Ayman al-Zawahiri

| Ayman al-Zawahiri | |

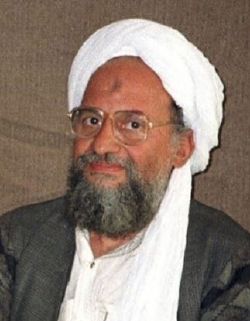

al-Zawahri in 2001 | |

2nd General Emir of Al-Qaeda

| |

| In office June 16, 2011[1] – July 31, 2022 | |

| Preceded by | Osama bin Laden |

|---|---|

Deputy Emir of Al-Qaeda

| |

| In office 1988 – 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Nasir al-Wuhayshi |

Emir of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad

| |

| In office 1991 – 1998 | |

| Preceded by | Muhammad abd-al-Salam Faraj |

| Succeeded by | Position disestablished (merged with Al-Qaeda) |

| Born | June 19 1951 Giza, Kingdom of Egypt |

| Died | July 31 2022 (aged 71) Kabul, Afghanistan |

| Spouse | Azza Ahmed (m. 1978; died 2001) Umaima Hassan |

| Children | 7 |

| Alma mater | Cairo University |

| Occupation | Surgeon |

Ayman Mohammed Rabie al-Zawahiri[2][3] (June 19, 1951 – July 31, 2022) was an Egyptian-born terrorist and physician who served as the second emir of al-Qaeda from June 16, 2011, until his death.

Al-Zawahiri was a surgeon by profession, who graduated from Cairo University with a degree in medicine and a master's degree in surgery. He became a leading figure in the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, an Egyptian Islamist organization, and eventually attained the rank of emir. He was imprisoned from 1981 to 1984 for his role in the assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. His actions against the Egyptian government, including his planning of the 1995 attack on the Egyptian Embassy in Pakistan, resulted in him receiving a death sentence in absentia during the 1999 "Returnees from Albania" trial.

| Ayman al-Zawahiri | |

|---|---|

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1980–2022 |

| Rank | General Emir of Al-Qaeda |

| Battles/wars |

|

A close associate of al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, al-Zawahiri held significant sway over the group's operations. Al-Zawahiri was wanted by the United States and the United Nations, respectively, for his role in the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania and in the 2002 Bali bombings. He merged the Egyptian Islamic Jihad with al-Qaeda in 2001 and formally became bin Laden's deputy in 2004. He succeeded bin Laden as al-Qaeda's leader after bin Laden's death in 2011. In May 2011, the U.S. announced a $25 million bounty for information leading to his capture.

On July 31, 2022, al-Zawahiri was killed in a U.S. drone strike in Afghanistan.

Personal life

Early life

Ayman al-Zawahiri was born June 19, 1951, in Giza,[7][8] in the then Kingdom of Egypt, to Mohammed Rabie al-Zawahiri and Umayma Azzam.[9]

The New York Times in 2001 described al-Zawahiri as coming from "a prosperous and prestigious family that gives him a pedigree grounded firmly in both religion and politics."[10] Al-Zawahiri's parents both came from prosperous families. Al-Zawahiri's father, Mohammed Rabie al-Zawahiri, came from a large family of doctors and scholars from Kafr Ash Sheikh Dhawahri, Sharqia, in which one of his grandfathers was Sheikh Muhammad al-Ahmadi al-Zawahiri (1887–1944), the 34th Grand Imam of al-Azhar.[11] Mohammed Rabie became a surgeon and a professor of pharmacy[12] at Cairo University. Ayman Al-Zawahiri's mother, Umayma Azzam, came from a wealthy, politically active clan, the daughter of Abdel-Wahhab Azzam, a literary scholar who served as the president of Cairo University, the founder and inaugural rector of the King Saud University (the first university in Saudi Arabia) as well as ambassador to Pakistan. His brother was Azzam Pasha, the founding secretary-general of the Arab League (1945–1952).[13] From his maternal side yet another relative was Salem Azzam, an Islamist intellectual and activist, for a time secretary-general of the Islamic Council of Europe based in London.[14] The wealthy and prestigious family is also linked to the Red Sea Harbi tribe in Zawahir, a small town in Saudi Arabia, located in the Badr.[15] He also has a maternal link to the house of Saud: Muna, the daughter of Azzam Pasha (his maternal great-uncle), is married to Mohammed bin Faisal Al Saud, the son of the late king Faisal.[16]

Ayman Al-Zawahiri said that he has a deep affection for his mother. Her brother, Mahfouz Azzam, became a role model for him as a teenager.[17] He has a younger brother, Muhammad al-Zawahiri, and a twin sister, Heba Mohamed al-Zawahiri.[18] Al-Zawahiri's sister, Heba Mohamed al-Zawahiri, became a professor of medical oncology at the National Cancer Institute, Cairo University. She described her brother as "silent and shy."[19] Muhammad was sentenced on charges of undergoing military training in Albania in 1998.[20] He was arrested in the UAE in 1999, and sentenced to death in 1999 after being extradited to Egypt.[18][21] He was held in Tora Prison in Cairo as a political detainee. Security officials said he was the head of the Special Action Committee of Islamic Jihad, which organized terrorist operations. After the Egyptian popular uprising in the spring of 2011, he was released from prison on March 17, 2011 by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the interim government of Egypt. His lawyer said he had been held to extract information about his brother, Ayman al-Zawahiri.[22] On March 20, 2011, he was re-arrested.[23] On August 17, 2013, Egyptian authorities arrested Muhammad al-Zawahiri at his home in Giza.[24] He was acquitted in 2017.[25]

Youth

Ayman al-Zawahiri was reportedly a studious youth. He excelled in school, loved poetry, and "hated violent sports," which he thought were "inhumane." Al-Zawahiri studied medicine at Cairo University and graduated in 1974 with gayyid giddan, roughly on par with a grade of "B" in the American grading system. Following that, he served three years as a surgeon in the Egyptian Army after which he established a clinic near his parents in Maadi.[26] In 1978, he also earned a master's degree in surgery.[27] He spoke Arabic, English,[28] and French.[29]

Al-Zawahiri participated in youth activism as a student. He became both quite pious and political, under the influence of his uncle Mahfouz Azzam, and lecturer Mostafa Kamel Wasfi.[30] Sayyid Qutb preached that to restore Islam and free Muslims, a vanguard of true Muslims modeling itself after the original Companions of the Prophet had to be developed.[31] Ayman al-Zawahiri was influenced by Qutb's Manichaean views on Islamic theology and Islamic history.[32]

Underground cell

By the age of 15, al-Zawahiri had formed an underground cell with the goal to overthrow the government and establish an Islamist state. The following year the Egyptian government executed Sayyid Qutb for conspiracy. Following the execution, al-Zawahiri, along with four other secondary school students, helped form an "underground cell devoted to overthrowing the government and establishing an Islamist state." It was at this early age that al-Zawahiri developed a mission in life, "to put Qutb's vision into action."[33] His cell eventually merged with others to form al-Jihad or Egyptian Islamic Jihad.[34]

Marriages and children

Ayman al-Zawahiri was married at least four times. His wives include Azza Ahmed Nowari and Umaima Hassan.

In 1978, al-Zawahiri married his first wife, Azza Ahmed Nowari, a student at Cairo University who was studying philosophy. Their wedding, which was held at the Continental Hotel in Opera Square,[30] was very conservative, with separate areas for both men and women, and no music, photographs, or gaiety in general.[35] Many years later, when the United States attacked Afghanistan in October 2001 following the September 11 attacks, Azza apparently had no idea that al-Zawahiri had supposedly been a jihadi emir (commander) for the last decade.[36]

Al-Zawahiri and his wife, Azza, had four daughters, Fatima (born 1981), Umayma (born 1983), Nabila (born 1986), and Khadiga (born 1987), and a son, Mohammed (also born in 1987; the twin brother of Khadiga), who was a "delicate, well-mannered boy" and "the pet of his older sisters." He was subject to teasing and bullying in a traditionally all-male environment, who preferred to "stay at home and help his mother."[37] In 1997, ten years after the birth of Mohammed, Azza gave birth to their fifth daughter, Aisha, who had Down syndrome. In February 2004, Abu Zubaydah was waterboarded and subsequently stated that Abu Turab Al-Urduni had married one of al-Zawahiri's daughters.[38]

Ayman al-Zawahiri's first wife Azza and two of their six children, Mohammad and Aisha, were killed in an airstrike on Afghanistan by US forces in late December 2001, following the September 11 attacks on the U.S.[39][40] After an American aerial bombardment of a Taliban-controlled building at Gardez, Azza was pinned under the debris of a guesthouse roof. Concerned for her modesty, she "refused to be excavated" because "men would see her face" and she died from her injuries the following day. Her son, Mohammad, was also killed during the raid. Her four-year-old daughter with Down syndrome, Aisha, had not been hurt by the bombing, but died from exposure in the cold night while Afghan rescuers tried to save Azza.[41]

In the first half of 2005, one of Al-Zawahiri's three surviving wives gave birth to a daughter, named Nawwar.[42]

Medical career

Ayman al-Zawahiri worked as a surgeon. In 1985, al-Zawahiri went to Saudi Arabia on Hajj and stayed to practice medicine in Jeddah for a year.[43] As a reportedly qualified surgeon, when his organization merged with bin Laden's al-Qaeda, he became bin Laden's personal advisor and physician. He had first met bin Laden in Jeddah in 1986.[44] According to other sources, they met the first time in 1986 at a hospital in Peshawar, Pakistan.[45]

In 1981, Ayman al-Zawahiri traveled to Peshawar, where he worked in a Red Crescent hospital treating wounded refugees. There, he became friends with Ahmed Khadr, and the two shared a number of conversations about the need for Islamic government and the needs of the Afghan people.[46]

In 1993, al-Zawahiri traveled to the United States, where he addressed several mosques in California under his Abdul Mu'iz pseudonym, relying on his credentials from the Kuwaiti Red Crescent to raise money for Afghan children who had been injured by Soviet land mines—he raised only $2000.[47]

Militant activity

Assassination plots

Egypt

In 1981, Al-Zawahiri was one of hundreds arrested following the assassination of President Anwar Sadat.[48] The initial plan was derailed when, in February 1981, authorities were alerted to Al-Jihad's plan by the arrest of an operative carrying crucial information. President Sadat ordered the roundup of more than 1,500 people, including many Al-Jihad members, but missed a cell in the military led by Lieutenant Khalid Islambouli, who succeeded in assassinating Sadat during a military parade that October.[49] His lawyer, Montasser el-Zayat, said that al-Zawahiri was tortured in prison.[50]

In his book, Al-Zawahiri as I Knew Him, Al-Zayat maintains that following his arrest in connection with the murder of Sadat in 1981 Al-Zawahiri revealed under torture the hiding place of Essam al-Qamari, a key member of the Maadi cell of al-Jihad. It led to Al-Qamari's "arrest and eventual execution."[51] He was released from prison in 1984.

In 1993, al-Zawahiri's and Egyptian Islamic Jihad's (EIJ) connection with Iran may have led to a suicide bombing in an attempt on the life of Egyptian Interior Minister Hasan al-Alfi, the man heading the effort to quash the campaign of Islamist killings in Egypt. It failed, as did an attempt to assassinate Egyptian prime minister Atef Sidqi three months later. The bombing of Sidqi's car injured 21 Egyptians and killed a schoolgirl, Shayma Abdel-Halim. It followed two years of killings by another Islamist group, al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, that had killed over 200 people. Her funeral became a public spectacle, with her coffin carried through the streets of Cairo and crowds shouting, "Terrorism is the enemy of God!"[52] The police arrested 280 more of al-Jihad's members and executed six.[53]

For their leading role in anti-Egyptian Government attacks in the 1990s, al-Zawahiri and his brother Muhammad al-Zawahiri were sentenced to death in the 1999 Egyptian case of the Returnees from Albania.[18][21]

Pakistan

The 1995 attack on the Egyptian embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan, was carried out by the Egyptian Islamic Jihad under al-Zawahiri's leadership, but Bin Laden had disapproved of the operation. The bombing alienated Pakistan, which was "the best route into Afghanistan."[54]

In July 2007, Al-Zawahiri supplied direction for the Lal Masjid siege, codename Operation Silence. This was the first confirmed time that Al-Zawahiri was taking militant steps against the Pakistani Government and guiding Islamic militants against the State of Pakistan. The Pakistan Army troops and Special Service Group taking control of the Lal Masjid ("Red Mosque") in Islamabad found letters from al-Zawahiri directing Islamic militants Abdul Rashid Ghazi and Abdul Aziz Ghazi, who ran the mosque and adjacent madrasah. This conflict resulted in 100 deaths.[55]

On December 27, 2007, al-Zawahiri was also implicated in the assassination of former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.[56]

Sudan

In 1994, the sons of Ahmad Salama Mabruk and Mohammed Sharaf were executed under al-Zawahiri's leadership for betraying Egyptian Islamic Jihad; the militants were ordered to leave the Sudan.[57][58]

United States

In 1998, Ayman al-Zawahiri was listed as under indictment[59] in the United States for his role in the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings: a series of attacks on August 7, 1998, in which hundreds of people were killed in simultaneous truck bomb explosions at the United States embassies in the major East African cities of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Nairobi, Kenya.[60]

In 2000, the USS Cole bombing encouraged several members to depart. Mohammed Atef escaped to Kandahar, al-Zawahiri to Kabul, and Bin Laden also fled to Kabul, later joining Atef when he realized no American reprisal attacks were forthcoming.[61]

On October 10, 2001, al-Zawahiri appeared on the initial list of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation's top 22 Most Wanted Terrorists, which was released to the public by U.S. President George W. Bush. In early November 2001, the Taliban government announced they were bestowing official Afghan citizenship on him, as well as Bin Laden, Mohammed Atef, Saif al-Adl, and Shaykh Asim Abdulrahman.[62]

Organizations

Egyptian Islamic Jihad

Al-Zawahiri began reconstituting the Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) along with other exiled militants.

In Peshwar, al-Zawahiri was thought to have become radicalized by other Al-Jihad members, abandoning his old strategy of a swift coup d'état to change society from above, and embracing the idea of takfir.[63] In 1991, EIJ broke with al-Zumur, and al-Zawahiri grabbed "the reins of power" to become EIJ leader.

Ayman al-Zawahiri was previously the second and last "emir" of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, having succeeded Abbud al-Zumar in the role when Egyptian authorities sentenced al-Zumar to life imprisonment. Ayman al-Zawahiri eventually became one of Egyptian Islamic Jihad's leading organizers and recruiters. Al-Zawahiri's hope was to recruit military officers and accumulate weapons, waiting for the right moment to launch "a complete overthrow of the existing order."[64] Chief strategist of Al-Jihad was Aboud al-Zumar, a colonel in the military intelligence whose plan was to kill the main leaders of the country, capture the headquarters of the army and State Security, the telephone exchange building, and of course the radio and television building. From there news of the Islamic revolution would then be broadcast, unleashing – he expected – "a popular uprising against secular authority all over the country."[65]

Maktab al-Khadamat

In Peshawar, he made contact with Osama bin Laden, who was running a base for mujahideen called Maktab al-Khadamat (MAK), founded by the Palestinian Sheikh Abdullah Yusuf Azzam. The radical position of al-Zawahiri and the other militants of Al-Jihad put them at odds with Sheikh Azzam, with whom they competed for bin Laden's financial resources.[66] Al-Zawahiri carried two false passports, a Swiss one in the name of Amin Uthman and a Dutch one in the name of Mohmud Hifnawi.

British journalist Jason Burke wrote: "Al-Zawahiri ran his own operation during the Afghan war, bringing in and training volunteers from the Middle East. Some of the $500 million the CIA poured into Afghanistan reached his group."[67]

Former FBI agent Ali Soufan mentioned in his book The Black Banners that Ayman al-Zawahiri is suspected of ordering Azzam's assassination in 1989.[68]

Al-Qaeda

According to reports by a former al-Qaeda member, al-Zawahiri worked in the al-Qaeda organization since its inception and was a senior member of the group's shura council. He was often described as a "lieutenant" to Osama bin Laden, though bin Laden's chosen biographer has referred to him as the "real brains" of al-Qaeda.[70]

On February 23, 1998, al-Zawahiri issued a joint fatwa with Osama bin Laden under the title "World Islamic Front Against Jews and Crusaders." It was Al-Zawahiri, not bin Laden, who was thought to have been the actual author of the fatwa.[71]

Bin Laden and al-Zawahiri organized an al-Qaeda congress on June 24, 1998. A week prior to the beginning of the conference, a group of well-armed assistants to al-Zawahiri had left by jeeps in the direction of Herat. Following the instructions of their patron, in the town of Koh-i-Doshakh, they met three unknown "Slavic-looking men" who had arrived from Russia via Iran. After their arrival in Kandahar, they split up. One of the Russians was directly escorted to al-Zawahiri, who did not participate in the conference. Western military intelligence succeeded in acquiring photographs of him, but he disappeared for six years. According to Axis Globe, in 2004, when Qatar and the U.S. investigated Russian embassy officials whom the United Arab Emirates had arrested in connection to the murder of Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev in Qatar, computer software precisely established that a man who had walked to the Russian embassy in Doha was the same one who visited al-Zawahiri prior to the Al-Qaeda conference.[72]

Al-Zawahiri was placed under international sanctions in 1999 by the United Nations' Al-Qaida and Taliban Sanctions Committee as a member of the Salafi-jihadist group al-Qaeda.[73]

In June 2001, al-Zawahiri formally merged the Egyptian Islamic Jihad into al-Qaeda.[74]

In late 2001, a computer was seized that was stolen from an office used by al-Qaeda immediately after the fall of Kabul in November. This computer was mainly used by al-Zawahiri and contained the letter with an interview request for Ahmad Shah Massoud. The journalists who conducted the interview assassinated Massoud on September 9, 2001.[75]

Emergence as al-Qaeda's chief commander

In late 2004 bin Laden named al-Zawahiri officially as his deputy.[76] On April 30, 2009, the U.S. State Department reported that al-Zawahiri had emerged as al-Qaeda's operational and strategic commander,[77] and that Osama bin Laden was now only the ideological figurehead of the organization. After the 2011 death of bin Laden, a senior U.S. intelligence official said intelligence gathered in the raid showed that bin Laden remained deeply involved in planning: "This compound (where bin Laden was killed) in Abbottabad was an active command-and-control center for al-Qaeda's leader. He was active in operational planning and in driving tactical decisions within al-Qaeda."[78]

Following the death of bin Laden, former U.S. Deputy National Security Advisor for Combating Terrorism Juan Zarate said that al-Zawahiri would "clearly assume the mantle of leadership" of al-Qaeda." A senior U.S. administration official said that although al-Zawahiri was likely to be al-Qaeda's next leader, his authority was not "universally accepted" among al-Qaeda's followers, particularly in the Gulf region. Zarate said that al-Zawahiri was more controversial and less charismatic than bin Laden.[79] Rashad Mohammad Ismail (AKA "Abu Al-Fida"), a leading member of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, stated that al-Zawahiri was the best candidate.[80]

Hamid Mir is reported to have said that he believed that Ayman al-Zawahiri was the operational head of al-Qaeda, and that "[h]e is the person who can do the things that happened on September 11."[70] Within days of the attacks, al-Zawahiri's name was put forward as bin Laden's second-in-command, with reports suggesting he represented "a more formidable US foe than bin Laden."[81]

Formal appointment

Al-Zawahiri became the leader of al-Qaeda following the May 2, 2011 killing of Osama bin Laden. His succession to that role was announced on several of their websites on June 16, 2011.[40] On the same day, al-Qaeda renewed its position that Israel was an illegitimate state and that it would not accept any compromise on Palestine.[82]

The delayed announcement led some analysts to speculate that there was quarreling within al-Qaeda: "It doesn't suggest a vast reservoir of accumulated goodwill for him," said one journalist on CNN.[83] Both U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mike Mullen maintain that the delay didn't signal any kind of dispute within al-Qaeda,[84] and Mullen reiterated U.S. death threats toward al-Zawahiri. According to US officials within the Obama administration and Robert Gates, al-Zawahiri would find the leadership difficult as, while intelligent, he lacks combat experience and the charisma of Osama bin Laden.[85]

Activities in Iran

Al-Zawahiri allegedly worked with the Islamic Republic of Iran on behalf of al-Qaeda. Author Lawrence Wright reports that EIJ operative Ali Mohammed "told the FBI that al-Jihad had planned a coup in Egypt in 1990." Al-Zawahiri had studied the 1979 Islamist Islamic Revolution and "sought training from the Iranians" as to how to duplicate their feat against the Egyptian government.

He offered Iran information about an Egyptian government plan to storm several islands in the Persian Gulf that both Iran and the United Arab Emirates lay claim to. According to Mohammed, in return for this information, the Iranian government paid al-Zawahiri $2 million and helped train members of al-Jihad in a coup attempt that never actually took place.[86]

In public, al-Zawahiri harshly denounced the Iranian government. In December 2007, he said, "We discovered Iran collaborating with America in its invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq."[87] In the same video messages, he chides Iran for "repeating the ridiculous joke that says that al-Qaida and the Taliban are agents of America," before playing a video clip in which Ayatollah Rafsanjani says, "In Afghanistan, they were present in Afghanistan, because of Al-Qa'ida; and the Taliban, who created the Taliban? America is the one who created the Taliban, and America's friends in the region are the ones who financed and armed the Taliban."[87]

Al-Zawahiri, a Sunni, criticized Iran's Shiite government for failing to call for jihad against the Americans.

Despite Iran's repetition of the slogan 'Death to America, death to Israel,' we haven't heard even one Fatwa from one Shiite authority, whether in Iran or elsewhere, calling for Jihad against the Americans in Iraq and Afghanistan.[87]

Al-Zawahiri said that "stabbed a knife into the back of the Islamic Nation."[88]

In April 2008, al-Zawahiri blamed Iranian state media and Al-Manar for perpetuating the "lie" that "there are no heroes among the Sunnis who can hurt America as no-one else did in history" in order to discredit the Al Qaeda network.[89] Al-Zawahiri was referring to some 9/11 conspiracy theories that claim that Al Qaeda was not responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

On the seventh anniversary of the attacks of September 11, 2001, al-Zawahiri released a 90-minute tape[90] in which he blasted "the guardian of Muslims in Tehran" for recognizing "the two hireling governments"[91] in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Activities in Russia

At some point in 1994, al-Zawahiri was said to have "become a phantom"[92] but is thought to have traveled widely to "Switzerland and Sarajevo." A fake passport he was using shows that he traveled to Malaysia, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong.[93]

On December 1, 1996, Ahmad Salama Mabruk and Mahmud Hisham al-Hennawi – both carrying false passports – accompanied al-Zawahiri on a trip to Chechnya, where they hoped to re-establish the faltering Jihad. Their leader was traveling under the pseudonym Abdullah Imam Mohammed Amin, and trading on his medical credentials for legitimacy. The group switched vehicles three times, but were arrested within hours of entering Russian territory and spent five months in a Makhachkala prison awaiting trial. The trio pleaded innocent, maintaining their ruse while other al-Jihad members from Bavari-C sent the Russian authorities pleas for leniency for their "merchant" colleagues who had been wrongly arrested. Russian Member of Parliament Nadyr Khachiliev echoed the pleas for their speedy release as al-Jihad members Ibrahim Eidarous and Tharwat Salah Shehata traveled to Dagestan to plead for their release. Shehata received permission to visit the prisoners. He is believed to have smuggled $3000 to them, which was later confiscated, and to have given them a letter which the Russians didn't bother to translate. In April 1997 the trio were sentenced to six months, were subsequently released a month later, and absconded without paying their court-appointed attorney Abulkhalik Abdusalamov his $1,800 legal fee, citing "poverty."[94] Shehata was sent on to Chechnya where he met with Ibn Khattab.[95][96]

There have been doubts as to the true nature of al-Zawahiri's encounter with the Russians in 1996. Jamestown Foundation scholar Evgenii Novikov has argued that it seems unlikely that the Russians would not have been able to determine who he was, given Russia's well-trained Arabists and the suspicious acts of Muslims crossing borders illegally with multiple Arabic false identities and encrypted documents.[97][98] Assassinated former FSB secret service officer Alexander Litvinenko alleged, among other things, that during this time al-Zawahiri was trained by the FSB[99] and that he was not the only link between al-Qaeda and the FSB.[100][101] Former KGB officer, Voice of America commentator and writer Konstantin Preobrazhenskiy supported Litvinenko's claim. He said that Litvinenko "was responsible for securing the secrecy of Al-Zawahiri's arrival in Russia, who was trained by FSB instructors in Dagestan, Northern Caucasus, during 1996–1997."[102]

Activities in Egypt

Al-Zawahiri was convicted of dealing in weapons and received a three-year sentence, which he completed in 1984, shortly after his conviction.[103]

Al-Zawahiri learned of a "Nonviolence Initiative" organized in Egypt to end the terror campaign that had killed hundreds and resulting government crackdown that had imprisoned thousands. Al-Zawahiri angrily opposed this "surrender" in letters to the London newspaper Al-Sharq al-Awsat.[104] Together with members of al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, he helped organize a massive attack on tourists at the Temple of Hatshepsut to sabotage the initiative by provoking the government into repression.[105]

The attack by six men dressed in police uniforms succeeded in machine-gunning and hacking to death 58 foreign tourists and four Egyptians, including "a five-year-old British child and four Japanese couples on their honeymoons," devastating the Egyptian tourist industry for a number of years. Nonetheless, the Egyptian reaction was not what al-Zawahiri had hoped for. The attack so stunned and angered Egyptian society that Islamists denied responsibility. Al-Zawahiri blamed the police for the killing, but also held the tourists responsible for their own deaths for coming to Egypt,

The people of Egypt consider the presence of these foreign tourists to be aggression against Muslims and Egypt... The young men are saying that this is our country and not a place for frolicking and enjoyment, especially for you.[106]

Al-Zawahiri was sentenced to death in absentia in 1999 by an Egyptian military tribunal.[107]

Activities and whereabouts after the September 11 attacks

In December 2001, al-Zawahiri published a book entitled Fursan Taht Rayat al Nabi[108] (Knights Under the Prophet's Banner) which outlined ideologies of al-Qaeda.[109] English translations of this book were published; excerpts are available online.[110]

...It seeks revenge against the gang-leaders of global unbelief, the United States, Russia, and Israel. It demands the blood price for the martyrs, the mothers' grief, the deprived orphans, the suffering prisoners, and the torments of those who are tortured everywhere in the Islamic lands―from Turkistan in the east to Andalusia.[114]

Following the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, al-Zawahiri's whereabouts were unknown, but he was generally thought to be in tribal Pakistan. Although he released videos of himself frequently, al-Zawahiri did not appear alongside bin Laden in any of them after 2003. In 2003, it was rumored that he was under arrest in Iran, although this was later discovered to be false.[118]

Attempts on al-Zawahiri's life

On January 13, 2006, the Central Intelligence Agency, aided by Pakistan's ISI, launched an airstrike on Damadola, a Pakistani village near the Afghan border where they believed al-Zawahiri was located. The airstrike was supposed to kill al-Zawahiri. It was widely reported in international news over the following days. Many victims of the airstrike were buried unidentified. Anonymous U.S. government officials claimed that some terrorists were killed and the Bajaur tribal area government confirmed that at least four terrorists were among the dead.[119] Anti-American protests broke out around the country and the Pakistani government condemned the U.S. attack and the loss of innocent life.[120]

On August 1, 2008, CBS News reported that it had obtained a copy of an intercepted letter dated July 29, 2008, from unnamed sources in Pakistan, which urgently requested a doctor to treat al-Zawahiri. The letter indicated that al-Zawahiri was critically injured in a US missile strike at Azam Warsak village in South Waziristan on July 28 that also reportedly killed al Qaeda explosives expert Abu Khabab al-Masri. Taliban Mehsud spokesman Maulvi Umar told the Associated Press on August 2, 2008, that the report of al-Zawahiri's injury was false.[121]

In early September 2008, Pakistan Army claimed that they "almost" captured al-Zawahiri after getting information that he and his wife were in the Mohmand Agency, in northwest Pakistan. After raiding the area, officials didn't find him.[122]

Later activities

In two videos posted on Jihadist websites in 2012, al-Zawahiri called on Muslims to "capture" foreign citizens to leverage the release of Omar Abdel-Rahman, mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.[123] In the videos, al-Zawahiri cited to the successful kidnapping of Jewish American Warren Weinstein in 2011 as precedent for further kidnappings. Al-Zawahiri also called for the institution of Sharia law in Egypt and questioned the views of then-President of Egypt Mohamed Morsi.

In September 2015, al-Zawahiri urged Islamic State (ISIL) to stop fighting al-Nusra Front, the official al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria,[124] and to unite with all other jihadists against the supposed alliance between America, Russia, Europe, Shiites and Iran, and Bashar al-Assad's Alawite regime.[125][126]

Ayman al-Zawahiri released a statement supporting jihad in Xinjiang against Chinese, jihad in the Caucasus against the Russians and naming Somalia, Yemen, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan as battlegrounds.[127] al-Zawahiri endorsed "jihad to liberate every span of land of the Muslims that has been usurped and violated, from Kashgar to Andalusia, and from the Caucasus to Somalia and Central Africa".[128] Muslim Uyghurs inhabit the city of Kashgar. In another statement he said, "My mujahideen brothers in all places and of all groups ... we face aggression from America, Europe, and Russia ... so it's up to us to stand together as one from East Turkestan to Morocco".[129][130] In 2015, the Turkistan Islamic Party (East Turkistan Islamic Movement) released an image showing Al Qaeda leaders Ayman al-Zawahiri and Osama Bin Laden meeting with Hasan Mahsum.

The Uyghurs' East Turkestan independence movement was endorsed in the serial "Islamic Spring"'s 9th release by Al-Zawahiri. Al-Zawahiri confirmed that the Afghanistan war after 9/11 included the participation of Uyghurs and that the jihadists like Zarwaqi, Bin Ladin and the Uyghur Hasan Mahsum were provided with refuge together in Afghanistan under Taliban rule.[131] Uyghur fighters were praised by al-Zawahiri, before a Turkistan Islamic Party performed a Bishkek bombing on August 30.[132] Uighur jihadists were hailed by Ayman al-Zawahiri.[133]

Death

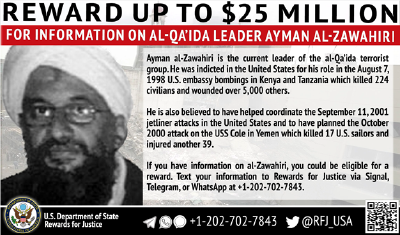

The Rewards for Justice Program of the U.S. Department of State offered a reward of up to US$25 million for information about al-Zawahiri's location.[134]

Al-Zawahiri was killed on July 31, 2022, shortly after 6:00 AM local time in an early-morning drone strike conducted by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in the upscale Sherpur neighborhood of Kabul, reportedly in a house owned by a top aide to Sirajuddin Haqqani, a senior official in the Taliban government.[135]

He had been rumoured to be in Pakistan's tribal area or inside Afghanistan. His death is considered to be the biggest hit to the terrorist group since Osama Bin Laden was killed in 2011.[136] Others described his death as "anticlimactic to Al Qaeda's demise," stating "[h]is moves as leader of the shrinking group were watched more by analysts than by jihadists" at the time of his death.[137]

In a statement to reporters, a senior administration official said "over the weekend, the United States conducted a counterterrorism operation against a significant Al Qaeda target in Afghanistan. The operation was successful and there were no civilian casualties."[135] The United St ates Department of Defense denied responsibility for the strike, while the United States Central Command declined to comment. On the evening of August 1, delayed by two days to allow time for proper verification of the operation's success, President Joe Biden announced at the White House that the U.S. Intelligence Community had located al-Zawahiri as he moved into downtown Kabul in early 2022 and had authorized the operation a week prior. Biden also stated that the operation incurred no civilian casualties nor had it harmed any members of al-Zawahiri's family.[138]

According to U.S. government sources, Al-Zawahiri was killed by Hellfire missiles fired from a drone.Press sources have speculated that the missiles may have been R9X Hellfire missiles, which are designed to kill with blades instead of explosion to avoid unintended casualties.[139][140]

Notes

- ↑ "Al-Qaeda's remaining leaders," BBC, June 16, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Arabic: أيمن محمد ربيع الظواهري

- ↑ Al-Zawahiri is also sometimes transliterated al-Dhawahiri to reflect normative classical Arabic pronunciation beginning with /ðˤ/.. The Egyptian Arabic pronunciation is ˈʔæjmæn mæˈħæmmæd ɾɑˈbiːʕ ez.zˤɑˈwɑhɾi; approximately: Ayman Mahammad Rabi Ezzawahri.

- ↑ "Ayman al-Zawahiri – from medical doctor to al Qaeda chief," DW, August 1, 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ↑ Winfried F. Schmitz, Solutions Looking Beyond Evil (Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, 2016, ISBN 978-1524540395

- ↑ "Ayman al Zawahiri," Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Ayman al-Zawahiri – Rewards For Justice," Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Amends One Entry on Its Sanctions List," United Nations, May 22, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Bruce O. Riedel, The search for al Qaeda : its leadership, ideology, and future (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0815704522), 16.

- ↑ Douglas Jehl, "A Nation Challenged: Heir Apparent; Egyptian Seen As Top Aide And Successor To bin Laden," The New York Times, September 24, 2001. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Youssef H. Aboul-Enein, "Ayman Al-Zawahiri: The Ideologue of Modern Islamic Militancy," Air University – Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama March 2004, 1. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Ayman al-Zawahiri Fast Facts," CNN', August 4, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Olivier Roy and Antoine Sfeir, eds., The Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0231131308), 419.

- ↑ Lorenzo Vidino, The New Muslim Brotherhood in the West (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0231151269), 234.

- ↑ David Boukay, From Muhammad to Bin Laden: Religious and Ideological Sources of the Homicide Bombers Phenomenon (London, UK: Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-0765803900), 1.

- ↑ "Family Tree of Muhammad bin Faysal bin Abd al-Aziz Al Saud," Datarabia. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Lawrence Wright, The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 (New York, NY: Alfred Knopf, 2006, ISBN 037541486X), Chapter 2.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Black Hole: The Fate of Islamists Rendered to Egypt: VI. Muhammad al-Zawahiri and Hussain al-Zawahiri," Human Rights Watch. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Francesco Battistini, "La sorella del nuovo Osama: Mio fratello Al Zawahiri, così timido e silenzioso," Corriere della Sera, June 12, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Egyptian court acquits Mohammed Zawahiri and brother of Sadat's assassin," Alarabiya News, March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Muhammad al-Zawahiri," Counter Extremism Project. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Liam Stack, Egypt Releases Brother of Al Qaeda's No. 2," The New York Times, March 17, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Sherif Tarek, "Brother of Al-Qaeda's Zawahri re-arrested," Ahram Online, March 20, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Egypt arrests brother of Qaeda chief for 'backing Morsi'," Middle East Online, August 17, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Final court verdict acquits Mohamed Al-Zawahiri of terrorist charges," Daily News Egypt, August 1, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 42.

- ↑ Peter L. Bergen, The Osama bin Laden I Know: An Oral History of al Qaeda's Leader (New York, NY: Free Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0743278911), 66.

- ↑ Isambard Wilkinson, "Al-Qa'eda chief Ayman Zawahiri attacks Pakistan's Pervez Musharraf in video," The Daily Telegraph, London, UK, August 11, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Meet Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Al Qaeda chief who owes allegiance to Taliban supreme leader Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada," Firstpost, August 17, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Monstasser el-Zayyat, The Road to Al-Qaeda: The Story of Bin Laden's Right Hand Man tr. Ahmed Fakry, (London, UK: Pluto Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0745321752).

- ↑ Sayed Qutb, Milestones, (Islamic Book Service, 2006, ISBN 978-8172312442), 17–18.

- ↑ Quintan Wiktorowicz, "A Genealogy of Radical Islam," Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 28(2), August 20, 2006, 75–97. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 37.

- ↑ Wright, 42.

- ↑ Wright, 43–44.

- ↑ Wright, 370.

- ↑ Wright, 254–5.

- ↑ Intelligence report, interrogation of Abu Zubaydah, February 18, 2004.

- ↑ "For al-Zawahiri, anti-U.S. fight is personal," CBS News, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Saad Abedine, "Jihadist websites: Ayman al-Zawahiri appointed al Qaeda's new leader," Cable News Network, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 371.

- ↑ Bergen, 367.

- ↑ Wright, 60.

- ↑ Stephen E. Atkins, The 9/11 Encyclopedia 2nd. ed., (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, LLC., 2011, ISBN 978-1598849219), 456.

- ↑ Peter Bergen, "Opinion: Charisma-free al-Zawahiri was running al-Qaeda into the ground," CNN, August 2, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ John Pike, "Ayman al-Zawahiri," Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 179.

- ↑ "Mohamed al-Zawahiri denies being arrested in Syria," Egypt Independent, May 1, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 50.

- ↑ Owen Bowcott, "Torture trail to September 11: A two-part investigation into state brutality opens with a look at how the violent interrogation of Islamist extremists hardened their views, helped to create al-Qaida and now, more than ever, is fueling fundamentalist hatred," The Guardian, January 24, 2003. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Nimrod Raphaeli, "Ayman Muhammad Rabi' Al-Zawahiri: The Making of an Arch Terrorist," Terrorism and Political Violence 14(4), Winter 2002, 1–22.

- ↑ Wright, 186.

- ↑ "Egyptian Islamic," Middle-East-Encyclopedia, www.mideastweb.org. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 217.

- ↑ Dean Nelson, "Bin Laden’s deputy behind the Red Mosque bloodbath," The Sunday Times, July 15, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Pakistan: Al-Qaeda claims Bhutto's death," Adnkronos Security, December 27, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Mohammed al-Shafey and, "Al-Qaeda's secret Emails: Part Four," Asharq Alawsat, June 19, 2005. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0812238082), 45.

- ↑ "Copy of indictment: USA v. Usama bin Laden et al.," Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Monterey Institute of International Studies. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Ayman al-Zawahiri," FBI Most Wanted Terrorists. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ "National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States," 9/11 Commission, July 22, 2004, 191. Retrieved on September 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Taliban grants Osama citizenship,", The Hindu, November 10, 2001. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 124–125.

- ↑ Wright, 49.

- ↑ Wright, 49.

- ↑ Wright, 103.

- ↑ "Frankenstein the CIA created," The Guardian, January 17, 1999. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Ali H Soufan and Daniel Freedman, The Black Banners: 9/11 and the War against al-Qaeda (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2011, ISBN 978-0393079425), 11, 135.

- ↑ "Egypt – Al Qaeda Chief Urges Westerner Kidnappings," VINnews, April 27, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Scott Baldauf, "The 'cave man' and Al Qaeda," The Christian Science Monitor, October 31, 2001. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 259.

- ↑ Michel Elbaz, "Russian Secret Services' Links With Al-Qaeda," Axis Globe, July 18, 2005. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ "UN list of affiliates of al-Qaeda and the Taliban," July 28, 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Peter L. Bergen, The Rise and Fall of Osama bin Laden (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2021, ISBN 978-1982170523), 142.

- ↑ Steve Coll, Ghost Wars. The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0143034667), 574-576.

- ↑ Nelly Lahoud, The Bin Laden Papers. How the Abbottabad Raid Revealed the Truth about al-Qaeda, Its Leader and His Family (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022, ISBN 978-0300260632), 80–81.

- ↑ "Al Qaeda No. 2 Ayman al-Zawahiri calls the shots, says State Department," New York Daily News May 4, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Charles Hoskinson, "Osama Bin Laden was still in control, U.S. says," Politico, May 7, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Spencer Ackerman, "U.S. Forces Kill Osama bin Laden," Wired News, May 1, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Moneer Al-Omari, "AQAP responds to death of bin Laden," Yemen Times, May 5, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Egyptian surgeon named as Bin Laden's 'heir'," Independent Online, September 24, 2001. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Al-Qaeda: No compromise on Palestine," Associated Press, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Moni Basu, "Analysis: Al-Zawahiri takes al Qaeda's helm when influence is waning," |CNN, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Robert Burns, "Gates: Al-Zawahri is no bin Laden," USA Today, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "US vows to 'capture and kill' Ayman al-Zawahiri," BBC, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 174.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 "Ayman al Zawahiri: Review of Events: As Sahab's Fourth Interview with Zawahiri," www.LauraMansfield.com, December 16, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Al-Zawahiri in Two Recent Messages: 'Iran Stabbed a Knife into the Back of the Islamic Nation;' Urges Hamas to Declare Commitment to Restoring the Caliphate," MEMRI, December 17, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Al-Qaeda accuses Iran of 9/11 lie," BBC, April 22, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Al-Qaida tape blasts Iran for working with U.S.," NBC News, September 8, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Al-Qaida blasts Iran for working with US in tape," International Herald Tribune, March 29, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 250.

- ↑ Wright, 279.

- ↑ Andrew Higgins and Alan Cullison, "Saga of Dr. Zawahri Sheds Light On the Roots of al Qaeda Terror," The Wall Street Journal, July 2, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 250.

- ↑ Khalil Gebara, "The End of Egyptian Islamic Jihad?" The Jamestown Foundation 3(3), February 10, 2005. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Evgenii Novikov, "A Russian agent at the right hand of bin Laden?" The Jamestown Foundation 2(1), January 15, 2004. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ John Schindler, "Exploring Al Qaeda's Murky Connection To Russian Intelligence,"] Business Insider, June 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Obituary: Alexander Litvinenko," BBC News, November 24, 2006. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Sean Osborne, "Ayman al-Zawahiri: Echoes of Alexander Litvinenko," Northeast Intelligence Network, May 6, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Pavel Stroilov, "Moscow's jihadi," The Spectator, June 25, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Konstantin Preobrazhensky, "Russia and Islam are not Separate: Why Russia backs Al-Qaeda," The Centre for Counterintelligence and Security Studies, December 19, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Wright, 57–8.

- ↑ Wright, 255–6.

- ↑ Wright, 256–7.

- ↑ Wright, 257–8.

- ↑ "Profile: Ayman Al-Zawahiri," Al Jazeera, January 6, 2006. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Dr. John Calvert, Islamism: A Documentary and Reference Guide (Boston, MA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, ISBN 978-0313338564), 230.

- ↑ Youssef H. Aboul-Enein, "Ayman Al-Zawahiri's Knights under the Prophet's Banner: the al-Qaeda Manifesto," Military Review, January–February 2005. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Al-Sharq Al-Awsat Publishes Extracts from Al-Jihad Leader Al-Zawahiri's New Book," February 12, 2001. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ David Aaron, In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2008, ISBN 978-0833044020), 187.

- ↑ Laura Mansfield, His Own Words: A Translation and Analysis of the Writings of Dr. Ayman Al Zawahiri (Lulu.com, 2006, ISBN 978-1847288806), 110.

- ↑ Barry Rubin, Islamic Fundamentalism in Egyptian Politics, 2nd Revised Edition, (London, UK and New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, ISBN 978-1349731305), 178.

- ↑ Gilles Kepel, The War for Muslim Minds: Islam and the West (Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0674015753), 95.

- ↑ Barry Rubin and Judith Colp Rubin, Anti-American Terrorism and the Middle East: A Documentary Reader (Oxford, UK and New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0195176599), 49.

- ↑ Alex Strick van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn, An Enemy We Created: The Myth of the Taliban-Al Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan (Oxford, UK and New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0199927319), 63.

- ↑ Faisal Devji, Landscapes of the Jihad: Militancy, Morality, Modernity (Ithica, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0801444371), 64.

- ↑ , "Iran holding Zawahiri, Abu Ghaith; al-Arabiya TV," Agence France-Presse|AFP, June 28, 2003. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Pakistan: At least 4 terrorists killed in U.S. strike – USA Today," USA Today, January 17, 2006. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Pakistan rally against US strike," BBC News, January 15, 2006. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Missile Strike On Al-Zawahri Disputed," Washington Times, August 3, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "No evidence of al Qaeda No. 2's illness or death, U.S. says," CNN, August 1, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Chelsea J. Carter, "Al Qaeda leader calls for kidnapping of Westerners," CNN, October 28, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Gareth Porter, "Gulf allies and 'Army of Conquest," Al-Ahram Weekly, May 28, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Thomas Joscelyn, "Al Qaeda chief calls for jihadist unity to 'liberate Jerusalem'," Long War Journal, November 2, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ Thomas Joscelyn, "Zawahiri calls for jihadist unity, encourages attacks in West," Long War Journal, September 13, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Zawahiri endorses war in Kashmir but says don't hit Hindus in 'Muslim lands'," The Indian Express, September 17, 2013, Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, "Ayman al-Zawahiri's Pledge of Allegiance to New Taliban Leader Mullah Muhammad Mansour," Middle East Forum, August 13, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Al-Qaeda urges fight against West and Russia," Al Arabiya, November 2, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Ali Abdelaty and Eric Knecht, "Al Qaeda chief urges militant unity against Russia in Syria ," ed. Alison Williams, Reuters, November 1, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Thomas Joscelyn, "Zawahiri praises Uighur jihadists in ninth episode of 'Islamic Spring' series," Foundation for Defense of Democracies Long War Journal, July 7, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Uran Botobekov, "Al-Qaeda, the Turkestan Islamic Party, and the Bishkek Chinese Embassy Bombing," The Diplomat, September 29, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Chinese security under threat from Islamic Uighur militancy," Associated Press, Beijing, CN, September 10, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Most Wanted Terrorists – Ayman Al-Zawahiri," Federal Bureau of Investigation, US Department of Justice. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 Alexander Ward, Nahal Toosi, and Lara Seligman,"U.S. kills Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahri in drone strike," Politico, August 1, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ "A Kabul Safe House – How CIA Identified, Killed Al Qaeda Chief Zawahiri," NDTV.com, August 2, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Hassan Hassan, "Zawahiri’s Death Is Anticlimactic to Al Qaeda’s Demise," New Lines Magazine, August 2, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Tal Axelrod, "Biden announces killing of al-Qaeda leader in Kabul: 'Justice has been delivered'," ABC News, August 1, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Eleanor Watson, "Al-Zawahiri was on his Kabul balcony. How Hellfire missiles took him out," CBS News, August 2, 2011.

- ↑ Bernd Debusmann Jr. and Chris Partridge, "Ayman al-Zawahiri: How US strike could kill al-Qaeda leader – but not his family," BBC News, August 3, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aaron, David. In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2008. ISBN 978-0833044020

- Abdelaty, Ali, and Eric Knecht. "Al Qaeda chief urges militant unity against Russia in Syria ," ed. Alison Williams, Reuters, November 1, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Abedine, Saad. "Jihadist websites: Ayman al-Zawahiri appointed al Qaeda's new leader," Cable News Network, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- Aboul-Enein, Youssef H. "Ayman Al-Zawahiri: The Ideologue of Modern Islamic Militancy," Air University – Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama March 2004, 1. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Aboul-Enein, Youssef H. "Ayman Al-Zawahiri's Knights under the Prophet's Banner: the al-Qaeda Manifesto," Military Review, January–February 2005. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Ackerman, Spencer. "U.S. Forces Kill Osama bin Laden," Wired News, May 1, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Al-Omari, Moneer. "AQAP responds to death of bin Laden," Yemen Times, May 5, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Al-Tamimi, Aymenn Jawad. "Ayman al-Zawahiri's Pledge of Allegiance to New Taliban Leader Mullah Muhammad Mansour," Middle East Forum, August 13, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Al-Zayyat, Monstasser. The Road to Al-Qaeda: The Story of Bin Laden's Right Hand Man tr. Ahmed Fakry. London, UK: Pluto Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0745321752

- Atkins, Stephen E. The 9/11 Encyclopedia 2nd. ed., Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, LLC., 2011. ISBN 978-1598849219

- Axelrod, Tal. "Biden announces killing of al-Qaeda leader in Kabul: 'Justice has been delivered'," ABC News, August 1, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Baldauf, Scott. "The 'cave man' and Al Qaeda," The Christian Science Monitor, October 31, 2001. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Basu, Moni. "Analysis: Al-Zawahiri takes al Qaeda's helm when influence is waning," CNN, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Battistini, Francesco. "La sorella del nuovo Osama: Mio fratello Al Zawahiri, così timido e silenzioso," Corriere della Sera, June 12, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Bergen, Peter L. The Osama bin Laden I Know: An Oral History of al Qaeda's Leader. New York, NY: Free Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0743278911

- Bergen, Peter L. "Opinion: Charisma-free al-Zawahiri was running al-Qaeda into the ground," CNN, August 2, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Botobekov, Uran. "Al-Qaeda, the Turkestan Islamic Party, and the Bishkek Chinese Embassy Bombing," The Diplomat, September 29, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Boukay, David. From Muhammad to Bin Laden: Religious and Ideological Sources of the Homicide Bombers Phenomenon. London, UK: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0765803900

- Bowcott, Owen. "Torture trail to September 11: A two-part investigation into state brutality opens with a look at how the violent interrogation of Islamist extremists hardened their views, helped to create al-Qaida and now, more than ever, is fueling fundamentalist hatred," The Guardian, January 24, 2003. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Burns, Robert. "Gates: Al-Zawahri is no bin Laden," USA Today, June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Calvert, John. Islamism: A Documentary and Reference Guide. Boston, MA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. ISBN 978-0313338564

- Carter, Chelsea J. "Al Qaeda leader calls for kidnapping of Westerners," CNN, October 28, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Coll, Steve. Ghost Wars. The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0143034667

- Debusmann Jr., Bernd, and Chris Partridge. "Ayman al-Zawahiri: How US strike could kill al-Qaeda leader – but not his family," BBC News, August 3, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Devji, Faisal. Landscapes of the Jihad: Militancy, Morality, Modernity. Ithica, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0801444371

- Elbaz, Michel. "Russian Secret Services' Links With Al-Qaeda," Axis Globe, July 18, 2005. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Gebara, Khalil. "The End of Egyptian Islamic Jihad?" The Jamestown Foundation 3(3), February 10, 2005. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Hassan, Hassan. "Zawahiri’s Death Is Anticlimactic to Al Qaeda’s Demise," New Lines Magazine, August 2, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Higgins, Andrew, and Alan Cullison. "Saga of Dr. Zawahri Sheds Light On the Roots of al Qaeda Terror," The Wall Street Journal, July 2, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Hoskinson, Charles. "Osama Bin Laden was still in control, U.S. says," Politico, May 7, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Jehl, Douglas. "A Nation Challenged: Heir Apparent; Egyptian Seen As Top Aide And Successor To bin Laden," The New York Times, September 24, 2001. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Joscelyn, Thomas. "Zawahiri calls for jihadist unity, encourages attacks in West," Long War Journal, September 13, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Joscelyn, Thomas. "Al Qaeda chief calls for jihadist unity to 'liberate Jerusalem'," Long War Journal, November 2, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Joscelyn, Thomas. "Zawahiri praises Uighur jihadists in ninth episode of 'Islamic Spring' series," Foundation for Defense of Democracies Long War Journal, July 7, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Kepel, Gilles. The War for Muslim Minds: Islam and the West. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0674015753

- Lahoud, Nelly. The Bin Laden Papers. How the Abbottabad Raid Revealed the Truth about al-Qaeda, Its Leader and His Family. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022. ISBN 978-0300260632

- Mansfield, Laura. His Own Words: A Translation and Analysis of the Writings of Dr. Ayman Al Zawahiri. Lulu.com, 2006. ISBN 978-1847288806

- Nelson, Dean. "Bin Laden’s deputy behind the Red Mosque bloodbath," The Sunday Times, July 15, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Novikov, Evgenii. "A Russian agent at the right hand of bin Laden?" The Jamestown Foundation 2(1), January 15, 2004. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Osborne, Sean. "Ayman al-Zawahiri: Echoes of Alexander Litvinenko," Northeast Intelligence Network, May 6, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Pike, John. "Ayman al-Zawahiri," Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Porter, Gareth. "Gulf allies and 'Army of Conquest," Al-Ahram Weekly, May 28, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Preobrazhensky, Konstantin. "Russia and Islam are not Separate: Why Russia backs Al-Qaeda," The Centre for Counterintelligence and Security Studies, December 19, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Qutb, Sayed. Milestones. Islamic Book Service, 2006. ISBN 978-8172312442

- Raphaeli, Nimrod, "Ayman Muhammad Rabi' Al-Zawahiri: The Making of an Arch Terrorist," Terrorism and Political Violence 14(4), Winter 2002, 1–22.

- Riedel, Bruce O. The search for al Qaeda : its leadership, ideology, and future. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0815704522

- Roy, Olivier. and Antoine Sfeir (eds.). The Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0231131308

- Rubin, Barry. Islamic Fundamentalism in Egyptian Politics, 2nd Revised Edition, (London, UK and New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. ISBN 978-1349731305

- Rubin, Barry, and Judith Colp Rubin (eds.). Anti-American Terrorism and the Middle East: A Documentary Reader. Oxford, UK and New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0195176599

- Sageman, Marc. Understanding Terror Networks. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0812238082

- Schindler, John. "Exploring Al Qaeda's Murky Connection To Russian Intelligence," Business Insider, June 10, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Stroilov, Pavel. "Moscow's jihadi," The Spectator, June 25, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Soufan, Ali H., and Daniel Freedman. The Black Banners: 9/11 and the War against al-Qaeda. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2011. ISBN 978-0393079425

- Stack, Liam. Egypt Releases Brother of Al Qaeda's No. 2," The New York Times, March 17, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Tarek, Sherif. "Brother of Al-Qaeda's Zawahri re-arrested," Ahram Online, March 20, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Van Linschoten, Alex Strick, and Felix Kuehn. An Enemy We Created: The Myth of the Taliban-Al Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan. Oxford, UK and New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0199927319

- Vidino, Lorenzo. The New Muslim Brotherhood in the West. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0231151269

- Ward, Alexander, Nahal Toosi, and Lara Seligman. "U.S. kills Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahri in drone strike," Politico, August 1, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Watson, Eleanor. "Al-Zawahiri was on his Kabul balcony. How Hellfire missiles took him out," CBS News, August 2, 2011.

- Wilkinson, Isambard. "Al-Qa'eda chief Ayman Zawahiri attacks Pakistan's Pervez Musharraf in video," The Daily Telegraph, London, UK, August 11, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Wiktorowicz, Quintan. "A Genealogy of Radical Islam," Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 28(2), August 20, 2006, 75–97. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Wright, Lawrence, The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York, NY: Alfred Knopf, 2006. ISBN 037541486X

Further reading

- al-Zawahiri, Ayman. L'absolution, translated by Jean-Pierre Milleli, Paris, Éditions Milelli: 2008. (French translation of Al-Zawahiri's latest book).

- Ibrahim, Raymond. The Al Qaeda Reader. New York, NY: Broadway Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0767922623.

- Kepel, Gilles, and Jean-Pierre Milelli. Al Qaeda in its own words. Cambridge & London, Harvard University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0674028043.

- Mansfield, Laura. His Own Words: A Translation of the Writings of Dr. Ayman Al Zawahiri. Morrisville, NC: Lulu Pub, 2006. ISBN 978-1847288806

External links

All links retrieved September 18, 2022.

- Counter Extremism Project profile

- Tag Archives: Ayman al Zawahiri – Page 1

- Tag Archives: Ayman al Zawahiri – Page 2

- Tag Archives: Ayman al Zawahiri – Page 3

Statements and interviews

- Excerpts and video footage released 1 December 2005 from the September 2005 interview, MEMRI

- Al-Zawahiri Calls on Muslims to Give Aid to Earthquake Victims in Pakistan

- Letter from al-Zawahiri to al-Zarqawi, copy at GlobalSecurity.org

Articles

- The Man Behind Bin Laden, Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, September 16, 2002

- report on the al-Zarqawi video tape, CNN, January 2006

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.