Difference between revisions of "Anthropometry" - New World Encyclopedia

m ({{Contracted}}) |

(Grammatical Edits) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| − | + | ||

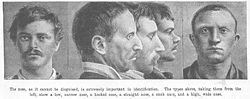

[[Image:The speaking portrait.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Illustration from "The Speaking Portrait" (Pearson's Magazine, Vol XI, January to June 1901) demonstrating the principles of Bertillon's anthropometry.]] | [[Image:The speaking portrait.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Illustration from "The Speaking Portrait" (Pearson's Magazine, Vol XI, January to June 1901) demonstrating the principles of Bertillon's anthropometry.]] | ||

| − | '''Anthropometry''' | + | '''Anthropometry''', or the "measure of humans", is derived from the Greek terms ανθρωπος, meaning man, and μετρον, meaning measure. The term physical anthropology refers to the measurement of living human individuals for the purposes of understanding human physical variation. |

| − | ==Bertillon | + | == Alphonse Bertillon == |

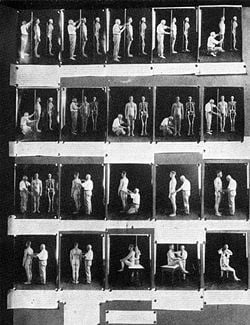

[[Image:Anthropometry exhibit.jpg|250px|thumb|right|Anthropometry demonstrated in an exhibit from a 1921 [[eugenics]] conference.]] | [[Image:Anthropometry exhibit.jpg|250px|thumb|right|Anthropometry demonstrated in an exhibit from a 1921 [[eugenics]] conference.]] | ||

| − | The French | + | The French savant, Alphonse Bertillon (b. 1853), coined the phrase physical anthropometry in 1883 to include an identification system based on unchanging measurements of the human frame. Through patient inquiry, Bertillon found that several physical features and dimensions of certain bony structures within the human body remained considerably unchanged throughout adulthood. |

| + | |||

| + | From this, Bertillon concluded that when recording these measurements systematically, a single individual could be perfectly distinguished from another. When the value of Bertillon’s discovery was fully realized, his system was quickly adapted into police methodology in aims of preventing false identifications and arrests. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This practice, adopting the name "Bertillonage", became widely popular and became internationally applied to the administration of justice in most civilized countries at the time. In 1883 the practice was introduced to the country of France, and was quickly credited with remarkable success. England’s adoption of the Bertillon system would soon follow. In 1894, a special committee based in Paris launched an investigation into the methodology used by the system and the results obtained. The investigation proved favorable, in particular regards to the use of structural measurements for primary classification. Despite its report, the committee recommended the adoption of a systematic "finger printing" program as suggested by Francis Galton, and already practiced in Bengal. | ||

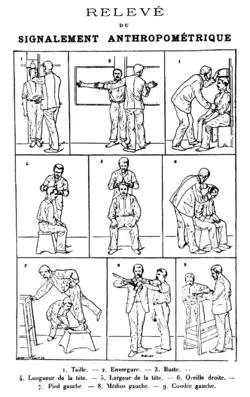

[[Image:Bertillon - Signalement Anthropometrique.png|right|thumb|250px|A chart from Bertillon's ''Identification anthropométrique'' (1893), demonstrating how to take measurements for his identification system.]] | [[Image:Bertillon - Signalement Anthropometrique.png|right|thumb|250px|A chart from Bertillon's ''Identification anthropométrique'' (1893), demonstrating how to take measurements for his identification system.]] | ||

| − | + | ==Measurement== | |

| − | + | Bertillon’s system divided the measurements into eleven categories including: height, stretch (as defined by the length of the body from left shoulder to right middle finger), bust (as defined by the length of one’s torso from the head to the seat, when seated), head width (measured from temple to temple), the length of one’s right ear, the length of one’s left foot, the length of one’s left middle finger, the length of one’s left cubit (or the extension from one’s elbow to the tip of one’s middle finger), the width of one’s cheeks and finally, the length of one’s little finger. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The accumulated details, first divided by the city of Paris into some 100,000 cards, allowed an official to sort specific measurements until the combined facts of details produced the certain individual sought. The system of information was contained in one cabinet designed to facilitate a search as efficiently as possible. Measurement records are without individual names, and final identification is achieved by means of a photograph attached to an individual's card of measurements. | |

| − | + | ==Anthropometry and Criminalistics== | |

| + | |||

| + | Anthropometry was first introduced in the late 19th century to the field of criminalistics, helping to identifying individual criminals by facial characteristics. Francis Galton, a key contributor to the field of criminalistics, would later find flaw with Bertillon’s system. Galton realized that variables originally believed independent, those of forearm length and leg length, could be combined into a single causal variable defined as stature. Galton, in realizing the redundancy of Bertillon’s measurements, had developed the statistical concept of correlation. | ||

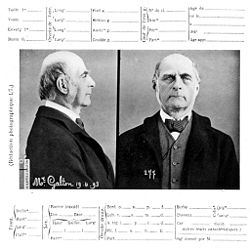

[[Image:Galton at Bertillon's (1893).jpg|right|thumb|250px|A Bertillon record for [[Francis Galton]], from a visit to Bertillon's laboratory in 1893.]] | [[Image:Galton at Bertillon's (1893).jpg|right|thumb|250px|A Bertillon record for [[Francis Galton]], from a visit to Bertillon's laboratory in 1893.]] | ||

| − | Bertillon's goal was to use anthropometry as a way of identifying | + | Alphonse Bertillon's goal was to use anthropometry as a way of identifying recidivists, or criminals likely to repeat their offense. Before the use of anthropometry, police officials relied solely on general descriptions and names to make arrests, and were unable to apprehend criminals employing false identities. Upon arrest, it was difficult to identify which criminals were first-time offenders and which were repeat offenders. Though the photographing of criminals had become common, it proved ineffectual as a system had not been found to visually arrange the photographs in a fashion that allowed easy use. Bertillon believed that through the use of anthropometry, all information about an individual criminal could be reduced to a set of identifying numbers which could then be entered into a large filing system. |

| − | Bertillon also | + | Bertillon also envisioned his system as being organized in such a way that if recorded measurements were limited, the system would still work to drastically reduce the number of potential matches through the categorizing of characteristics as either small, medium, or large. If the length of an individual’s arm was categorized as medium, and the size of the foot known, the number of potential records an official would compare with would be drastically reduced. Bertillon believed that with more measurements of independent variables, a more precise identification system could be achieved and paired with photographic evidence. Aspects of this philosophy would reappear in Francis Galton's development of systematic fingerprinting. |

| − | Anthropometry | + | ==Anthropometry and Fingerprinting== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==Anthropology | + | The use of Anthropometry in a criminological environment would eventually subside, overcome by the development of systematic finger printing. Bertillon’s system of measurements exhibited certain defects which would lead to its disregard. Objections to Bertillonage’s system often included the exorbitant costs of anthropometric instruments, the need for exceptionally trained employees, and the significant opportunity for error. |

| + | |||

| + | Measures taken or recorded with inaccuracy could seldom, if ever, be corrected, and would defeat all chance of a successful search. Bertillonage was also deemed slow, as it was necessary to repeat the anthropometrical process three times to arrive at a mean result. In 1897, Bertillonage was replaced throughout British India by the adoption of Bengal’s finger print system. Three years later England would follow suit. As the result of a fresh inquiry ordered by the Home Office, finger prints alone would be relied upon for identification. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Anthropometry and Anthropology== | ||

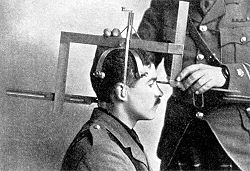

[[Image:Head-Measurer of Tremearne (side view).jpg|right|thumb|250px|A "head-measurer" tool designed for anthropological research in the early 1910s.]] | [[Image:Head-Measurer of Tremearne (side view).jpg|right|thumb|250px|A "head-measurer" tool designed for anthropological research in the early 1910s.]] | ||

| − | During the early 20th century, anthropometry was | + | During the early 20th century, anthropometry was extensively employed by anthropologists throughout the United States and Europe. A primary use of Anthropometry became the attempted differentiation between races of man. This study attempted to demonstrate in which ways certain races were superior to others. An application of intelligence testing was also incorporated into anthropometric study, and forms of anthropometry were used to advocate eugenics policies. During the 1920’s, members of Franz Boas’ School of Cultural Anthropology began to use anthropometric approaches to discredit the concept of fixed biological race. In later years, NAZI Germany would rely on anthropometric measurements to distinguish “Aryans” from Jews. These approaches were abandoned in the years following the Holocaust, and the teaching of physical anthropology went into general decline. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | During the 1940’s, William Sheldon employed anthropometry to evaluate somatotypes which accorded that characteristics of the body could be translated into characteristics of the mind. Sheldon also believed that one’s criminality could be predicted according to body type. Sheldon would run into considerable controversy when his work became public, relying extensively on photographs of nude Ivy League students for his studies. | |

| − | + | ==Modern Anthropometry== | |

| − | + | Today, anthropometric studies are conducted for various purposes. Academic anthropologists often investigate the evolutionary significance of varying physical proportions between populations stemming from ancestors of different environmental settings. Contemporary anthropometry has shown human populations to exhibit similar climatic variation to other large-bodied mammals. This finding is aligned with Bergmann's rule, stating that individuals in colder climates tend to be larger than individuals of warmer climates, and with Allen's rule, which states that individuals in cold climates will tend to have shorter, thicker limbs than those in warm climates. | |

| − | + | Anthropologists also use anthropometric variation to reconstruct small-scale population histories. In a study of 20th century Ireland, John Relethford's collection of anthropometric data exhibited geographical patterns of body proportions coinciding with historic invasions of Ireland by the English and the Norse. | |

| + | Aside from academia, scientists working for private companies and government agencies conduct anthropometric studies to determine the range of clothing sizes to be manufactured. Today, weight trainers often rely on basic anthropometric divisions, derived by Sheldon, for means of categorizing body type. Between 1945 and 1988, the United States Military conducted more than 40 anthropometric surveys of Military personnel, including a 1988 Army Anthropometric Survey (ANSUR) of members within its 240 measures. | ||

| − | Today | + | Today, technology is performing anthropometry with the use of three-dimensional scanners. A three-dimensional scan taken of an individual’s body allows anthropometric officials to extract measurements from the scan rather than directly from the individual. Officials can use this scan to extract any measurement at any time. |

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 68: | Line 63: | ||

* ''Report of Home Office Committee on the Best Means of Identifying Habitual Criminals'' (1893-1894) | * ''Report of Home Office Committee on the Best Means of Identifying Habitual Criminals'' (1893-1894) | ||

* [http://assist.daps.dla.mil/docimages/0000/40/29/54083.PD0 DOD-HDBK-743A], ''Anthropometry of US Military Personnel'' (1991) | * [http://assist.daps.dla.mil/docimages/0000/40/29/54083.PD0 DOD-HDBK-743A], ''Anthropometry of US Military Personnel'' (1991) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Resources== | ==Resources== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.humanics-es.com/recc-ergonomics.htm Ergonomics research: Anthropometrics, ergonomic tools, product design, etc.] | * [http://www.humanics-es.com/recc-ergonomics.htm Ergonomics research: Anthropometrics, ergonomic tools, product design, etc.] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit1|Anthropometry|55976194|}} | {{Credit1|Anthropometry|55976194|}} | ||

Revision as of 13:46, 17 July 2006

Anthropometry, or the "measure of humans", is derived from the Greek terms ανθρωπος, meaning man, and μετρον, meaning measure. The term physical anthropology refers to the measurement of living human individuals for the purposes of understanding human physical variation.

Alphonse Bertillon

The French savant, Alphonse Bertillon (b. 1853), coined the phrase physical anthropometry in 1883 to include an identification system based on unchanging measurements of the human frame. Through patient inquiry, Bertillon found that several physical features and dimensions of certain bony structures within the human body remained considerably unchanged throughout adulthood.

From this, Bertillon concluded that when recording these measurements systematically, a single individual could be perfectly distinguished from another. When the value of Bertillon’s discovery was fully realized, his system was quickly adapted into police methodology in aims of preventing false identifications and arrests.

This practice, adopting the name "Bertillonage", became widely popular and became internationally applied to the administration of justice in most civilized countries at the time. In 1883 the practice was introduced to the country of France, and was quickly credited with remarkable success. England’s adoption of the Bertillon system would soon follow. In 1894, a special committee based in Paris launched an investigation into the methodology used by the system and the results obtained. The investigation proved favorable, in particular regards to the use of structural measurements for primary classification. Despite its report, the committee recommended the adoption of a systematic "finger printing" program as suggested by Francis Galton, and already practiced in Bengal.

Measurement

Bertillon’s system divided the measurements into eleven categories including: height, stretch (as defined by the length of the body from left shoulder to right middle finger), bust (as defined by the length of one’s torso from the head to the seat, when seated), head width (measured from temple to temple), the length of one’s right ear, the length of one’s left foot, the length of one’s left middle finger, the length of one’s left cubit (or the extension from one’s elbow to the tip of one’s middle finger), the width of one’s cheeks and finally, the length of one’s little finger.

The accumulated details, first divided by the city of Paris into some 100,000 cards, allowed an official to sort specific measurements until the combined facts of details produced the certain individual sought. The system of information was contained in one cabinet designed to facilitate a search as efficiently as possible. Measurement records are without individual names, and final identification is achieved by means of a photograph attached to an individual's card of measurements.

Anthropometry and Criminalistics

Anthropometry was first introduced in the late 19th century to the field of criminalistics, helping to identifying individual criminals by facial characteristics. Francis Galton, a key contributor to the field of criminalistics, would later find flaw with Bertillon’s system. Galton realized that variables originally believed independent, those of forearm length and leg length, could be combined into a single causal variable defined as stature. Galton, in realizing the redundancy of Bertillon’s measurements, had developed the statistical concept of correlation.

Alphonse Bertillon's goal was to use anthropometry as a way of identifying recidivists, or criminals likely to repeat their offense. Before the use of anthropometry, police officials relied solely on general descriptions and names to make arrests, and were unable to apprehend criminals employing false identities. Upon arrest, it was difficult to identify which criminals were first-time offenders and which were repeat offenders. Though the photographing of criminals had become common, it proved ineffectual as a system had not been found to visually arrange the photographs in a fashion that allowed easy use. Bertillon believed that through the use of anthropometry, all information about an individual criminal could be reduced to a set of identifying numbers which could then be entered into a large filing system.

Bertillon also envisioned his system as being organized in such a way that if recorded measurements were limited, the system would still work to drastically reduce the number of potential matches through the categorizing of characteristics as either small, medium, or large. If the length of an individual’s arm was categorized as medium, and the size of the foot known, the number of potential records an official would compare with would be drastically reduced. Bertillon believed that with more measurements of independent variables, a more precise identification system could be achieved and paired with photographic evidence. Aspects of this philosophy would reappear in Francis Galton's development of systematic fingerprinting.

Anthropometry and Fingerprinting

The use of Anthropometry in a criminological environment would eventually subside, overcome by the development of systematic finger printing. Bertillon’s system of measurements exhibited certain defects which would lead to its disregard. Objections to Bertillonage’s system often included the exorbitant costs of anthropometric instruments, the need for exceptionally trained employees, and the significant opportunity for error.

Measures taken or recorded with inaccuracy could seldom, if ever, be corrected, and would defeat all chance of a successful search. Bertillonage was also deemed slow, as it was necessary to repeat the anthropometrical process three times to arrive at a mean result. In 1897, Bertillonage was replaced throughout British India by the adoption of Bengal’s finger print system. Three years later England would follow suit. As the result of a fresh inquiry ordered by the Home Office, finger prints alone would be relied upon for identification.

Anthropometry and Anthropology

During the early 20th century, anthropometry was extensively employed by anthropologists throughout the United States and Europe. A primary use of Anthropometry became the attempted differentiation between races of man. This study attempted to demonstrate in which ways certain races were superior to others. An application of intelligence testing was also incorporated into anthropometric study, and forms of anthropometry were used to advocate eugenics policies. During the 1920’s, members of Franz Boas’ School of Cultural Anthropology began to use anthropometric approaches to discredit the concept of fixed biological race. In later years, NAZI Germany would rely on anthropometric measurements to distinguish “Aryans” from Jews. These approaches were abandoned in the years following the Holocaust, and the teaching of physical anthropology went into general decline.

During the 1940’s, William Sheldon employed anthropometry to evaluate somatotypes which accorded that characteristics of the body could be translated into characteristics of the mind. Sheldon also believed that one’s criminality could be predicted according to body type. Sheldon would run into considerable controversy when his work became public, relying extensively on photographs of nude Ivy League students for his studies.

Modern Anthropometry

Today, anthropometric studies are conducted for various purposes. Academic anthropologists often investigate the evolutionary significance of varying physical proportions between populations stemming from ancestors of different environmental settings. Contemporary anthropometry has shown human populations to exhibit similar climatic variation to other large-bodied mammals. This finding is aligned with Bergmann's rule, stating that individuals in colder climates tend to be larger than individuals of warmer climates, and with Allen's rule, which states that individuals in cold climates will tend to have shorter, thicker limbs than those in warm climates.

Anthropologists also use anthropometric variation to reconstruct small-scale population histories. In a study of 20th century Ireland, John Relethford's collection of anthropometric data exhibited geographical patterns of body proportions coinciding with historic invasions of Ireland by the English and the Norse. Aside from academia, scientists working for private companies and government agencies conduct anthropometric studies to determine the range of clothing sizes to be manufactured. Today, weight trainers often rely on basic anthropometric divisions, derived by Sheldon, for means of categorizing body type. Between 1945 and 1988, the United States Military conducted more than 40 anthropometric surveys of Military personnel, including a 1988 Army Anthropometric Survey (ANSUR) of members within its 240 measures.

Today, technology is performing anthropometry with the use of three-dimensional scanners. A three-dimensional scan taken of an individual’s body allows anthropometric officials to extract measurements from the scan rather than directly from the individual. Officials can use this scan to extract any measurement at any time.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Lombroso, Antropometria di 400 delinquenti (1872)

- Roberts, Manual of Anthropometry (1878)

- Ferri, Studi comparati di antropometria (2 vols., 1881-1882)

- Lombroso, Rughe anomale speciali ai criminali (1890)

- Bertillon, Instructions signalétiques pour l'identification anthropométrique (1893)

- Livi, Anthropometria (Milan, 1900)

- Fürst, Indextabellen zum anthropometrischen Gebrauch (Jena, 1902)

- Report of Home Office Committee on the Best Means of Identifying Habitual Criminals (1893-1894)

- DOD-HDBK-743A, Anthropometry of US Military Personnel (1991)

Resources

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.