Andersonville prison

Template:Cleanup

| Andersonville National Historic Site | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Location: | Georgia, United States |

| Nearest city: | Americus, Georgia |

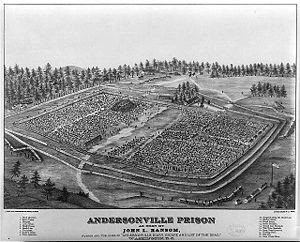

| Area: | 495 acres (2 km²) |

| Established: | April, 1864 |

| Visitation: | 132,466 (in 2005) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

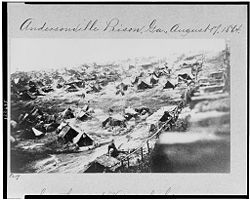

The Andersonville prison, located at Camp Sumter, was the largest Confederate military prison during the American Civil War. The site of the prison is now Andersonville National Historic Site in Andersonville, Georgia. It includes the site of the Civil War prison, the Andersonville National Cemetery, and the National Prisoner of War Museum. 12,913 Union prisoners died there, mostly of diseases.

History

Early in the Civil War prisoners were commonly paroled and sent home to await a formal exchange before they could return to active service. After an incident at Fort Pillow in Tennessee during which Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest's troops executed a group of black Union troops after their surrender, Union General Ulysses S. Grant voided that policy on the Union's part, and Federal authorities began to hold Confederate captives in formal prison camps rather than paroling them, until the Confederacy pledged to treat white and black Union soldiers alike. As result, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee refused this proposal and Confederate military and political leaders began to likewise construct prison camps to hold Union prisoners. Maj. Gen. Howell Cobb, former governor of Georgia, suggested the interior of that state as a possible location for these new camps since it was thought to be quite far from the front lines and would be relatively immune to Federal cavalry raids. A site was selected in Sumter County and the new prison opened in February 1864.

Because of the scarce resources of the Confederacy, Andersonville prison was frequently short of food, and even when this was sufficient in quantity, it was of a poor quality and poorly prepared on account of the lack of cooking utensils. The water supply, deemed ample when the prison was planned, became polluted under the congested conditions. During the summer of 1864, the prisoners suffered greatly from hunger, exposure, and disease, and in seven months about a third of them died from dysentery and were buried in mass graves, the usual procedure there. Many guards of Andersonville also died for the same reasons as the prisoners — however, it is highly debated whether these deaths were the same as the others or if they were from common factors in the American Civil War, such as trench foot.

At Andersonville, a light fence known as the deadline was erected approximately 19-25 feet (5.8-7.6 m) inside the stockade wall to demarcate a no-man's land keeping the prisoners away from the stockade wall. Anyone crossing this line was shot by sentries posted at intervals around the stockade wall.

The guards, disease, starvation, and exposure were not all that prisoners had to deal with. A group of prisoners, calling themselves the "Raiders," attacked their fellow inmates to steal food, jewelery, money, or even clothing. They were armed mostly with clubs, and even killed to get what they wanted. Several months later, another group rose up to stop the larceny, calling themselves "Regulators." They caught nearly all of the "Raiders" and these were tried by a judge (Peter "Big Pete" McCullough) and jury selected from a group of new prisoners. This jury upon finding the "Raiders" guilty set punishment upon them. These included running the gauntlet, being sent to the stocks, ball and chain, and, in six cases, hanging.[1]

In the autumn, after the capture of Atlanta, all the prisoners who could be moved were sent to Millen, Georgia, and Florence, South Carolina. At Millen, better arrangements prevailed, and when, after General William Tecumseh Sherman began his march to the sea, the prisoners were returned to Andersonville, the conditions there were somewhat improved.

During the war almost 45,000 prisoners were received at the Andersonville prison, and of these 12,913 died (40% of all the Union prisoners that died throughout the South).[2] A continual controversy among historians is the nature of the deaths and the reasons for it, with some contending that it was deliberate Confederate war crimes toward Union prisoners and others contending that it was merely the result of disease (promoted by severe overcrowding), the shortage of food in the Confederate States, the incompetence of the prison officials, and the refusal of the Confederate authorities to parole black soldiers, resulting in the imprisonment of soldiers from both sides, thus overfilling the stockade.

After the war, Henry Wirz, the superintendent, was tried by a court-martial featuring chief JAG prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman on charges of conspiracy and murder. On November 10, 1865 he was hanged. Wirz was the only prominent Confederate to have his trial heard and concluded (even the prosecution for Jefferson Davis dropped their case). The revelation of the sufferings of the prisoners was one of the factors that shaped public opinion regarding the South in the Northern states, after the close of the Civil War. The prisoners' burial ground at Andersonville has been made a national cemetery and contains 13,714 graves, of which 921 are marked "unknown".

In 1891 the Grand Army of the Republic, Department of Georgia bought the site of Andersonville Prison from membership and subscriptions from the North.[3] The site was purchased by the Federal Government in 1910.[4]

See also

- Reconstruction

- Camp Douglas (Chicago)

- Elmira Prison

- Johnson's Island

- Libby Prison

Notes

- ↑ "Andersonville:Prisoner of War Camp—Reading 2"http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/11andersonville/11facts2.htm

- ↑ National Park Service

- ↑ Roster and History of the Department of Georgia (States of Georgia and South Carolina) Grand Army of the Republic, Atlanta, Georgia: Syl. Lester & Co. Printers, 1894, 5.

- ↑ "Did You Know?" http://www.nps.gov/ande/historyculture/index.htm

Bibliography

- Chipman, The Horrors of Andersonville Rebel Prison (San Francisco, 1891)

- McElroy, Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons (Toledo, 1879)

- Spencer, A Narrative of Andersonville (New York, 1866)

- Stevenson, The Southern Side, or Andersonville Prison (Baltimore, 1876)

- Rhodes, History of the United States, volume v (New York, 1904), for an impartial account.

External links

- Andersonville Civil War Prison Historical Background

- Andersonville National Historic Site at NPS.gov

- See Andersonville: Prisoner of War Camp for a lesson on the prison camp from the National Park Service's Teaching with Historic Places.

- Andersonville Civil War Prison

- Maps and aerial photos

- Street map from Google Maps or Yahoo! Maps

- Topographic map from TopoZone

- Satellite image from Google Maps or Microsoft Virtual Earth

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.