Altar

An altar is a structure, like a table or platform, for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found in shrines, temples, churches, and other places built for worship. They are also found in homes, often for the purpose of venerating ancestors.

Altars continue to be used in Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, and modern paganism. Many historical-medieval faiths also made use of them, including the Roman, Greek, Norse, and other pagan religions, as well as in Judaism prior to the destruction of the Second Temple. They are used as places of prayer and worship and encounter with the deity.

Etymology

The modern English word altar was derived from Old English alter, from Latin altare (plural altaria) "high altar, altar for sacrifice to the great gods," perhaps originally meaning "burnt offerings" (compare Latin adolere "to worship, to offer sacrifice, to honor by burning sacrifices to"), but influenced by Latin altus "high."[1]

Purpose

The purpose and use of an altar is holy. Altars are places of worship and encounter with a deity or spirit, common to all faiths but particularly in paganism, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Judaism.[2]

An altar does not belong to any one religion or practice. An altar is a place to which one comes to honor the sacred by whatever name the sacred is perceived, and to deepen one’s experience of the latter. The purpose of an altar is to act as a window to the Divine — to open the channels of communication to the world of Spirit by virtue of the purity of its intention and the use to which it is put.[3]

Since sacrifices and offerings were made to deities, a place was required upon which the offering, perhaps food or incense, could be placed. The altar is a structure for the presentation of such religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. When the offering was a sacrifice, a structure had to be made on which the victim could be killed, blood channeled off, and possibly the flesh burned.

High places

High places are elevated areas on which altars were erected for worship in the belief that, as they were nearer heaven than the plains and valleys, they were more favorable places for prayer. High places were prevalent in almost all ancient cultures as centers of cultic worship.

High places in Israelite (Hebrew: Bamah, or Bamot) or Canaanite culture were open-air shrines, usually erected on an elevated site. Prior to the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites in the twelfth–eleventh century B.C.E., the high places served as shrines of the Canaanite fertility deities, the Baals (Lords) and the Asherot (Semitic goddesses). In addition to an altar, matzevot (stone pillars representing the presence of the divine) were erected, and sometimes a sacred tree.

The practice of worship on these spots became frequent among the Hebrews, though after the Temple of Jerusalem a movement against the use of high places developed. In the late sixth century B.C.E., King Josiah of Judah initiated a religious reform that destroyed some of the high places and attempted to bring local Levite priests who served at these sites to Jerusalem. Eventually, the Jerusalem Temple, itself a highly institutionalized high place, would be the only authorized place of sacrifice in the Jewish tradition.

Altars in antiquity

In antiquity, altars were so indispensable a part of the worship of the gods, that it seemed impossible to conceive of worship without them. For example, the ancient Celts in Europe practiced a form of paganism.[4] While little remains of the details since their societies were preliterate, it is believed that they worshiped numerous deities. Worship was conducted by druids in a sacred space, called a "nemeton" (plural nemeta), located outdoors, often in sacred groves of trees. They used stone altars and also sculpted images of various gods. When the Romans arrived, the poet Lucan wrote dramatically in his Pharsalia about these places of worship, such as the nemeton at Massilia (Marseilles):

No bird nested in the nemeton, nor did any animal lurk nearby; the leaves constantly shivered though no breeze stirred. Altars stood in its midst, and the images of the gods. Every tree was stained with sacrificial blood. The very earth groaned, dead yews revived; unconsumed trees were surrounded with flame, and huge serpents twined round the oaks. [5]

The Roman altar (Latin ara/arae pl.) was the most important feature of a temple. The ara stood outside of a temple building, usually in front of the steps. Next to the main altar were often erected smaller, temporary altars to “guest deities” associated with the deity who “owned” the temple. Altars were either square or round, with the latter form being less common. They were often decorated and bore an inscription with the name of the god to whom it was dedicated. Public religious ceremonies of the official Roman religion took place outdoors, and not within the temple building. Since the altars were used for sacrifices, this enabled the smoke from the burnt offering to ascend to the heavens.[6]

Two of the most famous altars in Roman history were the Ara Maxima, or Great Altar, dedicated to Hercules, and the Ara Pacis Augustae, or Altar of Augustan Peace, built in honor of Pax, personified Peace, and the “Augustan Peace” brought about by Augustus’ army.

Similarly, in Ancient Greece, altars were essential to worship and to the offering of sacrifices. The altars could be decorated elaborately, such as the Great Pergamon Altar which incorporated a sculptured frieze c.120 m. (130 yds.) long depicting the Olympian gods in battle with the Giants.[7]

In Rome as well as Greece, in addition to the altars attached to temples, many altars were placed in streets and squares, in the courts of houses, in open fields, in sacred groves, and other places consecrated to the gods.

Judaism

Altars in the Hebrew Bible were typically made of earth[8] or unwrought stone.[9] They were generally erected in conspicuous places .[10][11][12][13] The first altar recorded in the Hebrew Bible was erected by Noah.[14] Altars were also erected by Abraham,[15] by Isaac,[16] by Jacob,[17] and by Moses [18]

After the theophany on Mount Sinai, in the Tabernacle—and afterwards in the Temple—only two altars were used: The Altar of Burnt Offering, and the Altar of Incense, both near where the Ark of the Covenant was located.

The first Altar of Burnt Offering was made to be moved with the Children of Israel as they wandered through the wilderness. Its construction is described as square, five cubits in length and in breadth, and three cubits in height. It was made of shittim wood, and was overlaid with brass. In each of its four corners there were projections, called "horns" (keranot). The altar was hollow, except for a mesh grate which was placed inside halfway down, on which the wood sat for the burning of the sacrifices. The area under the grate was filled with earth. There were rings set on two opposite sides of the altar, through which poles could be placed for carrying it. These poles were also made of shittim wood and covered with brass.[19]

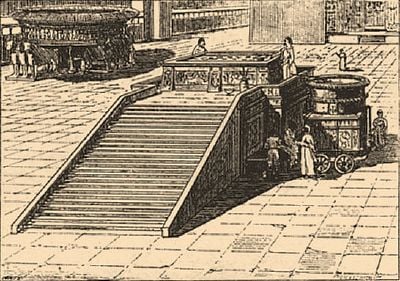

The description of the altar in Solomon's Temple gives it larger dimensions (2 Chronicles 4:1. Comp. 1 Kings 8:22, 1 Kings 8:64; 1 Kings 9:25), made wholly of brass, covering a structure of stone or earth. Because this altar was larger than the one used in the wilderness, it had a ramp leading up to it. A ramp was used because the use of steps to approach the altar was forbidden by the Torah: "Do not climb up to My altar with steps, so that your nakedness not be revealed on it."[20] On the day of the consecration of the new temple, Solomon also sanctified a space in the center of the Court of the Priests for burnt offerings, because the brazen altar he made was not large enough to hold all of the offerings.[21]

The second altar was the Altar of Incense (מִקְטַ֣ר miqṭar) (Exodus 30:1-10), also called the Golden Altar (מִזְבַּ֣ח הַזָּהָ֔ב mizbaḥ hazzāhāv) (Exodus 39:38; Numbers 4:11) and the Inner Altar (מִזְבַּ֣ח פְּנִימִי mizbaḥ pnimi). This was the indoor altar and stood in front of the Holy of Holies: "And thou shalt put it before the vail that is by the ark of the testimony, before the mercy seat that is over the testimony, where I will meet with thee."[22]

The remains of three rock-hewn altars were discovered in the Land of Israel: one below Tel Zorah, another at the foot of Sebastia (ancient Samaria), and a third near Shiloh.[23]

Christianity

The altar plays a central role in the celebration of the Eucharist, which takes place at the altar on which the bread and the wine for consecration are placed. All Christian Churches see the altar on which the Eucharist is offered as the "table of the Lord" (trapeza Kyriou) mentioned by Saint Paul.[24]

Altars occupy a prominent place in most Christian churches, both Eastern[25] and Western[26] branches. Commonly among these churches, altars are placed for permanent use within designated places of communal worship (often called "sanctuaries").

The area around the altar is seen as endowed with greater holiness, and is usually physically distinguished from the rest of the church, whether by a permanent structure such as an iconostasis, a rood screen, altar rails, a curtain that can be closed at more solemn moments of the liturgy (as in the Armenian Apostolic Church and Armenian Catholic Church), or simply by the general architectural layout. The altar is often on a higher elevation than the rest of the church.

Churches generally have a single altar, although in the Western branches of Christianity, as a result of the former abandonment of concelebration of Mass, so that priests always celebrated Mass individually, larger churches have had one or more side chapels, each with its own altar. The main altar was also referred to as the "high altar."

Architecturally, there are two types of altars: Those that are attached to the eastern wall of the chancel, and those that are free-standing and can be walked around, for instance when incensing the altar. When a free-standing altar is placed on the same floor-level as the congregation (in a cathedral, often at the "crossing") it is called a "low altar," particularly if the unused "high altar" is still in place, in the far end of the sanctuary.

When Christianity was legalized under Constantine the Great and Licinius, formal church buildings were built in great numbers, normally with free-standing altars in the middle of the sanctuary, which in all the earliest churches built in Rome was at the west end of the church:

When Christians in fourth-century Rome could first freely begin to build churches, they customarily located the sanctuary towards the west end of the building in imitation of the sanctuary of the Jerusalem Temple. Although in the days of the Jerusalem Temple the high priest indeed faced east when sacrificing on Yom Kippur, the sanctuary within which he stood was located at the west end of the Temple. The Christian replication of the layout and the orientation of the Jerusalem Temple helped to dramatize the eschatological meaning attached to the sacrificial death of Jesus the High Priest in the Epistle to the Hebrews.[27]

After the sixth century the contrary orientation prevailed, with the entrance to the west and the altar at the east end. Then the ministers and congregation all faced east during the whole celebration; and in Western Europe altars began, in the Middle Ages, to be permanently placed against the east wall of the chancel.

Less often than those placed in churches, though nonetheless notable, altars are set in spaces occupied less regularly, such as outdoors in nature, in cemeteries, in mausoleums or crypts, and family dwellings. Personal altars are those placed in a private bedroom, closet, or other space usually occupied by one person. They are used for practices of piety intended for one person (often referred to as a "private devotion").

Western Christian churches

In Western Christian churches, altars were free-standing so that the officiating bishop could circle the altar during the consecration of the church and its altar. When placed close to a wall or touching it, altars were often surmounted by a reredos—a large altarpiece, a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a church, often including religious images. With the increase in the size and importance of the reredos, most altars were built against the wall or barely separated from it. If free-standing, they could be placed, as also in Eastern Christianity, within a ciborium.

As well as altars in the structural sense, it became customary in the West to have portable altars, more commonly referred to as altar stones. When traveling, a priest could take one with him and place it on an ordinary table for saying Mass. They were also inserted into the center of structural altars especially those made of wood. In that case, it was the altar stone that was considered liturgically to be the altar.

Movable altars include the free-standing wooden tables without altar stone, placed in the choir away from the east wall, favored by churches in the Reformed tradition. Altars that not only can be moved but are repeatedly moved are found in low church traditions that do not focus worship on the Eucharist, celebrating it rarely. Both Catholics and Protestants celebrate the Eucharist at such altars outside of churches and chapels, as outdoors or in an auditorium.

Catholic Church

The Eastern Catholic Churches each follow their own traditions, which in general correspond to those of similar Eastern Orthodox or Oriental Orthodox Churches.

The Latin Church distinguishes between fixed altars (those attached to the floor) and movable altars (those that can be displaced):

It is desirable that in every church there be a fixed altar, since this more clearly and permanently signifies Christ Jesus, the Living Stone (1 Pt 2:4; cf. Eph 2:20). In other places set aside for sacred celebrations, the altar may be movable.[28]

The altar should be positioned so as to be the natural center of attention of the whole congregation, covered by at least one white cloth, and nothing else should be placed upon the altar table other than what is required for the liturgical celebration. A fixed altar should in general be topped by a slab of natural stone, thus conforming to tradition and to the significance attributed to the altar, but well-crafted solid wood is also permitted.[28]

In building new churches, it is preferable for a single altar to be erected, one that in the gathering of the faithful will signify the one Christ and the one Eucharist of the Church. In already existing churches, however, when the old altar is so positioned that it makes the people's participation difficult but cannot be moved without damage to artistic value, another fixed altar, skillfully made and properly dedicated, should be erected and the sacred rites celebrated on it alone. In order that the attention of the faithful not be distracted from the new altar the old altar should not be decorated in any special way.[28]

- Altars in Catholic churches

Protestant churches

A wide variety of altars exist in various Protestant denominations. Some Churches, such as the Lutheran, have altars very similar to Anglican or Catholic ones, in keeping with their more sacramental understanding of the Lord's Supper. Calvinist churches from Reformed, Baptist, Congregational, and Non-denominational backgrounds instead have a Communion Table adorned with a linen cloth, as well as an open Bible and a pair of candlesticks; it is not referred to as an altar because they do not see Holy Communion as sacrificial in any way.[29] Such a table may be temporary, and moved into place only when there is a Communion Service.

Some nondenominational churches have no altar or communion table, even if they retain the practice of the "altar call." [30] The altar call, whereby those who wish to make a new spiritual commitment to Jesus Christ are invited to come forward publicly, was invented by Methodist churches in the late seventeenth century and later picked up and popularized by Charles Finney in the mid-1800s — and the majority of evangelical churches use that form today. It is so named because the supplicants, at the end of the sermon, kneel at the altar rails, which are located below the pulpit platform.

Altars in Lutheran churches are often similar to those in Roman Catholic and Anglican churches. Lutherans believe that the altar represents Christ and should only be used to consecrate and distribute the Eucharist.[31] Lutheran altars are commonly made out of granite, but other materials are also used. A crucifix is placed above the altar.[31]

Altars in the Anglican Communion vary widely. In the Book of Common Prayer, the basis of doctrine and practice for the Church of England, there is no use of the specific word altar; the item in question is called the Lord's Table or Holy Table. However, common usage may call the communion table an altar.

Sensibilities concerning the sanctity of the altar are widespread in Anglicanism. In some parishes, the notion that the surface of the altar should only be touched by those in holy orders is maintained. In others, there is considerably less strictness about the communion table. Nonetheless, the continued popularity of communion rails in Anglican church construction suggests that a sense of the sanctity of the altar and its surrounding area persists. In most cases, moreover, the practice of allowing only those items that have been blessed to be placed on the altar is maintained (that is, the linen cloth, candles, missal, and the Eucharistic vessels).

- Altars in Protestant churches

High altar of St Paul's Cathedral, London

Eastern Christian Rites

Byzantine Rite

In the Byzantine tradition, what is called the “altar” is what would be called the “sanctuary” in the West, while what is called the altar in the West is called the Holy Table.[32] In an Eastern Orthodox or a Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic church the altar (sanctuary) therefore includes both the area behind the iconostasis, and the soleas (the elevated projection in front of the iconostasis), and the ambo.

For both Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Eastern Catholics, the Holy Table (altar) is normally free-standing, although in very small sanctuaries it might be placed flush against the back wall for reasons of space. They are typically about one meter high and square, made of stone or more commonly built out of wood. A plain linen covering is bound to the Holy Table with cords; this cover is never removed after the altar is consecrated, and is considered to be the "baptismal garment" of the altar. The linen covering symbolizes the winding sheet in which the body of Christ was wrapped when he was laid in the tomb. Above this cover is a second ornamented altar cloth (Indítia), often in a brocade of a liturgical color that may change with the ecclesiastical season. This outer covering usually comes all the way to the floor and represents the glory of God's Throne.[33]

Atop the altar is the tabernacle (Kovtchég), a miniature shrine sometimes built in the form of a church, inside of which is a small ark containing the reserved sacrament for use in communing the sick. Also kept on the altar is the Gospel Book. Under the Gospel is kept the antimension, a silken cloth imprinted with an icon of Christ being prepared for burial, which has a relic sewn into it and bears the signature of the bishop. Another, simpler cloth, the ilitón, is wrapped around the antimension to protect it, and symbolizes the "napkin" that was tied around the face of Jesus when he was laid in the tomb (forming a companion to the strachitsa).

The Holy Table may only be touched by ordained members of the higher clergy, namely bishops, priests, and deacons, and nothing which is not itself consecrated or an object of veneration should be placed on it. The Holy Table is used as the place of offering in the celebration of the Eucharist, where bread and wine are offered to God the Father and the Holy Spirit is invoked to make his Son Jesus Christ present in the Gifts. It is also the place where the presiding clergy stand at any service, even where no Eucharist is being celebrated and no offering is made other than prayer. When the priest reads the Gospel during Matins (or All-Night Vigil) on Sunday, he reads it standing in front of the Holy Table, because it represents the Tomb of Christ, and the Gospel lessons for Sunday Matins are always one of the Resurrection appearances of Jesus.

On the northern side of the sanctuary stands another, smaller altar, known as the Table of Oblation (Prothesis or Zhértvennik) at which the Liturgy of Preparation takes place. On it the bread and wine are prepared before the Divine Liturgy.

Oriental Rites

Altars in the various Oriental Rites are placed in the church, in various places.

For example, in the Armenian Rite the altar is placed against the eastern wall of the church, often in an apse. The shape of the altar is usually rectangular, similar to Latin altars, but is unusual in that it will normally have several steps on top of the table, on which are placed the tabernacle, candles, ceremonial fans, a cross, and the Gospel Book. The altar is often located upon a kind of stage above a row of icons.

On the other hand, altars in the Alexandrian (Coptic Orthodox Church) tradition must have a square face upon which to offer the sacrifice. As the standard Coptic liturgy requires the priest to encircle the altar, it is never attached to any wall. Most Coptic altars are located under a baldachin.

Hinduism

In Hinduism, altars generally contain pictures or statues of gods and goddesses. The word for temple is mandir (Sanskrit: मन्दिर), the altar as hypostatized temple. Any enclosure that which contains it, even an alcove or a small cabinet, is included as part of the altar, and shares its status as a temple in miniature. Large, ornate altars are found in Hindu temples while smaller altars are found in homes and sometimes also in Hindu-run shops and restaurants.

In South Indian temples, often each god will have his or her own shrine, each contained in a miniature house (specifically, a mandir). These shrines are often scattered around the temple compound, with the three main ones being in the main area. The statue of the god (murti) is placed on a stone pedestal in the shrine, and one or more lamps are hung in the shrine. There is usually a space to put the puja tray (tray with worship offerings). Directly outside the main shrine there will be a statue of the god's vahana or vehicle. The shrines have curtains hung over the entrances, and wooden doors which are shut when the deities are sleeping. Some South Indian temples have one main altar, with several statues placed upon it.

North Indian temples generally have one main altar at the front of the temple room. In some temples, the front of the room is separated with walls and several altars are placed in the alcoves. The statues on the altars are usually in pairs, each god with his consort (Radha-Krishna, Sita-Rama, Shiva-Parvati). However, some gods, such as Ganesha and Hanuman, are placed alone. Ritual items such as flowers or lamps may be placed on the altar.

Home altars are an intrinsic part of Hinduism. Since it is not practical to visit a temple frequently in order to offer prayers, a home altar allows for daily worship of the deities without hindrance.[34]

These home altars can be as simple or as elaborate as the householder can afford. Large, ornate shrines can be purchased in India and countries with large Hindu minorities, like Malaysia and Singapore. They are usually made of wood and have tiled floors for statues to be placed upon. Pictures may be hung on the walls of the shrine. The top of the shrine may have a series of levels, like a gopuram tower on a temple. Each Hindu altar will have at least one oil lamp and may contain a tray with puja equipment as well. Hindus with large houses will set aside one room as their puja room, with the altar at one end of it.[35]

Daoism

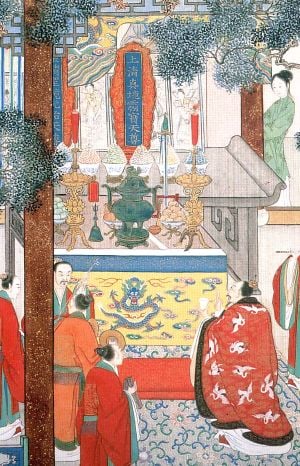

Daoist altars are erected to honor traditional deities and the spirits of ancestors. Altars may be erected in temples or in private homes. Imperial dynasties built huge altars called jìtán (祭坛) to perform various offering ceremonies called jìsì (祭祀). The Temple of Heaven in Beijing is one of those.

The altar traditionally has the following items[36]:

- Sacred lamp: symbolizing the light of Tao

- Two candles: representing the moon/Yin and sun/Yang

- Three cups: the union of the Yin and Yang

- Five plates of fruit: the five elements in their prenatal and postnatal form

- An incense burner: representing the lower abdominal area of the human body, where heat is produced

Nearly all forms of Chinese traditional religion involve baibai (拜拜)—bowing towards an altar, with a stick of incense in one's hand.[37] This may be done at home, or in a temple, or outdoors; by an ordinary person, or a professional (such as a Taoist priest); and the altar may feature any number of deities or ancestral tablets.

On certain dates, food may be set out as a sacrifice to the gods or spirits of the departed, such as for the Ghost Festival. In orthodox Daoist practice, the offerings should be incense, candles, and vegetarian offerings. Joss paper money may also be burned as it is believed to have value in the afterlife.

Shinto

In Japan, altars are found in Shinto shrines. Originating in ancient times, Himorogi (神籬, lit. "divine fence") are temporarily erected sacred spaces or "altars" used as a locus of worship. A physical area is demarcated with branches of green bamboo or sakaki tree at the four corners, between which are strung sacred border ropes (shimenawa). In the center of the area a large branch of sakaki festooned with sacred emblems (hei) is erected as a yorishiro, a physical representation of the presence of the kami (deity or spirit) and toward which rites of worship are performed.

Kamidana (神棚, lit. 'god/spirit-shelf') are miniature household altars provided to enshrine a Shinto kami. The kamidana is typically placed high on a wall and contains a wide variety of items related to Shinto-style ceremonies, the most prominent of which is the shintai, an object meant to house a chosen kami, thus giving it a physical form to allow worship. The kami within the shintai is often the deity of the local shrine or one particular to the house owner's profession. Worship at the kamidana typically consists of the offering of simple prayers, food (e.g., rice, fruit, water) and flowers.[38]

Buddhism

In Buddhist cultures, each temple has an altar, constructed as a sacred space to house images of the Buddha and his teachings. Offerings are placed on the altar as an expression of the practitioner’s devotion to the principle of enlightenment. It is also a place for deep meditation.[39]

In some Buddhist countries, structures such as bàn thờ, butsudan, or spirit houses are also found in homes. In Japan, the majority of homes have family altars, the Shinto kamidana and/or the Buddhist butsudan. The butsudan is very important for the family as it enshrines the ancestors who have died. If no-one has yet died in the family, they may not yet have a butsudan.[40]

The butsudan is a wooden cabinet with doors that enclose and protect the main religious image, the Honzon (本尊, "fundamental honored [one]") of the Buddha or the Bodhisattvas (typically in the form of a statue) or a mandala scroll, which is installed in the highest place of honor. The doors are opened to display the image during religious observances.[41]

A butsudan usually contains subsidiary religious items—called butsugu—such as candlesticks, incense burners, bells, and platforms for placing offerings such as fruit; the butsudan may be decorated with flowers. Some sects place memorial tablets for deceased ancestors, within or near the butsudan. Zen Buddhists also meditate before the butsudan.

The original design for the butsudan began in India, where people built altars as an offering-place to the Buddha. When Buddhism came to China and Korea statues of the Buddha were placed on pedestals or platforms. The Chinese and Koreans built walls and doors around the statues to shield them from the weather and also adapted elements of their respective indigenous religions. They could then safely offer their prayers, incense, and offerings to the statue or scroll without it falling and breaking.[42]

Norse paganism

A basic altar, called a hörgr, was used for sacrifice in Norse paganism. The hörgr was constructed outdoors, made of piled stones, and would be used in sacrifices and as a place to privately worship and consult with the divine.[43]

Sacred spaces were generally constructed outside the homes:

The earliest enclosures for sacred spaces appear to have consisted of an earthwork or ditch to mark off the area in which worship or special rites took place. Such enclosures might be square, rectangular or circular in shape, and might contain such features as ritual shafts, springs, hearths, pillars, standing stone or monoliths.[44]

A possible use of the hörgr during a sacrifice would be to place upon it a bowl of the blood of an animal sacrificed to a Norse deity, such as a goat for Thor, a sow for Freyja, or boar for Freyr. Then a bundle of fir twigs would be dipped into the blood and sprinkled over the participants. This would consecrate the attendees to the ceremony, such as a wedding.[45]

In Nordic Modern Pagan practice, altars may be set up in the home or in wooded areas in imitation of the hörgr of ancient times. They may be dedicated to Thor, Odin, or other Nordic deities.

Neopaganism

In neopaganism there is a wide variety of ritual practice, running the gamut from a very eclectic syncretism to strict polytheistic reconstructionism. Many of these groups make use of altars. Some are constructed merely of rough-hewn or stacked stone, and some are made of fine wood or other finished material.

Wicca

Wiccan practitioners use altars to place several symbolic and functional items for the purpose of worshiping the God and Goddess, casting spells, and/or saying chants and prayers. Wiccan altars may be set up outside as well as indoors.

The altar is often considered a personal place where practitioners put their ritual items. Some practitioners may keep various religious items upon the altar, or they may use the altar and the items during their religious workings. In the center of the altar are kept the main symbols of the Wiccan faith, such as the pentacle. Items representing the feminine, the Goddess, and the male, the God, are placed on the left and right sides.[46]

There are eight Wiccan holidays, known as Sabbats, that celebrate the cycles and seasons of nature. The major Sabbats are Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh: the Cross-Quarter days; The minor Sabbats are Yule (Winter Solstice), Ostara (Spring Equinox), Litha (Summer Solstice), and Mabon (Autumn Equinox). Based on the Sabbat, the altar is decorated accordingly. For example, the Summer Solstice altar cloth should be white and the altar decorated with summer flowers, fruits, and anything else that symbolizes summer.[47]

Neo-Druidism

Modern Neo-Druidism may also make use of altars, often erected in groves. Though little is known of the specific religious beliefs and practices presided over by the ancient Druids, modern people who identify themselves as Druids are free to incorporate their imagination in developing ceremonies and the use of ritual objects in keeping with their belief system.

Druids create altars for various reasons:

First, an altar is a dedicated space for an outward expression of your internal spiritual journey. If you engage in daily meditation or other activity, or for when you are doing ritual work, its useful to have a space to visit. Its also good to have a place to put objects of significance, such as stones or feathers, and it can be added to as you go about your spiritual path.[48]

Druids often dedicate a shelf, mantle, or table, or small space indoors as their altar. However, altars can be erected outside, often using stones or other natural materials.[49]

Notes

- ↑ altar Etymology Online. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ↑ Altar use in Judaism is historical only: It ended with the destruction of the Second Temple.

- ↑ GurujiMa, Beginning a Spiritual Practice, Part II: Creating an Altar Light Omega. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ↑ Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition (Academy Chicago Publishers, 2005, ISBN 978-0897334358).

- ↑ Yowann Byghan, Modern Druidism: An Introduction (McFarland, 2018, ISBN 978-1476673141).

- ↑ William Smith, Ara A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (John Murray, London, 1875). Retrieved May 4 2024.

- ↑ Karin E. Christiaens, The Pergamon Altar Smart History. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ↑ Exodus 20:24 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Exodus 20:25 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Genesis 22:9 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Ezekiel 6:3 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ 2 Kings 23:12 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ 2 Kings 16:4, 2 Kings 23:8 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Genesis 8:20 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Genesis 12:7, Genesis 13:4, Genesis 22:9 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Genesis 26:25 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Genesis 33:20, Genesis 35:1-3 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Exodus 17:15 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Exodus 27:1-8 Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ↑ Exodus 20:26 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 7:7 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Exodus 30:6 Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ↑ Yael Elitzur and Doran Nir-Zevi, A Rock-Hewn Altar Near Shiloh Palestine Exploration Quarterly 135(1) (2013): 30–36. Retrieve May 5, 2024.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 10:21 Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ↑ Here "eastern" means Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Assyrian Church of the East, and the Ancient Church of the East; perhaps others.

- ↑ Here "western" means the Roman Catholic Church, churches of the Anglican Communion, Lutherans, and some Reformed; perhaps others.

- ↑ Helen Dietz, The Eschatological Dimension of Church Architecture: The Biblical Roots of Church Orientation Sacred Architecture Journal 10 (2005). Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 General Instruction of the Roman Missal United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ↑ Michael Keene, Christian Churches (Nelson Thornes, 2001, ISBN 978-0748752881).

- ↑ Harvey Cox, Fire From Heaven: The Rise Of Pentecostal Spirituality And The Reshaping Of Religion In The 21st Century (Da Capo Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0306810497).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 S. Anita Stauffer, Altar Guild and Sacristy Handbook (Augsburg Fortress, 2014, ISBN 978-1451478099).

- ↑ The Byzantine Altar New Liturgical Movement, October 25, 2005. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ↑ Isabel Florence Hapgood, Service Book of the Holy Orthodox-Catholic Apostolic Church (Independently published, 2019, ISBN 978-1701389496).

- ↑ Why do we have an Altar at home? Eshwar Bhakti. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ↑ The Home Shrine Hinduism Today, January 1, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ↑ Elizabeth Reninger, The Taoist Altar Learn Religions, June 25, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ↑ Brock Silvers, The Taoist Manual: An Illustrated Guide Applying Taoism to Daily Life (Honolulu, HI: Sacred Mountain Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0967794815).

- ↑ Brian Bocking, A Popular Dictionary of Shinto (Routledge, 2017, ISBN 978-1138155466).

- ↑ Tibetan Buddhist Altar The Newark Museum of Art. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ↑ Ian Reader, Esben Andreasen, and Finn Stefansson, Japanese Religions: Past and Present (University of Hawaii Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0824815462).

- ↑ John S. Harding, Studying Buddhism in Practice (Routledge, 2011, ISBN 978-0415464864).

- ↑ Mami Suzuki, What is a Butsudan? Tofugu, June 24, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ↑ Celeste Larsen, What Did Norse Pagan Altars and Sacred Spaces Look Like? Mage by Moonlight, July 30, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ↑ H.R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0815624417).

- ↑ Courtship, Love and Marriage in Viking Scandinavia The Viking Answer Lady. Retrieved May 9, 024.

- ↑ Scott Cunningham, Living Wicca: A Further Guide for the Solitary Practitioner (Llewellyn Publications, 2002, ISBN 978-0875421841).

- ↑ Raymond Buckland, Buckland's Complete Book of Witchcraft (Llewellyn Publications, 2002, ISBN 978-0875420509).

- ↑ Dana O'Driscoll, A Druid’s Indoor Altar / Shrine – Seasonal, Elemental, and Spirit The Druids Garden, January 3, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ↑ Dana O'Driscoll, Building Outdoor Sacred Spaces The Druids Garden, September 21, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bocking, Brian. A Popular Dictionary of Shinto. Routledge, 2017. ISBN 978-1138155466

- Buckland, Raymond. Buckland's Complete Book of Witchcraft. Llewellyn Publications, 2002. ISBN 978-0875420509

- Byghan, Yowann. Modern Druidism: An Introduction. McFarland, 2018. ISBN 978-1476673141

- Cox, Harvey. Fire From Heaven: The Rise Of Pentecostal Spirituality And The Reshaping Of Religion In The 21st Century. Da Capo Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0306810497

- Cunningham,Scott. Living Wicca: A Further Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. Llewellyn Publications, 2002. ISBN 978-0875421841

- Davidson, H.R. Ellis. Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0815624417

- Hapgood, Isabel Florence. Service Book of the Holy Orthodox-Catholic Apostolic Church. Independently published, 2019 (original 1922). ISBN 978-1701389496

- Harding, John S. Studying Buddhism in Practice. Routledge, 2011. ISBN 978-0415464864

- Keene, Michael. Christian Churches. Nelson Thornes, 2001. ISBN 978-0748752881

- Reader, Ian, Esben Andreasen, and Finn Stefansson. Japanese Religions: Past and Present. University of Hawaii Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0824815462

- Ross, Anne. Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition. Academy Chicago Publishers, 2005. ISBN 978-0897334358

- Silvers, Brock. The Taoist Manual: An Illustrated Guide Applying Taoism to Daily Life. Honolulu, HI: Sacred Mountain Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0967794815

- Stauffer, S. Anita. Altar Guild and Sacristy Handbook. Augsburg Fortress, 2014. ISBN 978-1451478099

- This article incorporates text from the public domain 1907 edition of The Nuttall Encyclopædia.

- This entry incorporates text from the public domain Easton's Bible Dictionary, originally published in 1897.

External links

All links retrieved

- Altars (in Scripture) Catholic Encyclopedia

- History of the Christian altar Catholic Encyclopedia

- Altar Bible Study Tools

- All about the Altar Briana Saussy

- Hinduism: Home Altar The Pluralism Project

- The Taoist Altar Learn Religions

- Altar Jewish Encyclopedia

- The Wiccan Altar My Book of Shadows

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.