as "Alder King" rather than its common English translation, "Elf King" (which would be rendered as ''Elfenkönig'' in German). It has often been suggested that ''Erlkönig'' is a mistranslation from the original Danish ''elverkonge'' or ''elverkonge,'' which does mean "elf king." | ||

| − | + | According to German and Danish folklore, the ''Erlkönig'' appears as an omen of death, much like the [[banshee]] in [[Ireland|Irish]] [[mythology]]. Unlike the banshee, however, the ''Erlkönig'' will appear only to the person about to die. His form and expression also tells the person what sort of death they will have: a pained expression means a painful death, a peaceful expression means a peaceful death. This aspect of the legend was immortalized by [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe]] in his poem ''Der Erlkönig,'' based on "Erlkönigs Tochter" ("Erlkönig's Daughter"), a Danish work translated into German by [[Johann Gottfried Herder]]. The poem was later set to music by [[Franz Schubert]]. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | In the [[Brothers Grimm]] fairy tale ''Der Schuhmacher und die Heinzelmännchen,'' a group of naked, one-foot-tall beings called ''Heinzelmännchen'' help a shoemaker in his work. When he rewards their work with little clothes, they are so delighted, that they run away and are never seen again. Even though ''Heinzelmännchen'' are akin to beings such as ''kobold''s and [[dwarf|dwarves]], the tale has been translated to English as ''The Shoemaker and the Elves'' (probably due to the similarity of the ''heinzelmännchen'' to Scottish brownies, a type of elf). | ||

| − | + | ===English elves=== | |

| + | [[Image:Poor little birdie teased by Richard Doyle.jpg|thumb|left|250px|''Poor little birdie teased,'' by [[Victorian era]] illustrator Richard Doyle depicts the traditional view of an elf from later English folklore as a diminutive woodland humanoid.]] | ||

| + | The elf makes many appearances in [[ballad]]s of English and Scottish origin, as well as folk tales, many involving trips to Elphame or Elfland (the ''Álfheim'' of Norse mythology), a mystical realm that is sometimes an eerie and unpleasant place. The elf is occasionally portrayed in a positive light, such as the Queen of Elphame in the ballad ''Thomas the Rhymer,'' but many examples exist of elves of sinister character, frequently bent on [[rape]] and [[murder]], as in the ''Tale of Childe Rowland,'' or the ballad ''Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight,'' in which the Elf-Knight bears away Isabel to murder her. | ||

| − | + | Most instances of elves in ballads are male; the only commonly encountered female elf is the Queen of Elfland, who appears in ''Thomas the Rhymer'' and ''The Queen of Elfland's Nourice,'' in which a woman is abducted to be a wet-nurse to the queen's baby, but promised that she may return home once the child is weaned. In none of these cases is the elf a sprightly character with [[pixie]]-like qualities. | |

| − | + | "Elf-shot" (or "elf-bolt or "elf-arrow") is a word found in [[Scotland]] and northern England, first attested in a manuscript of about the last quarter of the sixteenth century. Although first used in the sense of "sharp pain caused by elves," it later denotes [[Neolithic]] [[flint]] [[arrowhead]]s, which by the seventeenth century seem to have been attributed in Scotland to elvish folk, and which were used in healing rituals, and alleged to be used by [[witch]]es (and perhaps elves) to injure people and cattle.<ref>Alaric Hall, “Getting Shot of Elves: Healing, Witchcraft and Fairies in the Scottish Witchcraft Trials,” ''Folklore'' 116 (1) (2005): 19–36.</ref> So too a tangle in the hair was called an "elf-lock," as being caused by the mischief of the elves, and sudden paralysis was sometimes attributed to "elf-stroke." The following excerpt from a 1750 [[ode]] by [[William Collins]] attributes problems to elvish arrowheads: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>There every herd, by sad experience, knows<br/> | |

| − | + | How, winged with fate, their elf-shot arrows fly,<br/> | |

| + | When the sick ewe her summer food forgoes,<br/> | ||

| + | Or, stretched on earth, the heart-smit heifers lie.<ref>William Collins, [http://poetry.poetryx.com/poems/1850/ “An Ode on the Popular Superstitions off the Highlands of Scotland, Considered as the Subject of Poetry”] (1775). Retrieved March 25, 2007.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | [[Image:Rackham elves.jpg|250px|thumb|right|"To make my small elves coats; and some keep back." One of Arthur Rackham's illustrations to [[William Shakespeare]]'s ''A Midsummer Night's Dream.''<ref>William Shakespeare, [http://classics.freehomepage.com/midsummer/midsummer.html ''A Midsummer Night’s Dream,''] illustrated by [[Arthur Rackham]]. Retrieved June 11, 2007.</ref>]] | ||

| + | English folk tales of the early modern period typically portray elves as small, elusive people with mischievous personalities. They are not evil but might annoy humans or interfere in their affairs. They are sometimes said to be invisible. In this tradition, elves became more or less synonymous with the [[fairy|fairies]] that originated from [[Celtic mythology]], for example, the [[Wales|Welsh]] ''Ellyll'' (plural ''Ellyllon'') and ''Y Dynon Bach Têg,'' Lompa Lompa the Gigantic Elf from Plemurian Forest. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Significant for the distancing of the concept of elves from its mythological origins was the influence from literature. In [[Elizabeth I of England|Elizabethan]] [[England]], [[William Shakespeare]] imagined elves as little people. He apparently considered elves and fairies to be the same race. In ''Henry IV,'' part 1, act 2, scene 4, he has Falstaff call Prince Henry, "you starveling, you elfskin!" and in his ''A Midsummer Night's Dream,'' his elves are almost as small as [[insect]]s. On the other hand, [[Edmund Spenser]] applies ''elf'' to full-sized beings in ''The Faerie Queene.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The influence of Shakespeare and [[Michael Drayton]] made the use of "elf" and "fairy" for very small beings the norm. In [[Victorian era|Victorian]] literature, elves usually appeared in illustrations as tiny men and women with pointed ears and stocking caps. An example is [[Andrew Lang]]'s fairy tale ''Princess Nobody'' (1884), illustrated by [[Richard Doyle]], where fairies are tiny people with [[butterfly]] wings, whereas elves are tiny people with red stocking caps. There were exceptions to this rule however, such as the full-sized elves that appear in [[Edward Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany|Lord Dunsany]]'s ''The King of Elfland's Daughter.'' | ||

| − | + | ==Modern Representations of Elves== | |

| − | + | Outside of [[literature]], the most significant place elves hold in [[culture|cultural]] [[belief]]s and [[tradition]]s are in the [[United States]], [[Canada]], and [[England]] in modern children's [[folklore]] of [[Santa Claus]], which typically includes diminutive, green-clad elves with pointy ears and long noses as Santa's assistants. They wrap [[Christmas]] gifts and make toys in a workshop located in the [[North Pole]]. In this portrayal, elves slightly resemble nimble and delicate versions of the [[dwarf|dwarves]] of [[Norse mythology]]. The vision of the small but crafty Christmas elf has come to influence modern popular conception of elves, and sits side by side with the fantasy elves following [[J. R. R. Tolkien]]'s work. | |

| − | + | Modern [[fantasy]] literature has revived the elves as a race of semi-divine beings of human stature. Fantasy elves are different from Norse elves, but are more akin to that older mythology than to folktale elves. The grim Norse-style elves of human size introduced [[Poul Anderson]]'s fantasy novel ''The Broken Sword'' from 1954 are one of the first precursors to modern fantasy elves, although they are overshadowed (and preceded) by the elves of the twentieth-century [[philology|philologist]] and fantasy writer [[J. R. R. Tolkien]]. Though Tolkien originally conceived his elves as more [[fairy]]-like than they afterwards became, he also based them on the god-like and human-sized ''ljósálfar'' of Norse mythology. His elves were conceived as a race of beings similar in appearance to humans but fairer and wiser, with greater spiritual powers, keener senses, and a closer empathy with nature. They are great smiths and fierce warriors on the side of [[good]]. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'' (1954–1955) became astoundingly popular and was much imitated. In the 1960s and afterwards, elves similar to those in Tolkien's novels became staple characters in fantasy works and in fantasy role-playing games. | |

| − | == | + | ==Fairy tales involving elves== |

| + | All links retrieved December 13, 2011. | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm121.htm “Addlers & Menters”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm124.htm “Ainsel & Puck”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.authorama.com/english-fairy-tales-24.html “Childe Rowland”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.viking.ucla.edu/hrolf/ch11.html Elfin “Woman & Birth of Skuld”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm022.htm “Elle-Maids”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm024.htm “Elle-Maid near Ebeltoft”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm025.htm “Hans Puntleder”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/efft/efft48.htm “Hedley Kow”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm112.htm “Luck of Eden Hall”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.authorama.com/grimms-fairy-tales-39.html “The Elves & the Shoemaker”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm021.htm “Svend Faelling and the Elle-Maid”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/efft/efft08.htm “Wild Edric”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm084.htm “The Wild-women”] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/tfm/tfm020.htm “The Young Swain and the Elves”] | ||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | * | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | * Andersen, Hans Christian. [http://hca.gilead.org.il/elf_rose.html ''The Elf of the Rose.''] 1839. Retrieved December 30, 2021. |

| − | *Coghlan, Ronan. | + | * Andersen, Hans Christian. [http://www.andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/hersholt/TheRoseElf_e.html ''The Rose Elf,''] 1839. Retrieved December 30, 2021. |

| − | + | * Andersen, Hans Christian. [http://hca.gilead.org.il/elfin_hi.html ''The Elfin Hill.''] 1845. Retrieved December 30, 2021. | |

| − | + | * Coghlan, Ronan. ''Handbook of Fairies.'' Capall Bann Pub., 1999. ISBN 978-1898307914 | |

| − | * | + | * Hall, Alaric Timothy Peter, [http://www.alarichall.org.uk/ahphdprol.pdf "The Meanings of ''Elf'' and Elves in Medieval England"] (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Glasgow, 2004). ''alarichall.org.uk''. Retrieved December 30, 2021. |

| − | + | * Hellström, Anne Marie. ''En Krönika om Åsbro.'' Sweden, 1990. ISBN 9171947264 | |

| − | + | * Lang, Andrew. ''The Princess Nobody''. Dover Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-0486410203 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credit|Elf|90395748|}} |

Latest revision as of 10:19, 21 January 2023

An elf is a mystical creature found in Norse mythology that still survives in northern European folklore. Following their role in J.R.R. Tolkien's epic work The Lord of the Rings, elves have become staple characters of modern fantasy tales. There is great diversity in how elves have been portrayed; depending on the culture, elves can be depicted as youthful-seeming men and women of great beauty living in forests and other natural places, or small trickster creatures.

In early folklore, elves were generally possessed of supernatural abilities, often related to disease, which they could use for good (healing) or ill (sickening) depending on their relationship toward the person they were affecting. They also had some power over time, in that they could entrap human beings with their music and dance. Some elves were small, fairy-like creatures, possibly invisible, whereas others appeared human-sized. Generally they were long-lived, if not immortal. While many of these depictions are considered purely fictional, creatures such as elves, somewhat like human beings but with abilities that transcend the physical realm, find correlates in the angels and demons of many religions.

Etymology

Some linguists believe that elf, álf, and related words derive from the Proto-Indo-European root albh meaning "white," but the Oxford English Dictionary lists the earliest rendition of the name as originating from Old High German, before being transmitted into Middle High German, West Saxon, and then finally arriving in English in its current form.[1] Though the exact etymology may be a contention among linguists, it is clear that nearly every culture in European history has had its own name for the similar representation of the creatures commonly called elves. "Elf" can be pluralized both as "elves" and "elfs." Something associated with elves or the qualities of elves is described by the adjectives "elven," "elvish," "elfin," or "elfish."

Cultural Variations

Norse

The earliest preserved description of elves comes from Norse mythology. In Old Norse they are called álfr, plural álfar. Although the concept itself is not entirely clear in surviving texts and records, elves appear to have been understood as powerful and beautiful human-sized beings. They are commonly referred to collectively as semi-divine beings associated with fertility as well as the cult of the ancestors. As such, elves appear similar to the animistic belief in spirits of nature and of the deceased, common to nearly all human religions; something that is true also for the Old Norse belief in fylgjur and vörðar ("follower" and "warden" spirits, respectively).

The earliest references come from Skaldic poetry, the Poetic Edda, and legendary sagas. Here elves are linked with the Æsir (or Aesir), particularly through the common phrase "Æsir and the elves," which presumably means "all the gods." The elves have also been compared or identified with the Vanir (fertility gods) by some scholars.[2] However, in the Alvíssmál ("The Sayings of All-Wise"), the elves are considered distinct from both the Vanir and the Æsir, as revealed by a series of comparative names in which Æsir, Vanir, and elves are given their own versions for various words in a reflection of their individual racial preferences. Possibly, the words designate a difference in status between the major fertility gods (the Vanir) and the minor ones (the elves). Grímnismál relates that the Van Freyr was the lord of Álfheimr (meaning "elf-world"), the home of the light-elves. Lokasenna relates that a large group of Æsir and elves had assembled at Ægir's court for a banquet. Several minor forces, the servants of gods, are presented such as Byggvir and Beyla, who belonged to Freyr, the lord of the elves, and they were probably elves, since they were not counted among the gods. Two other mentioned servants were Fimafeng (who was murdered by Loki) and Eldir.

Some speculate that Vanir and elves belong to an earlier Nordic Bronze Age religion of Scandinavia, and were later replaced by the Æsir as main gods. Others (most notably Georges Dumézil) have argued that the Vanir were the gods of the common Norsemen, and the Æsir those of the priest and warrior castes.

In Scandinavian folklore, which is a later blend of Norse mythology and elements of Christian mythology, an elf is called elver in Danish, alv in Norwegian, and alv or älva in Swedish (the first form being masculine, the second feminine).

In Denmark and Sweden, the elves appear as beings distinct from the vetter, even though the border between them is diffuse. The alf found in the fairy tale The Elf of the Rose by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen is so tiny that he can have a rose blossom for his home, and has "wings that reached from his shoulders to his feet." Yet, Andersen also wrote about elvere in The Elfin Hill, which were more like those of traditional Danish folklore, who were beautiful females, living in hills and boulders, capable of dancing a man to death. Like the huldra in Norway and Sweden, they are hollow when seen from the back.

The elves are typically pictured as fair-haired, white-clad, and, like most creatures in Scandinavian folklore, can be extremely dangerous when offended. In the stories, they often play the role of disease-spirits. The most common, though also most harmless case, was various irritating skin rashes, which were called älvablåst (elven blow) and could be cured by a forceful counter-blow (a handy pair of bellows was most useful for this purpose). Skålgropar, a particular kind of petroglyph found in Scandinavia, were known in older times as älvkvarnar (elven mills), pointing to their believed usage. One could appease the elves by offering them a treat (preferably butter) placed into an elven mill—perhaps a custom with roots in the Old Norse álfablót.

The elves could be seen dancing over meadows, particularly at night and on misty mornings. They left a kind of circle where they had danced, which were called älvdanser (elf dances) or älvringar (elf circles), and to urinate in one was thought to cause venereal disease. Typically, the circles consisted of a ring of small mushrooms, but there was also another kind of elf circle:

On lake shores, where the forest met the lake, you could find elf circles. They were round places where the grass had been flattened like a floor. Elves had danced there. By Lake Tisaren, I have seen one of those. It could be dangerous and one could become ill if one had trodden over such a place or if one destroyed anything there.[3]

If a human being watched the dance of the elves, he would discover that even though only a few hours seemed to have passed, many years had passed in the real world, a remote parallel to the Irish sídhe. In a song from the late Middle Ages about Olaf Liljekrans, the elven queen invites him to dance. He refuses, knowing what will happen if he joins the dance and he is also on his way home to his own wedding. The queen offers him gifts, but he declines. She threatens to kill him if he does not join, but he rides off and dies of the disease she sent upon him, and his young bride dies of a broken heart.[4]

However, the elves were not exclusively young and beautiful. In the Swedish folktale Little Rosa and Long Leda, an elvish woman (älvakvinna) arrives in the end and saves the heroine, Little Rose, on condition that the king's cattle no longer graze on her hill. She is described as an old woman and by her aspect people saw that she belonged to the subterraneans.[5]

German elves

What remained of the belief in elves in German folklore was the idea that they were mischievous pranksters that could cause disease to cattle and people, and bring bad dreams to sleepers. The German word for "nightmare," Albtraum, means "elf dream." The archaic form Albdruck means "elf pressure." It was believed that nightmares were a result of an elf sitting on the dreamer's head. This aspect of German elf-belief largely corresponds to the Scandinavian belief in the mara. It is also similar to the legends regarding incubi and succubi demons.[2]

The legend of Der Erlkönig appears to have originated in fairly recent times in Denmark. The Erlkönig's nature has been the subject of some debate. The name translates literally from the German as "Alder King" rather than its common English translation, "Elf King" (which would be rendered as Elfenkönig in German). It has often been suggested that Erlkönig is a mistranslation from the original Danish elverkonge or elverkonge, which does mean "elf king."

According to German and Danish folklore, the Erlkönig appears as an omen of death, much like the banshee in Irish mythology. Unlike the banshee, however, the Erlkönig will appear only to the person about to die. His form and expression also tells the person what sort of death they will have: a pained expression means a painful death, a peaceful expression means a peaceful death. This aspect of the legend was immortalized by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his poem Der Erlkönig, based on "Erlkönigs Tochter" ("Erlkönig's Daughter"), a Danish work translated into German by Johann Gottfried Herder. The poem was later set to music by Franz Schubert.

In the Brothers Grimm fairy tale Der Schuhmacher und die Heinzelmännchen, a group of naked, one-foot-tall beings called Heinzelmännchen help a shoemaker in his work. When he rewards their work with little clothes, they are so delighted, that they run away and are never seen again. Even though Heinzelmännchen are akin to beings such as kobolds and dwarves, the tale has been translated to English as The Shoemaker and the Elves (probably due to the similarity of the heinzelmännchen to Scottish brownies, a type of elf).

English elves

The elf makes many appearances in ballads of English and Scottish origin, as well as folk tales, many involving trips to Elphame or Elfland (the Álfheim of Norse mythology), a mystical realm that is sometimes an eerie and unpleasant place. The elf is occasionally portrayed in a positive light, such as the Queen of Elphame in the ballad Thomas the Rhymer, but many examples exist of elves of sinister character, frequently bent on rape and murder, as in the Tale of Childe Rowland, or the ballad Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight, in which the Elf-Knight bears away Isabel to murder her.

Most instances of elves in ballads are male; the only commonly encountered female elf is the Queen of Elfland, who appears in Thomas the Rhymer and The Queen of Elfland's Nourice, in which a woman is abducted to be a wet-nurse to the queen's baby, but promised that she may return home once the child is weaned. In none of these cases is the elf a sprightly character with pixie-like qualities.

"Elf-shot" (or "elf-bolt or "elf-arrow") is a word found in Scotland and northern England, first attested in a manuscript of about the last quarter of the sixteenth century. Although first used in the sense of "sharp pain caused by elves," it later denotes Neolithic flint arrowheads, which by the seventeenth century seem to have been attributed in Scotland to elvish folk, and which were used in healing rituals, and alleged to be used by witches (and perhaps elves) to injure people and cattle.[6] So too a tangle in the hair was called an "elf-lock," as being caused by the mischief of the elves, and sudden paralysis was sometimes attributed to "elf-stroke." The following excerpt from a 1750 ode by William Collins attributes problems to elvish arrowheads:

There every herd, by sad experience, knows

How, winged with fate, their elf-shot arrows fly,

When the sick ewe her summer food forgoes,

Or, stretched on earth, the heart-smit heifers lie.[7]

English folk tales of the early modern period typically portray elves as small, elusive people with mischievous personalities. They are not evil but might annoy humans or interfere in their affairs. They are sometimes said to be invisible. In this tradition, elves became more or less synonymous with the fairies that originated from Celtic mythology, for example, the Welsh Ellyll (plural Ellyllon) and Y Dynon Bach Têg, Lompa Lompa the Gigantic Elf from Plemurian Forest.

Significant for the distancing of the concept of elves from its mythological origins was the influence from literature. In Elizabethan England, William Shakespeare imagined elves as little people. He apparently considered elves and fairies to be the same race. In Henry IV, part 1, act 2, scene 4, he has Falstaff call Prince Henry, "you starveling, you elfskin!" and in his A Midsummer Night's Dream, his elves are almost as small as insects. On the other hand, Edmund Spenser applies elf to full-sized beings in The Faerie Queene.

The influence of Shakespeare and Michael Drayton made the use of "elf" and "fairy" for very small beings the norm. In Victorian literature, elves usually appeared in illustrations as tiny men and women with pointed ears and stocking caps. An example is Andrew Lang's fairy tale Princess Nobody (1884), illustrated by Richard Doyle, where fairies are tiny people with butterfly wings, whereas elves are tiny people with red stocking caps. There were exceptions to this rule however, such as the full-sized elves that appear in Lord Dunsany's The King of Elfland's Daughter.

Modern Representations of Elves

Outside of literature, the most significant place elves hold in cultural beliefs and traditions are in the United States, Canada, and England in modern children's folklore of Santa Claus, which typically includes diminutive, green-clad elves with pointy ears and long noses as Santa's assistants. They wrap Christmas gifts and make toys in a workshop located in the North Pole. In this portrayal, elves slightly resemble nimble and delicate versions of the dwarves of Norse mythology. The vision of the small but crafty Christmas elf has come to influence modern popular conception of elves, and sits side by side with the fantasy elves following J. R. R. Tolkien's work.

Modern fantasy literature has revived the elves as a race of semi-divine beings of human stature. Fantasy elves are different from Norse elves, but are more akin to that older mythology than to folktale elves. The grim Norse-style elves of human size introduced Poul Anderson's fantasy novel The Broken Sword from 1954 are one of the first precursors to modern fantasy elves, although they are overshadowed (and preceded) by the elves of the twentieth-century philologist and fantasy writer J. R. R. Tolkien. Though Tolkien originally conceived his elves as more fairy-like than they afterwards became, he also based them on the god-like and human-sized ljósálfar of Norse mythology. His elves were conceived as a race of beings similar in appearance to humans but fairer and wiser, with greater spiritual powers, keener senses, and a closer empathy with nature. They are great smiths and fierce warriors on the side of good. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955) became astoundingly popular and was much imitated. In the 1960s and afterwards, elves similar to those in Tolkien's novels became staple characters in fantasy works and in fantasy role-playing games.

Fairy tales involving elves

All links retrieved December 13, 2011.

- “Addlers & Menters”

- “Ainsel & Puck”

- “Childe Rowland”

- Elfin “Woman & Birth of Skuld”

- “Elle-Maids”

- “Elle-Maid near Ebeltoft”

- “Hans Puntleder”

- “Hedley Kow”

- “Luck of Eden Hall”

- “The Elves & the Shoemaker”

- “Svend Faelling and the Elle-Maid”

- “Wild Edric”

- “The Wild-women”

- “The Young Swain and the Elves”

Notes

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), s.v. “Elf.”

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Alaric Timothy Peter Hall, "The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Glasgow, 2004). Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ↑ An account given in 1926, found in Anne Marie Hellström, En Krönika om Åsbro. (Sweden: 1990, ISBN 9171947264), 36.

- ↑ Thomas Keightley. 1870. The Fairy Mythology. provides two translated versions of the song: Thomas Keightley, “Sir Olof in Elve-Dance”' and “The Elf-Woman and Sir Olof,” in The Fairy Mythology (London, H.G. Bohn, 1870). sacredtexts.com. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ↑ “Lilla Rosa och Långa Leda,” Svenska folksagor (Stockholm, Almquist & Wiksell Förlag AB, 1984), 158.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, “Getting Shot of Elves: Healing, Witchcraft and Fairies in the Scottish Witchcraft Trials,” Folklore 116 (1) (2005): 19–36.

- ↑ William Collins, “An Ode on the Popular Superstitions off the Highlands of Scotland, Considered as the Subject of Poetry” (1775). Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ↑ William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andersen, Hans Christian. The Elf of the Rose. 1839. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Andersen, Hans Christian. The Rose Elf, 1839. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Andersen, Hans Christian. The Elfin Hill. 1845. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Coghlan, Ronan. Handbook of Fairies. Capall Bann Pub., 1999. ISBN 978-1898307914

- Hall, Alaric Timothy Peter, "The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Glasgow, 2004). alarichall.org.uk. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Hellström, Anne Marie. En Krönika om Åsbro. Sweden, 1990. ISBN 9171947264

- Lang, Andrew. The Princess Nobody. Dover Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-0486410203

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.