Cyrillic script

| Cyrillic script | |

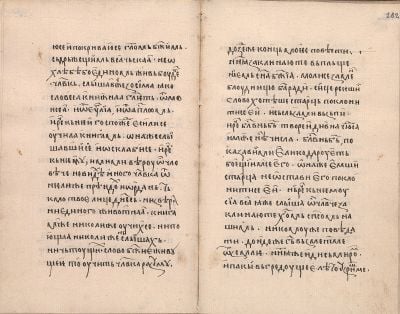

1780s Romanian text (Lord's Prayer) in Cyrillic script | |

| Script type | |

|---|---|

Time period | Earliest variants exist c. 893[1] – c. 940 |

| Official script | 7 sovereign states |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs[2]

|

Child systems | Old Permic script |

Sister systems | |

Names: Belarusian: кірыліца, Bulgarian: кирилица [ˈkirilit͡sɐ], Macedonian: кирилица [kiˈrilit͡sa], Russian: кириллица Russian pronunciation: [kʲɪˈrʲilʲɪtsə], Serbian: ћирилица, Ukrainian: кирилиця | |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. | |

The Cyrillic script, Slavonic script, or the Slavic script, is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian, and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Central Asia, North Asia, and East Asia. Its name derives from Saint Cyril, who along with his brother, Saint Methodius, are said to be the inspiration for the script.

Etymology

Since the script was conceived and popularized by the followers of Cyril and Methodius, rather than by Cyril and Methodius themselves, its name denotes homage rather than authorship. The name "Cyrillic" can be confusing for those who are not familiar with the script's history, because it does not identify a country of origin (in contrast to the "Greek alphabet"). Among the general public, it is often called "the Russian alphabet," because Russian is the most popular and influential alphabet based on the script. This does not necessarily sit well with non-Russian Slavs. A Bulgarian intellectuals, Stefan Tsanev, suggested that the Cyrillic script be called the "Bulgarian alphabet" instead, for the sake of historical accuracy.[4]

In Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian, Serbian, Czech and Slovak, the Cyrillic alphabet is also known as azbuka, derived from the old names of the first two letters of most Cyrillic alphabets (just as the term alphabet came from the first two Greek letters alpha and beta). In Czech and Slovak, which have never used Cyrillic, "azbuka" refers to Cyrillic and contrasts with "abeceda," which refers to the local Latin script and is composed of the names of the first letters (A, B, C, and D). In Russian, syllabaries, especially the Japanese kana, are commonly referred to as 'syllabic azbukas' rather than "syllabic scripts."

History

Timeline

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

- Hieratic 32 c. BCE

- Demotic 7 c. BCE

- Meroitic 3 c. BCE

- Demotic 7 c. BCE

- Proto-Sinaitic 19 c. BCE

- Ugaritic 15 c. BCE

- Epigraphic South Arabian 9 c. BCE

- Ge’ez 5–6 c. BCE

- Phoenician 12 c. BCE

- Paleo-Hebrew 10 c. BCE

- Samaritan 6 c. BCE

- Libyco-Berber 3 c. BCE

- Tifinagh

- Paleohispanic (semi-syllabic) 7 c. BCE

- Aramaic 8 c. BCE

- Kharoṣṭhī 4 c. BCE

- Brāhmī 4 c. BCE

- Brahmic family (see)

- E.g. Tibetan 7 c. CE

- Hangul (core letters only) 1443

- Devanagari 13 c. CE

- Canadian syllabics 1840

- E.g. Tibetan 7 c. CE

- Brahmic family (see)

- Hebrew 3 c. BCE

- Pahlavi 3 c. BCE

- Avestan 4 c. CE

- Palmyrene 2 c. BCE

- Syriac 2 c. BCE

- Nabataean 2 c. BCE

- Arabic 4 c. CE

- Sogdian 2 c. BCE

- Nabataean 2 c. BCE

- Orkhon (old Turkic) 6 c. CE

- Old Hungarian c. 650

- Old Uyghur

- Mongolian 1204

- N'Ko 20 c. CE

- Old Uyghur

- Old Hungarian c. 650

- Mandaic 2 c. CE

- Greek 8 c. BCE

- Etruscan 8 c. BCE

- Latin 7 c. BCE

- Cherokee (syllabary; letter forms only) c. 1820

- Runic 2 c. CE

- Ogham (origin uncertain) 4 c. CE

- Latin 7 c. BCE

- Coptic 3 c. CE

- Gothic 3 c. CE

- Armenian (origin uncertain) 405

- Georgian (origin uncertain) c. 430

- Glagolitic (origin uncertain) 862

- Cyrillic c. 940

- Old Permic 1372

- Etruscan 8 c. BCE

- Paleo-Hebrew 10 c. BCE

Thaana 18 c. (derived from Brahmi numerals)

Development

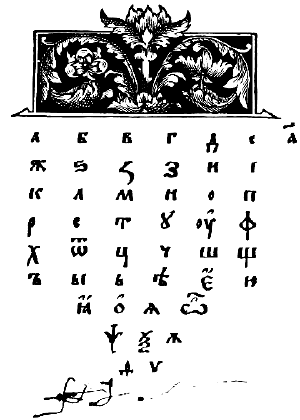

The Early Cyrillic alphabet was developed during the ninth century C.E. at the Preslav Literary School in the First Bulgarian Empire during the reign of tsar Simeon I the Great, probably by disciples of the two Byzantine brothers[6][7] Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius, who had previously created the Glagolitic script.[8] [9]

The Cyrillic script was created in the First Bulgarian Empire.[10] Modern scholars believe that the Early Cyrillic alphabet was created at the Preslav Literary School, the most important early literary and cultural center of the First Bulgarian Empire and of all Slavs:

Unlike the Churchmen in Ohrid, Preslav scholars were much more dependent upon Greek models and quickly abandoned the Glagolitic scripts in favor of an adaptation of the Greek uncial to the needs of Slavic, which is now known as the Cyrillic alphabet.[11]

A number of prominent Bulgarian writers and scholars worked at the school, including Naum of Preslav until 893; Constantine of Preslav; Joan Ekzarh (also transcr. John the Exarch); and Chernorizets Hrabar, among others. The school was also a center of translation, mostly of Byzantine authors. The Cyrillic script is derived from the Greek uncial script letters, augmented by ligatures and consonants from the older Glagolitic alphabet for sounds not found in Greek. Glagolitic and Cyrillic were formalized by the Byzantine Saints Cyril and Methodius and their disciples, such as Saints Naum, Clement, Angelar, and Sava. They spread and taught Christianity in the whole of Bulgaria.[6][7][12][13][14] Paul Cubberley posits that although Cyril may have codified and expanded Glagolitic, it was his students in the First Bulgarian Empire under Tsar Simeon the Great that developed Cyrillic from the Greek letters in the 890s as a more suitable script for church books."[10]

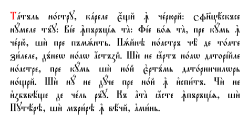

Cyrillic spread among other Slavic peoples, as well as among non-Slavic Vlachs. The earliest datable Cyrillic inscriptions have been found in the area of Preslav, in the medieval city itself and at nearby Patleina Monastery, both in present-day Shumen Province, as well as in the Ravna Monastery and in the Varna Monastery. The new script became the basis of alphabets used in various languages in Orthodox Church-dominated Eastern Europe, both Slavic and non-Slavic languages (such as Romanian, until the 1860s). For centuries, Cyrillic was also used by Catholic and Muslim Slavs (see Bosnian Cyrillic).

Cyrillic and Glagolitic were used for the Church Slavonic language, especially the Old Church Slavonic variant. Expressions such as "И is the tenth Cyrillic letter" typically refer to the order of the Church Slavonic alphabet. Not every Cyrillic alphabet uses every letter available in the script. The Cyrillic script came to dominate Glagolitic in the twelfth century.

The literature produced in Old Church Slavonic soon spread north from Bulgaria and became the lingua franca of the Balkans and Eastern Europe.[15][16][6][17]

Bosnian Cyrillic, widely known as Bosančica[18][19] is an extinct variant of the Cyrillic alphabet that originated in medieval Bosnia. Paleographers consider the earliest features of Bosnian Cyrillic script had likely begun to appear between the tenth or eleventh century, with the Humac tablet (a tablet written in Bosnian Cyrillic) thought to be the first such document using this type of script. It is believed to date from this period.[20] Bosnian Cyrillic was used continuously until the eighteenth century, with sporadic usage even taking place in the twentieth century.

With the orthographic reform of Saint Evtimiy of Tarnovo and other prominent representatives of the Tarnovo Literary School of the 14th and 15th centuries, such as Gregory Tsamblak and Constantine of Kostenets, the school influenced Russian, Serbian, Wallachian and Moldavian medieval culture. This is known in Russia as the second South-Slavic influence.

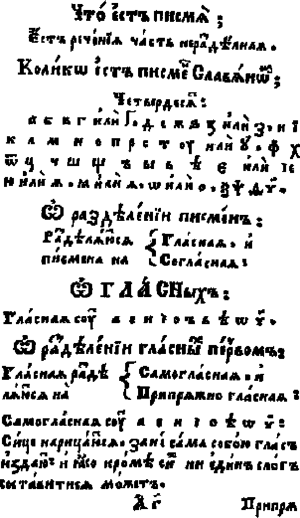

In the early eighteenth century, the Cyrillic script used in Russia was heavily reformed by Peter the Great, who had recently returned from his Grand Embassy in Western Europe. The new letterforms, called the Civil script, became closer to those of the Latin alphabet. Several archaic letters were abolished and several new letters designed by Peter himself were introduced. Letters became distinguished between upper and lower case. West European typography culture was also adopted.[21] The pre-reform letterforms, called 'Полуустав', were notably retained in Church Slavonic and are sometimes used in Russian even today, especially if one wants to give a text a 'Slavic' or 'archaic' feel.

The alphabet used for the modern Church Slavonic language in Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic rites still resembles early Cyrillic. However, over the course of the following millennium, Cyrillic adapted to changes in spoken language, developed regional variations to suit the features of national languages, and was subjected to academic reform and political decrees. A notable example of such linguistic reform can be attributed to Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, who updated the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet by removing certain graphemes no longer represented in the vernacular and introducing graphemes specific to Serbian (i.e. Љ Њ Ђ Ћ Џ Ј), distancing it from Church Slavonic alphabet in use prior to the reform. Today, many languages in the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and northern Eurasia are written in Cyrillic alphabets.

With the accession of Bulgaria to the European Union on January 1, 2007, Cyrillic became the third official script of the European Union, following the Latin and Greek alphabets.[22]

As of 2019, around 250 million people in Eurasia use Cyrillic as the official script for their national languages, with Russia accounting for about half of them.

Letters

Cyrillic script spread throughout the East Slavic and some South Slavic territories, adopted for writing local languages such as Old East Slavic. Its adaptation to local languages produced a number of Cyrillic alphabets.

| А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ж | Ꙃ[24] | Ꙁ | И | І | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | ОѴ[25] | Ф |

| Х | Ѡ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | ЪІ[26] | Ь | Ѣ | Ꙗ | Ѥ | Ю | Ѫ | Ѭ | Ѧ | Ѩ | Ѯ | Ѱ | Ѳ | Ѵ | Ҁ[6] |

Capital and lowercase letters were not distinguished in old manuscripts.

Yeri (Ы) was originally a ligature of Yer and I (Ъ + І = Ы). Iotation was indicated by ligatures formed with the letter І: Ꙗ (not an ancestor of modern Ya, Я, which is derived from Ѧ), Ѥ, Ю (ligature of І and ОУ), Ѩ, Ѭ. Sometimes different letters were used interchangeably, for example И = І = Ї, as were typographical variants like О = Ѻ. There were also commonly used ligatures like ѠТ = Ѿ.

The letters also had numeric values, based not on Cyrillic alphabetical order, but inherited from the letters' Greek ancestors.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| А | В | Г | Д | Є (Е) | Ѕ (Ꙃ, Ꙅ) | З (Ꙁ) | И | Ѳ |

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

| І (Ї) | К | Л | М | Н | Ѯ (Ч) | Ѻ (О) | П | Ч (Ҁ) |

| 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 |

| Р | С | Т | Ѵ (Ѵ, Оу, Ꙋ) | Ф | Х | Ѱ | Ѡ (Ѿ, Ꙍ) | Ц (Ѧ) |

The early Cyrillic alphabet is difficult to represent on computers. Many of the letterforms differed from those of modern Cyrillic, varied a great deal in manuscripts, and changed over time. Few fonts include glyphs sufficient to reproduce the alphabet. In accordance with Unicode policy, the standard does not include letterform variations or ligatures found in manuscript sources unless they can be shown to conform to the Unicode definition of a character.

The Unicode 5.1 standard, released on April 4, 2008 greatly improves computer support for the early Cyrillic and the modern Church Slavonic language. In Microsoft Windows, the Segoe UI user interface font is notable for having complete support for the archaic Cyrillic letters since Windows 8.

Currency signs

Some currency signs have derived from Cyrillic letters:

- The Ukrainian hryvnia sign (₴) is from the cursive minuscule Ukrainian Cyrillic letter He (г).

- The Russian ruble sign (₽) from the majuscule Р.

- The Kyrgyzstani som sign (с) from the majuscule С (es)

- The Kazakhstani tenge sign (₸) from Т

- The Mongolian tögrög sign (₮) from Т

Letterforms and typography

The development of Cyrillic typography passed directly from the medieval stage to the late Baroque, without a Renaissance phase like Western Europe. Late Medieval Cyrillic letters (categorized as vyaz' and still found on many icon inscriptions today) show a marked tendency to be very tall and narrow, with strokes often shared between adjacent letters.

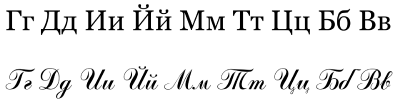

Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia, mandated the use of westernized letter forms (ru) in the early eighteenth century. Over time, these were largely adopted in the other languages that use the script. Unlike the majority of modern Greek fonts that retained their own set of design principles for lower-case letters (such as the placement of serifs, the shapes of stroke ends, and stroke-thickness rules), modern Cyrillic fonts are much the same as modern Latin fonts of the same font family, although Greek capital letters do use Latin design principles. The development of some Cyrillic computer typefaces from Latin ones has also contributed to the visual Latinization of Cyrillic type.

Lowercase forms

Cyrillic uppercase and lowercase letter forms are not as differentiated as in Latin typography. Upright Cyrillic lowercase letters are essentially small capitals (with exceptions: Cyrillic ⟨а⟩, ⟨е⟩, ⟨і⟩, ⟨ј⟩, ⟨р⟩, and ⟨у⟩ adopted Western lowercase shapes, lowercase ⟨ф⟩ is typically designed under the influence of Latin ⟨p⟩, lowercase ⟨б⟩, ⟨ђ⟩ and ⟨ћ⟩ are traditional handwritten forms, although a good-quality Cyrillic typeface will still include separate small-cap glyphs.[27]

Cyrillic fonts, as well as Latin ones, have roman and italic types (practically all popular modern fonts include parallel sets of Latin and Cyrillic letters, where many glyphs, uppercase as well as lowercase, are shared by both). However, the native font terminology in most Slavic languages (for example, in Russian) does not use the words "roman" and "italic" in this sense. Instead, the nomenclature follows German naming patterns:

- Roman type is called pryamoy shrift ("upright type") – compare with Normalschrift ("regular type") in German

- Italic type is called kursiv ("cursive") or kursivniy shrift ("cursive type") – from the German word Kursive, meaning italic typefaces and not cursive writing

- Cursive handwriting is rukopisniy shrift ("handwritten type") – in German: Kurrentschrift or Laufschrift, both meaning literally 'running type'

- A (mechanically) sloped oblique type of sans-serif faces is naklonniy shrift ("sloped" or "slanted type").

- A boldfaced type is called poluzhirniy shrift ("semi-bold type"), because there existed fully boldfaced shapes that have been out of use since the beginning of the twentieth century.

Italic and cursive forms

Similarly to Latin fonts, italic and cursive types of many Cyrillic letters (typically lowercase; uppercase only for handwritten or stylish types) are very different from their upright roman types. In certain cases, the correspondence between uppercase and lowercase glyphs does not coincide in Latin and Cyrillic fonts: for example, italic Cyrillic ⟨т⟩ is the lowercase counterpart of ⟨Т⟩ not of ⟨М⟩.

| upright | а | б | в | г | д | е | ё | ж | з | и | й | к | л | м | н | о | п | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| italic | а | б | в | г | д | е | ё | ж | з | и | й | к | л | м | н | о | п | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

Note: in some fonts or styles, ⟨д⟩, i.e. the lowercase italic Cyrillic ⟨д⟩, may look like Latin ⟨g⟩, and ⟨т⟩, i.e. lowercase italic Cyrillic ⟨т⟩, may look like small-capital italic ⟨T⟩.

In Standard Serbian, as well as in Macedonian,[28] some italic and cursive letters are allowed to be different to more closely resemble the handwritten letters. The regular (upright) shapes are generally standardized in small caps form.[29]

| Russian | а | б | в | г | д | — | е | ж | з | и | й | — | к | л | — | м | н | — | о | п | р | с | т | — | у | ф | х | ц | ч | — | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbian | а | б | в | г | д | ђ | е | ж | з | и | — | ј | к | л | љ | м | н | њ | о | п | р | с | т | ћ | у | ф | х | ц | ч | џ | ш | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| faux | а | δ | в | ī | ɡ | ђ | е | ж | з | и | — | ј | к | л | љ | м | н | њ | о | ū | р | с | ш̄ | ћ | у | ф | х | ц | ч | џ | ш̱ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Notes: Depending on fonts available, the Serbian row may appear identical to the Russian row. Unicode approximations are used in the faux row to ensure it can be rendered properly across all systems.

In Bulgarian typography, many lowercase letterforms may more closely resemble the cursive forms on the one hand and Latin glyphs on the other hand, such as having an ascender or descender or by using rounded arcs instead of sharp corners.[30] Sometimes, uppercase letters may have a different shape as well, e.g. more triangular, Д and Л, like Greek delta Δ and lambda Λ.

| default | а | б | в | г | д | е | ж | з | и | й | к | л | м | н | о | п | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ь | ю | я |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgarian | а | б | в | г | д | е | ж | з | и | й | к | л | м | н | о | п | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ь | ю | я |

| faux | а | б | ϐ | ƨ | ɡ | е | жl | ȝ | u | ŭ | k | ʌ | м | н | о | n | р | с | m | у | ɸ | х | u̡ | ч | ɯ | ɯ̡ | ъ | ƅ | lo | я |

Notes: Depending on fonts available, the Bulgarian row may appear identical to the Russian row. Unicode approximations are used in the faux row to ensure it can be rendered properly across all systems. In some cases, such as ж with k-like ascender, no such approximation exists.

Accessing variant forms

Computer fonts typically default to the Central/Eastern, Russian letterforms, and require the use of OpenType Layout (OTL) features to display the Western, Bulgarian or Southern, Serbian/Macedonian forms. Depending on the choices of the font manufacturer, they may either be automatically activated by the local variant locl feature for text tagged with an appropriate language code, or the author needs to opt-in by activating a stylistic set ss## or character variant cv## feature. These solutions only enjoy partial support and may render with default glyphs in certain software configurations.

Cyrillic alphabets

Among others, Cyrillic is the standard script for writing the following languages:

- Slavic languages: Belarusian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian, Rusyn, Serbo-Croatian (Standard Serbian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin), Ukrainian

- Non-Slavic languages of Russia: Abaza, Adyghe, Avar, Azerbaijani (in Dagestan), Bashkir, Buryat, Chechen, Chuvash, Erzya, Ingush, Kabardian, Kalmyk, Karachay-Balkar, Kildin Sami, Komi, Mari, Moksha, Nogai, Ossetian (in North Ossetia–Alania), Romani, Sakha/Yakut, Tatar, Tuvan, Udmurt, Yuit (Yupik)

- Non-Slavic languages in other countries: Abkhaz, Aleut (now mostly in church texts), Dungan, Kazakh (to be replaced by Latin script by 2025[31]), Kyrgyz, Mongolian (to also be written with traditional Mongolian script by 2025), Tajik, Tlingit (now only in church texts), Turkmen (officially replaced by Latin script), Uzbek (also officially replaced by Latin script, but still in wide use), Yupik (in Alaska).

The Cyrillic script has also been used for languages of Alaska, Slavic Europe (except for Western Slavic and some Southern Slavic), the Caucasus, the languages of Idel-Ural, Siberia, and the Russian Far East.

The first alphabet derived from Cyrillic was Abur, used for the Komi language. Other Cyrillic alphabets include the Molodtsov alphabet for the Komi language and various alphabets for Caucasian languages.

Usage of Cyrillic versus other scripts

Latin script

A number of languages written in a Cyrillic alphabet have also been written in a Latin alphabet, such as Azerbaijani, Uzbek, Serbian and Romanian (in the Republic of Moldova until 1989, in the Danubian Principalities throughout the nineteenth century). After the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, some of the former republics officially shifted from Cyrillic to Latin. The transition is complete in most of Moldova (except the breakaway region of Transnistria, where Moldovan Cyrillic is official), Turkmenistan, and Azerbaijan. Uzbekistan still uses both systems, and Kazakhstan has officially begun a transition from Cyrillic to Latin (scheduled to be complete by 2025). The Russian government has mandated that Cyrillic must be used for all public communications in all federal subjects of Russia, to promote closer ties across the federation. This act was controversial for speakers of many Slavic languages; for others, such as Chechen and Ingush speakers, the law had political ramifications. The separatist Chechen government mandated a Latin script which is still used by many Chechens.

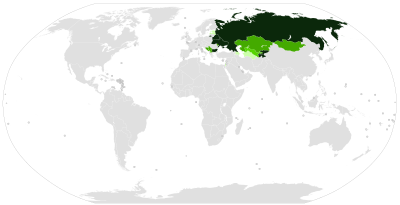

██ Sole official script ██ Co-official with another script (either because the official language is biscriptal, or the state is bilingual) ██ Being replaced with Latin, but is still in official use ██ Legacy script for the official language, or large minority use ██ Cyrillic is not widely used

Standard Serbian uses both the Cyrillic and Latin scripts. Cyrillic is nominally the official script of Serbia's administration according to the Serbian constitution; however, the law does not regulate scripts in standard language, or standard language itself by any means. In practice the scripts are equal, with Latin appearing more often in a less official capacity.[32]

The Zhuang alphabet, used between the 1950s and 1980s in portions of the People's Republic of China, used a mixture of Latin, phonetic, numeral-based, and Cyrillic letters. The non-Latin letters, including Cyrillic, were removed from the alphabet in 1982 and replaced with Latin letters that closely resembled the letters they replaced.

Romanization

There are various systems for Romanization of Cyrillic text, including transliteration to convey Cyrillic spelling in Latin letters, and transcription to convey pronunciation.

Standard Cyrillic-to-Latin transliteration systems include:

- Scientific transliteration, used in linguistics, is based on the Serbo-Croatian Latin alphabet.

- The Working Group on Romanization Systems[33] of the United Nations recommends different systems for specific languages. These are the most commonly used around the world.

- ISO 9:1995, from the International Organization for Standardization.

- American Library Association and Library of Congress Romanization tables for Slavic alphabets (ALA-LC Romanization), used in North American libraries.

- BGN/PCGN Romanization (1947), United States Board on Geographic Names & Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use).

- GOST 16876, a now defunct Soviet transliteration standard. Replaced by GOST 7.79, which is ISO 9 equivalent.

- Various informal romanizations of Cyrillic, which adapt the Cyrillic script to Latin and sometimes Greek glyphs for compatibility with small character sets.

See also: Romanization of Belarusian, Bulgarian, Kyrgyz, Russian, Macedonian and Ukrainian.

Cyrillization

Representing other writing systems with Cyrillic letters is called Cyrillization.

Computer encoding

Unicode

As of Unicode version 15.0, Cyrillic letters, including national and historical alphabets, are encoded across several blocks:

- Cyrillic: U+0400–U+04FF

- Cyrillic Supplement: U+0500–U+052F

- Cyrillic Extended-A: U+2DE0–U+2DFF

- Cyrillic Extended-B: U+A640–U+A69F

- Cyrillic Extended-C: U+1C80–U+1C8F

- Cyrillic Extended-D: U+1E030–U+1E08F

- Phonetic Extensions: U+1D2B, U+1D78

- Combining Half Marks: U+FE2E–U+FE2F

The characters in the range U+0400 to U+045F are essentially the characters from ISO 8859-5 moved upward by 864 positions. The characters in the range U+0460 to U+0489 are historic letters, not used now. The characters in the range U+048A to U+052F are additional letters for various languages that are written with Cyrillic script.

Unicode as a general rule does not include accented Cyrillic letters. A few exceptions include:

- combinations that are considered as separate letters of respective alphabets, like Й, Ў, Ё, Ї, Ѓ, Ќ (as well as many letters of non-Slavic alphabets);

- two most frequent combinations orthographically required to distinguish homonyms in Bulgarian and Macedonian: Ѐ, Ѝ;

- a few Old and New Church Slavonic combinations: Ѷ, Ѿ, Ѽ.

To indicate stressed or long vowels, combining diacritical marks can be used after the respective letter (for example, U+0301 ◌́ COMBINING ACUTE ACCENT: е́ у́ э́ etc.).

Some languages, including Church Slavonic, are still not fully supported.

Unicode 5.1, released on 4 April 2008, introduces major changes to the Cyrillic blocks. Revisions to the existing Cyrillic blocks, and the addition of Cyrillic Extended A (2DE0 ... 2DFF) and Cyrillic Extended B (A640 ... A69F), significantly improve support for the early Cyrillic alphabet, Abkhaz, Aleut, Chuvash, Kurdish, and Moksha.[34]

Other

Punctuation for Cyrillic text is similar to that used in European Latin-alphabet languages.

Other character encoding systems for Cyrillic:

- CP866 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by Microsoft for use in MS-DOS also known as GOST-alternative. Cyrillic characters go in their native order, with a "window" for pseudographic characters.

- ISO/IEC 8859-5 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by International Organization for Standardization

- KOI8-R – 8-bit native Russian character encoding. Invented in the USSR for use on Soviet clones of American IBM and DEC computers. The Cyrillic characters go in the order of their Latin counterparts, which allowed the text to remain readable after transmission via a 7-bit line that removed the most significant bit from each byte – the result became a very rough, but readable, Latin transliteration of Cyrillic. Standard encoding of early 1990s for Unix systems and the first Russian Internet encoding.

- KOI8-U – KOI8-R with addition of Ukrainian letters.

- MIK – 8-bit native Bulgarian character encoding for use in Microsoft DOS.

- Windows-1251 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by Microsoft for use in Microsoft Windows. The simplest 8-bit Cyrillic encoding – 32 capital chars in native order at 0xc0–0xdf, 32 usual chars at 0xe0–0xff, with rarely used "YO" characters somewhere else. No pseudographics. Former standard encoding in some Linux distributions for Belarusian and Bulgarian, but currently displaced by UTF-8.

- GOST-main.

- GB 2312 – Principally simplified Chinese encodings, but there are also the basic 33 Russian Cyrillic letters (in upper- and lower-case).

- JIS and Shift JIS – Principally Japanese encodings, but there are also the basic 33 Russian Cyrillic letters (in upper- and lower-case).

Keyboard layouts

Each language has its own standard keyboard layout, adopted from typewriters. With the flexibility of computer input methods, there are also transliterating or phonetic/homophonic keyboard layouts made for typists who are more familiar with other layouts, like the common English QWERTY keyboard. When practical Cyrillic keyboard layouts or fonts are unavailable, computer users sometimes use transliteration or look-alike "volapuk" encoding to type in languages that are normally written with the Cyrillic alphabet.

Notes

- ↑ Robert Auty, Handbook of Old Church Slavonic, Part II: Texts and Glossary (1960; London, U.K.: Athlone Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0485175189).

- ↑ "Oldest alphabet found in Egypt," BBC, November 15, 1999. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ↑ "Bdinski Zbornik" lib.ugent.be. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ↑ Stefan Tsanev, Български хроники, том 4 (Bulgarian Chronicles, Volume 4), (Sofia, BL, 2009,) 165.

- ↑ Провежда се международна конференция в гр. Опака за св. Антоний от Крепчанския манастир. Добротолюбие - Център за християнски, църковно-исторически и богословски изследвания, October 15, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Horace G. Lunt, "The Beginning of Written Slavic," Slavic Review 23(2) (June 1964): 212–219.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Leonid Ivan Strakhovsky, A Handbook of Slavic Studies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1949), 98.

- ↑ Francis Dvornik, The Slavs: Their Early History and Civilization (Boston, MA: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1956), 179. Retrieved March 22, 2023. "The Psalter and the Book of Prophets were adapted or "modernized" with special regard to their use in Bulgarian churches and it was in this school that the Glagolitic script was replaced by the so-called Cyrillic writing, which was more akin to the Greek uncial, simplified matters considerably and is still used by the Orthodox Slavs.'

- ↑ J. M. Hussey and Andrew Louth, "The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire," in Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-019161488), 100. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Paul Cubberley, "The Slavic Alphabets," in The World's Writing Systems, eds., Daniels and Bright (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0195079930).

- ↑ Florin Curta, Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. 2006, ISBN 978-0521815390), 221–222.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopaedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05, O.Ed. Saints Cyril and Methodius "Cyril and Methodius, Saints) 869 and 884, respectively, "Greek missionaries, brothers, called Apostles to the Slavs and fathers of Slavonic literature."

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Major alphabets of the world, Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets, 2008, O.Ed. "The two early Slavic alphabets, the Cyrillic and the Glagolitic, were invented by St. Cyril, or Constantine (c. 827–869), and St. Methodii (c. 825–884). These men from Thessaloniki who became apostles to the southern Slavs, whom they converted to Christianity."

- ↑ P.A. Hollingsworth, "Constantine the Philosopher," in Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0195046526), 507. "Constantine (Cyril) and his brother Methodius were the sons of the droungarios Leo and Maria, who may have been a Slav.

- ↑ Horace G. Lunt, "On the relationship of old Church Slavonic to the written language of early Rus'" Russian Linguistics 11(2–3) (January 1987).

- ↑ Alexander Schenker, The Dawn of Slavic (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0300058468), 185–186, 189–190.

- ↑ Benjamin W. Fortson, Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction (Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell, 2004, ISBN 978-1405103169), 374.

- ↑ Smail Balić, Die Kultur der Bosniaken, Supplement I: Inventar des bosnischen literarischen Erbes in orientalischen Sprachen (Vienna, AU: Adolf Holzhausens, 1978), 49–50, 111.

- ↑ Hamid Algar, The Literature of the Bosnian Muslims: a Quadrilingual Heritage (Kuala Lumpur, MY: Nadwah Ketakwaan Melalui Kreativiti, 1995), 254–68.

- ↑ Srećko M. Džaja & Ivan Lovrenović, Srećko M. Džaja vs. Ivan Lovrenović – polemika o kulturnom identitetu BiH Vijenac. Retrieved March 13, 2023. Published in whole in the Journal of Franciscan theology in Sarajevo, Bosna franciscana (42).

- ↑ "Civil Type and Kis Cyrillic," Type Journal, September 3, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ↑ Leonard Orban, "Cyrillic, the third official alphabet of the EU, was created by a truly multilingual European," European Commission, May 24, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ↑ А. Н. Стеценко. Хрестоматия по Старославянскому Языку (Readings in the Old Slavonic Language) (Moscow, RU: Enlightenment, 1984).

- ↑ Variant form: Also written S

- ↑ Variant form Ꙋ

- ↑ Variant form ЪИ

- ↑ "In Cyrillic, the difference between normal lower case and small caps is more subtle than it is in the Latin or Greek alphabets, ..." (p 32) and "in most Cyrillic faces, the lower case is close in color and shape to Latin small caps" (p 107). Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style, 2nd. ed. (1992; Vancouver, CA: Hartley & Marks, 2002, ISBN 0881791334), 32, 107.

- ↑ Makedonski Pravopis, Pravopis na makedonskiot jazik (Skopje, MK: Institut za makedonski jazik Krste Misirkov, 2017), 3. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ↑ Mitar Peshikan, Jovan Jerković and Mato Pižurica, Pravopis srpskoga jezika (Beograd, RS: Matica Srpska, 1994, ISBN 978-8636302965), 42.

- ↑ "Cyrillicsly: Two Cyrillics: a critical history I," Cargo. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ↑ "Alphabet soup as Kazakh leader orders switch from Cyrillic to Latin letters," The Guardian, October 30, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ↑ Nicole Itano, "Serbian signs of the times are not in Cyrillic," Christian Science Monitor, May 29, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ↑ United Nations Working Group on Geographical Names, "UNGEGN Working Group on Romanization Systems," Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ↑ Michael Everson, et. al., "IOS Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set," March 21, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Algar, Hamid. The Literature of the Bosnian Muslims: a Quadrilingual Heritage. Kuala Lumpur, MY: Nadwah Ketakwaan Melalui Kreativiti, 1995.

- Auty, Robert. Handbook of Old Church Slavonic, Part II: Texts and Glossary. London, U.K.: Athlone Press, 1977 (original 1960). ISBN 978-0485175189

- Balić, Smail. Die Kultur der Bosniaken, Supplement I: Inventar des bosnischen literarischen Erbes in orientalischen Sprachen. Vienna, AU: Adolf Holzhausens, 1978.

- Bringhurst, Robert. The Elements of Typographic Style, 2nd. ed. Vancouver, CA: Hartley & Marks, 2002 (original 1992). ISBN 0881791334

- Cubberley, Paul. "The Slavic Alphabets," in The World's Writing Systems, eds., Daniels and Bright. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0195079930

- Curta, Florin. Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0521815390

- Fortson, Benjamin W. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell, 2004. ISBN 978-1405103169

- Hollingsworth, P.A. "Constantine the Philosopher," in Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0195046526

- Hussey, J.M., and Andrew Louth. "The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire," in Oxford History of the Christian Church. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-019161488

- Lunt, Horace G. "The Beginning of Written Slavic," Slavic Review 23(2) (June 1964): 212–219.

- Lunt, Horace G. "On the relationship of old Church Slavonic to the written language of early Rus'" Russian Linguistics 11(2–3) (January 1987).

- Peshikan, Mitar, Jovan Jerković and Mato Pižurica. Pravopis srpskoga jezika. Beograd, RS: Matica Srpska, 1994. ISBN 978-8636302965

- Schenker, Alexander, The Dawn of Slavic. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0300058468.

- Strakhovsky, Leonid Ivan. A Handbook of Slavic Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1949.

- Стеценко. А. Н. Хрестоматия по Старославянскому Языку (Readings in the Old Slavonic Language). Moscow, RU: Enlightenment, 1984.

External links

Links retrieved March 19, 2023.

- The Cyrillic Charset Soup overview and history of Cyrillic charsets.

- Transliteration of Non-Roman Scripts, a collection of writing systems and transliteration tables

- History and development of the Cyrillic alphabet

- Cyrillic Alphabets of Slavic Languages review of Cyrillic charsets in Slavic Languages.

- data entry in Old Cyrillic / Стара Кирилица

- Cyrillic and its Long Journey East – NamepediA Blog, article about the Cyrillic script

- Unicode collation charts—including Cyrillic letters, sorted by shape

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.