Difference between revisions of "Zheng He" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) (import from wiki) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) m |

||

| (21 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| + | :''For the [[Three Kingdoms]] general, see [[Zhang He]].'' | ||

| + | [[Image:ZhengHeShips.gif|thumb|250px|Early [[seventeenth century]] Chinese [[woodblock]] print, thought to represent Zheng He's ships.]] | ||

| + | '''Zheng He''' ({{zh-tspw|t=鄭和|s=郑和|p=Zhèng Hé|w=Cheng Ho}}; Birth name: 馬三寶 / 马三宝; {{zh-p|p=Mǎ Sānbǎo}}; [[Islamic]] name: حجّي محمود شمس ''Hajji Mahmud Shams'') (1371–1433), was a [[China|Chinese]] mariner, [[exploration|explorer]], [[diplomat]] and fleet [[admiral]], who made the voyages collectively referred to as the travels of "''Eunuch Sanbao to the Western Ocean''" (Chinese: 三保太監下西洋)<ref>[http://www.qsn365.com/qsn365/articles/11260 三保太監下西洋]. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> or "''Zheng He to the Western Ocean,''" from 1405 to 1433. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

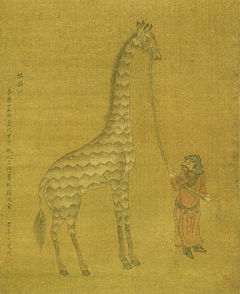

| + | As a young boy, Zheng He was taken captive by the [[Ming Dynasty|Ming]] and made a [[eunuch]] in the imperial service. He became a close confidant of the [[Yongle Emperor]]. Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He commanded a series of seven naval expeditions sponsored by the Ming government to establish a Chinese presence and extend the tributary system to the maritime nations in [[Southeast Asia]]. Zheng He set sail on his first voyage on July 11, 1405, commanding 62 treasure ships, 190 smaller ships and 27,800 men. At each port, Zheng He demanded that the inhabitants submit to the “Son of Heaven” (''tianzi,'' the Chinese Emperor), and rewarded those who cooperated with gifts. Zheng He brought back emissaries from 36 countries who agreed to a tributary relationship, along with rich and unusual gifts, including African [[zebra]]s and [[giraffe]]s that ended their days in the [[Ming]] imperial zoo. Zheng He died during the seventh voyage and was buried at sea off the [[Malabar]] coast near [[Calicut]] in Western India. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Life== | ==Life== | ||

| − | Zheng He was born in 1371 of the [[Hui people|Hui ethnic group]] | + | Zheng He was born in 1371 of the [[Hui people|Hui ethnic group]] in [[Kunyang]] (昆阳), [[Jinning]] (晋宁), modern-day [[Yunnan Province]] (雲南),<ref>[http://english.people.com.cn/data/minorities/Hui.html The Hui ethnic minority] - [[People's Daily]], ''People's Daily'' Online. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref><ref>[http://exhibitions.nlb.gov.sg/zhenghe/activities.html] Zheng He Exhibitions at Singapore National Library. National Library Board, Singapore. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> one of the last possessions of the [[Mongols]] of the [[Yuan Dynasty]] before being conquered by the [[Ming Dynasty]]. According to his biography in the [[History of Ming]], he was originally named Ma Sanbao (Ma Ho; 馬三保). Zheng belonged to the [[Semu]] or Semur caste which practiced [[Islam]]. He was a sixth-generation descendant of [[Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar]], a famous [[Khwarezmian language|Khwarezmian]] Yuan governor of Yunnan Province from [[Bukhara]] in modern day [[Uzbekistan]]. His family name "Ma" came from Shams al-Din's fifth son Masuh (Mansour). Both his father Mir Tekin and grandfather Charameddin had traveled on the [[hajj]], the Islamic pilgrimage to [[Mecca]], and their travels contributed much to the young boy's education. |

| + | |||

| + | In 1381, following the fall of the [[Yuan Dynasty]], a [[Ming Dynasty|Ming]] army was dispatched to Yunnan to put down the [[Mongols|Mongol]] rebel [[Basalawarmi]], commonly known as the Prince of Liang, a descendant of [[Kublai Khan]] and a Yuan Dynasty loyalist. Zheng He, then only a young boy of eleven years, was taken captive by that army and [[castration|castrated]], becoming a [[eunuch]]. He was made an orderly in the army, and by 1390, when the army was placed under the command of the Prince of Yen, Zheng He (Ma Ho) had distinguished himself as a junior officer, skilled in war and diplomacy. He became a close confidant of Prince of Yen. In 1400, the Prince of Yen revolted against his nephew, the Jianwen (Chien-wen) Emperor (建文帝; the second Emperor of the Ming dynasty, personal name Zhu Yunwen), and took the throne in 1402 as the Yongle Emperor]] (永楽帝) of [[China]] (reigned 1403–1424, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty). The [[Yongle emperor]] conferred the name ''Zheng He'' as a reward for his support in the Yongle rebellion against the [[Jianwen Emperor]] (建文帝 ). Zheng He studied at [[Nanjing Taixue]] (The Imperial Central College). | ||

| + | The Ming court then sought to display its naval power to the maritime states of South and Southeast Asia. The Chinese had been expanding their influence across the seas for three hundred years, establishing an extensive sea trade to bring spices and raw materials to China. Chinese travelers visited foreign nations, and Indian and Muslim visitors had widened China’s geographical horizons. By the beginning of the Ming dynasty, shipbuilding and the art of [[navigation]] had reached new heights in China. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming government sponsored a series of seven naval expeditions. Emperor Yongle intended them to establish a Chinese presence, impose imperial control over trade, and impress foreign peoples in the Indian Ocean basin. He also might have wanted to extend the tributary system, by which Chinese dynasties traditionally recognized foreign peoples. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Zheng He was selected by the Yongle Emperor to be commander in chief of the missions to the “Western Oceans.” He set sail on his first voyage on July 11, 1405, commanding 62 treasure ships and 27,800 men. Many of these ships were mammoth nine-masted "[[treasure ships]]," by far the largest marine craft the world had ever seen. The fleet visited Annan, Champa (now South Vietnam), Siam, Malacca, and Java; then sailed through the [[Indian Ocean]] to Calicut, Cochin, and Ceylon (now [[Sri Lanka]]), returning to China in 1407. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On his second voyage, in 1409, Zheng He (Cheng Ho) encountered hostility from King [[Alagonakkara]] of [[Ceylon]]. He defeated his forces and took the King back to [[Nanking]] as a captive to apologize to the Emperor. In 1411, Zheng He (Cheng Ho) set out on his third voyage, sailing to Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. On his return he touched at Samudra, on the northern tip of [[Sumatra]]. | ||

| + | Zheng He set out on his fourth voyage in 1413. After stopping at the principal ports of Asia, he proceeded westward from India to [[Hormuz]]. A part of the fleet then cruised southward down the Arabian coast, the [[Persian Gulf]] and [[Arabia]], visiting Djofar and Aden. A Chinese mission visited [[Mecca]] and continued to Egypt. The fleet visited Brava and Malindi in what is now [[Kenya]], and almost reached the Mozambique Channel. On his return to China in 1415, Cheng Ho brought envoys from more than 30 states of South and Southeast Asia to pay homage to the Chinese emperor. | ||

| + | During Zheng He (Cheng Ho)'s fifth voyage (1417–1419), the Ming fleet revisited the [[Persian Gulf]] and the east coast of Africa. In 1421, a sixth voyage was launched to return the foreign emissaries to their homes, again visiting Southeast Asia, [[India]], Arabia, and [[Africa]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Final Voyage== | ||

| + | In 1424, the Yongle Emperor died. His successor, the [[Hongxi Emperor]] (reigned 1424–1425), decided to curb Zheng He’s influence at court and appointed him garrison commander in [[Nanking]]. Zheng He made one final voyage under the [[Xuande Emperor of China|Xuande Emperor]] (reigned 1426–1435), visiting the states of Southeast Asia, the coast of India, the Persian Gulf, the [[Red Sea]], and the east coast of Africa, but after that the Chinese treasure ship fleets were disbanded. Zheng He died during the treasure fleet's last voyage. Although he has a tomb in China, it is empty: he was, like many great admirals, [[buried at sea]].<ref>[http://www.mariner.org/exploration/index.php?type=explorersection&id=57 The Seventh and Final Grand Voyage of the Treasure Fleet], ''The Mariners' Museum''. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The records of Zheng He's last two voyages, which were believed to have been his farthest, were unfortunately destroyed by the [[Ming Dynasty|Ming]] emperor. Therefore it can never be ascertained exactly where Zheng sailed on these two expeditions. The traditional view is that he went as far as [[Iran|Persia]]. It is now the widely accepted view that his expeditions went as far as the [[Mozambique Channel]] in East Africa, from the ancient Chinese artifacts discovered there. | |

| − | + | ==International Relations== | |

| + | [[Image:Yongle-Giraffe1.jpg|thumb|right|240px|An African [[giraffe]] being led into a Ming Dynasty [[zoo]].]] | ||

| + | [[Image:MalindiGiraffe.jpg|thumb|240px|A [[giraffe]] brought from [[Africa]] in the twelfth year of Yongle (1414 C.E.)]] | ||

| − | + | At each port, Zheng He demanded that the inhabitants submit to the “Son of Heaven” (''tianzi,'' the Chinese Emperor), and rewarded those who cooperated with gifts. Throughout his travels, Zheng He liberally dispensed Chinese gifts of [[silk]], [[porcelain]], and other goods. In return, he received rich and unusual presents from his hosts, including African [[zebras]] and [[giraffes]] that ended their days in the [[Ming]] imperial zoo. Zheng He and his company paid respects to local [[deities]] and customs, and in Ceylon they erected a monument honoring [[Buddha]], [[Allah]], and [[Vishnu]]. | |

| − | + | Ultimately, 36 countries in what the Chinese called the “Western Ocean” agreed to a tributary relationship with China. Zheng He generally sought to attain his goals through diplomacy, and his large army awed most would-be enemies into submission. But a contemporary reported that Zheng He "walked like a tiger," and did not shrink from violence when he considered it necessary to impress foreign peoples with China's military might. He ruthlessly suppressed pirates who had long plagued Chinese and southeast Asian waters. He also intervened in a civil disturbance in order to establish his authority in Ceylon, and he made displays of military force when local officials threatened his fleet in Arabia and east Africa. From his fourth voyage, he brought envoys from 30 states who traveled to China and paid their respects at the Ming court. | |

| − | |||

| − | Zheng He was | + | ==Legacy== |

| + | Zheng He’s missions were impressive demonstrations of organizational capability and technological advancement, but did not lead to significant trade, since Zheng He was an admiral and an official, not a merchant. Chinese merchants continued to trade in Japan and southeast Asia, but Imperial officials gave up any plans to maintain a Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean, and even destroyed most of the nautical charts that Zheng He had carefully prepared. Their motivations were political; during much of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), the eunuchs exercised great power in the imperial court, at the expense of the Confucian civil bureaucracy. The expeditions of Zheng He, who was himself a eunuch, were strongly supported by eunuchs in the court and bitterly opposed by the Confucian scholar bureaucrats.<ref>Richard Gunde, [http://www.international.ucla.edu/article.asp?parentid=10387 Zheng He's Voyages of Discovery], Berkeley: The Regents of the University of California. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | During the 1950s, historians including [[John Fairbank]] and [[Joseph Needham]] popularized the idea that after Zheng's voyages, China turned away from the seas and underwent a period of technological stagnation. Most current historians of China question the accuracy of this view, pointing out that Chinese maritime commerce did not stop after Zheng He, and that active Chinese trading with India and East Africa continued long after the time of Zheng and Chinese ships continued to dominate Southeast Asian commerce until the nineteenth century. The travels of the Chinese ''[[Junk Keying|Junk Keying]]'' to the [[United States]] and [[England]] between 1846 and 1848 testify to the power of Chinese shipping. Historians such as [[Jack Goldstone]] argue that the Zheng He voyages ended for practical reasons that did not reflect the technological level of China<ref>Jack A. Goldstone, [http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/10/114.html The Rise of the West—or Not?]. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> Starting in the early fifteenth century, China experienced increasing pressure from resurgent [[Mongolia]]n tribes from the north. In 1421 the emperor [[Yongle]] (the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty) moved his capital north from [[Nanjing]] to present-day [[Beijing]], from where, at considerable expense, China launched annual military expeditions to weaken the Mongolians. These land campaigns and a massive expansion of the [[Great Wall of China]] took precedence over state-sponsored naval explorations. | |

| − | Zheng He | + | ===Zheng He's tomb and museum=== |

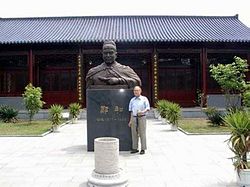

| + | [[Image:Zheng He's tomb, Nanjing.jpg|thumb|250px|Zheng He's tomb, [[Nanjing]]]][[Image:Museum in honour of Zheng He in Nanjing.jpg|left|thumb|250px|Museum in honor of Zheng He, Nanjing]]. | ||

| + | Zheng He's tomb in [[Nanjing]] has been repaired and a small museum has been built next to it. The tomb is empty as he was buried at sea off the [[Malabar]] coast near [[Calicut]] in Western India. However, his sword and other personal possessions were interred in a typical Muslim tomb inscribed with Arabic characters. [[Image:Statue of Zheng He with great great grandnephew.jpg|thumb|250px|Direct descendant of Wenming, Zheng He's elder brother, next to Zheng He's statue.]] | ||

| − | + | ===Zheng He as a Chinese Muslim=== | |

| + | Zheng He travelled to [[Mecca]], though he did not perform the pilgrimage itself. The government of the [[People's Republic of China]] uses him as a model to integrate the Muslim minority into the Chinese nation. | ||

| − | Zheng He, | + | Zheng He was a living example of [[religious tolerance]], perhaps even [[syncretism]], or at least a master of diplomacy. The [[Galle Trilingual Inscription]] set up by Zheng He around 1410 in [[Sri Lanka]] records the offerings he made at a [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] mountain. "Inscriptions written in Chinese, Tamil and Persian praise Buddha, Shiva and Allah in equal measure."<ref>Alex Perry |

| + | [http://www.time.com/time/asia/features/journey2001/india_sb1.html A Testament to an Odyssey, A Monument to a Failure Set in stone: Sri Lanka]. ''TIME'' Asia, August 2001, 158 (781). Retrieved January 15, 2008.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Around 1431, he set up a commemorative pillar at the temple of the [[Daoism|Daoist]] [[goddess]] [[Tian Fei]], the [[Celestial Spouse]], in [[Fujian]]( 福建) province, to whom he and his sailors prayed for safety at sea.<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/sultan/explorers2.html Ancient Chinese Explorers], NOVA Online. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> This pillar records his veneration for the goddess and his belief in her divine protection, as well as a few details about his voyages.<ref>[http://www.hist.umn.edu/hist1012/primarysource/source.htm Zheng He's Inscription], the ''Regents of the University of Minnesota''. excerpt from the book, ''Teobaldo Filesi,'' David Morison (trans.) ''China and Africa in the Middle Ages.'' (London: Frank Cass, 1972), 57-61. | |

| + | Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote><p>We have traversed more than 100,000 [[Li (Chinese unit)|li]] (50,000 kilometers) of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising in the sky, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds day and night, continued their course [as rapidly] as a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare…</p> | ||

| + | <p>—(Tablet erected by Zheng He, [[Changle]], [[Fujian]], 1432. Louise Levathes</p></blockquote> | ||

==Voyages== | ==Voyages== | ||

[[Image:KangnidoMap.jpg|thumb|300px|The [[Kangnido map]] (1402) predates Zheng's voyages and suggests that he had quite detailed geographical information on much of the [[Old World]].]] | [[Image:KangnidoMap.jpg|thumb|300px|The [[Kangnido map]] (1402) predates Zheng's voyages and suggests that he had quite detailed geographical information on much of the [[Old World]].]] | ||

| − | + | <table> | |

{|class="wikitable" | {|class="wikitable" | ||

! width=20% | Order | ! width=20% | Order | ||

| Line 51: | Line 78: | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| − | + | == Size of Zheng He’s Ships == | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == Size of | ||

=== Ancient chronicles === | === Ancient chronicles === | ||

| − | '''Treasure ship''' is the name of a type of [[ship|vessel]] that the [[China|Chinese]] [[admiral]] Zheng He sailed in. His fleet included 62 treasure ships, with some said to have reached 600 [[foot (unit)|feet]] (146 [[meter]]s) long. The fleet was manned by over 27,000 crew members, including [[navigator]]s, [[explorer]]s, [[sailor]]s, [[physician|doctors]], [[manual labor|workers]], and [[soldier]]s | + | '''Treasure ship''' is the name of a type of [[ship|vessel]] that the [[China|Chinese]] [[admiral]] Zheng He sailed in. His fleet included 62 treasure ships, with some said to have reached 600 [[foot (unit)|feet]] (146 [[meter]]s) long. The fleet was manned by over 27,000 crew members, including [[navigator]]s, [[explorer]]s, [[sailor]]s, [[physician|doctors]], [[manual labor|workers]], Muslim teachers, and [[soldier]]s. |

| − | |||

| − | According to ancient Chinese sources, Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. | + | According to ancient Chinese sources, Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. The 1405 expedition consisted of 27,800 men and a fleet of 62 treasure ships supported by approximately 190 smaller ships.<ref>Edward L. Dreyer. ''Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming, 1405–1433.''(London: Longman, 2006), 122–124</ref><ref>[http://www.chinaculture.org/gb/en_focus/2005-07/05/content_70352.htm Briton charts Zheng He's course across globe], ''Ministry of Culture, P.R. China''. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> The fleet included: |

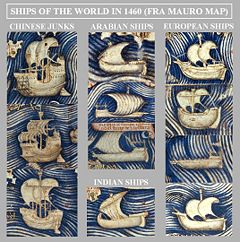

| − | [[Image:WorldShips1460.jpg|thumb|Ships of the world in 1460, according to the [[Fra Mauro map]]. Chinese junks are described as very large, three or four-masted ships.]] | + | [[Image:WorldShips1460.jpg|thumb|240px|Ships of the world in 1460, according to the [[Fra Mauro map]]. Chinese junks are described as very large, three or four-masted ships.]] |

The dimensions of the Zheng He's ships according to ancient Chinese chronicles and disputed by modern scholars (see below): | The dimensions of the Zheng He's ships according to ancient Chinese chronicles and disputed by modern scholars (see below): | ||

| − | * '''"[[Treasure ship]]s"''', used by the commander of the fleet and his deputies (nine-masted, about 126.73 [[ | + | * '''"[[Treasure ship]]s"''', used by the commander of the fleet and his deputies (nine-masted, said to be about 126.73 [[meter]]s (416 [[Foot (unit of length)|ft]]) long and 51.84 meters (170 ft) wide), according to later writers. The great size of these ships was probably exaggerated by later writers. The treasure ships purportedly weighed as much as 1,500 tons.126.73m by 51.84 m (415.780ft by 170.078ft)<ref>Zhang. ''"History of the Ming dynasty"'' («明史»), [[Zhang Tingyu]] chief editor, (originally published 1737), (“四十四丈一十八丈”)</ref> <ref>"Eunuch Sanbao's Journey to the Western Seas" («三宝太监西洋通俗演义记»),[[Luo Maodeng]], (originally published 1597), (“宝船长四十四丈四,阔一十八丈,每只船上有九道桅。”)</ref> By way of comparison, a modern ship of about 1,200 tons is 60 [[meters]] (200 ft) long [http://www.fcca.demon.co.uk/Flowernum.htm], and the ships [[Christopher Columbus]] sailed to the New World in 1492 were about 70-100 tons and 17 meters (55 ft) long.<ref>Keith A. Pickering.[http://www.columbusnavigation.com/ships.shtml Columbus's Ships]. ''www.columbusnavigation.com''. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> |

| − | * '''"[[Horse ships]]"''', carrying tribute goods and repair material for the fleet (eight-masted, about 103 m (339 ft) long and 42 m (138 ft) wide).<ref | + | * '''"[[Horse ships]]"''', carrying tribute goods and repair material for the fleet (eight-masted, about 103 m (339 ft) long and 42 m (138 ft) wide).<ref>Zhang, 1737 </ref> |

| − | * '''"[[Supply ships]]"''', containing staple for the crew (seven-masted, about 78 m (257 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) wide).<ref | + | * '''"[[Supply ships]]"''', containing staple for the crew (seven-masted, about 78 m (257 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) wide).<ref>Zhang, 1737</ref> |

| − | * '''"[[Troop transports]]"''', six-masted, about 67 m (220 ft) long and 25 m (83 ft) wide).<ref | + | * '''"[[Troop transports]]"''', six-masted, about 67 m (220 ft) long and 25 m (83 ft) wide).<ref>Zhang, 1737</ref> |

| − | * '''"[[Fuchuan warships]]"''', five-masted, about 50 m (165 ft) long).<ref | + | * '''"[[Fuchuan warships]]"''', five-masted, about 50 m (165 ft) long).<ref>Zhang, 1737</ref> |

| − | * '''"[[Patrol boats]]"''', eight-oared, about 37 m (120 feet) long).<ref | + | * '''"[[Patrol boats]]"''', eight-oared, about 37 m (120 feet) long).<ref>Zhang, 1737</ref> |

| − | * '''"[[Water tankers]]"''', with 1 month supply of fresh water. 126.73 m by 51.84 m (415.780ft by 170.078ft)<ref | + | * '''"[[Water tankers]]"''', with 1 month supply of fresh water. 126.73 m by 51.84 m (415.780ft by 170.078ft)<ref>Zhang, 1737</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Six more expeditions took place, from 1407 to 1433, with fleets of comparable size.<ref>Dreyer, 2006</ref> | |

=== Modern scholarship === | === Modern scholarship === | ||

| − | The dimensions of the treasure | + | The dimensions of the treasure ships, as recorded in later historical chronicles, are disputed by scholars. It is probable that the actual size of the ships was smaller, since in later historical periods wooden ships approaching this size (such as [[HMS Orlando (1858)|HMS ''Orlando'']]) were unwieldy and visibly undulated with the waves, even with steel braces in the hull. The problem of "hogging," the tendency of the [[largest wooden ships]] to sag (like a [[pig]]'s body) because of buoyancy in the middle, would have been impossible to solve. The length-to-width ratio of 2.47 is not well suited for fast navigation on the oceans. Hydrodynamic models have proved that ships with such dimension are unsailable in open seas. |

| − | Recent research suggests that the actual length of the biggest treasure ships may have lain between 59 m and 84 m.<ref>Sally K. Church | + | Recent research suggests that the actual length of the biggest treasure ships may have lain between 59 m and 84 m.<ref>Sally K. Church, "The Colossal Ships of Zheng He: Image or Reality?" (155-176);and "Zheng He; Images & Perceptions," in ''South China and Maritime Asia'' Volume 15, Hrsg: Roderich Ptak, Thomas O. Höllmann, (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag, 2005)</ref> If the treasure ships actually had the dimensions attributed to them, they would have been several times larger than any wooden ship ever recorded, including the largest ''l'Orient'' (65 m long). The length of the treasure ships would have been equivalent to that of the first generation aircraft carriers in the early twentieth century. Research on the original source of these dimensions indicates that they came from a novel written in the sixteenth century. <ref>For debates of these dimensions, see Chinese articles in [http://proj.ncku.edu.tw/chengho/ National Cheng Kung University] at National Cheng Kung University of Taiwan. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> |

| − | === Accounts of | + | === Accounts of Medieval Travelers === |

The characteristics of the Chinese ships of the period are described by Western travelers to the East, such as [[Ibn Battuta]] and [[Marco Polo]]. According to Ibn Battuta, who visited China in 1347: | The characteristics of the Chinese ships of the period are described by Western travelers to the East, such as [[Ibn Battuta]] and [[Marco Polo]]. According to Ibn Battuta, who visited China in 1347: | ||

| − | <blockquote><p>…We stopped in the port of [[Calicut]], in which there were at the time thirteen Chinese vessels, and disembarked. [[China Sea]] traveling is done in Chinese ships only, so we shall describe their arrangements. The Chinese vessels are of three kinds; large ships called chunks ([[junk (sailing)|junks]]), middle sized ones called zaws ([[dhow]]s) and the small ones [[kakams]]. | + | <blockquote><p>…We stopped in the port of [[Calicut]], in which there were at the time thirteen Chinese vessels, and disembarked. [[China Sea]] traveling is done in Chinese ships only, so we shall describe their arrangements. The Chinese vessels are of three kinds; large ships called chunks ([[junk (sailing)|junks]]), middle sized ones called zaws ([[dhow]]s) and the small ones [[kakams]]. The large ships have anything from twelve down to three sails, which are made of bamboo rods plaited into mats. They are never lowered, but turned according to the direction of the wind; at anchor they are left floating in the wind.</p> |

| − | <p>Three smaller ones, the "half," the "third" and the "quarter," accompany each large vessel. | + | <p>Three smaller ones, the "half," the "third" and the "quarter," accompany each large vessel. These vessels are built in the towns of [[Quanzhou|Zaytun]] and [[Sin-Kalan]]. The vessel has four decks and contains rooms, cabins, and saloons for merchants; a cabin has chambers and a lavatory, and can be locked by its occupants.</p> |

| − | <p>This is the manner after which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three [[ell]]s in length. | + | <p>This is the manner after which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three [[ell]]s in length. When these walls have thus been built the lower deck is fitted in and the ship is launched before the upper works are finished."'' (Ibn Battuta).</p></blockquote> |

==Zheng He and Islam in Southeast Asia== | ==Zheng He and Islam in Southeast Asia== | ||

{{Islam and China}} | {{Islam and China}} | ||

| − | [[Indonesia]]n religious leader and Islamic scholar [[Hamka]] (1908–1981) wrote in 1961: | + | [[Indonesia]]n religious leader and Islamic scholar [[Hamka]] (1908–1981) wrote in 1961: ''"The development of Islam in Indonesia and [[Malaya]] is intimately related to a Chinese Muslim, Admiral Zheng He."''<ref>Rosey Wang Ma,[http://210.0.141.99/eng/malaysia/ChineseMuslim_in_Malaysia.asp Chinese Muslims in Malaysia History and Development], Chinese Muslims in Malaysia. Retrieved October 19, 2007.</ref> In Malacca, Zheng He built granaries, warehouses and a stockade, and it is likely that he left behind many of his Muslim crews. Much of the information on Zheng He's voyages was compiled by [[Ma Huan]], also Muslim, who accompanied Zheng He on several of his inspection tours and served as his chronicler and interpreter. In his book ''The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores'' (Chinese: 瀛涯勝覽) written in 1416, Ma Huan gave very detailed accounts of his observations of the peoples' customs and lives in ports they visited. Zheng He had many Muslim eunuchs as his companions. At the time when his fleet first arrived in Malacca, there were already Chinese of the '[[Muslim]]' faith living there. Ma Huan talks about them as ''tangren'' (Chinese: 唐人) who were Muslim. According to Ma Huan, Zheng He’s entourage frequented mosques, actively propagated the Islamic faith, established Chinese Muslim communities and built mosques. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Indonesian scholar Slamet Muljana writes: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>"Zheng He built Chinese Muslim communities first in [[Palembang]], then in San Fa (West Kalimantan), subsequently he founded similar communities along the shores of [[Java]], the [[Malay Peninsula]] and the [[Philippines]]. They propagated the Islamic faith according to the [[Hanafi]] school of thought and in Chinese language." When the Chinese naval expeditions were suspended after Zheng He's death, the Hanafi Islam that Zheng He and his followers propagated lost almost all contact with Islam in China, and gradually was totally absorbed by the local Shafi’i sect.</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===In Malacca=== | ===In Malacca=== | ||

| − | + | When Melaka was successively colonized by the [[Portugal|Portuguese]], the [[Netherlands|Dutch]], and later the [[Great Britain|British]], Chinese were discouraged from converting to Islam. Many of the Chinese Muslim mosques became San Bao Chinese temples commemorating Zheng He. After a lapse of six hundred years, the influence of Chinese Muslims in Malacca had almost disappeared. <ref>Leo Suryadinata, (ed.) ''Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia.'' (Singapore Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005), note [http://www.infobold.com/ChinaBooks/search.cfm?UR=26121&search_stage=details&records_to_display=50&this_book_number=10]. Retrieved January 15, 2008. </ref> | |

| − | + | According to the [[Malaysia]]n history, Sultan [[Mansur Shah of Malacca|Mansur Shah]] (ruled 1459–1477) dispatched Tun Perpatih Putih as his envoy to China and carried a letter from the Sultan to the Ming Emperor. Tun Perpatih succeeded in impressing the Emperor of Ming with the fame and grandeur of Sultan Mansur Shah. In the year 1459, a princess [[Hang Li Po]] (or Hang Liu), was sent by the emperor of Ming to marry Malacca Sultan Mansur Shah (ruled 1459–1477). The princess came with her entourage of five hundred male servants and a few hundred handmaidens. They eventually settled in [[Bukit Cina]], [[Malacca]]. The descendants of these people, from mixed marriages with the local natives, are known today as [[Peranakan]]: Baba (the male title) and [[Nyonya]] (the female title). | |

| − | + | In Malaysia today, many people believe that it was Admiral Zheng He (died 1433) who sent princess [[Hang Li Po]] to Malacca in year 1459. However there is no record of Hang Li Po (or Hang Liu) in Ming documents, she is known only from Malacca folklore. The so-called Peranakan in Malacca were probably Tang-Ren or Hui Chinese Muslims who came with Parameswara, the founder of Malacca, from [[Palembang]], [[Java]] and other places as refugees of the declining [[Srivijaya]] kingdom. Some of the Chinese Muslims were soldiers and served as warriors and bodyguards to protect the Sultanate of Malacca. | |

| − | + | In 1411, Admiral Zheng He brought Parameswara, his wife and 540 officials to China to pay homage to Emperor [[Yongle]]. Upon their arrival, a grand welcoming party was held. Animals were sacrificed, Parameswara was granted a two-piece gold-embroidered suit of clothing with dragon motifs, Kylin robe, gold and silverware, silk lace bed quilt, and gifts for all officials and followers. Upon returning home, Parameswara was granted a jade belt, brace, saddle, and coroneted suit for his wife. Upon reaching the heaven’s gate (China), Parameswara was again granted a jade belt, brace, saddle, a hundred gold & platinum pieces, 400,000 banknotes, 2600 cash, 300 pieces of silk brocade voile, 1,000 pieces of silk, two pieces of whole gold plait, two pieces of knee-length gown with gold threads woven through sleeves…. On his return trip from China, Parameswara was so impressed by Zheng He that he adopted the name Sultan Iskandar Shah. Malacca prospered under his leadership and became a half-way port for trade between India and China. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | == Popular Theories == | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Former British submarine commander [[Gavin Menzies]] in his book ''1421: The Year China Discovered the World'' claims that several parts of Zheng's fleet explored virtually the entire globe, discovering West Africa, North and South America, Greenland, Iceland, Antarctica and Australia before the voyages of [[Ferdinand Magellan]] and [[Christopher Columbus]]. Menzies also claims that Zheng's wooden fleet passed through the Arctic Ocean. Menzies proposes that Zheng He’s voyages, records, and maps are the sources for some of the other [[Ancient world maps]], which he claims depicted the [[Americas]], [[Antarctica]], and the tip of [[Africa]] before the official European discovery of these areas, and the drawings of the [[Fra Mauro map]] or the [[De Virga world map]]. However none of the citations in''1421'' are from Chinese sources and scholars in China do not share Menzies' assertions. | |

| − | + | A related book, ''The Island of Seven Cities: Where the Chinese Settled When They Discovered America'' by Paul Chiasson maintains that a nation of native peoples known as the Mi'kmaq on the east coast of Canada are descendants of Chinese explorers, offering evidence in the form of archaeological remains, customs, costume, and artwork. Several advocates of these theories believe that Zheng He also discovered modern day New Zealand on either his sixth or seventh expedition. | |

| − | + | It has been suggested by some historians and mentioned in a recent [[''National Geographic'']] article on Zheng He that [[Sindbad the Sailor]] (also spelled "Sinbad," from Arabic السندباد—As-Sindibad) and the collection of travel-romances that make up the "Seven Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor" found in [[The Book of One Thousand and One Nights]] (Arabian Nights) were influenced heavily by the cumulative tales of many seafarers that had followed, traded and worked in various support ships as part of the armada of Chinese Ming Imperial Treasure Fleets. This belief is supported in part by the similarities in Sindbad's name and the various iterations of Zheng in Arabic and Mandarin (pinyin: Mǎ Sānbǎo; Cantonese: Máh Sāambóu; Arabic name: Mahmud Shams) along with the similarities in the number (seven) and general locations of voyages between Sindbad and Zheng. This idea has no credibility within the scholarly community. | |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references /> | ||

| − | == | + | == References == |

| − | |||

| − | + | * Dreyer, Edward L. 2006. ''Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming, 1405–1433.'' (Library of World Biography Series). London: Longman. ISBN 0321084438. | |

| + | * Filesi, Teobaldo. David Morison (trans.) ''China and Africa in the Middle Ages.'' (London: Frank Cass, 1972. | ||

| + | * Finlay, Robert. [http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jwh/15.2/finlay.html How (not) to rewrite World History. Gavin Menzies and the Chinese Discovery of America], ''Journal of World History'' 15 (2) (2004): S.229–242. Retrieved October 19, 2007. | ||

| + | * Kahn, Joseph. [http://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/20/international/asia/20letter.html China Has an Ancient Mariner to Tell You About]. July 20, 2005, the ''New York Times''. Retrieved October 19, 2007. | ||

| − | The | + | * Levathes, Louise. 1997. ''When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433.'' Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195112075. |

| + | * Ma, Huan. 1970. ''Ying-yai Sheng-lan, The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores (1433), translated from the Chinese text edited by Feng Ch'eng Chun with introduction, notes and appendices by J.V.G. Mills.'' White Lotus Press. Reprinted 1970, 1997. ISBN 9748496783. | ||

| + | * Menzies, Gavin 2003. ''1421: The Year the Chinese Discovered the World.'' Morrow/Avon. ISBN 0060537639. (Scholars consider this book, insofar as it relates to the Chinese discovery of America, to lack factual foundation: | ||

| + | * 黃振翔: [http://proj.ncku.edu.tw/chengho/newsletter/no17.html Newsletter on Cheng-Ho]. Retrieved October 19, 2007. | ||

| + | * Suryadinata, Leo (ed.) ''Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia.'' Singapore Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005. ISBN 9812303294. Collection of essays written from Chinese points of view. | ||

| + | * Viviano, Frank. 2005. "China's Great Armada," ''National Geographic'' 208(1)(July 2005):28–53. | ||

| + | * Wilford, John Noble. [http://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/02/books/review/02WILFORT.html?tntemail1 Pacific Overtures], a book review of ''1421'' by a science editor at the ''New York Times''. February 2, 2003. Retrieved October 19, 2007. | ||

| − | + | * Zhang Yen-Yu and Zhong Hua Shu Ju (Editor). ''History of the Ming Dynasty, Complete 28 Volume Set'' (Ming Shu) (Official Dynastic Histories of China) Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju, 1st edition, 1995. (in Chinese) ISBN 7101003273 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | There are other books, publications and papers available (especially in Chinese), but they have not yet been translated into English. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == External links == | |

| − | + | All links retrieved July 3, 2013. | |

| − | + | * [http://proj.ncku.edu.tw/chengho/ Newsletter on Cheng-Ho]. National Cheng Hang University. (in Chinese) | |

| − | + | * FSTC Ltd. [http://www.muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?ArticleID=218 Zheng He - The Chinese Muslim Admiral]. 2001, ''MuslimHeritage.com''. | |

| − | Geoff Wade | + | * [http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/swimming_dragons.shtml BBC radio program "Swimming Dragons"]. BBC Radio. |

| + | * Dr. Siu-Leung Lee [http://www.asiawind.com/zhenghe The Mystery of Zheng He and America (June 2006)]. ''www.asiawind.com''. | ||

| + | * ''Economist'' [http://www.economist.com/displayStory.cfm?story_id=5381851 China beat Columbus to it, perhaps]. "Chinese cartography: A map that revises history." | ||

| + | * [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4609074.stm BBC News China map lays claim to Americas]. January 13, 2006. | ||

| + | * [http://h-net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-Asia&month=0601&week=b&msg=gv1CuUMQ0QkDD0gKTUJ//A&user=&pw= Exchange between Liu Gang and Geoff Wade]. | ||

| + | * [http://www.laputanlogic.com/articles/2006/01/16-0036-4322.html Laputan Logic: China's Own Vinland Map] Liu Gang's map, Chinese cartography and the Island of California myth. | ||

| + | * [http://www7.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0507/feature2/index.html National Geographic magazine special feature "China's Great Armada" (July 2005)]. | ||

| + | * [http://www.chinapage.com/chengho.html The Great Chinese Mariner Zheng He (brief biography with map and images)]. | ||

| + | * [http://www.1421exposed.com/ Academic website debunking Menzies' theories and the map]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Category:explorers]] | |

| + | [[Category:history and biography]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credits|Zheng_He|147099017}} | {{credits|Zheng_He|147099017}} | ||

Revision as of 15:43, 3 July 2013

- For the Three Kingdoms general, see Zhang He.

Zheng He (Traditional Chinese: 鄭和; Simplified Chinese: 郑和; Hanyu Pinyin: Zhèng Hé; Wade-Giles: Cheng Ho; Birth name: 馬三寶 / 马三宝; pinyin: Mǎ Sānbǎo; Islamic name: حجّي محمود شمس Hajji Mahmud Shams) (1371–1433), was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat and fleet admiral, who made the voyages collectively referred to as the travels of "Eunuch Sanbao to the Western Ocean" (Chinese: 三保太監下西洋)[1] or "Zheng He to the Western Ocean," from 1405 to 1433.

As a young boy, Zheng He was taken captive by the Ming and made a eunuch in the imperial service. He became a close confidant of the Yongle Emperor. Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He commanded a series of seven naval expeditions sponsored by the Ming government to establish a Chinese presence and extend the tributary system to the maritime nations in Southeast Asia. Zheng He set sail on his first voyage on July 11, 1405, commanding 62 treasure ships, 190 smaller ships and 27,800 men. At each port, Zheng He demanded that the inhabitants submit to the “Son of Heaven” (tianzi, the Chinese Emperor), and rewarded those who cooperated with gifts. Zheng He brought back emissaries from 36 countries who agreed to a tributary relationship, along with rich and unusual gifts, including African zebras and giraffes that ended their days in the Ming imperial zoo. Zheng He died during the seventh voyage and was buried at sea off the Malabar coast near Calicut in Western India.

Life

Zheng He was born in 1371 of the Hui ethnic group in Kunyang (昆阳), Jinning (晋宁), modern-day Yunnan Province (雲南),[2][3] one of the last possessions of the Mongols of the Yuan Dynasty before being conquered by the Ming Dynasty. According to his biography in the History of Ming, he was originally named Ma Sanbao (Ma Ho; 馬三保). Zheng belonged to the Semu or Semur caste which practiced Islam. He was a sixth-generation descendant of Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, a famous Khwarezmian Yuan governor of Yunnan Province from Bukhara in modern day Uzbekistan. His family name "Ma" came from Shams al-Din's fifth son Masuh (Mansour). Both his father Mir Tekin and grandfather Charameddin had traveled on the hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, and their travels contributed much to the young boy's education.

In 1381, following the fall of the Yuan Dynasty, a Ming army was dispatched to Yunnan to put down the Mongol rebel Basalawarmi, commonly known as the Prince of Liang, a descendant of Kublai Khan and a Yuan Dynasty loyalist. Zheng He, then only a young boy of eleven years, was taken captive by that army and castrated, becoming a eunuch. He was made an orderly in the army, and by 1390, when the army was placed under the command of the Prince of Yen, Zheng He (Ma Ho) had distinguished himself as a junior officer, skilled in war and diplomacy. He became a close confidant of Prince of Yen. In 1400, the Prince of Yen revolted against his nephew, the Jianwen (Chien-wen) Emperor (建文帝; the second Emperor of the Ming dynasty, personal name Zhu Yunwen), and took the throne in 1402 as the Yongle Emperor]] (永楽帝) of China (reigned 1403–1424, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty). The Yongle emperor conferred the name Zheng He as a reward for his support in the Yongle rebellion against the Jianwen Emperor (建文帝 ). Zheng He studied at Nanjing Taixue (The Imperial Central College). The Ming court then sought to display its naval power to the maritime states of South and Southeast Asia. The Chinese had been expanding their influence across the seas for three hundred years, establishing an extensive sea trade to bring spices and raw materials to China. Chinese travelers visited foreign nations, and Indian and Muslim visitors had widened China’s geographical horizons. By the beginning of the Ming dynasty, shipbuilding and the art of navigation had reached new heights in China.

Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming government sponsored a series of seven naval expeditions. Emperor Yongle intended them to establish a Chinese presence, impose imperial control over trade, and impress foreign peoples in the Indian Ocean basin. He also might have wanted to extend the tributary system, by which Chinese dynasties traditionally recognized foreign peoples.

Zheng He was selected by the Yongle Emperor to be commander in chief of the missions to the “Western Oceans.” He set sail on his first voyage on July 11, 1405, commanding 62 treasure ships and 27,800 men. Many of these ships were mammoth nine-masted "treasure ships," by far the largest marine craft the world had ever seen. The fleet visited Annan, Champa (now South Vietnam), Siam, Malacca, and Java; then sailed through the Indian Ocean to Calicut, Cochin, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), returning to China in 1407.

On his second voyage, in 1409, Zheng He (Cheng Ho) encountered hostility from King Alagonakkara of Ceylon. He defeated his forces and took the King back to Nanking as a captive to apologize to the Emperor. In 1411, Zheng He (Cheng Ho) set out on his third voyage, sailing to Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. On his return he touched at Samudra, on the northern tip of Sumatra. Zheng He set out on his fourth voyage in 1413. After stopping at the principal ports of Asia, he proceeded westward from India to Hormuz. A part of the fleet then cruised southward down the Arabian coast, the Persian Gulf and Arabia, visiting Djofar and Aden. A Chinese mission visited Mecca and continued to Egypt. The fleet visited Brava and Malindi in what is now Kenya, and almost reached the Mozambique Channel. On his return to China in 1415, Cheng Ho brought envoys from more than 30 states of South and Southeast Asia to pay homage to the Chinese emperor. During Zheng He (Cheng Ho)'s fifth voyage (1417–1419), the Ming fleet revisited the Persian Gulf and the east coast of Africa. In 1421, a sixth voyage was launched to return the foreign emissaries to their homes, again visiting Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and Africa.

Final Voyage

In 1424, the Yongle Emperor died. His successor, the Hongxi Emperor (reigned 1424–1425), decided to curb Zheng He’s influence at court and appointed him garrison commander in Nanking. Zheng He made one final voyage under the Xuande Emperor (reigned 1426–1435), visiting the states of Southeast Asia, the coast of India, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the east coast of Africa, but after that the Chinese treasure ship fleets were disbanded. Zheng He died during the treasure fleet's last voyage. Although he has a tomb in China, it is empty: he was, like many great admirals, buried at sea.[4]

The records of Zheng He's last two voyages, which were believed to have been his farthest, were unfortunately destroyed by the Ming emperor. Therefore it can never be ascertained exactly where Zheng sailed on these two expeditions. The traditional view is that he went as far as Persia. It is now the widely accepted view that his expeditions went as far as the Mozambique Channel in East Africa, from the ancient Chinese artifacts discovered there.

International Relations

At each port, Zheng He demanded that the inhabitants submit to the “Son of Heaven” (tianzi, the Chinese Emperor), and rewarded those who cooperated with gifts. Throughout his travels, Zheng He liberally dispensed Chinese gifts of silk, porcelain, and other goods. In return, he received rich and unusual presents from his hosts, including African zebras and giraffes that ended their days in the Ming imperial zoo. Zheng He and his company paid respects to local deities and customs, and in Ceylon they erected a monument honoring Buddha, Allah, and Vishnu.

Ultimately, 36 countries in what the Chinese called the “Western Ocean” agreed to a tributary relationship with China. Zheng He generally sought to attain his goals through diplomacy, and his large army awed most would-be enemies into submission. But a contemporary reported that Zheng He "walked like a tiger," and did not shrink from violence when he considered it necessary to impress foreign peoples with China's military might. He ruthlessly suppressed pirates who had long plagued Chinese and southeast Asian waters. He also intervened in a civil disturbance in order to establish his authority in Ceylon, and he made displays of military force when local officials threatened his fleet in Arabia and east Africa. From his fourth voyage, he brought envoys from 30 states who traveled to China and paid their respects at the Ming court.

Legacy

Zheng He’s missions were impressive demonstrations of organizational capability and technological advancement, but did not lead to significant trade, since Zheng He was an admiral and an official, not a merchant. Chinese merchants continued to trade in Japan and southeast Asia, but Imperial officials gave up any plans to maintain a Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean, and even destroyed most of the nautical charts that Zheng He had carefully prepared. Their motivations were political; during much of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), the eunuchs exercised great power in the imperial court, at the expense of the Confucian civil bureaucracy. The expeditions of Zheng He, who was himself a eunuch, were strongly supported by eunuchs in the court and bitterly opposed by the Confucian scholar bureaucrats.[5]

During the 1950s, historians including John Fairbank and Joseph Needham popularized the idea that after Zheng's voyages, China turned away from the seas and underwent a period of technological stagnation. Most current historians of China question the accuracy of this view, pointing out that Chinese maritime commerce did not stop after Zheng He, and that active Chinese trading with India and East Africa continued long after the time of Zheng and Chinese ships continued to dominate Southeast Asian commerce until the nineteenth century. The travels of the Chinese Junk Keying to the United States and England between 1846 and 1848 testify to the power of Chinese shipping. Historians such as Jack Goldstone argue that the Zheng He voyages ended for practical reasons that did not reflect the technological level of China[6] Starting in the early fifteenth century, China experienced increasing pressure from resurgent Mongolian tribes from the north. In 1421 the emperor Yongle (the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty) moved his capital north from Nanjing to present-day Beijing, from where, at considerable expense, China launched annual military expeditions to weaken the Mongolians. These land campaigns and a massive expansion of the Great Wall of China took precedence over state-sponsored naval explorations.

Zheng He's tomb and museum

. Zheng He's tomb in Nanjing has been repaired and a small museum has been built next to it. The tomb is empty as he was buried at sea off the Malabar coast near Calicut in Western India. However, his sword and other personal possessions were interred in a typical Muslim tomb inscribed with Arabic characters.

Zheng He as a Chinese Muslim

Zheng He travelled to Mecca, though he did not perform the pilgrimage itself. The government of the People's Republic of China uses him as a model to integrate the Muslim minority into the Chinese nation.

Zheng He was a living example of religious tolerance, perhaps even syncretism, or at least a master of diplomacy. The Galle Trilingual Inscription set up by Zheng He around 1410 in Sri Lanka records the offerings he made at a Buddhist mountain. "Inscriptions written in Chinese, Tamil and Persian praise Buddha, Shiva and Allah in equal measure."[7]

Around 1431, he set up a commemorative pillar at the temple of the Daoist goddess Tian Fei, the Celestial Spouse, in Fujian( 福建) province, to whom he and his sailors prayed for safety at sea.[8] This pillar records his veneration for the goddess and his belief in her divine protection, as well as a few details about his voyages.[9]

We have traversed more than 100,000 li (50,000 kilometers) of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising in the sky, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds day and night, continued their course [as rapidly] as a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare…

—(Tablet erected by Zheng He, Changle, Fujian, 1432. Louise Levathes

Voyages

| Order | Time | Regions along the way[10] |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Voyage | 1405-1407 | Champa, Java, Palembang, Malacca, Aru, Sumatra, Lambri, Ceylon, Kollam, Cochin, Calicut |

| 2nd Voyage | 1407-1408 | Champa, Java, Siam, Sumatra, Lambri, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon |

| 3rd Voyage | 1409-1411 | Champa, Java, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Quilon, Cochin, Calicut, Siam, Lambri, Kaya, Coimbatore, Puttanpur |

| 4th Voyage | 1413-1415 | Champa, Java, Palembang, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Cochin, Calicut, Kayal, Pahang, Kelantan, Aru, Lambri, Hormuz, Maldives, Mogadishu, Brawa, Malindi, Aden, Muscat, Dhufar |

| 5th Voyage | 1416-1419 | Champa, Pahang, Java, Malacca, Sumatra, Lambri, Ceylon, Sharwayn, Cochin, Calicut, Hormuz, Maldives, Mogadishu, Brawa, Malindi, Aden |

| 6th Voyage | 1421-1422 | Hormuz, East Africa, countries of the Arabian Peninsula |

| 7th Voyage | 1430-1433 | Champa, Java, Palembang, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Calicut, Hormuz... (17 politics in total) |

Size of Zheng He’s Ships

Ancient chronicles

Treasure ship is the name of a type of vessel that the Chinese admiral Zheng He sailed in. His fleet included 62 treasure ships, with some said to have reached 600 feet (146 meters) long. The fleet was manned by over 27,000 crew members, including navigators, explorers, sailors, doctors, workers, Muslim teachers, and soldiers.

According to ancient Chinese sources, Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. The 1405 expedition consisted of 27,800 men and a fleet of 62 treasure ships supported by approximately 190 smaller ships.[11][12] The fleet included:

The dimensions of the Zheng He's ships according to ancient Chinese chronicles and disputed by modern scholars (see below):

- "Treasure ships", used by the commander of the fleet and his deputies (nine-masted, said to be about 126.73 meters (416 ft) long and 51.84 meters (170 ft) wide), according to later writers. The great size of these ships was probably exaggerated by later writers. The treasure ships purportedly weighed as much as 1,500 tons.126.73m by 51.84 m (415.780ft by 170.078ft)[13] [14] By way of comparison, a modern ship of about 1,200 tons is 60 meters (200 ft) long [3], and the ships Christopher Columbus sailed to the New World in 1492 were about 70-100 tons and 17 meters (55 ft) long.[15]

- "Horse ships", carrying tribute goods and repair material for the fleet (eight-masted, about 103 m (339 ft) long and 42 m (138 ft) wide).[16]

- "Supply ships", containing staple for the crew (seven-masted, about 78 m (257 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) wide).[17]

- "Troop transports", six-masted, about 67 m (220 ft) long and 25 m (83 ft) wide).[18]

- "Fuchuan warships", five-masted, about 50 m (165 ft) long).[19]

- "Patrol boats", eight-oared, about 37 m (120 feet) long).[20]

- "Water tankers", with 1 month supply of fresh water. 126.73 m by 51.84 m (415.780ft by 170.078ft)[21]

Six more expeditions took place, from 1407 to 1433, with fleets of comparable size.[22]

Modern scholarship

The dimensions of the treasure ships, as recorded in later historical chronicles, are disputed by scholars. It is probable that the actual size of the ships was smaller, since in later historical periods wooden ships approaching this size (such as HMS Orlando) were unwieldy and visibly undulated with the waves, even with steel braces in the hull. The problem of "hogging," the tendency of the largest wooden ships to sag (like a pig's body) because of buoyancy in the middle, would have been impossible to solve. The length-to-width ratio of 2.47 is not well suited for fast navigation on the oceans. Hydrodynamic models have proved that ships with such dimension are unsailable in open seas.

Recent research suggests that the actual length of the biggest treasure ships may have lain between 59 m and 84 m.[23] If the treasure ships actually had the dimensions attributed to them, they would have been several times larger than any wooden ship ever recorded, including the largest l'Orient (65 m long). The length of the treasure ships would have been equivalent to that of the first generation aircraft carriers in the early twentieth century. Research on the original source of these dimensions indicates that they came from a novel written in the sixteenth century. [24]

Accounts of Medieval Travelers

The characteristics of the Chinese ships of the period are described by Western travelers to the East, such as Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo. According to Ibn Battuta, who visited China in 1347:

…We stopped in the port of Calicut, in which there were at the time thirteen Chinese vessels, and disembarked. China Sea traveling is done in Chinese ships only, so we shall describe their arrangements. The Chinese vessels are of three kinds; large ships called chunks (junks), middle sized ones called zaws (dhows) and the small ones kakams. The large ships have anything from twelve down to three sails, which are made of bamboo rods plaited into mats. They are never lowered, but turned according to the direction of the wind; at anchor they are left floating in the wind.

Three smaller ones, the "half," the "third" and the "quarter," accompany each large vessel. These vessels are built in the towns of Zaytun and Sin-Kalan. The vessel has four decks and contains rooms, cabins, and saloons for merchants; a cabin has chambers and a lavatory, and can be locked by its occupants.

This is the manner after which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three ells in length. When these walls have thus been built the lower deck is fitted in and the ship is launched before the upper works are finished." (Ibn Battuta).

Zheng He and Islam in Southeast Asia

Template:Islam and China Indonesian religious leader and Islamic scholar Hamka (1908–1981) wrote in 1961: "The development of Islam in Indonesia and Malaya is intimately related to a Chinese Muslim, Admiral Zheng He."[25] In Malacca, Zheng He built granaries, warehouses and a stockade, and it is likely that he left behind many of his Muslim crews. Much of the information on Zheng He's voyages was compiled by Ma Huan, also Muslim, who accompanied Zheng He on several of his inspection tours and served as his chronicler and interpreter. In his book The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores (Chinese: 瀛涯勝覽) written in 1416, Ma Huan gave very detailed accounts of his observations of the peoples' customs and lives in ports they visited. Zheng He had many Muslim eunuchs as his companions. At the time when his fleet first arrived in Malacca, there were already Chinese of the 'Muslim' faith living there. Ma Huan talks about them as tangren (Chinese: 唐人) who were Muslim. According to Ma Huan, Zheng He’s entourage frequented mosques, actively propagated the Islamic faith, established Chinese Muslim communities and built mosques.

Indonesian scholar Slamet Muljana writes:

"Zheng He built Chinese Muslim communities first in Palembang, then in San Fa (West Kalimantan), subsequently he founded similar communities along the shores of Java, the Malay Peninsula and the Philippines. They propagated the Islamic faith according to the Hanafi school of thought and in Chinese language." When the Chinese naval expeditions were suspended after Zheng He's death, the Hanafi Islam that Zheng He and his followers propagated lost almost all contact with Islam in China, and gradually was totally absorbed by the local Shafi’i sect.

In Malacca

When Melaka was successively colonized by the Portuguese, the Dutch, and later the British, Chinese were discouraged from converting to Islam. Many of the Chinese Muslim mosques became San Bao Chinese temples commemorating Zheng He. After a lapse of six hundred years, the influence of Chinese Muslims in Malacca had almost disappeared. [26]

According to the Malaysian history, Sultan Mansur Shah (ruled 1459–1477) dispatched Tun Perpatih Putih as his envoy to China and carried a letter from the Sultan to the Ming Emperor. Tun Perpatih succeeded in impressing the Emperor of Ming with the fame and grandeur of Sultan Mansur Shah. In the year 1459, a princess Hang Li Po (or Hang Liu), was sent by the emperor of Ming to marry Malacca Sultan Mansur Shah (ruled 1459–1477). The princess came with her entourage of five hundred male servants and a few hundred handmaidens. They eventually settled in Bukit Cina, Malacca. The descendants of these people, from mixed marriages with the local natives, are known today as Peranakan: Baba (the male title) and Nyonya (the female title).

In Malaysia today, many people believe that it was Admiral Zheng He (died 1433) who sent princess Hang Li Po to Malacca in year 1459. However there is no record of Hang Li Po (or Hang Liu) in Ming documents, she is known only from Malacca folklore. The so-called Peranakan in Malacca were probably Tang-Ren or Hui Chinese Muslims who came with Parameswara, the founder of Malacca, from Palembang, Java and other places as refugees of the declining Srivijaya kingdom. Some of the Chinese Muslims were soldiers and served as warriors and bodyguards to protect the Sultanate of Malacca.

In 1411, Admiral Zheng He brought Parameswara, his wife and 540 officials to China to pay homage to Emperor Yongle. Upon their arrival, a grand welcoming party was held. Animals were sacrificed, Parameswara was granted a two-piece gold-embroidered suit of clothing with dragon motifs, Kylin robe, gold and silverware, silk lace bed quilt, and gifts for all officials and followers. Upon returning home, Parameswara was granted a jade belt, brace, saddle, and coroneted suit for his wife. Upon reaching the heaven’s gate (China), Parameswara was again granted a jade belt, brace, saddle, a hundred gold & platinum pieces, 400,000 banknotes, 2600 cash, 300 pieces of silk brocade voile, 1,000 pieces of silk, two pieces of whole gold plait, two pieces of knee-length gown with gold threads woven through sleeves…. On his return trip from China, Parameswara was so impressed by Zheng He that he adopted the name Sultan Iskandar Shah. Malacca prospered under his leadership and became a half-way port for trade between India and China.

Popular Theories

Former British submarine commander Gavin Menzies in his book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World claims that several parts of Zheng's fleet explored virtually the entire globe, discovering West Africa, North and South America, Greenland, Iceland, Antarctica and Australia before the voyages of Ferdinand Magellan and Christopher Columbus. Menzies also claims that Zheng's wooden fleet passed through the Arctic Ocean. Menzies proposes that Zheng He’s voyages, records, and maps are the sources for some of the other Ancient world maps, which he claims depicted the Americas, Antarctica, and the tip of Africa before the official European discovery of these areas, and the drawings of the Fra Mauro map or the De Virga world map. However none of the citations in1421 are from Chinese sources and scholars in China do not share Menzies' assertions.

A related book, The Island of Seven Cities: Where the Chinese Settled When They Discovered America by Paul Chiasson maintains that a nation of native peoples known as the Mi'kmaq on the east coast of Canada are descendants of Chinese explorers, offering evidence in the form of archaeological remains, customs, costume, and artwork. Several advocates of these theories believe that Zheng He also discovered modern day New Zealand on either his sixth or seventh expedition.

It has been suggested by some historians and mentioned in a recent ''National Geographic'' article on Zheng He that Sindbad the Sailor (also spelled "Sinbad," from Arabic السندباد—As-Sindibad) and the collection of travel-romances that make up the "Seven Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor" found in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights) were influenced heavily by the cumulative tales of many seafarers that had followed, traded and worked in various support ships as part of the armada of Chinese Ming Imperial Treasure Fleets. This belief is supported in part by the similarities in Sindbad's name and the various iterations of Zheng in Arabic and Mandarin (pinyin: Mǎ Sānbǎo; Cantonese: Máh Sāambóu; Arabic name: Mahmud Shams) along with the similarities in the number (seven) and general locations of voyages between Sindbad and Zheng. This idea has no credibility within the scholarly community.

Notes

- ↑ 三保太監下西洋. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ The Hui ethnic minority - People's Daily, People's Daily Online. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ [1] Zheng He Exhibitions at Singapore National Library. National Library Board, Singapore. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ The Seventh and Final Grand Voyage of the Treasure Fleet, The Mariners' Museum. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Richard Gunde, Zheng He's Voyages of Discovery, Berkeley: The Regents of the University of California. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Jack A. Goldstone, The Rise of the West—or Not?. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Alex Perry A Testament to an Odyssey, A Monument to a Failure Set in stone: Sri Lanka. TIME Asia, August 2001, 158 (781). Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ↑ Ancient Chinese Explorers, NOVA Online. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Zheng He's Inscription, the Regents of the University of Minnesota. excerpt from the book, Teobaldo Filesi, David Morison (trans.) China and Africa in the Middle Ages. (London: Frank Cass, 1972), 57-61. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Maritime Silk Road 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 7508509323

- ↑ Edward L. Dreyer. Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming, 1405–1433.(London: Longman, 2006), 122–124

- ↑ Briton charts Zheng He's course across globe, Ministry of Culture, P.R. China. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Zhang. "History of the Ming dynasty" («明史»), Zhang Tingyu chief editor, (originally published 1737), (“四十四丈一十八丈”)

- ↑ "Eunuch Sanbao's Journey to the Western Seas" («三宝太监西洋通俗演义记»),Luo Maodeng, (originally published 1597), (“宝船长四十四丈四,阔一十八丈,每只船上有九道桅。”)

- ↑ Keith A. Pickering.Columbus's Ships. www.columbusnavigation.com. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Zhang, 1737

- ↑ Zhang, 1737

- ↑ Zhang, 1737

- ↑ Zhang, 1737

- ↑ Zhang, 1737

- ↑ Zhang, 1737

- ↑ Dreyer, 2006

- ↑ Sally K. Church, "The Colossal Ships of Zheng He: Image or Reality?" (155-176);and "Zheng He; Images & Perceptions," in South China and Maritime Asia Volume 15, Hrsg: Roderich Ptak, Thomas O. Höllmann, (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag, 2005)

- ↑ For debates of these dimensions, see Chinese articles in National Cheng Kung University at National Cheng Kung University of Taiwan. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Rosey Wang Ma,Chinese Muslims in Malaysia History and Development, Chinese Muslims in Malaysia. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Leo Suryadinata, (ed.) Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia. (Singapore Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005), note [2]. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dreyer, Edward L. 2006. Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming, 1405–1433. (Library of World Biography Series). London: Longman. ISBN 0321084438.

- Filesi, Teobaldo. David Morison (trans.) China and Africa in the Middle Ages. (London: Frank Cass, 1972.

- Finlay, Robert. How (not) to rewrite World History. Gavin Menzies and the Chinese Discovery of America, Journal of World History 15 (2) (2004): S.229–242. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- Kahn, Joseph. China Has an Ancient Mariner to Tell You About. July 20, 2005, the New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- Levathes, Louise. 1997. When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195112075.

- Ma, Huan. 1970. Ying-yai Sheng-lan, The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores (1433), translated from the Chinese text edited by Feng Ch'eng Chun with introduction, notes and appendices by J.V.G. Mills. White Lotus Press. Reprinted 1970, 1997. ISBN 9748496783.

- Menzies, Gavin 2003. 1421: The Year the Chinese Discovered the World. Morrow/Avon. ISBN 0060537639. (Scholars consider this book, insofar as it relates to the Chinese discovery of America, to lack factual foundation:

- 黃振翔: Newsletter on Cheng-Ho. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- Suryadinata, Leo (ed.) Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia. Singapore Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005. ISBN 9812303294. Collection of essays written from Chinese points of view.

- Viviano, Frank. 2005. "China's Great Armada," National Geographic 208(1)(July 2005):28–53.

- Wilford, John Noble. Pacific Overtures, a book review of 1421 by a science editor at the New York Times. February 2, 2003. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- Zhang Yen-Yu and Zhong Hua Shu Ju (Editor). History of the Ming Dynasty, Complete 28 Volume Set (Ming Shu) (Official Dynastic Histories of China) Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju, 1st edition, 1995. (in Chinese) ISBN 7101003273

There are other books, publications and papers available (especially in Chinese), but they have not yet been translated into English.

External links

All links retrieved July 3, 2013.

- Newsletter on Cheng-Ho. National Cheng Hang University. (in Chinese)

- FSTC Ltd. Zheng He - The Chinese Muslim Admiral. 2001, MuslimHeritage.com.

- BBC radio program "Swimming Dragons". BBC Radio.

- Dr. Siu-Leung Lee The Mystery of Zheng He and America (June 2006). www.asiawind.com.

- Economist China beat Columbus to it, perhaps. "Chinese cartography: A map that revises history."

- BBC News China map lays claim to Americas. January 13, 2006.

- Exchange between Liu Gang and Geoff Wade.

- Laputan Logic: China's Own Vinland Map Liu Gang's map, Chinese cartography and the Island of California myth.

- National Geographic magazine special feature "China's Great Armada" (July 2005).

- The Great Chinese Mariner Zheng He (brief biography with map and images).

- Academic website debunking Menzies' theories and the map.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.