Difference between revisions of "Cholesterol" - New World Encyclopedia

Katya Swarts (talk | contribs) (Added article and credit tags) |

m ({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Contracted}} | ||

<!-- Here is a table of data; skip past it to edit the text. —> | <!-- Here is a table of data; skip past it to edit the text. —> | ||

{| class="toccolours" border="1" style="float: right; clear: right; margin: 0 0 1em 1em; border-collapse: collapse;" | {| class="toccolours" border="1" style="float: right; clear: right; margin: 0 0 1em 1em; border-collapse: collapse;" | ||

Revision as of 14:37, 14 August 2006

| Cholesterol | |

|---|---|

| |

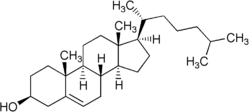

| Chemical name | 10,13-dimethyl-17- (6-methylheptan-2-yl)- 2,3,4,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17- dodecahydro-1H- cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-3-ol |

| Chemical formula | C27H46O |

| Molecular mass | 386.65 g/mol |

| CAS number | [57-88-5] |

| Melting point | 146-147 °C |

| SMILES | C[C@H]3C4[C@](CC[C@@H]4 [C@H](C)CCCC(C)C)([H])[C@]2 ([H])CC=C1C[C@@H](O)CC[C@]1 (C)[C@@]2([H])C3 |

| Disclaimer and references | |

Cholesterol is a sterol (a combination steroid and alcohol) and a lipid found in the cell membranes of all body tissues, and transported in the blood plasma of all animals. Lesser amounts of cholesterol are also found in plant membranes. The name originates from the Greek chole- (bile) and stereos (solid), and the chemical suffix -ol for an alcohol, as researchers first identified cholesterol (C27H45OH) in solid form in gallstones in 1784.

Most cholesterol is not dietary in origin; it is synthesized internally. Cholesterol is present in higher concentrations in tissues which either produce more or have more densely-packed membranes, for example, the liver, spinal cord and brain, and also in atheroma. Cholesterol plays a central role in many biochemical processes, but is best known for the association of cardiovascular disease with various lipoprotein cholesterol transport patterns and high levels of cholesterol in the blood.

Often, when most doctors talk to their patients about the health concerns of cholesterol, they are referring to "bad cholesterol", or low-density lipoprotein (LDL). "Good cholesterol" is high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

Physiology

Function

Cholesterol is required to build and maintain cell membranes; it makes the membrane's fluidity - degree of viscosity - stable over wider temperature intervals (the hydroxyl group on cholesterol interacts with the phosphate head of the membrane, and the bulky steroid and the hydrocarbon chain is embedded in the membrane). Some research indicates that cholesterol may act as an antioxidant.[1] Cholesterol also aids in the manufacture of bile (which helps digest fats), and is also important for the metabolism of fat soluble vitamins, including vitamins A, D, E and K. It is the major precursor for the synthesis of vitamin D, of the various steroid hormones, including cortisol and aldosterone in the adrenal glands, and of the sex hormones progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone. Further recent researchTemplate:Citationneeded shows that cholesterol has an important role for the brain synapses as well as in the immune system, including protecting against cancer.

Recently, cholesterol has also been implicated in cell signalling processes, where it has been suggested that it forms lipid rafts in the plasma membrane. It also reduces the permeability of the plasma membrane to proton and sodium ions.[2]

Synthesis and intake

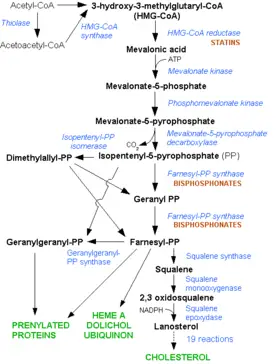

Cholesterol is primarily synthesized from acetyl CoA through the HMG-CoA reductase pathway in many cells and tissues. About 20–25% of total daily production (~1 g/day) occurs in the liver; other sites of higher synthesis rates include the intestines, adrenal glands and reproductive organs. For a person of about 150 pounds (68 kg), typical total body content is about 35 g, typical daily internal production is about 1 g and typical daily dietary intake is 200 to 300 mg. Of the 1,200 to 1,300 mg input to the intestines (via bile production and food intake), about 50% is reabsorbed into the bloodstream.[citation needed]

Konrad Bloch and Feodor Lynen shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1964 for their discoveries concerning the mechanism and regulation of the cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism.

Regulation

Biosynthesis of cholesterol is directly regulated by the cholesterol levels present, though the homeostatic mechanisms involved are only partly understood. A higher intake from food leads to a net decrease in endogenous production, while lower intake from food has the opposite effect. The main regulatory mechanism is the sensing of intracellular cholesterol in the endoplasmic reticulum by the protein SREBP (Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein 1 and 2). In the presence of cholesterol, SREBP is bound to two other proteins: SCAP (SREBP-cleavage activating protein) and Insig1. When cholesterol levels fall, Insig-1 dissociates from the SREBP-SCAP complex, allowing the complex to migrate to the Golgi apparatus, where SREBP is cleaved by S1P and S2P (site 1/2 protease), two enzymes that are activated by SCAP when cholesterol levels are low. The cleaved SREBP then migrates to the nucleus and acts as a transcription factor to bind to the SRE (sterol regulatory element) of a number of genes to stimulate their transcription. Among the genes transcribed are the LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase. The former scavenges circulating LDL from the bloodstream, whereas HMG-CoA reductase leads to an increase of endogenous production of cholesterol.[3] An excess of cholesterol in the bloodstream may lead to its accumulation in the walls of arteries. This build up is what can lead to clogged arteries and eventually to heart attacks and strokes.

A large part of this mechanism was clarified by Dr Michael S. Brown and Dr Joseph L. Goldstein in the 1970s. They received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work in 1985.[3]

The average amount of blood cholesterol varies with age, typically rising gradually until one is about 60 years old. There appear to be seasonal variations in cholesterol levels in humans, more, on average, in winter.[4]

Excretion

Cholesterol is excreted from the liver in bile and reabsorbed from the intestines. Under certain circumstances, when more concentrated, as in the gallbladder, it crystallises and is the major constituent of most gallstones, although lecithin and bilirubin gallstones also occur less frequently.

Body fluids

Cholesterol is minimally soluble in water; it cannot dissolve and travel in the water-based bloodstream. Instead, it is transported in the bloodstream by lipoproteins - protein "molecular-suitcases" that are water-soluble and carry cholesterol and triglycerides internally. The apoproteins forming the surface of the given lipoprotein particle determine from what cells cholesterol will be removed and to where it will be supplied.

The largest lipoproteins, which primarily transport fats from the intestinal mucosa to the liver, are called chylomicrons. They carry mostly fats in the form of triglycerides and cholesterol. In the liver, chylomicron particles release triglycerides and some cholesterol, and are converted into low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, which carry triglycerides and cholesterol on to other body cells. In healthy individuals the LDL particles are large and relatively few in number. In contrast, large numbers of small dense LDL (sdLDL) particles are strongly associated with promoting atheromatous disease within the arteries. For this reason, LDL is referred to as "bad cholesterol".

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles transport cholesterol back to the liver for excretion, but vary considerably in their effectiveness for doing this. Having large numbers of large HDL particles correlates with better health outcomes, and hence it is commonly called "good cholesterol". In contrast, having small amounts of large HDL particles is independently associated with atheromatous disease progression within the arteries.

Clinical significance

Hypercholesterolemia

- Main article: Hypercholesterolemia

In conditions with elevated concentrations of oxidized LDL particles, especially small LDL particles, cholesterol promotes atheroma formation in the walls of arteries, a condition known as atherosclerosis, which is the principal cause of coronary heart disease and other forms of cardiovascular disease. In contrast, HDL particles (especially large HDL) have been the only identified mechanism by which cholesterol can be removed from atheroma. Increased concentrations of HDL correlate with lower rates of atheroma progressions and even regression.

Of the lipoprotein fractions, LDL, IDL and VLDL are regarded as atherogenic (prone to cause atherosclerosis). Levels of these fractions, rather than the total cholesterol level, correlate with the extent and progress of atherosclerosis. Conversely, the total cholesterol can be within normal limits, yet be made up primarily of small LDL and small HDL particles, under which conditions atheroma growth rates would still be high. In contrast, however, if LDL particle number is low (mostly large particles) and a large percentage of the HDL particles are large, then atheroma growth rates are usually low, even negative, for any given total cholesterol concentration.Template:Citationneeded

These effects are further complicated by the relative concentration of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) in the endothelium, since ADMA down-regulates production of nitric oxide, a relaxant of the endothelium. Thus, high levels of ADMA, associated with high oxidized levels of LDL pose a heightened risk factor for cardiovascular disease.Template:Citationneeded

Multiple human trials utilizing HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors or statins, have repeatedly confirmed that changing lipoprotein transport patterns from unhealthy to healthier patterns significantly lower cardiovascular disease event rates, even for people with cholesterol values currently considered low for adults; however, no statistically significant mortality benefit has been derived to date by lowering cholesterol using medications in asymptomatic people, i.e., no heart disease, no history of heart attack, etc.

Some of the better-designed recent randomized human outcome trials studying patients with coronary artery disease or its risk equivalents include the Heart Protection Study (HPS), the PROVE-IT trial, and the TNT trial. In addition, there are trials that have looked at the effect of lowering LDL as well as raising HDL and atheroma burden using intravascular ultrasound. Small trials have shown prevention of progression of coronary artery disease and possibly a slight reduction in atheroma burden with successful treatment of an abnormal lipid profile.

The American Heart Association provides a set of guidelines for total (fasting) blood cholesterol levels and risk for heart disease:[5]

| Level mg/dL | Level mmol/L | Interpretation |

| <200 | <5.2 | Desirable level corresponding to lower risk for heart disease |

| 200-239 | 5.2-6.2 | Borderline high risk |

| >240 | >6.2 | High risk |

However, as today's testing methods determine LDL ("bad") and HDL ("good") cholesterol separately, this simplistic view has become somewhat outdated. The desirable LDL level is considered to be less than 100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L), although a newer target of <70 mg/dL can be considered in higher risk individuals based on some of the above-mentioned trials. A ratio of total cholesterol to HDL —another useful measure— of far less than 5:1 is thought to be healthier. Of note, typical LDL values for children before fatty streaks begin to develop is 35 mg/dL.

Patients should be aware that most testing methods for LDL do not actually measure LDL in their blood, much less particle size. For cost reasons, LDL values have long been estimated using the Friedewald formula: [total cholesterol] − [total HDL] − 20% of the triglyceride value = estimated LDL. The basis of this is that Total cholesterol is defined as the sum of HDL, LDL, and VLDL. Ordinarily just the Total, HDL, and Triglycerides are actually measured. The VLDL is estimated as one-fifth of the Triglycerides. It is important to fast for at least 8-12 hours before the blood test because the triglyceride level varies significantly with food intake.

Increasing clinical evidenceTemplate:Citationneeded has strongly supported the greater predictive value of more-sophisticated testing that directly measures both LDL and HDL particle concentrations and size, as opposed to the more usual estimates/measures of the total cholesterol carried within LDL particles or the total HDL concentration.

Hypocholesterolemia

Abnormally low levels of cholesterol are termed hypocholesterolemia. Research into the causes of this state is relatively limited, and while some studies suggest a link with depression, cancer and cerebral hemorrhage it is unclear whether the low cholesterol levels are a cause for these conditions or an epiphenomenon[1].

Cholesterol in plants

Many sources (including textbooks) incorrectly assert that there is no cholesterol in plants. This misperception is made worse in the United States, where FDA rules allow for cholesterol quantities less than 2 mg/serving to be ignored in labelling. While plants sources contain much less cholesterol (Behrman and Gopalan suggest 50mg/kg of total lipids, as opposed to 5g/kg in animals), they still contain the substance, and require it to construct membranes.[6]

Cholesteric liquid crystals

Some cholesterol derivatives, (among others simple cholesteric lipids) are known to generate liquid crystalline phase called cholesteric. The cholesteric phase is in fact a chiral nematic phase, and changes colour when its temperature changes. Therefore, cholesterol derivatives are commonly used as temperature-sensitive dyes, in liquid crystal thermometers, and in temperature-sensitive paints.

See also

- Triglycerides

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Smith LL. Another cholesterol hypothesis: cholesterol as antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med 1991;11:47-61. PMID 1937129.

- ↑ Haines, TH. Do sterols reduce proton and sodium leaks through lipid bilayers? Prog Lipid Res 2001:40:299–324. PMID 11412894.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Anderson RG. Joe Goldstein and Mike Brown: from cholesterol homeostasis to new paradigms in membrane biology. Trends Cell Biol 2003:13:534-9. PMID 14507481.

- ↑ Ockene IS, Chiriboga DE, Stanek EJ 3rd, Harmatz MG, Nicolosi R, Saperia G, Well AD, Freedson P, Merriam PA, Reed G, Ma Y, Matthews CE, Hebert JR. Seasonal variation in serum cholesterol levels: treatment implications and possible mechanisms. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:863-70. PMID 15111372.

- ↑ "About cholesterol" - American Heart Association

- ↑ Behrman EJ, Gopalan Venkat. Cholesterol and plants. J Chem Educ 2005;82:1791-1793. PDF

External links

- Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults US National Institutes of Health Adult Treatment Panel III

- Aspects of fat digestion and metabolism - UN/WHO Report 1994

- American Heart Association - "About Cholesterol"

- Cholesterol in Plants

- HowStuffWorks

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.