|

|

| (43 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] |

| | [[Category:Law]] | | [[Category:Law]] |

| − | {{Claimed}} | + | [[Category:Sociology]] |

| | + | {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

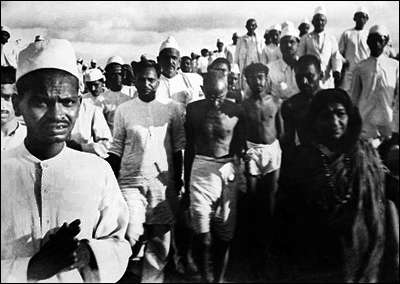

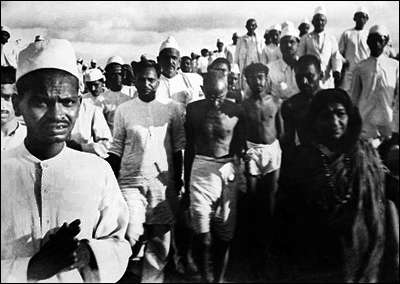

| | + | [[Image:Gandhi Salt March.jpg|thumb|400px|right|[[Gandhi]] during the Salt March (1930)]] |

| | + | '''Civil disobedience''' encompasses the active refusal to obey certain [[law]]s, demands, and commands of a [[government]] or of an occupying power without resorting to physical violence. Based on the position that laws can be unjust, and that there are [[human rights]] that supersede such laws, civil disobedience developed in an effort to achieve [[social change]] when all channels of negotiation failed. The act of civil disobedience involves the breaking of a law, and as such is a [[crime]] and the participants expect and are willing to suffer [[punishment]] in order to make their case known. |

| | + | {{toc}} |

| | + | Civil disobedience has been used successfully in nonviolent resistance movements in [[India]] ([[Mahatma Gandhi]]'s [[social welfare]] campaigns and campaigns to speed up independence from the [[British Empire]]), in [[South Africa]] in the fight against [[apartheid]], and in the [[African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)|American Civil Rights Movement]], among others. Until all people live under conditions in which their human rights are fully met, and there is prosperity and [[happiness]] for all, civil disobedience may be necessary to accomplish those goals. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Deifinition== | + | ==Definition== |

| − | [[Image:Midge potts arrested.jpg|thumb|240px|right|An anti-war activist is arrested for civil disobedience on the steps of the [[Supreme Court of the United States]] on [[February 9]], [[2005]].]] | + | [[Image:Midge potts arrested.jpg|thumb|300px|right|An anti-war activist is arrested for civil disobedience on the steps of the [[Supreme Court of the United States]] on February 9, 2005.]] |

| − | '''Civil disobedience''' encompasses the active refusal to obey certain [[law]]s, demands and commands of a [[government]] or of an occupying [[power (international)|power]] without resorting to physical violence. It could be said that it is [[compassion]] in the form a respectful disagreement. Civil disobedience has been used in [[nonviolent resistance]] movements in [[India]] ([[Mahatma Ghandi|Gandhi's]] social welfare campaigns and campaigns to speed up independence from the British Empire), in [[South Africa]] in the fight against [[apartheid]], and in the [[American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)|American Civil Rights Movement]].

| + | The [[United States|American]] author [[Henry David Thoreau]] pioneered the modern theory behind the practice of '''civil disobedience''' in his 1849 essay, ''Civil Disobedience,'' originally titled ''Resistance to Civil Government''. The driving idea behind the essay was that of self-reliance, and how one is in morally good standing as long as one can "get off another man's back;" so one doesn't have to physically fight the government, but one must not support it or have it support one (if one is against it). This essay has had a wide influence on many later practitioners of civil disobedience. Thoreau explained his reasons for having refused to pay [[tax]]es as an act of [[protest]] against [[slavery]] and against the [[Mexican-American War]]. |

| − | The [[United States|American]] author [[Henry David Thoreau]] pioneered the modern theory behind this practice in his 1849 essay ''[[Civil Disobedience (Thoreau)|Civil Disobedience]]'' ([[wikisource:Civil Disobedience - Henry David Thoreau|Wikisource Text]]), originally titled "Resistance to Civil Government". The driving idea behind the essay was that of self-reliance, and how one is in morally good standing as long as one can "get off another man's back"; so one doesn't have to physically fight the government, but one must not support it or have it support one (if one is against it). This essay has had a wide influence on many later practitioners of civil disobedience. In the essay, Thoreau explained his reasons for having [[tax resistance|refused to pay taxes]] as an act of [[protest]] against [[slavery]] and against the [[Mexican-American War]]. | |

| | | | |

| − | == Theories and techniques of civil disobedience == | + | Civil disobedience can be distinguished from other active forms of protest, such as [[riot]]ing, because of its passivity and non-violence. |

| − | In seeking an active form of civil disobedience, one may choose to deliberately break certain laws, such as by forming a peaceful blockade or occupying a facility illegally. Protesters practice this non-violent form of [[civil disorder]] with the expectation that they will be arrested, or even attacked or beaten by the authorities. Protesters often undergo training in advance on how to react to arrest or to attack, so that they will do so in a manner that quietly or limply resists without threatening the authorities. | + | |

| | + | == Theories and techniques == |

| | + | In seeking an active form of civil disobedience, one may choose to deliberately break certain [[law]]s, such as by forming a peaceful [[blockade]] or occupying a facility illegally. Protesters practice this non-violent form of civil disorder with the expectation that they will be [[arrest]]ed, or even attacked or beaten by the authorities. Protesters often undergo training in advance on how to react to arrest or to attack, so that they will do so in a manner that quietly or limply resists without threatening the authorities. |

| | | | |

| | For example, [[Mahatma Gandhi]] outlined the following rules: | | For example, [[Mahatma Gandhi]] outlined the following rules: |

| − | #A civil resister (or ''[[Satyagraha|satyagrahi]]'') will harbour no anger. | + | #A civil resister (or ''[[Satyagraha|satyagrahi]]'') will harbor no anger |

| − | #He will suffer the anger of the opponent. | + | #He will suffer the anger of the opponent |

| − | #In so doing he will put up with assaults from the opponent, never retaliate; but he will not submit, out of fear of punishment or the like, to any order given in anger. | + | #In so doing he will put up with assaults from the opponent, never retaliate; but he will not submit, out of fear of punishment or the like, to any order given in anger |

| − | #When any person in authority seeks to arrest a civil resister, he will voluntarily submit to the arrest, and he will not resist the attachment or removal of his own property, if any, when it is sought to be confiscated by authorities. | + | #When any person in authority seeks to arrest a civil resister, he will voluntarily submit to the arrest, and he will not resist the attachment or removal of his own property, if any, when it is sought to be confiscated by authorities |

| − | #If a civil resister has any property in his possession as a trustee, he will refuse to surrender it, even though in defending it he might lose his life. He will, however, never retaliate. | + | #If a civil resister has any property in his possession as a trustee, he will refuse to surrender it, even though in defending it he might lose his life. He will, however, never retaliate |

| − | #Retaliation includes swearing and cursing. | + | #Retaliation includes swearing and cursing |

| − | #Therefore a civil resister will never insult his opponent, and therefore also not take part in many of the newly coined cries which are contrary to the spirit of ''[[ahimsa]]''. | + | #Therefore a civil resister will never insult his opponent, and therefore also not take part in many of the newly coined cries which are contrary to the spirit of ''ahimsa'' |

| − | #A civil resister will not [[salute]] the [[Union Jack]], nor will he insult it or officials, English or Indian. | + | #A civil resister will not salute the Union Jack, nor will he insult it or officials, English or Indian |

| − | #In the course of the struggle if anyone insults an official or commits an assault upon him, a civil resister will protect such official or officials from the insult or attack even at the risk of his life. | + | #In the course of the struggle if anyone insults an official or commits an assault upon him, a civil resister will protect such official or officials from the insult or attack even at the risk of his life |

| | | | |

| − | Gandhi distinguished between his idea of ''[[satyagraha]]'' and the [[passive resistance]] of the west. | + | Gandhi distinguished between his idea of ''[[satyagraha]]'' and the [[passive resistance]] of the west. Gandhi's rules were specific to the Indian independence movement, but many of the ideas are used by those practicing civil disobedience around the world. The most general principle on which civil disobedience rests is non-violence and passivity, as protesters refuse to retaliate or take action. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Examples of Civil Disobedience==

| + | The writings of [[Leo Tolstoy]] were influential on Gandhi. Aside from his literature, Tolstoy was famous for advocating [[pacifism]] as a method of social reform. Tolstoy himself was influenced by the Sermon on the Mount, in which [[Jesus]] tells his followers to turn the other cheek when attacked. Tolstoy's philosophy is outlined in his work, ''Kingdom of God is Within You''. |

| − | === Use in independence movements===

| |

| − | Civil disobedience has served as a major tactic of [[nationalism|nationalist]] movements in former [[colony|colonies]] in [[Africa]] and [[Asia]] prior to their gaining [[independence]]. Most notably [[Mahatma Gandhi]] developed civil disobedience as an anti-colonialist tool. Gandhi said "Civil disobedience is the inherent right of a citizen to be civil, implies discipline, thought, care, attention and sacrifice". Gandhi learned of Civil Disobedience from Thoreau's classic essay, which caused Gandhi to adopt a non-violent approach.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===India===

| + | Many who practice civil disobedience do so out of [[religion|religious]] [[faith]], and clergy often participate in or lead actions of civil disobedience. A notable example is [[Philip Berrigan]], a [[Roman Catholic]] priest who was arrested dozens of times in acts of civil disobedience in antiwar protests. |

| | | | |

| − | The first '''[[Satyagraha]]''' revolutions inspired by [[Mahatma Gandhi]] in the [[Indian Independence Movement]] occurred in [[Kheda]] district of [[Gujarat]] and the [[Champaran]] district of [[Bihar]] between the years of 1918 and 1919. | + | ==Philosophy of civil disobedience== |

| | + | The practice of civil disobedience comes into conflict with the [[law]]s of the country in which it takes place. Advocates of civil disobedience must strike a balance between obeying these laws and fighting for their beliefs without creating a society of [[anarchy]]. [[Immanuel Kant]] developed the "categorical imperative" in which every person's action should be just so that it could be taken to be a universal law. In civil disobedience, if every person were to act that way, there is the danger that anarchy would result. |

| | | | |

| − | ====Champaran, Bihar====

| + | Therefore, those practicing civil disobedience do so when no other recourse is available, often regarding the law to be broken as contravening a higher principle, one that falls within the categorical imperative. Knowing that breaking the law is a [[crime|criminal]] act, and therefore that [[punishment]] will ensue, civil disobedience marks the law as unjust and the lawbreaker as willing to suffer in order that justice may ensue for others. |

| − | In Champaran, a district in the then-province, now state of [[Bihar]], tens of thousands of landless serfs, indentured laborers and poor farmers were forced to grow [[indigo]] and other cash crops instead of the food crops necessary for their survival. Suppressed by the ruthless militias of the landlords (mostly British), they were given measly compensation, leaving them mired in extreme poverty. The villages were kept extremely dirty and unhygienic, and [[alcoholism]], [[untouchability]] and [[purdah]] were rampant. Now in the throes of a devastating famine, the British levied an oppressive tax which they insisted on increasing in rate. The situation was desperate.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ====Kheda, Gujarat====

| + | Within the framework of [[democracy]], ideally rule by the people, debate exists over whether or not practices such as civil disobedience are in fact not illegal because they are legitimate expressions of the people's discontent. When the incumbent government breaks the existing [[social contract]], some would argue that citizens are fully justified in rebelling against it as the government is not fulfilling the citizens' needs. Thus, one might consider civil disobedience validated when legislation enacted by the government is in violation of [[natural law]]. |

| − | In [[Kheda]], a district of villages and small towns in [[Gujarat]], the peasants mostly owned their own lands, and were economically better-off than their compatriots in Bihar, although on the whole, the district was plagued by poverty, scant resources, the social evils of alcoholism and [[untouchability]], and overall British indifference and hegemony.

| |

| | | | |

| − | However, a terrible famine had struck the district and a large part of Gujarat, and virtually destroyed the agrarian economy. The poor peasants had barely enough to feed themselves, but the British government of the [[Bombay Presidency]] insisted that the farmers not only pay full taxes, but also pay the 23 percent increase slated to take effect that very year.

| + | The principle of civil disobedience is recognized as justified, even required, under exceptional circumstance such as [[war crime]]s. In the [[Nuremberg Trials]] following [[World War II]], individuals were held accountable for their failure to resist laws that caused extreme [[suffering]] to innocent people. |

| | | | |

| − | Purdah is not a means of supression as metioned here. it is really a mark of dignity and a procalamation that woman is not commodity.

| + | ==Examples of civil disobedience== |

| | + | Civil disobedience in was used to great effect in [[Civil disobedience#India|India]] by [[Gandhi]], in [[Civil disobedience#Poland|Poland]] by the [[Solidarity]] movement against [[Communism]], in [[Civil disobedience#South Africa|South Africa]] against [[apartheid]], and in the [[Civil disobedience#The United States|United States]] by [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] against [[racism]]. It was also used as a major tactic of [[nationalism|nationalist]] movements in former [[colony|colonies]] in [[Africa]] and [[Asia]] prior to their gaining [[independence]]. |

| | | | |

| − | ====Gandhi's solution==== | + | ===India=== |

| − | While many civic groups sent petitions and published editorials, Gandhi proposed ''satyagraha'' - non-violent, mass [[civil disobedience]]. While it was strictly non-violent, Gandhi was proposing real action, a real revolt that the oppressed peoples of India were dying to undertake.

| + | [[Gandhi]] first used his ideas of ''[[Satyagraha]]'' in [[India]] on a local level in 1918, in Champaran, a district in the state of Bihar, and in Kheda in the state of Gujarat. In response to [[poverty]], scant resources, the social evils of [[alcoholism]] and untouchability, and overall British indifference and hegemony, Gandhi proposed ''satyagraha''--non-violent, mass civil disobedience. While it was strictly non-violent, Gandhi was proposing real action, a real revolt that the oppressed peoples of India were dying to undertake. |

| − | | + | [[Image:Gandhi Kheda 1918.jpg|right|thumb|300px|[[Gandhi]] in 1918, when he led the Kheda Satyagraha against allegedly unjust taxation.]] |

| − | Gandhi also insisted that neither the protestors in Bihar nor in Gujarat allude to or try to propagate the concept of ''Swaraj'', or ''Independence''. This was not about political freedom, but a revolt against abject tyranny amidst a terrible humanitarian disaster. While accepting participants and help from other parts of India, Gandhi insisted that no other district or province revolt against the Government, and that the [[Indian National Congress]] not get involved apart from issuing resolutions of support, to prevent the British from giving it cause to use extensive suppressive measures and brand the revolts as treason. | + | Gandhi insisted that the protesters neither allude to or try to propagate the concept of ''Swaraj,'' or ''Independence''. The action was not about political freedom, but a revolt against abject tyranny amidst a terrible humanitarian disaster. While accepting participants and help from other parts of India, Gandhi insisted that no other district or province revolt against the government, and that the [[Indian National Congress]] not get involved apart from issuing resolutions of support, to prevent the British from giving it cause to use extensive suppressive measures and brand the revolts as [[treason]]. |

| − | | |

| − | =====In Champaran=====

| |

| − | Gandhi established an [[ashrama]] in Champaran, organizing scores of his veteran supporters and fresh volunteers from the region. He organized a detailed study and survey of the villages, accounting the atrocities and terrible episodes of suffering, including the general state of degenerate living. Building on the confidence of villagers, he began leading the clean-up of villages, building of schools and hospitals and encouraging the village leadership to undo purdah, untouchability and the suppression of women. He was joined by many young nationalists from the parts and all over India, including [[Brajkishore Prasad]], Dr. [[Rajendra Prasad]] and [[Jawaharlal Nehru]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | But his main assault came as he was arrested by police on the charge of creating unrest and was ordered to leave the province. Hundreds of thousands of people protested and rallied outside the jail, police stations and courts demanding his release, which the court unwillingly did. Gandhi led organized protests and strike against the landlords, who with the guidance of the British government, signed an agreement granting more compensation and control over farming for the poor farmers of the region, and cancellation of revenue hikes and collection until the famine ended. It was during this agitation, that Gandhi was addressed by the people as ''Bapu'' (''Father'') and ''Mahatma'' (''Great Soul'').

| |

| | | | |

| − | =====In Kheda=====

| + | In both states, Gandhi organized civil resistance on the part of tens of thousands of landless farmers and poor farmers with small lands, who were forced to grow [[indigo]] and other cash crops instead of the food crops necessary for their survival. It was an area of extreme poverty, unhygienic villages, rampant alcoholism and untouchables. In addition to the crop-growing restrictions, the British had levied an oppressive [[tax]]. Gandhi’s solution was to establish an [[ashram]] near Kheda, where scores of supporters and volunteers from the region did a detailed study of the villages—itemizing atrocities, suffering, and degenerate living conditions. He led the villagers in a clean up movement, encouraging social reform, and building [[school]]s and [[hospital]]s. |

| − | [[Image:Gandhi Kheda 1918.jpg|right|thumb|200px|[[Gandhi]] in 1918, when he led the Kheda Satyagraha against allegedly unjust taxation.]]

| |

| − | In Gujarat, Gandhi was only the spiritual head of the struggle. His chief lieutenant, [[Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel]] and a close coterie of devoted Gandhians, namely [[Narhari Parikh]], [[Mohanlal Pandya]] and [[Ravi Shankar Vyas]] toured the countryside, organized the villagers and gave them political leadership and direction. Many aroused Gujaratis from the cities of [[Ahmedabad]] and [[Vadodara]] joined the organizers of the revolt, but Gandhi and Patel resisted the involvement of Indians from other provinces, seeking to keep it a purely Gujarati struggle.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Patel and his colleagues organized a major tax revolt, and all the different ethnic and caste communities of Kheda rallied around it. The peasants of Kheda signed a petition calling for the tax for this year to be scrapped in wake of the famine. The government in Bombay rejected the charter. They warned that if the peasants did not pay, the lands and property would be confiscated and many arrested. And once confiscated, they would not be returned even if most complied. None of the villages flinched.

| + | For his efforts, Gandhi was arrested by [[police]] on the charges of unrest and was ordered to leave Bihar. Hundreds of thousands of people protested and rallied outside the [[jail]], police stations, and courts demanding his release, which was unwillingly granted. Gandhi then organized protests and strikes against the landlords, who finally agreed to more pay and allowed the farmers to determine what crops to raise. The government canceled tax collections until the famine ended. |

| | | | |

| − | The tax withheld, the government's collectors and inspectors sent in [[Pathan]] thugs to seize property and cattle, while the police forfeited the lands and all agrarian property. The farmers did not resist arrest, nor retaliate to the force employed with violence. Instead, they used their cash and valuables to donate to the ''Gujarat Sabha'' which was officially organizing the protest.

| + | In Kheda, Gandhi’s associate, [[Sardar Vallabhai Patel]] led the actions, guided by Gandhi's ideas. The revolt was astounding in terms of discipline and unity. Even when all their personal property, land, and livelihood were seized, a vast majority of Kheda's farmers remained firmly united in support of Patel. Gujaratis sympathetic to the revolt in other parts resisted the government machinery, and helped to shelter the relatives and property of the protesting [[peasant]]s. Those Indians who sought to buy the confiscated lands were ostracized from society. Although nationalists like [[Sardul Singh Caveeshar]] called for sympathetic revolts in other parts, Gandhi and Patel firmly rejected the idea. |

| | | | |

| − | The revolt was astounding in terms of discipline and unity. Even when all their personal property, land and livelihood were seized, a vast majority of Kheda's farmers remained firmly united in the support of Patel. Gujaratis sympathetic to the revolt in other parts resisted the government machinery, and helped the shelter the relatives and property of the protesting peasants. Those Indians who sought to buy the confiscated lands were ostracized from society. Although nationalists like [[Sardul Singh Caveeshar]] called for sympathetic revolts in other parts, Gandhi and Patel firmly rejected the idea. | + | The government finally sought to foster an honorable agreement for both parties. The tax for the year in question and the next would be suspended, and the increase in rate reduced, while all confiscated property would be returned. The success in these situations spread throughout the country. |

| | | | |

| − | The Government finally sought to foster an honorable agreement for both parties. The tax for the year in question, and the next would be suspended, and the increase in rate reduced, while all confiscated property would be returned.

| + | Gandhi used Satyagraha on a national level in 1919, the year the [[Rowlatt Act]] was passed, allowing the government to imprison persons accused of sedition without trial. Also that year, in Punjab, 1-2,000 people were wounded and 400 or more were killed by British troops in the ''[[Amritsar massacre]]''.<ref>[https://www.mkgandhi.org/bio5000/bio5index.htm Gandhi's Life in 5000 words] From the book ''Mahatma Gandhi - His Life in pictures''. Retrieved May 28, 2021.</ref> A traumatized and angry nation engaged in retaliatory acts of violence against the British. Gandhi criticized both the British and the Indians. Arguing that all violence was evil and could not be justified, he convinced the national party to pass a resolution offering condolences to British victims and condemning the Indian riots.<ref> Rajmohan Gandhi, ''Patel: A Life'' (Navjivan Trust, 2011, ISBN 978-8172291389).</ref> At the same time, these incidents led Gandhi to focus on complete self-government and complete control of all government institutions. This matured into ''Swaraj,'' or complete individual, spiritual, political independence. |

| − | | |

| − | Gujaratis also worked in cohesion to return the confiscated lands to their rightful owners. The ones who had bought the lands seized were influenced to return them, even though the British had officially said it would stand by the buyers.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Success and legacy====

| |

| − | | |

| − | Gandhi's resulting fame spread like fire all over the nation. He had become a defining influence on [[Indian Nationalism]]. People in Gujarat still revere Gandhi and [[Sardar Patel]], and their role in the freedom struggle. [[Gujarat]] is the most industrialized and progressive state in [[India]] today. In [[Bihar]], poverty and social conflict pervades what was the founding of the Satyagraha movement. The [[Naxalite]] insurgency is centered around the same age-old problem of class struggle between poor farmers and rich landlords, now involving [[terrorism]].

| |

| | | | |

| | + | The first move in the ''Swaraj'' non-violent campaign was the famous [[Salt March]]. The government monopolized the [[salt]] trade, making it illegal for anyone else to produce it, even though it was readily available to those near the sea coast. Because the tax on salt affected everyone, it was a good focal point for protest. Gandhi marched 400 kilometers (248 miles) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat, to make his own salt near the sea. In the 23 days (March 12 to April 6) it took, the march gathered thousands. Once in Dandi, Gandhi encouraged everyone to make and trade salt. In the next days and weeks, thousands made or bought illegal salt, and by the end of the month, more than 60,000 had been arrested. It was one of his most successful campaigns. Although Gandhi himself strictly adhered to non-violence throughout his life, even [[fasting]] until violence ceased, his dream of a unified, independent India was not achieved and his own life was taken by an assassin. Nevertheless, his ideals have lived on, inspiring those in many other countries to use non-violent civil disobedience against oppressive and unjust governments. |

| | | | |

| | ===Poland=== | | ===Poland=== |

| − | {{Main|Solidarity}}

| + | [[Image:Poleglych Stoczniowcow.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Monument to Shipyard Workers Fallen in 1970, created following the [[Gdańsk Agreement]], and unveiled December 16, 1980.]] |

| − | | |

| − | Civil disobedience was a tactic used by the [[Poland|Polish]] in offense to the former communist government.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | In the 1970s and 1980s, the initial success of ''Solidarity'' in particular, and of [[dissident]] movements in general, was fed by a deepening crisis within Soviet-style societies brought about by declining morale, worsening economic conditions (a [[shortage economy]]), and the growing stresses of the [[Cold War]].<ref name = "Int Soc"> {{cite web

| |

| − | |title = The rise of Solidarnosc

| |

| − | |author = Colin Barker

| |

| − | |authorlink = Colin Barker

| |

| − | |work = International Socialism, Issue: 108

| |

| − | |url = http://www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=136&issue=108

| |

| − | |accessdate = 2006-07-10

| |

| − | }} </ref>After a brief period of economic boom, from 1975 the policies of the Polish government, led by Party First Secretary [[Edward Gierek]], precipitated a slide into increasing depression, as [[foreign debt]] mounted.<ref name="Lepak-100">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | last = Lepak

| |

| − | | first = Keith John

| |

| − | | title = Prelude to Solidarity

| |

| − | | publisher = Columbia University Press

| |

| − | | year = 1989

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-231-06608-2

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=YQRcqE5Kht4C&pg=PA100&lpg=PA100&dsig=9NOnsdesZ-I1sxQ8c4LtLYlsh4A p. 100]

| |

| − | }} </ref> In June 1976, the first workers' strikes took place, involving violent incidents at factories in [[Radom]] and [[Ursus (district in Warsaw)|Ursus]].<ref name="Falk-34">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | author = Barbara J. Falk

| |

| − | | title = The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe: Citizen Intellectuals and Philosopher Kings

| |

| − | | publisher = Central European University Press

| |

| − | | year = 2003

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 963-9241-39-3

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=ZsR0CGdWCC0C&pg=PA34&lpg=PA34&sig=trvZ7qPN4WlIdUsqqvs_wVHP4T0 p.34]

| |

| − | }} </ref> When these incidents were quelled by the government, the worker's movement received support from [[intelligentsia|intellectual dissidents]], many of them associated with the [[Workers' Defence Committee|Committee for Defense of the Workers]] ({{lang-pl|Komitet Obrony Robotników}}, abbreviated ''KOR''), formed in 1976.<ref name = "Int Soc"/><ref name=Falk-35">Falk, op.cit., [http://books.google.com/books?id=ZsR0CGdWCC0C&pg=PA35&lpg=PA34&sig=gR89xv6t5I02RBj29BhTldMBpXo Google Print, p.35] </ref> The following year, ''KOR'' was renamed the [[Committee for Social Self-defence]] (''KSS-KOR'').

| |

| − | | |

| − | On [[October 16]], [[1978]], the [[Bishop of Kraków]], [[Karol Wojtyła]], was elected [[Pope John Paul II]]. A year later, during his first pilgrimage to Poland, his masses were attended by millions of his countrymen. The Pope called for the respecting of [[nation]]al and [[religion|religious]] traditions and advocated for freedom and human rights, while denouncing violence. To many Poles, he represented a spiritual and moral force that could be set against brute material forces; he was a [[bellwether]] of change, and became an important symbol—and supporter—of changes to come.<ref name="Weigel-Pope">

| |

| − | {{cite book

| |

| − | | last = Weigel

| |

| − | | first = George

| |

| − | | authorlink = George Weigel

| |

| − | | coauthors =

| |

| − | | editor =

| |

| − | | others =

| |

| − | | title = The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism

| |

| − | | origdate =

| |

| − | | origyear =

| |

| − | | origmonth =

| |

| − | | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=6kFfjei_XCEC&pg=PA136&lpg=PA136&sig=CuKF-pVRfgLmpUxq_o8Wava9ouY

| |

| − | | format = ebook

| |

| − | | accessdate = 2006-07-10

| |

| − | | edition =

| |

| − | | year = 2003

| |

| − | | month = May

| |

| − | | publisher = Oxford University Press US

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-19-516664-7

| |

| − | | pages = p. 136

| |

| − | }}</ref><ref name="Weigel-Witness">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | first = George

| |

| − | | last = Weigel

| |

| − | | authorlink = George Weigel

| |

| − | | title =Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul II

| |

| − | | publisher = HarperCollins

| |

| − | | year = 2005

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-06-073203-2

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?&id=-mzOGzb2T2UC&pg=PA292&lpg=PA292&sig=dh-4ur6H-RVsIWEl8oAk5TwvTsQ p. 292]

| |

| − | }} </ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Early strikes (1980–81)====

| |

| − | Strikes did not occur merely due to problems that had emerged shortly before the labor unrest, but due to governmental and economic difficulties spanning more than a decade. In July 1980, [[Edward Gierek]]'s government, facing economic crisis, decided to raise prices while slowing the growth of wages. At once there ensued a wave of strikes and factory occupations.<ref name = "Int Soc"/> Although the strike movement had no coordinating center, the workers had developed an information network to spread news of their struggle. A "dissident" group, the Committee for the Defense of the Workers (''KOR''), which had originally been set up in 1976 to organize aid for victimized workers, attracted small groups of working-class militants in major industrial centers.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> At the [[Lenin Shipyard]] in [[Gdańsk]], the firing of [[Anna Walentynowicz]], a popular crane operator and activist, galvanized the outraged workers into action.<ref name = "Int Soc" /><ref name="BBC-80">{{cite web

| |

| − | | title=The birth of Solidarity (1980)

| |

| − | | work=BBC News

| |

| − | | url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/special_report/1999/09/99/iron_curtain/timelines/poland_80.stm

| |

| − | | accessdate=2006-07-10

| |

| − | }}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | On August 14, the shipyard workers began their strike, organized by the [[Free Trade Unions of the Coast]] (''Wolne Związki Zawodowe Wybrzeża'').<ref name="B&S">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | author = Michael Bernhard

| |

| − | | coauthor = Henryk Szlajfer

| |

| − | | title = From The Polish Underground

| |

| − | | publisher = Penn State Press

| |

| − | | year = 2004

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=nUhiPCkawCoC&pg=PA405&lpg=PA405&sig=CzMr6IlR2B-Q1rZ_vmbDXdM-6wk p. 405]

| |

| − | }} </ref> The workers were led by electrician [[Lech Wałęsa]], a former shipyard worker who had been dismissed in 1976, and who arrived at the shipyard late in the morning of August 14.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> The strike committee demanded the rehiring of Walentynowicz and Wałęsa, as well as the according of respect to workers' rights and other social concerns. In addition, they called for the raising of a [[Monument to fallen Shipyard Workers|monument to the shipyard workers]] who had been killed in 1970 and for the legalization of independent trade unions.<ref name="Perdue-39">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | author = William D Perdue,

| |

| − | | title = Paradox of Change: The Rise and Fall of Solidarity in the New Poland

| |

| − | | publisher = Praeger/Greenwood,

| |

| − | | year = 1995

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-275-95295-9,

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?d=6WnLe3_hhgUC&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39&sig=qC29FZhY_jznp29dptxpdtXjPLs p.39]

| |

| − | }}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Image:Strike Gdansk 1980.jpg|thumb|left|200px|1980 strike at [[Gdańsk Shipyard]], birthplace of [[Solidarity]].]]

| |

| − | The Polish government enforced censorship, and official media said little about the "sporadic labor disturbances in Gdańsk"; as a further precaution, all phone connections between the coast and the rest of Poland were soon cut.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> Nonetheless, the government failed to contain the information: a spreading wave of ''[[samizdat]]''s ([[Polish language|Polish]]: ''bibuła''),<ref name="bibula">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | author = Michael H. Bernhard

| |

| − | | title = The Origins of Democratization in Poland

| |

| − | | publisher = Columbia University Press

| |

| − | | year = 1993

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-231-08093-X

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=TF_DXcqeMBEC&pg=PA149&lpg=PA149&sig=kErUdt1a52vlaL2-AePTOtDfbo4 p. 149]

| |

| − | }} </ref> including ''[[Robotnik (1983-1990)|Robotnik]]'' (The Worker), and [[Grapevine (gossip)|grapevine gossip]], along with [[Radio Free Europe]] broadcasts that penetrated the [[Iron Curtain]],<ref name="RFE">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | author = G. R. Urban

| |

| − | | title = Radio Free Europe and the Pursuit of Democracy: My War Within the Cold War

| |

| − | | publisher = Yale University Press

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-300-06921-9

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=a4BFvTBOT6oC&pg=PA147&lpg=PA147&sig=ZS9gAMrvOUHPMJpfTP-d4-yUv54 p. 147]

| |

| − | }}</ref> ensured that the ideas of the emerging Solidarity movement quickly spread.

| |

| − | | |

| − | On August 16, delegations from other strike committees arrived at the shipyard.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> Delegates ([[Bogdan Lis]], [[Andrzej Gwiazda]] and others) together with shipyard strikers agreed to create an [[Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee]] (''Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy'', or ''MKS'').<ref name = "Int Soc" /> On August 17 a priest, [[Henryk Jankowski]], performed a mass outside the shipyard's gate, at which [[21 demands of MKS|21 demands of the ''MKS'']] were put forward. The list went beyond purely local matters, beginning with a demand for new, independent trade unions and going on to call for a relaxation of the [[censorship]], a right to strike, new rights for the Church, the freeing of political prisoners, and improvements in the national health service.<ref name = "Int Soc" />

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Image:Lechu.JPG|thumb|right|200px|[[Lech Wałęsa]] (left) with [[Mieczysław Jagielski]] (1980).]]

| |

| − | Next day, a delegation of ''KOR'' [[intelligentsia]], including [[Tadeusz Mazowiecki]], arrived to offer their assistance with negotiations. A ''[[bibuła]]'' news-sheet, ''Solidarność'', produced on the shipyard’s [[printing press]] with ''KOR'' assistance, reached a daily print run of 30,000 copies.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> Meanwhile, [[Jacek Kaczmarski]]'s [[protest song]], ''[[Mury (song)|Mury]]'' (''Walls''), gained popularity with the workers.<ref name="Kaczmarski"> [http://www.warsawvoice.pl/view/9158/ Yalta 2.0], [[Warsaw Voice]], 31 August 2005, last accessed on 8 October 2006.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | On August 18, the [[Szczecin Shipyard]] joined the strike, under the leadership of [[Marian Jurczyk]]. A tidal wave of strikes swept the coast, closing ports and bringing the economy to a halt. With ''KOR'' assistance and support from many intellectuals, workers occupying factories, mines and shipyards across Poland joined forces. Within days, over 200 factories and enterprises had joined the strike committee.<ref name = "Int Soc" /><ref name="BBC-80"/> By August 21, most of Poland was affected by the strikes, from coastal shipyards to the mines of the [[Upper Silesian Industrial Area]]. More and more new unions were formed, and joined the federation.

| |

| − | [[Image:Poleglych Stoczniowcow.jpg|left|thumb|200px|Monument to Shipyard Workers Fallen in 1970, created following the [[Gdańsk Agreement]], and unveiled [[December 16]], [[1980]].]] | |

| − | Thanks to popular support within Poland, as well as to international support and media coverage, the Gdańsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. On August 21 a Governmental Commission (''Komisja Rządowa'') including [[Mieczysław Jagielski]] arrived in Gdańsk, and another one with [[Kazimierz Barcikowski]] was dispatched to Szczecin. On August 30 and 31, and on September 3, representatives of the workers and the government signed an agreement ratifying many of the workers' demands, including the right to strike.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> This agreement came to be known as the August or [[Gdańsk agreement]] (''Porozumienia sierpniowe'').<ref name="BBC-80"/> Though concerned with labor-union matters, the agreement enabled citizens to introduce democratic changes within the communist political structure and was regarded as a first step toward dismantling the [[PZPR|Party's]] monopoly of power.<ref name="Davies">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | last = Davies

| |

| − | | first = Norman

| |

| − | | authorlink = Norman Davies

| |

| − | | title = [[God's Playground]]

| |

| − | | year = 2005

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-231-12819-3

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=EBpghdZeIwAC&pg=PA483&lpg=PA483&sig=8z6yTa2wvwLje4ZDT481E0jk00k p. 483]

| |

| − | }} </ref> The workers' main concerns were the establishment of a labor union independent of communist-party control, and recognition of a legal right to strike. Workers’ needs would now receive clear representation.<ref name="Seleny-100">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | first = Anna

| |

| − | | last = Seleny

| |

| − | | title = The Political Economy of State-Society Relations in Hungary and Poland

| |

| − | | publisher = Cambridge University Press

| |

| − | | year = 2006

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-521-83564-X

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=i89VOJzIuOAC&pg=RA1-PA100&lpg=RA1-PA100&sig=YDunSm2HPSYExZm1oPJgZshaEe8 p.100]

| |

| − | }} </ref> Another consequence of the Gdańsk Agreement was the replacement, in September 1980, of Edward Gierek by [[Stanisław Kania]] as Party First Secretary.<ref name="Seleny-115">Anna Seleny, op.cit., [http://books.google.com/books?id=i89VOJzIuOAC&pg=RA7-PP1&lpg=RA7-PP1&sig=EkhruwtJ0yh3j9vj-9-BLaN_3g0 Google Print, p.115]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Encouraged by the success of the August strikes, on September 17 workers' representatives, including Lech Wałęsa, formed a nationwide labor union, Solidarity (''Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy (NSZZ) "Solidarność"'').<ref name = "Int Soc"/><ref name="BBC-80"/><ref name="WIEM"> [http://portalwiedzy.onet.pl/12313,,,,solidarnosc_nszz,haslo.html Solidarność NSZZ] in [[WIEM Encyklopedia]]. Last accessed on 10 October 2006 {{pl icon}} </ref> It was the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country.<ref name=EB>''[http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9068595/Solidarity Solidarity]'', [[Encyclopedia Britannica]].</ref> Its name was suggested by [[Karol Modzelewski]], and its famous [[Solidarity logo|logo]] was conceived by [[Jerzy Janiszewski]], designer of many Solidarity-related posters. The new union's supreme powers were vested in a [[legislature|legislative body]], the Convention of Delegates (''Zjazd Delegatów''). The [[executive]] branch was the National Coordinating Commission (''Krajowa Komisja Porozumiewawcza''), later renamed the National Commission (''Komisja Krajowa''). The Union had a regional structure, comprising 38 regions (''region'') and two districts (''okręg'').<ref name="WIEM"/> On [[December 16]], [[1980]], the [[Monument to fallen Shipyard Workers|Monument to Fallen Shipyard Workers]] was unveiled. On [[January 15]], [[1981]], a Solidarity delegation, including Lech Wałęsa, met in [[Rome]] with [[Pope John Paul II]]. From September 5 to 10, and from September 26 to October 7, Solidarity's first national congress was held, and Lech Wałęsa was elected its president.<ref name="Kalendarium"> [http://www.solidarity25.pap.pl/kalendarium-NSZZ-pl.pdf KALENDARIUM NSZZ „SOLIDARNOŚĆ” 1980-1989]. {{pdf}} Last accessed on 15 October 2006 {{pl icon}} </ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Meanwhile Solidarity had been transforming itself from a trade union into a social movement<ref name="Misztal">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | first = Bronisław

| |

| − | | last = Misztal

| |

| − | | title = Poland after Solidarity: Social Movements Vs. the State

| |

| − | | publisher = Transaction Publishers

| |

| − | | year = 1985

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-88738-049-2

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=5yeK_1TXSVwC&pg=PA4&lpg=PA4&sig=vvchTYv5G5zcq7y9GsT4weN67A8 p.4]

| |

| − | }}</ref> or more specifically, a [[revolutionary movement]].<ref name="Goodwin">[[Jeff Goodwin]], ''No Other Way Out: States and Revolutionary Movements, 1945-1991''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Chapter 1 and 8.</ref> Over the 500 days following the Gdańsk Agreement, 9-10 million workers, intellectuals and students joined it or its suborganizations,<ref name = "Int Soc" /> such as the [[Independent Students Union|Independent Student Union]] (''Niezależne Zrzeszenie Studentów'', created in September 1980), the Independent Farmers' Trade Union (''NSZZ Rolników Indywidualnych "Solidarność"'', created in May 1981) and the Independent Craftsmen's Trade Union.<ref name="WIEM"/> It was the only time in recorded history that a quarter of a country's population (some 80% of the total Polish work force) had voluntarily joined a single organization.<ref name = "Int Soc"/><ref name="WIEM"/> ''"History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom,"'' the Solidarity program stated a year later. ''"What we had in mind was not only bread, butter and sausages, but also justice, democracy, truth, legality, human dignity, freedom of convictions, and the repair of the republic."''<ref name="BBC-80"/>

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Image:WieczorWroclawia20marca1981.jpg|thumb|350px|right|March 20-21, 1981, issue of ''Wieczór Wrocławia'' (The [[Wrocław]] Evening). Blank spaces remain after the government [[censor]] has pulled articles from page 1 (''right'', "What happened at [[Bydgoszcz]]?") and from the last page (''left'', "Country-wide strike alert"), leaving only their titles. The printers—[[Solidarity trade union|Solidarity-trade-union]] members—have decided to run the newspaper as is, with blank spaces intact. The bottom of page 1 of this [[master (original)|master]] copy bears the hand-written Solidarity confirmation of that decision.]]

| |

| − | Using strikes and other protest actions, Solidarity sought to force a change in government policies. At the same time, it was careful never to use force or violence, so as to avoid giving the government any excuse to bring security forces into play.<ref name="Wehr">

| |

| − | {{cite book

| |

| − | | last =

| |

| − | | first =

| |

| − | | authorlink =

| |

| − | | coauthors =

| |

| − | | editor = Paul Wehr, Guy Burgess, Heidi Burgess

| |

| − | | others =

| |

| − | | title = Justice Without Violence

| |

| − | | origdate =

| |

| − | | origyear =

| |

| − | | origmonth =

| |

| − | | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=o8ipY9HVHmcC&lpg=PA29&pg=PA28&sig=ot7HF0E-YXDJQ8_zMpuVSuvl8Ig

| |

| − | | format = ebook

| |

| − | | accessdate = 2006-07-06

| |

| − | | edition =

| |

| − | | year = 1994

| |

| − | | month = Feb

| |

| − | | publisher = Lynne Rienner Publishers

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 1-55587-491-6

| |

| − | | pages = p 28

| |

| − | }}</ref><ref name="O'K">

| |

| − | {{cite book

| |

| − | | last = Cavanaugh-O'Keefe

| |

| − | | first = John

| |

| − | | authorlink =

| |

| − | | coauthors =

| |

| − | | editor =

| |

| − | | others =

| |

| − | | title = Emmanuel, Solidarity: God's Act, Our Response

| |

| − | | origdate =

| |

| − | | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=_P9owylILP4C&pg=PA68&lpg=PA68&sig=a531pYBFmXgNUIeXQ-PguOVwrts

| |

| − | | format = ebook

| |

| − | | accessdate = 2006-07-06

| |

| − | | edition =

| |

| − | | date =

| |

| − | | year = 2001

| |

| − | | month = Jan

| |

| − | | publisher = Xlibris Corporation

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-7388-3864-0

| |

| − | | pages = p 68

| |

| − | }}</ref> After 27 [[Bydgoszcz]] Solidarity members, including [[Jan Rulewski]], [[Bydgoszcz events|were beaten up]] on March 19, a 4-hour strike on March 27, involving over half a million people, paralyzed the country.<ref name = "Int Soc"/> This was the largest strike in the history of the [[Eastern bloc]],<ref name="MacEachin">

| |

| − | {{cite book

| |

| − | | last = MacEachin

| |

| − | | first = Douglas J

| |

| − | | authorlink =

| |

| − | | coauthors =

| |

| − | | editor =

| |

| − | | others =

| |

| − | | title = U.S. Intelligence and the Confrontation in Poland, 1980-1981

| |

| − | | origdate =

| |

| − | | origyear =

| |

| − | | origmonth =

| |

| − | | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=93eUER87BmsC&pg=PA120&lpg=PA120&sig=2PGSLWEZSI4RfSpZpR5EJv3IcnM

| |

| − | | format = ebook

| |

| − | | accessdate = 2006-07-10

| |

| − | | edition =

| |

| − | | year = 2004

| |

| − | | month = Aug

| |

| − | | publisher = Penn State Press

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-271-02528-X

| |

| − | | pages = p 120

| |

| − | }}</ref> and it forced the government to promise an investigation into the beatings.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> This concession, and Wałęsa's agreement to defer further strikes, proved a setback to the movement, as the euphoria that had swept Polish society subsided.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> Nonetheless the Polish communist party—the [[Polish United Workers Party|Polish United Workers' Party]] (''PZPR'')—had lost its total control over society.<ref name="Davies"/>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Yet while Solidarity was ready to take up negotiations with the government,<ref name="BBC-81">

| |

| − | {{cite web

| |

| − | | title = Martial law (1981)

| |

| − | | work = BBC News

| |

| − | | url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/special_report/1999/09/99/iron_curtain/timelines/poland_81.stm

| |

| − | | accessdate = 2006-07-10

| |

| − | }}</ref> the [[Polish communists]] were unsure what to do, as they issued empty declarations and bid their time.<ref name="Seleny-115"/> Against the background of a deteriorating communist shortage economy and unwillingness to negotiate seriously with Solidarity, it became increasingly clear that the Communist government would eventually have to suppress the Solidarity movement as the only way out of the impasse, or face a truly revolutionary situation. The atmosphere was increasingly tense, with various local chapters conducting a growing number of uncoordinated strikes in response to the worsening economic situation.<ref name = "Int Soc" />On December 3 Solidarity announced that a 24-hour strike would be held if the government were granted additional powers to suppress dissent, and that a general strike would be declared if those powers were used.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ====Martial law (1981–83)==== | + | Civil disobedience was a tactic used by the [[Poland|Polish]] in protest of the former communist government. In the 1970s and 1980s, there occurred a deepening crisis within Soviet-style societies brought about by declining morale, worsening economic conditions (a [[shortage economy]]), and the growing stresses of the [[Cold War]].<ref name = "Int Soc">Colin Barker, [http://isj.org.uk/the-rise-of-solidarnosc/ The rise of Solidarnosc] ''International Socialism'', October 17, 2005. Retrieved May 4, 2021.</ref> After a brief period of economic boom, from 1975, the policies of the Polish government, led by Party First Secretary [[Edward Gierek]], precipitated a slide into increasing [[depression (economics)|depression]], as [[foreign debt]] mounted.<ref>Keith John Lepak, ''Prelude to Solidarity'' (Columbia University Press, 1989, ISBN 0231066082).</ref> In June 1976, the first workers' [[strike]]s took place, involving violent incidents at factories in [[Radom]] and [[Ursus]].<ref>Barbara J. Falk, ''The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe: Citizen Intellectuals and Philosopher Kings'' (Central European University Press, 2003, ISBN 9639241393).</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | After the [[Gdańsk Agreement]], the Polish government was under increasing pressure from the [[Soviet Union]] to take action and strengthen its position. [[Stanisław Kania]] was viewed by Moscow as too independent, and on [[October 18]], [[1981]], the Party Central Committee put him in the minority. Kania lost his post as First Secretary, and was replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. [[Wojciech Jaruzelski]], who adopted a strong-arm policy.<ref name="BBC-81"/>

| + | On October 16, 1978, the [[Bishop of Kraków]], [[Karol Wojtyła]], was elected [[Pope John Paul II]]. A year later, during his first pilgrimage to Poland, his masses were attended by millions of his countrymen. The Pope called for the respecting of [[nation]]al and [[religion|religious]] traditions and advocated for freedom and human rights, while denouncing violence. To many Poles, he represented a spiritual and moral force that could be set against brute material forces; he was a [[bellwether]] of change, and became an important symbol—and supporter—of changes to come. He was later to define the concept of "solidarity" in his Encyclical ''Sollicitudo Rei Socialis'' (December 30, 1987).<ref>George Weigel, ''The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism'' (Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0195166647).</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | On [[December 13]], [[1981]], Jaruzelski began a crack-down on Solidarity, declaring [[martial law in Poland|martial law]] and creating a [[Military Council of National Salvation]] (''Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego'', or ''WRON''). Solidarity's leaders, gathered at [[Gdańsk]], were arrested and isolated in facilities guarded by the Security Service (''[[Służba Bezpieczeństwa]]'' or ''SB''), and some 5,000 Solidarity supporters were arrested in the middle of the night.<ref name = "Int Soc"/><ref name="WIEM"/> Censorship was expanded, and military forces appeared on the streets.<ref name="BBC-81"/> A couple of hundred strikes and occupations occurred, chiefly at the largest plants and at several [[Silesia]]n coal mines, but were broken by [[ZOMO]] paramilitary [[riot police]]. One of the largest demonstrations, on [[December 16]], [[1981]], took place at the [[Wujek Coal Mine]], where government forces opened fire on demonstrators, killing 9<ref name = "Int Soc" /> and seriously injuring 22.<ref name="Kalendarium"/> Next day, during protests at [[Gdańsk]], government forces again fired at demonstrators, killing 1 and injuring 2. By [[December 28]], [[1981]], strikes had ceased, and Solidarity appeared crippled. On [[October 8]], [[1982]], the organization was delegalized and banned.<ref name="Perdue"> | + | On July of 1980, the government of Edward Gierek, facing an economic crisis, decided to raise the [[prices]] while slowing the growth of the [[wages]]. A wave of strikes and factory occupations began at once.<ref name = "Int Soc"/> At the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, workers were outraged at the sacking of Anna Walentynowicz, a popular crane operator and well-known activist who became a spark that pushed them into action.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/special_report/1999/09/99/iron_curtain/timelines/poland_80.stm The birth of Solidarity] ''BBC News''. Retrieved May 28, 2021.</ref> The workers were led by electrician [[Lech Wałęsa]], a former shipyard worker who had been dismissed in 1976, and who arrived at the shipyard on August 14.<ref name = "Int Soc" /> The strike committee demanded rehiring of Anna Walentynowicz and Lech Wałęsa, raising [[Monument to fallen Shipyard Workers|a monument to the casualties of 1970]], respecting of worker's rights and additional social demands. |

| − | {{cite book

| |

| − | | last = Perdue

| |

| − | | first = William D

| |

| − | | authorlink =

| |

| − | | coauthors =

| |

| − | | editor =

| |

| − | | others =

| |

| − | | title = Paradox of Change: The Rise and Fall of Solidarity in the New Poland

| |

| − | | origdate =

| |

| − | | origyear =

| |

| − | | origmonth =

| |

| − | | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=6WnLe3_hhgUC&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&sig=wPq4m12vM31b5dJzGDPJkc-Yne0

| |

| − | | format = ebook

| |

| − | | accessdate = 2006-07-10

| |

| − | | edition =

| |

| − | | year = 1995

| |

| − | | month = Oct

| |

| − | | publisher = Praeger/Greenwood

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-275-95295-9

| |

| − | | pages = p 9

| |

| − | }}</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| | + | By August 21, most of Poland was affected by the strikes, from coastal shipyards to the mines of the [[Upper Silesian Industrial Area]]. Thanks to popular support within Poland, as well as to international support and media coverage, the Gdańsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. Though concerned with [[labor union]] matters, the Gdańsk agreement enabled citizens to introduce democratic changes within the communist political structure and was regarded as a first step toward dismantling the Party's monopoly of power.<ref>Norman Davies, ''God's Playground: A History of Poland, Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795'' (Columbia University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0231128179).</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | The [[international community]] outside the [[Iron Curtain]] condemned Jaruzelski's actions and declared support for Solidarity.<ref name="WIEM"/> [[US President]] [[Ronald Reagan]] imposed [[economic sanctions]] on Poland, which eventually would force the Polish government into liberalizing its policies.<ref name="Neier">

| + | Buoyed by the success of the strike, on the September 17, the representatives of Polish workers, including Lech Wałęsa, formed a nationwide trade union, Solidarity (''Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy'' "''Solidarność''"). On December 16, 1980, the Monument to fallen Shipyard Workers was unveiled. On January 15, 1981, a delegation from Solidarity, including Lech Wałęsa, met [[Pope John Paul II]] in Rome. Between September 5 and 10 and September 26 to October 7, the first national congress of Solidarity was held, and Lech Wałęsa was elected its president. |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | author = Aryeh Neier

| |

| − | | title = Taking Liberties: Four Decades in the Struggle for Rights

| |

| − | | publisher = Public Affairs

| |

| − | | year = 2003

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 1-891620-82-7

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=Z5_hgLHYUiwC&pg=PA251&lpg=PA251&sig=4wxxUWdD8jgieONsxFO8tDcJPKU p. 251]

| |

| − | }} </ref> Meanwhile the [[CIA]]<ref name="Schweizer">

| |

| − | {{cite book

| |

| − | | last = Schweizer

| |

| − | | first = Peter

| |

| − | | authorlink = Peter Schweizer

| |

| − | | coauthors =

| |

| − | | editor =

| |

| − | | others =

| |

| − | | title = Victory: The Reagan Administration's Secret Strategy That Hastened the Collapse of the Soviet...

| |

| − | | origdate =

| |

| − | | origyear =

| |

| − | | origmonth =

| |

| − | | url = http://books.google.com/books?ie=UTF-8&vid=ISBN0871136333&id=rfia4MnyOykC&dq=Solidarity+Poland+left&lpg=PA85&pg=PA86&sig=9MUPgcK3WOQgL1iS9DZQL503Fy8

| |

| − | | format = ebook

| |

| − | | accessdate = 2006-07-10

| |

| − | | edition =

| |

| − | | year = 1996

| |

| − | | month = May

| |

| − | | publisher = Atlantic Monthly Press

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-87113-633-3

| |

| − | | pages = p 86

| |

| − | }}</ref> together with the Catholic Church and various Western trade unions such as the [[AFL-CIO]] provided funds, equipment and advice to the Solidarity underground.<ref name="Hannaford">

| |

| − | {{ cite book |

| |

| − | | author = Peter D. Hannaford

| |

| − | | title = Remembering Reagan

| |

| − | | publisher = Regnery Publishing

| |

| − | | year = 2000

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-89526-514-1

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=8HJf1be87bgC&pg=PA70&lpg=PA70&sig=HVl-NLDpy1bBNMUn6PNz0wzV-Hw p. 170], [http://books.google.com/books?id=8HJf1be87bgC&pg=PA71&lpg=PA70&sig=CJijLi-Efn41LmokPWGpWhQoR8Q p. 171]

| |

| − | }} </ref> The political alliance of Reagan and the Pope would prove important to the future of Solidarity.<ref name="Hannaford"/> The Polish public also supported what was left of Solidarity; a major medium for demonstrating support of Solidarity became masses held by priests such as [[Jerzy Popiełuszko]].<ref name="Auer">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | author = Stefan Auer

| |

| − | | authorlink = Stefan Auer

| |

| − | | title = Liberal Nationalism in Central Europe

| |

| − | | publisher = Routledge

| |

| − | | year = 2004

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-415-31479-8

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=b2IRot3UaQ0C&pg=PA70&lpg=PA70&sig=F2UH_aPJWyTSiUNT2UNLGPcTbqg p. 70]

| |

| − | }} </ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | In July 1983, martial Law was formally lifted, though many heightened controls on civil liberties and political life, as well as food rationing, remained in place through the mid- to late 1980s.<ref name="HSE">

| |

| − | {{ cite book

| |

| − | | author = Gary Clyde Hufbauer

| |

| − | | coauthors = Jeffrey J. Schott , Kimberly Ann Elliott

| |

| − | | title = Economic Sanctions Reconsidered: History and Current Policy

| |

| − | | publisher = Institute for International Economics

| |

| − | | year = 1990

| |

| − | | id = ISBN 0-88132-136-2

| |

| − | | pages = [http://books.google.com/books?id=bBJ9LgZ58vYC&pg=PA193&lpg=PA193&sig=JBaZ5_US3HyRwwseXQpH7JMyS2k p. 193]

| |

| − | }} </ref>

| |

| | | | |

| | + | In the meantime Solidarity transformed from a trade union into a [[social movement]]. Over the next 500 days following the Gdańsk Agreement, 9 to 10 million workers, intellectuals, and students joined it or its sub-organizations. It was the first and only recorded time in the history that a quarter of a country's population have voluntarily joined a single organization. "History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom," the Solidarity program stated a year later. "What we had in mind were not only bread, butter, and sausage but also justice, democracy, truth, legality, human dignity, freedom of convictions, and the repair of the republic." |

| | | | |

| | + | Using [[strike]]s and other [[protest action]]s, Solidarity sought to force a change in the governmental policies. At the same time it was careful to never use force or violence, to avoid giving the government any excuse to bring the security forces into play. Solidarity's influence led to the intensification and spread of anti-communist ideals and movements throughout the countries of the Eastern Bloc, weakening their communist governments. In 1983, Lech Wałęsa received the [[Nobel Prize]] for Peace, but the Polish government refused to issue him a passport and allow him to leave the country. Finally, Roundtable Talks between the weakened Polish government and Solidarity-led opposition led to semi-free elections in 1989. By the end of August, a Solidarity-led coalition government was formed, and in December, [[Lech Wałęsa]] was elected president. |

| | | | |

| | ===South Africa=== | | ===South Africa=== |

| − | Both Archbishop [[Desmond Tutu]] and [[Steve Biko]] advocated civil disobedience. The result can be seen in such notable events as the 1989 [[Purple Rain Protest|Purple Rain Revolt]], and the [[Cape Town Peace March]] which defied apartheid laws. | + | Both Archbishop [[Desmond Tutu]] and [[Steve Biko]] advocated civil disobedience in the fight against [[apartheid]]. The result can be seen in such notable events as the 1989 [[Civil disobedience#Purple Rain Protest|Purple Rain Protest]], and the [[Civil disobedience#Cape Town Peace March|Cape Town Peace March]], which defied apartheid laws. |

| | | | |

| − | ====Purple Rain Protest==== | + | ====Purple rain protest==== |

| | + | On September 2, 1989, four days before [[South Africa]]'s racially segregated parliament held its elections, a police water cannon with purple dye was turned on thousands of [[Mass Democratic Movement]] supporters who poured into the city in an attempt to march on South Africa's Parliament on Burg Street in [[Cape Town]]. Protesters were warned to disperse but instead knelt in the street and the water cannon was turned on them. Some remained kneeling while others fled. Some had their feet knocked out from under them by the force of the jet. A group of about 50 protesters streaming with purple dye, ran from Burg Street, down to the parade. They were followed by another group of clergymen and others who were stopped in Plein Street. Some were then arrested. A lone protester, Philip Ivey, redirected the water cannon toward the local headquarters of the ruling National Party. The headquarters, along with the historic, white-painted Old Town House, overlooking Greenmarket Square, were doused with purple dye.<ref> [https://sthp.saha.org.za/memorial/articles/the_day_the_purple_governed.htm The Day the Purple Governed] ''Sunday Times Heritage Project''. Retrieved May 28, 2021.</ref> |

| | | | |

| | + | On the Parade, a large contingent of police arrested everyone they could find who had purple dye on them. When they were booed by the crowd, police dispersed them. About 250 people marching under a banner stating, "The People Shall Govern," dispersed at the intersection of Darling Street and Sir Lowry Road after being stopped by police.<ref> Scott Kract, [https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-09-03-mn-2412-story.html 500 Arrested During Protest in Cape Town] ''Los Angeles Times'', September 3, 1989. Retrieved May 28, 2021.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | On September 2, 1989, four days before [[South Africa]]'s racially segregated parliament held its elections, Burg Street in [[Cape Town]] ran '''purple'''. A police water cannon with purple dye was turned on thousands of [[Mass Democratic Movement]] supporters who poured into the city in an attempt to march on South Africa's Parliament. Office blocks off Greenmarket Square were sprayed purple four stories high as a protester leapt onto the roof of the water cannon vehicle, seized the nozzle and attempted to turn the jet away from the crowds. <ref> Weekend Argus, "Purple Rain halts city demo", front page, Saturday, September 2, 1989</ref> | + | ====Cape Town peace march==== |

| | + | On September 12, 1989, 30,000 [[Cape Town|Capetonians]] marched in support of peace and the end of [[apartheid]]. The event lead by Mayor [[Gordon Oliver]], [[Desmond Tutu|Archbishop Tutu]], Rev [[Frank Chikane]], [[Moulana Faried Esack]], and other religious leaders was held in defiance of the government's ban on political marches. The demonstration forced President [[de Klerk]] to relinquish the hardline against transformation, and the eventual unbanning of the [[African National Congress|ANC]], and other political parties, and the release of [[Nelson Mandela]] less than six months later. |

| | | | |

| − | The historic Town House, a national monument, was sprayed purple and the force of the jet smashed windows in the Central Methodist Church. | + | === The United States === |

| | + | There is a long history of civil disobedience in the [[United States]]. One of the first practitioners was [[Henry David Thoreau]] whose 1849 essay, ''Civil Disobedience,'' is considered a defining exposition of the modern form of this type of action. It advocates the idea that people should not support any government attempting unjust actions. Thoreau was motivated by his opposition to the institution of [[slavery]] and the fighting of the [[Mexican-American War]]. Those participating in the movement for women's [[suffrage]] also engaged in civil disobedience.<ref> [https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/woman-suffrage Woman Suffrage and the 19th Amendment] The National Archives. Retrieved May 28, 2021.</ref> The labor movement in the early twentieth century used sit-in strikes at plants and other forms of civil disobedience. Civil disobedience has also been used by those wishing to protest the [[Vietnam War]], [[apartheid]] in [[South Africa]], and against American intervention in [[Central America.]]<ref>[https://actupny.org/documents/CDdocuments/HistoryNV.html History of Mass Nonviolent Action] ''Civil Disobedience Training''. Retrieved May 28, 2021.</ref> |

| | | | |

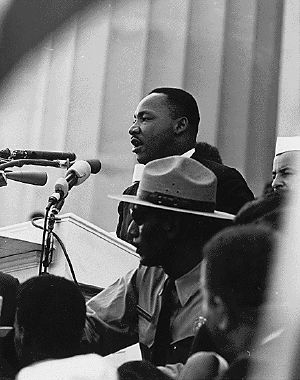

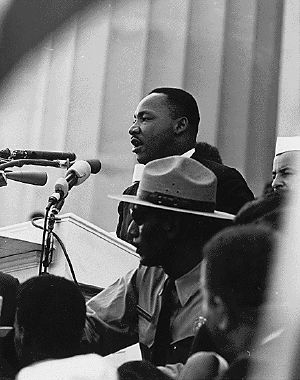

| − | [[Teargas]] was fired and the crowd that had knelt defiantly in the purple jet fled. Adderley Street was closed to traffic as scores of shops and businesses closed their doors and hundreds of people were arrested, including Dr Allan Boesak, UCT academic Dr Charles Villa-Vincencia, Western Cape Council of Churches official Rev. Pierre van den Heever and lawyer Essa Moosa. | + | [[Image:Martin Luther King - March on Washington.jpg|thumb|right|300px|King is perhaps most famous for his "[[I Have a Dream]]" speech, given in front of the [[Lincoln Memorial]] during the 1963 [[March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom]].]] |

| | + | [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] is one of the most famous activists who used civil disobedience to achieve reform. In 1953, at the age of twenty-four, King became pastor of the [[Dexter Avenue Baptist Church]], in [[Montgomery]], [[Alabama]]. King correctly recognized that organized, nonviolent protest against the racist system of southern segregation known as [[Jim Crow laws]] would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Indeed, journalistic accounts and [[television|televised]] footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that made the [[African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)|Civil Rights Movement]] the single most important issue in American politics in the early-1960s. King organized and led marches for blacks' right to [[Voting|vote]], [[desegregation]], [[labor rights]], and other basic civil rights. Most of these rights were successfully enacted into [[Law of the United States|United States law]] with the passage of the [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]] and the [[Voting Rights Act of 1965]]. |

| | | | |

| | + | On December 1, 1955, [[Rosa Parks]] was arrested for refusing to comply with the [[Jim Crow laws|Jim Crow law]] that required her to give up her seat to a white man. The [[Montgomery Bus Boycott]], led by King, soon followed. The boycott lasted for 382 days, the situation becoming so tense that King's house was bombed. King was arrested during this campaign, which ended with a [[Supreme Court of the United States|United States Supreme Court]] decision outlawing [[racial segregation]] on all public transport. |

| | | | |

| − | Journalists including Brenton Geach (''Weekend Argus''), Rehana Rousouw (''South'') and Gaye Davis (''Weekly Mail'') were held.

| + | King was instrumental in the founding of the [[Southern Christian Leadership Conference]] (SCLC) in 1957, a group created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. King continued to dominate the organization. King was an adherent of the philosophies of nonviolent civil disobedience used successfully in [[India]] by [[Mahatma Gandhi]], and he applied this philosophy to the protests organized by the SCLC. |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Protesters were warned to disperse but instead knelt in the street and the water cannon was turned on them. Some remained kneeling while others fled. Some had their feet knocked out from under them by the force of the jet. In Adderley Street, shoppers ran for cover, their eyes streaming, and a young couple with a baby in a pram were hurriedly ushered into a shop which then locked its doors. A group of about 50 protesters streaming with purple dye, ran from Burg Street, down to the parade. They were followed by another group of clergymen and others who were stopped in Plein Street. Some were then arrested. On the Parade, a large contingent of policemen arrested everyone they could find who had purple dye on them. When they were booed by the crowd, police dispersed them. About 250 people marching under a banner stating "The People Shall Govern" dispersed at the intersection of Darling Street and Sir Lowry Road after being stopped by police. <ref> Weekend Argus, "Purple Rain halts city demo", front page, Saturday, September 2, 1989</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Cape Town Peace March====

| |

| − | On September 12, 1989, 30 000 [[Cape Town|Capetonians]] marched in support of peace and the end of [[apartheid]]. The event lead by Mayor [[Gordon Oliver]], [[Desmond Tutu|Archbishop Tutu]], Rev [[Frank Chikane]], [[Moulana Faried Esack]] and other religious leaders was held in defiance of the government's ban on political marches. The demonstration forced President [[de Klerk]] to relinquish the hardline against transformation, and the eventual unbanning of the [[African National Congress|ANC]], and other political parties, and the release of [[Nelson Mandela]] less than six months later.

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Civil disobedience in the United States ===

| |

| − | {{Main|Martin Luther King, Jr.}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Martin Luther King, Jr.|Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.]], a leader of the US civil rights movement in the [[United States]] in the 1960s also adopted civil disobedience techniques, and [[pacifism|antiwar]] activists both during and after the [[Vietnam War]] have done likewise. Since the 1970s, pro-life or anti-abortion groups have practiced civil disobedience against the U.S. government over the issue of legalized [[abortion]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 1953, at the age of twenty-four, King became pastor of the [[Dexter Avenue Baptist Church]], in [[Montgomery, Alabama]]. On December 1, 1955, [[Rosa Parks]] was arrested for refusing to comply with the [[Jim Crow laws|Jim Crow law]] that required her to give up her seat to a white man. The [[Montgomery Bus Boycott]], led by King, soon followed. (This, despite the fact that in March of the same year, a 15 year old school girl, Claudette Colvin, suffered the same fate but King refused to become involved, instead preferring to focus on leading his church.<ref>Scott-King, Correta, ''My life with Martin Luther King Jr.'' (New York, 1969) p.124-5</ref>) The boycott lasted for 382 days, the situation becoming so tense that King's house was bombed. King was arrested during this campaign, which ended with a [[Supreme Court of the United States|United States Supreme Court]] decision outlawing [[racial segregation]] on all public transport.

| |

| − | | |

| − | King was instrumental in the founding of the [[Southern Christian Leadership Conference]] (SCLC) in 1957, a group created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. King continued to dominate the organization. King was an adherent of the philosophies of nonviolent [[civil disobedience]] used successfully in [[India]] by [[Mahatma Gandhi]], and he applied this philosophy to the protests [[Community organizing|organize]]d by the SCLC. | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The FBI began [[wiretapping]] King in 1961, fearing that communists were trying to infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement, but when no such evidence emerged, the bureau used the incidental details caught on tape over six years in attempts to force King out of the pre-eminent leadership position.

| |

| − | | |

| − | King correctly recognized that organized, nonviolent protest against the racist system of southern segregation known as [[Jim Crow laws]] would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Indeed, journalistic accounts and [[television|televised]] footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that made the [[Civil rights|Civil Rights Movement]] the single most important issue in American politics in the early-1960s.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | King organized and led marches for blacks' right to [[Voting|vote]], [[desegregation]], [[labor rights]] and other basic civil rights. Most of these rights were successfully enacted into [[Law of the United States|United States law]] with the passage of the [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]] and the [[Voting Rights Act of 1965]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | King and the SCLC applied the principles of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out in often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities. Sometimes these confrontations turned violent. King and the SCLC were instrumental in the unsuccessful protest movement in [[Albany, Georgia|Albany]], in 1961 & 1962, where divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts; in the [[Birmingham, Alabama|Birmingham]] protests in the summer of 1963; and in the protest in [[St. Augustine, Florida]], in 1964. King and the SCLC joined forces with SNCC in [[Selma, Alabama]], in December 1964, where SNCC had been working on voter registration for a number of months.

| |

| − | <ref>

| |

| − | {{cite news

| |

| − | | last = Haley