Articles of Confederation

| Articles of Confederation | |

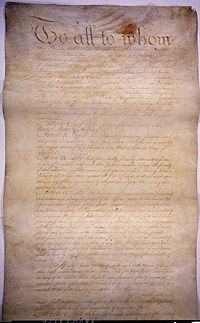

Page I of the Articles of Confederation

| |

| Created | November 15, 1777 |

| Ratified | March 1, 1781 |

| Location | |

| Authors | Continental Congress |

| Signers | Continental Congress |

| Purpose | Constitution for the United States, later replaced by the creation of the current United States Constitution |

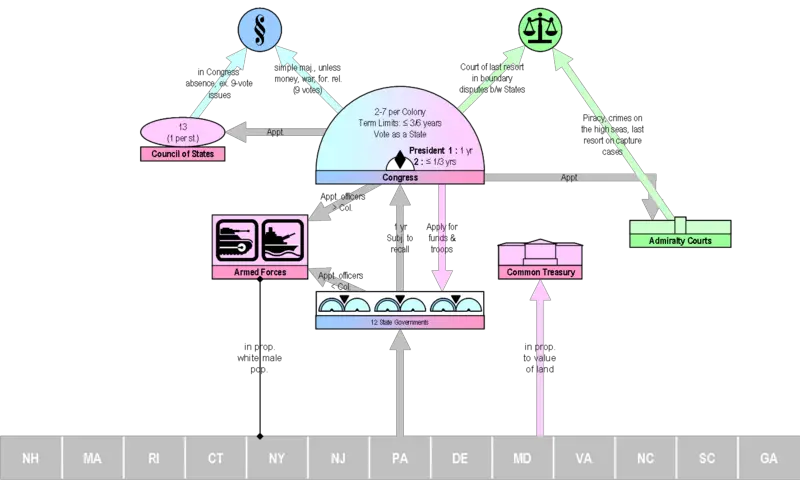

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union (commonly referred to as the Articles of Confederation) was the governing constitution of the alliance of thirteen independent and sovereign states styled "United States of America." The Article's ratification (proposed in 1777) was completed in 1781, legally uniting the states by compact into the "United States of America" as a union with a confederation government. Under the Articles (and the succeeding Constitution) the states retained sovereignty over all governmental functions not specifically deputed to the central government.

The Articles set the rules for operations of the "United States" confederation. The confederation was capable of making war, negotiating diplomatic agreements, and resolving issues regarding the western territories; it could not mint coins (each state had their own currency) and borrow inside and outside the United States. An important element of the Articles was that Article XIII stipulated that "their provisions shall be inviolably observed by every state" and "the Union shall be perpetual."

They sought a federation to replace the confederation. The key criticism by those who favored a more powerful central state (the federalists) was that the government (the Congress of the Confederation) lacked taxing authority; it had to request funds from the states. Also various federalist factions wanted a government that could impose uniform tariffs, give land grants, and assume responsibility for unpaid state war debts ("assumption".) Another criticism of the Articles was that they did not strike the right balance between large and small states in the legislative decision making process. Due to its one-state, one-vote plank, the larger states were expected to contribute more but had only one vote.

Fearing the return of a monarchical form of government, the system created by The Articles ultimately proved untenable. Their failure in creating a strong central government resulted in their replacement by the United States Constitution.

Background

The political push for the colonies to increase cooperation began in the French and Indian Wars in the mid 1750s. The opening of the American Revolutionary War in 1775 induced the various states to cooperate in seceding from the British Empire. The Second Continental Congress starting 1775 acted as the confederation organ that ran the war. Congress presented the Articles for enactment by the states in 1777, while prosecuting the American Revolutionary war against the Kingdom of Great Britain.

The Articles were created by the chosen representatives of the states in the Second Continental Congress out of a perceived need to have "a plan of confederacy for securing the freedom, sovereignty, and independence of the United States." Although serving a crucial role in the victory in the American Revolutionary War, a group of reformers,[1] known as "federalists," felt that the Articles lacked the necessary provisions for a sufficiently effective government.

The final draft of the Articles was written in the summer of 1777 and adopted by the Second Continental Congress on November 15, 1777 in York, Pennsylvania after a year of debate. In practice the final draft of the Articles served as the de facto system of government used by the Congress ("the United States in Congress assembled") until it became de jure by final ratification on March 1, 1781; at which point Congress became the Congress of the Confederation.

Ratification

Congress began to move for ratification of the Articles in 1777:

"Permit us, then, earnestly to recommend these articles to the immediate and dispassionate attention of the legislatures of the respective states. Let them be candidly reviewed under a sense of the difficulty of combining in one general system the various sentiments and interests of a continent divided into so many sovereign and independent communities, under a conviction of the absolute necessity of uniting all our councils and all our strength, to maintain and defend our common liberties…[2]

The document could not become officially effective until it was ratified by all of the thirteen colonies. The first state to ratify was Virginia on December 16, 1777.[3] The process dragged on for several years, stalled by the refusal of some states to rescind their claims to land in the West. Maryland was the last holdout; it refused to go along until Virginia and New York agreed to cede their claims in the Ohio River valley. A little over three years passed before Maryland's ratification on March 1, 1781.

Article summaries

Even though the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution were established by many of the same people, the two documents were very different. The original five-paged Articles contained thirteen articles, a conclusion, and a signatory section. The following list contains short summaries of each of the thirteen articles.

- Establishes the name of the confederation as "The United States of America."

- Asserts the precedence of the separate states over the confederation government, i.e. "Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated."

- Establishes the United States as a league of states united "…for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them …."

- Establishes freedom of movement–anyone can pass freely between states, excluding "paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice." All people are entitled to the rights established by the state into which he travels. If a crime is committed in one state and the perpetrator flees to another state, he will be extradited to and tried in the state in which the crime was committed.

- Allocates one vote in the Congress of the Confederation (United States in Congress Assembled) to each state, which was entitled to a delegation of between two and seven members. Members of Congress were appointed by state legislatures; individuals could not serve more than three out of any six years.

- Only the central government is allowed to conduct foreign relations and to declare war. No states may have navies or standing armies, or engage in war, without permission of Congress (although the state militias are encouraged).

- When an army is raised for common defense, colonels and military ranks below colonel will be named by the state legislatures.

- Expenditures by the United States will be paid by funds raised by state legislatures, and apportioned to the states based on the real property values of each.

- Defines the powers of the central government: to declare war, to set weights and measures (including coins), and for Congress to serve as a final court for disputes between states.

- Defines a Committee of the States to be a government when Congress is not in session.

- Requires nine states to approve the admission of a new state into the confederacy; pre-approves Canada, if it applies for membership.

- Reaffirms that the Confederation accepts war debt incurred by Congress before the Articles.

- Declares that the Articles are perpetual, and can only be altered by approval of Congress with ratification by all the state legislatures.

Still at war with the Kingdom of Great Britain, the colonists were reluctant to establish another powerful national government. Jealously guarding their new independence, members of the Continental Congress created a loosely-structured unicameral legislature that protected the liberty of the individual states. While calling on Congress to regulate military and monetary affairs, for example, the Articles of Confederation provided no mechanism to force the states to comply with requests for troops or revenue. At times, this left the military in a precarious position, as George Washington wrote in a 1781 letter to the governor of Massachusetts, John Hancock.

The End of the war

The Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended hostilities with Great Britain, languished in Congress for months because state representatives failed to attend sessions of the national legislature. Yet Congress had no power to enforce attendance. Writing to George Clinton in September 1783, George Washington complained:

Congress have come to no determination yet respecting the Peace Establishment nor am I able to say when they will. I have lately had a conference with a Committee on this subject, and have reiterated my former opinions, but it appears to me that there is not a sufficient representation to discuss Great National points.[4]

Function

The Articles supported the Congressional direction of the Continental Army, and allowed the 13 states to present a unified front when dealing with the European powers. As a tool to build a centralized war-making government, they were largely a failure: Historian Bruce Chadwick wrote:

George Washington had been one of the very first proponents of a strong federal government. The army had nearly disbanded on several occasions during the winters of the war because of the weaknesses of the Continental Congress. … The delegates could not draft soldiers and had to send requests for regular troops and militia to the states. Congress had the right to order the production and purchase of provisions for the soldiers, but could not force anyone to actually supply them, and the army nearly starved in several winters of war.[5][6]

Since guerrilla warfare was an effective strategy in a war against the British Empire, a centralized government proved unnecessary for winning independence. The Continental Congress took all advice, and heeded every command by George Washington, and thusly the government essentially acted in a federalist manner during the war, thereby hiding all problems of the Articles until the war was over.[7] Under the Articles, Congress could make decisions, but had no power to enforce them. There was a requirement for unanimous approval before any modifications could be made to the Articles. Because the majority of lawmaking rested with the states, the central government was also kept limited.

Congress was denied the power of taxation: it could only request money from the states. The states did not generally comply with the requests in full, leaving the Confederation Congress and the Continental Army chronically short of funds. Congress was also denied the power to regulate commerce, and as a result, the states maintained control over their own trade policy as well. The states and the national congress had both incurred debts during the war, and how to pay the debts became a major issue after the war. Some states paid off their debts; however, the centralizers favored federal assumption of states' debts.

Nevertheless, the Congress of the Confederation did take two actions with lasting impact. The Land Ordinance of 1785 established the general land survey and ownership provisions used throughout later American expansion. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 noted the agreement of the original states to give up western land claims and cleared the way for the entry of new states.

Once the war was won, the Continental Army was largely disbanded. A very small national force was maintained to man frontier forts and protect against Indian attacks. Meanwhile, each of the states had an army (or militia), and 11 of them had navies. The wartime promises of bounties and land grants to be paid for service were not being met. In 1783, Washington defused the Newburgh conspiracy, but riots by unpaid Pennsylvania veterans forced the Congress to leave Philadelphia temporarily.[8]

Signatures

The Second Continental Congress approved the Articles for distribution to the states on November 15, 1777. A copy was made for each state and one was kept by the Congress. The copies sent to the states for ratification were unsigned, and a cover letter had only the signatures of Henry Laurens and Charles Thomson, who were the President and Secretary to the Congress.

The Articles themselves were unsigned, and the date left blank. Congress began the signing process by examining their copy of the Articles on June 27, 1778. They ordered a final copy prepared (the one in the National Archives), directing delegates to inform the secretary of their authority for ratification.

On July 9, 1778, the prepared copy was ready. They dated it, and began to sign. They also requested each of the remaining states to notify its delegation when ratification was completed. On that date, delegates present from New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and South Carolina signed the Articles to indicate that their states had ratified. New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland could not, since their states had not ratified. North Carolina and Georgia also didn't sign that day, since their delegations were absent.

After the first signing, some delegates signed at the next meeting they attended. For example, John Wentworth of New Hampshire added his name on August 8. John Penn was the first of North Carolina's delegates to arrive (on July 10), and the delegation signed the Articles on July 21, 1778.

The other states had to wait until they ratified the Articles and notified their Congressional delegation. Georgia signed on July 24, New Jersey on November 26, and Delaware on February 12, 1779. Maryland refused to ratify the Articles until every state had ceded its western land claims.

On February 2, 1781, the much-awaited decision was taken by the Maryland General Assembly in Annapolis.[9] As the last piece of business during the afternoon Session, "among engrossed Bills" was "signed and sealed by Governor Thomas Sim Lee in the Senate Chamber, in the presence of the members of both Houses… an Act to empower the delegates of this state in Congress to subscribe and ratify the articles of confederation" and perpetual union among the states. The Senate then adjourned "to the first Monday in August next." The decision of Maryland to ratify the Articles was reported to the Continental Congress on February 12. The formal signing of the Articles by the Maryland delegates took place in Philadelphia at noon time on March 1, 1781 and was celebrated in the afternoon. With these events, the Articles entered into force and the United States came into being as a united, sovereign and national state.

Congress had debated the Articles for over a year and a half, and the ratification process had taken nearly three and a half years. Many participants in the original debates were no longer delegates, and some of the signers had only recently arrived. The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union were signed by a group of men who were never present in the Congress at the same time.

The signers and the states they represented were:

- New Hampshire: Josiah Bartlett and John Wentworth Jr.

- Massachusetts Bay: John Hancock, Samuel Adams, Elbridge Gerry, Francis Dana, James Lovell, and Samuel Holten

- Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: William Ellery, Henry Marchant, and John Collins

- Connecticut: Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, Oliver Wolcott, Titus Hosmer, and Andrew Adams

- New York: James Duane, Francis Lewis, William Duer, and Gouverneur Morris

- New Jersey: John Witherspoon and Nathaniel Scudder

- Pennsylvania: Robert Morris, Daniel Roberdeau, Jonathan Bayard Smith, William Clingan, and Joseph Reed

- Delaware: Thomas McKean, John Dickinson, and Nicholas Van Dyke

- Maryland: John Hanson and Daniel Carroll

- Virginia: Richard Henry Lee, John Banister, Thomas Adams, John Harvie, and Francis Lightfoot Lee

- North Carolina: John Penn, Cornelius Harnett, and John Williams

- South Carolina: Henry Laurens, William Henry Drayton, John Mathews, Richard Hutson, and Thomas Heyward Jr.

- Georgia: John Walton, Edward Telfair, and Edward Langworthy

Roger Sherman (Connecticut) was the only person to sign all four great state papers of the United States: the Articles of Association, the United States Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution.

Robert Morris (Pennsylvania) was the only person besides Sherman to sign three of the great state papers of the United States: the United States Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution.

John Dickinson (Delaware) and Daniel Carroll (Maryland), along with Sherman and Morris, were the only four people to sign both the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution.

Presidents of the Congress

The following list is of those who led the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation as the Presidents of the United States in Congress Assembled. Under the Articles, the president was the presiding officer of Congress, chaired the Cabinet (the Committee of the States) when Congress was in recess, and performed other administrative functions. He was not, however, a chief executive in the way the successor President of the United States is a chief executive, but all of the functions he executed were under the auspices and in service of the Congress.

- Samuel Huntington (March 1, 1781– July 9, 1781)

- Thomas McKean (July 10, 1781–November 4, 1781)

- John Hanson (November 5, 1781– November 3, 1782)

- Elias Boudinot (November 4, 1782– November 2, 1783)

- Thomas Mifflin (November 3, 1783– October 31, 1784)

- Richard Henry Lee (November 30, 1784– November 6, 1785)

- John Hancock (November 23, 1785– May 29, 1786)

- Nathaniel Gorham (June 6, 1786– November 5, 1786)

- Arthur St. Clair (February 2, 1787– November 4, 1787)

- Cyrus Griffin (January 22, 1788– November 2, 1788)

For a full list of Presidents of the Congress Assembled and Presidents under the two Continental Congresses before the Articles, see President of the Continental Congress.

Gallery

Legacy

Revision and replacement

In May 1786, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina proposed that Congress revise the Articles of Confederation. Recommended changes included granting Congress power over foreign and domestic commerce, and providing means for Congress to collect money from state treasuries. Unanimous approval was necessary to make the alterations, however, and Congress failed to reach a consensus. The weakness of the Articles in establishing an effective unifying government was underscored by the threat of internal conflict both within and between the states, especially after Shays' Rebellion threatened to topple the state government of Massachusetts.

In September, five states assembled in the Annapolis Convention to discuss adjustments that would improve commerce. Under their chairman, Alexander Hamilton, they invited state representatives to convene in Philadelphia to discuss improvements to the federal government. Although the states' representatives to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia were only authorized to amend the Articles, the representatives held secret, closed-door sessions and wrote a new constitution. The new Constitution gave much more power to the central government, but characterization of the result is disputed. Historian Forrest McDonald, using the ideas of James Madison from Federalist 39, describes the change this way:

The constitutional reallocation of powers created a new form of government, unprecedented under the sun. Every previous national authority either had been centralized or else had been a confederation of sovereign states. The new American system was neither one nor the other; it was a mixture of both.[10]

Patrick Henry, George Mason, and other antifederalists were not so eager to give up the local autonomy won by the revolution.

Antifederalists feared what Patrick Henry termed the "consolidated government" proposed by the new Constitution. They saw in Federalist hopes for commercial growth and international prestige only the lust of ambitious men for a "splendid empire" that, in the time-honored way of empires, would oppress the people with taxes, conscription, and military campaigns. Uncertain that any government over so vast a domain as the United States could be controlled by the people, Antifederalists saw in the enlarged powers of the general government only the familiar threats to the rights and liberties of the people.[11]

According to their own terms for modification (Article XIII), the Articles would still have been in effect until 1790, the year in which the last of the 13 states ratified the new Constitution. The Congress under the Articles continued to sit until November 1788,[12][13][14][15] overseeing the adoption of the new Constitution by the states, and setting elections. By that date, 11 of the 13 states had ratified the new Constitution.

Assessment

Historians have given many reasons for the perceived need to replace the articles in 1787. Jillson and Wilson (1994) point to the financial weakness as well as the norms, rules and institutional structures of the Congress, and the propensity to divide along sectional lines.

Rakove (1988) identifies several factors that explain the collapse of the Confederation. The lack of compulsory direct taxation power was objectionable to those wanting a strong centralized state or expecting to benefit from such power. It could not collect customs after the war because tariffs were vetoed by Rhode Island. Rakove concludes that their failure to implement national measures "stemmed not from a heady sense of independence but rather from the enormous difficulties that all the states encountered in collecting taxes, mustering men, and gathering supplies from a war-weary populace."[16] The second group of factors Rakove identified derived from the substantive nature of the problems the Continental Congress confronted after 1783, especially the inability to create a strong foreign policy. Finally, the Confederation's lack of coercive power reduced the likelihood for profit to be made by political means, thus potential rulers were uninspired to seek power.

When the war ended in 1783, certain special interests had incentives to create a new "merchant state," much like the British state people had rebelled against. In particular, holders of war scrip and land speculators wanted a central government to pay off scrip at face value and to legalize western land holdings with disputed claims. Also, manufacturers wanted a high tariff as a barrier to foreign goods, but competition among states made this impossible without a central government.[17]

Political scientist David C. Hendrickson writes that two prominent political leaders in the Confederation, John Jay of New York and Thomas Burke of North Carolina believed that "the authority of the congress rested on the prior acts of the several states, to which the states gave their voluntary consent, and until those obligations were fulfilled, neither nullification of the authority of congress, exercising its due powers, nor secession from the compact itself was consistent with the terms of their original pledges."[18]

Law professor Daniel Farber argues that there was no clear consensus on the permanence of the Union or the issue of secession by the Founders. Farber wrote:

What about the original understanding? The debates contain scattered statements about the permanence or impermanence of the Union. The occasional reference to the impermanency of the Constitution are hard to interpret. They might have referred to a legal right to revoke ratification. But they could equally have referred to an extraconstitutional right of revolution, or to the possibility that a new national convention would rewrite the Constitution, or simply to the factual possibility that the national government might break down. Similarly, references to the permanency of the Union could have referred to the practical unlikelihood of withdrawal rather than any lack of legal power. The public debates seemingly do not speak specifically to whether ratification under Article VII was revocable.[19]

However, what if one or more states do violate the compact? One view, not only about the Articles but also the later Constitution, was that the state or states injured by such a breach could rightfully secede. This position was held by, among others, Thomas Jefferson and John Calhoun.

If any state in the Union will declare that it prefers separation … to a continuance in union …. I have no hesitation in saying, let us separate.

Jefferson letter to James Madison, 1816

This view motivated discussions of secession and nullification at the Hartford Convention, the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, and the Nullification Crisis. In his book Life of Webster, (1890) Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge writes

It is safe to say that there was not a man in the country, from Washington and Hamilton to Clinton and Mason, who did not regard the new system as an experiment from which each and every State had a right to peaceably withdraw.[20][21]

A competing view, promoted by Daniel Webster and later by Abraham Lincoln , was that the Constitution (and Articles) established a permanent union.[22][23] President Andrew Jackson during the Nullification Crisis, in his “Proclamation to the People of South Carolina,” made the case for the perpetuity of the Union while also contrasting the differences between “revolution” and “secession”:[24]

But each State having expressly parted with so many powers as to constitute jointly with the other States a single nation, cannot from that period possess any right to secede, because such secession does not break a league, but destroys the unity of a nation, and any injury to that unity is not only a breach which would result from the contravention of a compact, but it is an offense against the whole Union. To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union, is to say that the United States are not a nation because it would be a solecism to contend that any part of a nation might dissolve its connection with the other parts, to their injury or ruin, without committing any offense. Secession, like any other revolutionary act, may be morally justified by the extremity of oppression; but to call it a constitutional right, is confounding the meaning of terms, and can only be done through gross error, or to deceive those who are willing to assert a right, but would pause before they made a revolution, or incur the penalties consequent upon a failure.[25]

This view, among others, was presented against declarations of secession from the Union by southern slave states as the American Civil War began.

See also

- History of the United States

- United States Declaration of Independence

- United States Constitution

- United States Bill of Rights

Notes

- ↑ "Its [the Philadelphia Convention's] official function was to propose revisions to the Articles. But the delegates, meeting in secret, quickly decided to draft a totally new document. Of the 55 delegates, only 8 had signed the Declaration of Independence. Most of the leading radicals, including Sam Adams, Patrick Henry, Paine, Lee, and Jefferson, were absent. In contrast, 21 delegates belonged to the militarist Society of the Cincinnati. Overall, the convention was dominated by the array of nationalist interests that the prior war had brought together: land speculators, ex-army officers, public creditors, and privileged merchants." Contrasting views presented by Jeffrey Rogers Hummel, William Marina, Did the Constitution Betray the Revolution?, The Independent Institute. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Monday, November 17, 1777, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. A Century of Lawmaking, 1774-1873 Library of Congress. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Articles of Confederation, 1777-1781. U.S. Department of State, accessdate November 18, 2008

- ↑ Letter George Washington to George Clinton, September 11, 1783. The George Washington Papers, 1741-1799 Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Bruce Chadwick. George Washington's War. (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2004. ISBN 9781402202223), 469.

- ↑ Glenn A. Phelps, "The Republican General" in George Washington Reconsidered, edited by Don Higginbotham. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001. ISBN 0813920051), 165-166. Phelps wrote:

- "It is hardly surprising, given their painful confrontations with a weak central government and the sovereign states, that the former generals of the Revolution as well as countless lesser officers strongly supported the creation of a more muscular union in the 1780s and fought hard for the ratification of the Constitution in 1787. Their wartime experiences had nationalized them."

- ↑ "While Washington and Steuben were taking the army in an ever more European direction, Lee in captivity was moving the other way – pursuing his insights into a full fledged and elaborated proposal for guerrilla warfare. He presented his plan to Congress, as a "Plan for the Formation of the American Army." Bitterly attacking Steuben's training of the army according to the "European Plan," Lee charged that fighting British regulars on their own terms was madness and courted crushing defeat: "If the Americans are servilely kept to the European Plan, they will … be laugh'd at as a bad army by their enemy, and defeated in every [encounter]… . [The idea] that a decisive action in fair ground may be risqued is talking nonsense." Instead, he declared that "a plan of defense, harassing and impeding can alone succeed," particularly if based on the rough terrain west of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. He also urged the use of cavalry and of light infantry (in the manner of Dan Morgan), both forces highly mobile and eminently suitable for the guerrilla strategy. This strategic plan was ignored both by Congress and by Washington, all eagerly attuned to the new fashion of Prussianizing and to the attractions of a "real" army." - Murray N. Rothbard, Generalissimo Washington: How He Crushed the Spirit of Liberty excerpted from Conceived in Liberty, Volume IV, chapters 8 and 41. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Henry Cabot Lodge, George Washington, Vol. I. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Friday, February 2, 1781, Laws of Maryland, 1781. An ACT to empower the delegates Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Forrest McDonald. Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1985. ISBN 9780700602841), 276

- ↑ Ralph Ketcham, Roots of the Republic: American Founding Documents Interpreted, 383.books.google.com. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Bobby Emory, "Chronology and Summary," The Articles of Confederation. Libertarian Nation Foundation, 1993. accessdate November 18, 2008

- ↑ Religion and the Congress of the Confederation, 1774-89 (Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, Library of Congress Exhibition) 2003-10-27. Library of Congress Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ [1] Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774-1789 - To Form a More Perfect Union: The Work of the Continental Congress & the Constitutional Convention (American Memory from the Library of Congress) Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ Jack N. Rakove, “The Collapse of the Articles of Confederation,” 225-245, in The American Founding: Essays on the Formation of the Constitution, Ed. by J. Jackson Barlow, Leonard W. Levy and Ken Masugi. (Greenwood Press. 1988. ISBN 0313256101), 230

- ↑ David C. Hendrickson. Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003. ISBN 9780700612376), 154

- ↑ Hendrickson, 153-154

- ↑ Daniel Farber. Lincoln's Constitution. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. ISBN 9780226237930), 87

- ↑ Lodge's view on the unanimity of this view is contested by Judge Caleb William Loring in UNION NOT MADE BY THE WAR The New York Times, February 12, 1893. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ↑ A textbook used at West Point before the Civil War, A View of the Constitution., written by Judge William Rawle in 1829, states in chapter XXXII, "The secession of a state from the Union depends on the will of the people of such state. The people alone as we have already seen, hold the power to alter their constitution. The Constitution of the United States is to a certain extent, incorporated into the constitutions or the several states by the act of the people. The state legislatures have only to perform certain organical operations in respect to it. To withdraw from the Union comes not within the general scope of their delegated authority. There must be an express provision to that effect inserted in the state constitutions. This is not at present the case with any of them, and it would perhaps be impolitic to confide it to them."

- ↑ This view, along with the view that the union was a binding contract from which no state could unilaterally remove itself, was included in Lincoln's First Inaugural Address.

- ↑ Thomas J. Pressly, “Bullets and Ballots: Lincoln and the ‘Right of Revolution’,” The American Historical Review 67 (3) (Apr., 1962): 649-650. In 1848 Lincoln expressed “unequivocal support for the ‘right of revolution,’" with the following comment regarding Mexico:

- Any people anywhere, being inclined and having the power, have the right to rise up, and shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better. This is a most valuable,-a most sacred right-a right, which we hope and believe, is to liberate the world. Nor is this right confined to cases in which the whole people of an existing government, may choose to exercise it. Any portion of such people that can, may revolutionize, and make their own, of so much of the teritory [sic] as they inhabit. More than this, a majority of any portion of such people may revolutionize, putting down a minority, intermingled with, or near about them, who may oppose their movement. Such minority, was precisely the case, of the tories of our own revolution. It is a quality of revolutions not to go by old lines, or old laws; but to break up both, and make new ones.

- ↑ Robert V. Remini. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833-1845. (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1984. ISBN 0060152796), 21

- ↑ President Jackson's Proclamation Regarding Nullification, December 10, 1832'. The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. accessdate November 18, 2008

References and Further Reading

- Bernstein, R. B. "Parliamentary Principles, American Realities: The Continental and Confederation Congresses, 1774-1789," 76-108, in Inventing Congress: Origins & Establishment Of First Federal Congress, ed. by Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon. Athens, OH: Published for the United States Capitol Historical Society by Ohio University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780821412718.

- Burnett, Edmund Cody. The Continental Congress: A Definitive History of the Continental Congress From Its Inception in 1774 to March, 1789. New York: Macmillan Co., 1941. OCLC 1467233.

- Chadwick, Bruce. George Washington's War. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2004. ISBN 9781402202223.

- Farber, Daniel. Lincoln's Constitution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. ISBN 9780226237930.

- Feinberg, Barbara. The Articles Of Confederation. Brookfield, CT: Twenty-First Century Books, 2002. ISBN 9780761321149.

- Hendrickson, David C., Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003. ISBN 9780700612376.

- Hoffert, Robert W. A Politics of Tensions: The Articles of Confederation and American Political Ideas. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1992. ISBN 9780870812545.

- Horgan, Lucille E. Forged in War: The Continental Congress and the Origin of Military Supply and Acquisition Policy. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002. ISBN 9780313013751.

- Jensen, Merrill. The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-Constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774-1781. University of Wisconsin Press, 1948. OCLC 498124

- Jensen, Merrill. "The Idea of a National Government During the American Revolution," Political Science Quarterly 58 (1943), 356-379. ISSN 0032-3195

- Jillson, Calvin, and Rick K. Wilson. Congressional Dynamics: Structure, Coordination, and Choice in the First American Congress, 1774-1789. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994. ISBN 9780804722933.

- Klos, Stanley L. President Who? Forgotten Founders. Pittsburgh: Evisum, Inc., 2004. ISBN 0975262750.

- Lodge, Henry Cabot. George Washington, by Henry Cabot Lodge. Vols. I. & II. Boston; New York, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1890. online, [2]. fullbooks.com. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- McDonald, Forrest. Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1985. ISBN 9780700602841.

- Mclaughlin, Andrew C. A Constitutional History of the United States. New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts [1935]. OCLC 2741516

- Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence..New York: Knopf: Distributed by Random House, Inc., 1997. ISBN 9780679454922.

- Main, Jackson T. Political Parties before the Constitution. University of North Carolina Press, 1974. ISBN 9780807811948.

- Phelps, Glenn A. "The Republican General" in George Washington Reconsidered, edited by Don Higginbotham. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001. ISBN 0813920051.

- Pressly, Thomas J., “Bullets and Ballots: Lincoln and the ‘Right of Revolution’,” The American Historical Review 67 (3) (Apr., 1962). ISSN 0002-8762

- Rakove, Jack N. The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress. New York: Knopf: Distributed by Random House, 1979. ISBN 9780394423708.

- Rakove, Jack N. “The Collapse of the Articles of Confederation,” 225-245, in The American Founding: Essays on the Formation of the Constitution, Ed. by J. Jackson Barlow, Leonard W. Levy and Ken Masugi. Greenwood Press. 1988. ISBN 0313256101.

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833-1845. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1984. ISBN 0060152796.

- Rothbard, Murray N. Conceived in Liberty (4 Volume Set) Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2000. ISBN 0945466269.

External links

All links retrieved August 16, 2023.

- Articles of Confederation and related resources, Library of Congress

- Today in History: November 15, Library of Congress

- United States Constitution Online - The Articles of Confederation

- The Articles of Confederation, Chapter 45 (see page 253) of Volume 4 of Conceived in Liberty by Murray Rothbard, in PDF format.

| ||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.