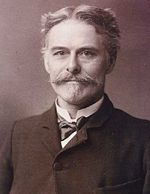

Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840–April 12, 1897) was an American paleontologist and comparative anatomist, as well as a noted herpetologist and ichthyologist. He discovered and named many fossils, and was a regarded as a brilliant scientist. He published more than 1,200 scientific papers, a record that he holds to this day.

E. D. Cope was particularly well known for his competition with Othniel Charles Marsh, the so-called Bone Wars. Their fierce rivalry to discover, describe, and name fossils, discovered mostly in the American West, resulted in the numerous new species of dinosaurs. However, their animosity and desire for the glory of finding and naming spectacular fossils also manifested in efforts to destroy each other's reputation and a rush to publish and describe organisms, which resulted in notable errors. There were also allegations of bribery, spying, stealing of fossils, and treaty violations, and it is claimed that Marsh even dynamited a fossil site rather than let it fall into Cope's hands.

While Cope and Marsh's discoveries made their names legends and helped define a new field of study, they are also renowned for their less noble actions. Their public behavior harmed the reputation of American paleontogy and it is not known how many critical fossils were destroyed.

Life

| “ | These strange creatures flapped their leathery wings over the waves, and often plunging, seized many an unsuspecting fish; or, soaring, at a safe distance, viewed the sports and combats of more powerful saurians of the sea. At night-fall, we may imagine them trooping to the shore, and suspending themselves to the cliffs by the claw-bearing fingers of their wing-limbs. | ” |

—Cope, describing the Pterodactyl | ||

Cope was born in Philadelphia to Quaker parents. At an early age he became interested in natural history, and in 1859 communicated a paper on the Salamandridae to the Academy of Natural Sciences at Philadelphia.

It was about this time that he became affiliated with the Megatherium Club at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. He was educated partly in the University of Pennsylvania and, after further study and travel in Europe, was appointed curator to the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1865, a post which he held until 1873. From 1864–1867 he was professor of natural science at Haverford College, and in 1889 he was appointed professor of geology and paleontology by the University of Pennsylvania.

His speciality was the study of the American fossil vertebrata. From 1871–1877 he carried on explorations of the Cretaceous strata of Kansas, and the Tertiary in Wyoming and Colorado. He made known at least 1,000 new species in his lifetime, as well as many genera of extinct vertebrata. Among these were some of the oldest known mammals, obtained in New Mexico, and 56 species of dinosaur, including Camarasaurus, Amphicoelias, and Coelophysis. He was an incredibly prolific publisher, producing more than 1,200 scientific papers in his lifetime. He served on the U.S. Geological Survey in New Mexico (1874), Montana (1875), and in Oregon and Texas (1877). He was also one of the editors of the American Naturalist. He died in Philadelphia.

Cope requested in his will that his remains be used as the holotype of Homo sapiens. Some efforts were made in this direction, but the skeleton was found unsuitable to be a type specimen due to disease. Later, W.T. Stearn (1959) designated Linnaeus himself as the lectotype of H. sapiens. Maverick paleontologist Robert Bakker declared his intention to describe Cope's skull as a type specimen, but never published this (a 1994 book by Louis Psihoyos attributed a supposed citation to Bakker in "The Journal of the Wyoming Geological Society," but this does not exist). Such a publication, even if it did exist, would have been invalidated by Stearn's prior designation, but - to make matters more confusing - the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (which did not exist until 1961) also invalidates Stearn's designation, and makes it altogether impossible for a neotype to be validly designated for H. sapiens (ICZN Article 75.3).

Bone Wars

Cope's competition with Othniel Charles Marsh for the discovery of new fossils became known as the Bone Wars.

Cope's law

In evolutionary biology, Cope's rule states that population lineages tend to increase body size over geological time. It is named for Edward Drinker Cope. The horse family, Equidae, is often used to illustrate the rule, with small animals evolving into larger ones; but critics such as Stephen Jay Gould point out a number of shortcomings of this example.

Cope's rule is interesting because it appears to make the apparently paradoxical suggestion that possession of large body size favours the individual but renders the clade more susceptible to extinction.

Writing in Science, Blaire Van Valkenburgh of UCLA and coworkers state:

Cope's rule, or the evolutionary trend toward larger body size, is common among mammals. Large size enhances the ability to avoid predators and capture prey, enhances reproductive success, and improves thermal efficiency. Moreover, in large carnivores, interspecific competition for food tends to be relatively intense, and bigger species tend to dominate and kill smaller competitors. Progenitors of hypercarnivorous lineages may have started as relatively small-bodied scavengers of large carcasses, similar to foxes and coyotes, with selection favoring both larger size and enhanced craniodental adaptations for meat eating. Moreover, the evolution of predator size is likely to be influenced by changes in prey size, and a significant trend toward larger size has been documented for large North American mammals, including both herbivores and carnivores, in the Cenozoic.

—(Science, Vol 30 DOI:10.1126/science.1102417)

Cope's rule has come under sustained criticism, including the observation that counterexamples to Cope's rule are common throughout geological time. Critics also point out that the so-called rule is worthless without a mechanism; palaeontologist Johnathan R. Wigner has stated that "Cope's Rule is a twisted version of the ... historical-narrative (that is, a just-so story). It takes a perceived historical trend and tries to explain it."

Reference

Stearn, William T. (1959). The Background of Linnaeus's Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology. Systematic Zoology 8:4–22.

See also

- Cope's law

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.