Difference between revisions of "Biblical Criticism" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→History) |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

'''Biblical criticism''' is a form of [[historical criticism]] that seeks to analyze the [[Bible]] through asking certain questions about the text, such as who wrote it, when it was written, for whom was it written, why was it written, what was the historical and cultural setting of the text, how well preserved is the original text, how unified is the text, what sources were used by the author, how was the text transmitted over time, what is the text's literary genre, and how did it come to be accepted as part of the Bible? | '''Biblical criticism''' is a form of [[historical criticism]] that seeks to analyze the [[Bible]] through asking certain questions about the text, such as who wrote it, when it was written, for whom was it written, why was it written, what was the historical and cultural setting of the text, how well preserved is the original text, how unified is the text, what sources were used by the author, how was the text transmitted over time, what is the text's literary genre, and how did it come to be accepted as part of the Bible? | ||

| − | Biblical criticism has been traditionally divided into [[textual criticism]]—also called [[lower criticism]]—which seeks to establish the original text out of the variant readings of [[biblical manuscript|ancient manuscripts]] | + | Biblical criticism has been traditionally divided into [[textual criticism]]—also called [[lower criticism]]—which seeks to establish the original text out of the variant readings of [[biblical manuscript|ancient manuscripts]]; and [[higher criticism]], which focuses on identifying the author, date, sources, and place of writing for each book of the [[Bible]]. In the twentieth-century a number of specific critical methodologies have been developed to address such questions in greater depth. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | While biblical criticism generally treats the Bible as a human book rather than simply accepting it as the inspired Word of God, the tools of biblical criticism today are used both by skeptics and believers alike to better understand the scriptures and how they relate to people's spiritual lives. | ||

| + | ==History== | ||

| + | Although questions about the sources and manuscripts of the Bible date back to ancient rabbinical and patristic times, the Renaissance humanism and the Protestant Reformation laid the foundations for its expansion in modern times. The scientific revolution changed basic assumptions about how truth is perceived, emphasizes reason and experience over faith and the tradition; and the Reformation opened the way for individuals to interpret the scriptures with the final authority for the proper interpretation being one's own conscience rather than church hierarchies. In the nineteenth century the rapid growth in the study of ancient languages. Old Testament scholars such as [[Jean Astruc]], [[J.G. Eichhorn]] and [[Julius Wellhausen]] proposed dramatic new theories about the sources and editing of the [[Pentateuch]]; and [[New Testament]] experts such as [[Adolf von Harnack]] proposed bold new theories about the historical significance of [[New Testament]] texts. In the twentieth century, theologians such as [[Rudolf Bultmann]] initiated [[form criticism]], and archaeological discoveries such as the [[Dead Sea Scrolls]] and the [[Nag Hammadi library]] revolutionized biblical criticism. | ||

==Lower criticism== | ==Lower criticism== | ||

| Line 24: | Line 25: | ||

==Higher criticism== | ==Higher criticism== | ||

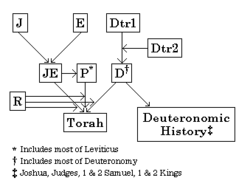

| − | [[Image:Modern documentary hypothesis.png|thumb|Diagram of the Documentary hypothesis shows the relationships among the various supposed sources of the Pentateuch.]] | + | [[Image:Modern documentary hypothesis.png|thumb|left|250px|Diagram of the Documentary hypothesis shows the relationships among the various supposed sources of the Pentateuch.]] |

Higher criticism is a name given to critical studies of the Bible that treat it as a text created by human beings at a particular historical time and for various human motives, in contrast with the treatment of the Bible as the [[Biblical inerrancy|inerrant]] word of [[God]]. Higher criticism thus studies the biblical text as it would study any other ancient text, in order to discover its cultural context, audience, purpose, influences, and ultimately its meaning. | Higher criticism is a name given to critical studies of the Bible that treat it as a text created by human beings at a particular historical time and for various human motives, in contrast with the treatment of the Bible as the [[Biblical inerrancy|inerrant]] word of [[God]]. Higher criticism thus studies the biblical text as it would study any other ancient text, in order to discover its cultural context, audience, purpose, influences, and ultimately its meaning. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 35: | ||

==Types of Biblical criticism== | ==Types of Biblical criticism== | ||

| + | Biblical criticism has spawned many subdivisions other than the broad categories of higher and lower criticism, textual criticism and source criticism, as well as using techniques found in the literary criticism generally. Some of these subdivisions are: | ||

| + | * [[Form criticism]]—a means of analyzing the typical features of texts, especially their conventional forms or structures, in order to relate them to their sociological contexts | ||

| + | * [[Redaction criticism]]—focusing on how the editor or redactor has shaped and molded the narrative to express his theological goals | ||

| + | * Historical criticism—investigating the origins of a text, often used interchangeably with [[source criticism]] | ||

| + | * [[Rhetorical criticism]]—studying how arguments have been built to drive home a certain point the author or speaker intended to make. | ||

| + | * [[Narrative criticism]]—analyzing the stories a speaker or a writer tells to understand how they help us make meaning out of our daily human experiences | ||

| + | * [[Tradition history]]—studies biblical literature in terms of the process by which traditions passed from stage to stage into their final form, especially how they passed from oral tradition to written form | ||

| + | * [[Psychological criticism]]—analyzing the psychological and cultural effects of biblical traditions on their audiences, past and present | ||

| + | * [[Linguistic criticism]]—a branch of textual criticism focusing on biblical languages, especially [[Koine Greek]] and [[Hebrew]], and [[Aramaic]], among others | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

;Further reading | ;Further reading | ||

* {{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| Line 158: | Line 146: | ||

* Shinan, Avigdir, and Yair Zakovitch (2004). ''That's Not What the Good Book Says'', Miskal-Yediot Ahronot Books and Chemed Books, Tel-Aviv | * Shinan, Avigdir, and Yair Zakovitch (2004). ''That's Not What the Good Book Says'', Miskal-Yediot Ahronot Books and Chemed Books, Tel-Aviv | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 22:27, 6 November 2007

Biblical criticism is a form of historical criticism that seeks to analyze the Bible through asking certain questions about the text, such as who wrote it, when it was written, for whom was it written, why was it written, what was the historical and cultural setting of the text, how well preserved is the original text, how unified is the text, what sources were used by the author, how was the text transmitted over time, what is the text's literary genre, and how did it come to be accepted as part of the Bible?

Biblical criticism has been traditionally divided into textual criticism—also called lower criticism—which seeks to establish the original text out of the variant readings of ancient manuscripts; and higher criticism, which focuses on identifying the author, date, sources, and place of writing for each book of the Bible. In the twentieth-century a number of specific critical methodologies have been developed to address such questions in greater depth.

While biblical criticism generally treats the Bible as a human book rather than simply accepting it as the inspired Word of God, the tools of biblical criticism today are used both by skeptics and believers alike to better understand the scriptures and how they relate to people's spiritual lives.

History

Although questions about the sources and manuscripts of the Bible date back to ancient rabbinical and patristic times, the Renaissance humanism and the Protestant Reformation laid the foundations for its expansion in modern times. The scientific revolution changed basic assumptions about how truth is perceived, emphasizes reason and experience over faith and the tradition; and the Reformation opened the way for individuals to interpret the scriptures with the final authority for the proper interpretation being one's own conscience rather than church hierarchies. In the nineteenth century the rapid growth in the study of ancient languages. Old Testament scholars such as Jean Astruc, J.G. Eichhorn and Julius Wellhausen proposed dramatic new theories about the sources and editing of the Pentateuch; and New Testament experts such as Adolf von Harnack proposed bold new theories about the historical significance of New Testament texts. In the twentieth century, theologians such as Rudolf Bultmann initiated form criticism, and archaeological discoveries such as the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi library revolutionized biblical criticism.

Lower criticism

The so-called lower criticism is a branch of philology or bibliography that is concerned with the identification and removal of errors from texts and manuscripts. No original biblical texts exist today. What we have are copies of the original documents, with several generations of copyists intervening in most cases. Lower criticism was developed in an attempt to find out what the original text actually said.

When an error consists of something being left out, it is called a deletion. When something was added, it is called an interpolation. Biblical critics attempt to recognize interpolations by differences of style, theology, vocabulary, etc., from the main source. When more than one ancient manuscript exists, they can also compare the manuscripts, sometimes discovering verses that have been added, deleted, or changed.

Examples of lower criticism include comparing versions of the text of the Book of Isaiah in the Septuagint Greek version, the Hebrew Masoretic text, and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

New Testament examples include comparisons of various ancient text of the Gospels and epistles, with probable later additions including:

- The ending of [[Gospel of Mark}Mark]], see Mark 16

- Jesus sweating blood in Luke (Luke 22:43-44)

- The of the woman taken in adultery in the John (7:53–8:11)

- the ending of John, see John 21.

- an explicit reference to the Trinity in 1 John, the Comma Johanneum.

Higher criticism

Higher criticism is a name given to critical studies of the Bible that treat it as a text created by human beings at a particular historical time and for various human motives, in contrast with the treatment of the Bible as the inerrant word of God. Higher criticism thus studies the biblical text as it would study any other ancient text, in order to discover its cultural context, audience, purpose, influences, and ultimately its meaning.

The phrase "the higher criticism" became popular in Europe from the mid-eighteenth century to the early twentieth century, to describe the work of such scholars as Jean Astruc, Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1752-1827), Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792-1860), and Julius Wellhausen (1844-1918).

Source criticism is one form of higher criticism, in which scholars seek to understand the components of the current texts, as well as what factors influenced their development. Just as they might see the influence of Christopher Marlowe or an Italian poet on one of Shakespeare's plays, so scholars have identified Canaanite or Babylonian influences on some of the Psalms and creations stories of the Old Testament, and have developed various theories about the relationships of the Gospels to one another, among many other topics.

Two primary examples of source criticism are the Documentary Hypothesis in Old Testament studies and the theory of the existence of the Q Document in New Testament studies. The Documentary hypothesis, also known as the Graf-Wellhausen theory, holds that the Pentateuch, or first five books of the Hebrew Bible, are not the work of Moses as traditionally claimed, but come from several later sources which were combined into their current form during the seventh century B.C.E. The Q Document was posited by New Testament scholars to explain the relations among the Synoptic Gospels, with the most common theory being that Mark was written first, with both Matthew and Luke us a saying source, called "Q" to expand Mark's basic narrative.

Types of Biblical criticism

Biblical criticism has spawned many subdivisions other than the broad categories of higher and lower criticism, textual criticism and source criticism, as well as using techniques found in the literary criticism generally. Some of these subdivisions are:

- Form criticism—a means of analyzing the typical features of texts, especially their conventional forms or structures, in order to relate them to their sociological contexts

- Redaction criticism—focusing on how the editor or redactor has shaped and molded the narrative to express his theological goals

- Historical criticism—investigating the origins of a text, often used interchangeably with source criticism

- Rhetorical criticism—studying how arguments have been built to drive home a certain point the author or speaker intended to make.

- Narrative criticism—analyzing the stories a speaker or a writer tells to understand how they help us make meaning out of our daily human experiences

- Tradition history—studies biblical literature in terms of the process by which traditions passed from stage to stage into their final form, especially how they passed from oral tradition to written form

- Psychological criticism—analyzing the psychological and cultural effects of biblical traditions on their audiences, past and present

- Linguistic criticism—a branch of textual criticism focusing on biblical languages, especially Koine Greek and Hebrew, and Aramaic, among others

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Further reading

- Barton, John (1984). Reading the Old Testament: Method in Biblical Study, Philadelphia, Westminster, ISBN 0-664-25724-0.

- Birch, Bruce C., Walter Brueggemann, Terence E. Fretheim, and David L. Petersen (1999). A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament, ISBN 0-687-01348-8.

- Coggins, R. J., and J. L. Houlden, eds. (1990). Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation. London: SCM Press; Philadelphia: Trinity Press International. ISBN 0-334-00294-X.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-073817-0.

- Fuller, Reginald H. (1965). The Foundations of New Testament Christology. Scribners. ISBN 0-684-15532-X.

- Goldingay, John (1990). Approaches to Old Testament Interpretation. Rev. ed. Downers Grove, IL, InterVarsity, ISBN 1-894667-18-2.

- Hayes, John H., and Carl R. Holladay (1987). Biblical Exegesis: A Beginner's Handbook, Rev. ed. Atlanta, GA, John Knox, ISBN 0-8042-0031-9.

- Knight, Douglas A., and Gene M. Tucker, eds. (1993). To Each Its Own Meaning: An Introduction to Biblical Criticisms and Their Applications, Louisville, KY, Westminster/John Knox, ISBN 0-664-25784-4.

- Morgan, Robert, and John Barton (1988). Biblical Interpretation, New York, Oxford University, ISBN 0-19-213257-1.

- Soulen, Richard N. (1981). Handbook of Biblical Criticism, 2nd ed. Atlanta, Ga, John Knox, ISBN 0-664-22314-1.

- Stuart, Douglas (1984). Old Testament Exegesis: A Primer for Students and Pastors, 2nd ed., Philadelphia, Westminster, ISBN 0-664-24320-7.

- Shinan, Avigdir, and Yair Zakovitch (2004). That's Not What the Good Book Says, Miskal-Yediot Ahronot Books and Chemed Books, Tel-Aviv

External links

PDF Teaching Bible from the point of view of Biblical criticism.

PDF Teaching Bible from the point of view of Biblical criticism.- A good introduction at Theopedia

- History of Jewish Secular Thought, Chapter 4: Bible, from Oberlin College Jewish studies program.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.