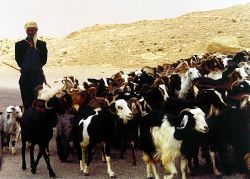

Animal husbandry

Animal husbandry, also known as animal science, is the agricultural practice of breeding and raising livestock. An outgrowth of agricultural practices and techniques of farmers for centuries, the commercialization of agriculture and the advances of veterinary science during the 20th century helped to establish a recognized scientific discipline that is taught in many universities and colleges and used all over the world.

History

Early agriculturists used animals extensively for labor, food, and raw material, but also realized, without the help of our modern understanding of genetics, that specific breeding practices could potentially yield more beneficial traits in animal offsprings. In earlier times, these people were usually herders of large stock, such as horses, deer, goats and sheep. Their methods of breeding were based solely on observable traits, so that animals with observably beneficial traits were bred, so that to produce offspring with combined traits.[1] Commonly this was achieved by pairing two desirable animals during times of female ovulation, and allowing the animals to breed on their own. However, since two healthy animals will not always breed on their own, artificial insemination was employed, first by the Arabs in 14th century. Others attempted similar techniques, particularly early European scientists interested in genetics[2] While these methods were sophisticated for the times they were used, they often produced mixed results.

In the 20th century, with the advent of genetic science, the manipulation of animal genes with the desired result of more advantageous offspring became more successful. By understanding the mechanics of genetic transmission from parent to offspring, scientists were able to breed animals in a more concise manner. Coupled with new advances in general veterinary science, nutrition and the commercialization of farms, animal husbandry became more systematic so as to yield higher quality animals, in shorter time frames and for less money.

Education

Animal husbandry and animal sciences are taught around the world in colleges and universities. Students of animal science sometimes go on to pursue degrees in veterinary medicine following graduation, or pursue master's degrees or doctorates in disciplines such as nutrition, genetics and breeding, or reproductive physiology. A strong demand for knowledge and experience in the science of breeding and raising animals in world wide agricultural markets helps graduates of these programs find work in the veterinary and human pharmaceutical industries, the livestock and pet supply and feed industries, or in academia.

Common Sub-Divisions of Animal Husbandry

Historically, animal husbandry is broken up into animal subdivisions, agriculturists tending to specialize on one or two types of animals. Below is a list and brief description of some of the major subdivisions:

- Swineherd: A person who cares for hogs and pigs (older English term: swine).

- Shepherd: Usually a person who cares for sheep. However, in previous years, it was common to have herds which were made up of both sheep and goats, in which case the term shepherd was still employed.

- goatherd: Someone who cares primarily for goats.

- cowherd/Cowboys: Refers to those who raise, milk and slaughter cattle. In more modern times, the cowboys or vaqueros of North and South America ride horses and participate in cattle drives to watch over cows and bulls raised primarily for food.

- Herder: a generic term for anyone who tends to a herd of animals not listed above, such as Camels, in Tibet yaks, and in Latin America, llamas and alpacas.

- Equestrian: A person who breeds and takes care of horses.

- Breeders: Generic term for anyone who specializes in the breeding of agricultural animals. More often, breeders are trained in specialized techniques, such as artificial insemination and embryo transfer, and are therefore independent hires of the usual farm staff.

Domestication

Domestication refers to the process of taming a population of animals (although it can also be used to refer to plants) or even a species as a whole. Humans have brought these populations under their care for a wide range of reasons: to produce food or valuable commodities (such as wool, cotton, or silk), for help with various types of work, transportation and to enjoy as pets or ornamental plants. Animals domesticated for home companionship are usually called pets while those domesticated for food or work are called livestock or farm animals.

Domestication of animals

According to evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond.[3], animal species must meet six criteria in order to be considered for domestication:

- Flexible diet — Creatures that are willing to consume a wide variety of food sources and can live off less cumulative food from the food pyramid (such as corn or wheat) are less expensive to keep in captivity. Most carnivores can only be fed meat, which requires the expenditure of many herbivores.

- Reasonably fast growth rate — Fast maturity rate compared to the human life span allows breeding intervention and makes the animal useful within an acceptable duration of caretaking. Large animals such as elephants require many years before they reach a useful size.

- Ability to be bred in captivity — Creatures that are reluctant to breed when kept in captivity do not produce useful offspring, and instead are limited to capture in their wild state. Creatures such as the panda and cheetah are difficult to breed in captivity.

- Pleasant disposition — Large creatures that are aggressive toward humans are dangerous to keep in captivity. The African buffalo has an unpredictable nature and is highly dangerous to humans. Although similar to domesticated pigs in many ways, American peccaries and Africa's warthogs and bushpigs are also dangerous in captivity.

- Temperament which makes it unlikely to panic — A creature with a nervous disposition is difficult to keep in captivity as they will attempt to flee whenever they are startled. The gazelle is very flighty and it has a powerful leap that allows it to escape an enclosed pen.

- Modifiable social hierarchy — Social creatures that recognize a hierarchy of dominance can be raised to recognize a human as its pack leader. Bighorn sheep cannot be herded because they lack a dominance hierarchy, whilst antelopes and giant forest hogs are territorial when breeding and cannot be maintained in crowded enclosures in captivity.[4]

Limits of domestication

A herding instinct arguably aids in domesticating animals: tame one and others will follow, regardless of chiefdom. Yet, despite long enthusiasm about revolutionary progress in farming, few crops and probably even fewer animals ever became domesticated.

Domesticated species, when bred for tractability, companionship or ornamentation rather than for survival, can often fall prey to disease: several sub-species of apples or cattle, for example, face extinction; and many dogs with very respectable pedigrees appear prone to genetic problems.

Domestication has also threatened humanity with disease. Cattle have given humanity various viral poxes, measles, and tuberculosis; pigs gave influenza; and horses the rhinoviruses. Humans share over sixty diseases with dogs. Many parasites also have their origins in domestic animals.

Ethical aspects of animal husbandry

There are contrasting views on the ethical aspects of breeding animals in captivity, with one debate being in relation to the merits of allowing animals to live in natural conditions reasonably close to those of their wild ancestors, compared to the view that considers natural pressures and stresses upon wild animals from disease, predation, and the like as vindication for captive breeding.

Some techniques of animal husbandry such as factory farming, tail docking, the Geier Hitch and castration, have been attacked by animal welfare groups as inhumane, unsanitary and counterproductive to the overall benefit of society.[5] Some of these practices also are criticized by farmers who use more traditional or organic practices. Genetic engineering is also controversial though it does not necessarily involve suffering. People who believe in animal rights generally oppose all forms of animal husbandry.[6]

Notes

- ↑ (2005) World of Genetics ["Animal Husbandry"] Retrieved September 17, 2007

- ↑ (2005) World of Invention ["Animal Breeding"] Retrieved September 17, 2007

- ↑ Diamond, Jared. "Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies" (Norton, 1999) ISBN 0393317552

- ↑ Diamond, Jared. "Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies" (Norton, 1999) ISBN 0393317552

- ↑ Guither, Harold D. "Animal Rights: History and Scope of a Radical Social Movement" (Souther Illinois University Press 1998) ISBN 0809321580

- ↑ (2007) PETA ["About PETA"] Retrieved September 19, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

External links

- Discussion of animal domestication

- Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond (ISBN 0-393-03891-2)

- News story about an early domesticated cat find

- Belyaev experiment with the domestic fox

- Use of Domestic Animals in Zoo Education

- The Initial Domestication of Cucurbita pepo in the Americas 10,000 Years Ago

- Phytolith evidence for early Holocene Cucurbita domestication in southwest Ecuador

- An Asian origin for a 10,000-year-old domesticated plant in the Americas

- Research Institute for Animal Husbandry

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

- In situ conservation of livestock and poultry, 1992, Online book, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the United Nations Environment Programme

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.