William Stukeley

The Rev. Dr William Stukeley FRS, FRCP, FSA (November 7, 1687 – March 3, 1765) was an English antiquary, one of the founders of field archaeology. He is best known for his pioneering investigations of Stonehenge and Avebury.

Trained in the medical profession and turning later in life to the ministry, Stukeley's work evidenced this combination of scientific and religious inquiry. His publications presented accurate, detailed observations of monuments and other structures that he found of interest together with elaborate accounts of their supposed religious, specifically Druidic, significance to their builders.

Stukeley's legacy includes both the scientific and the religious aspects. Archaeology developed as a scientific discipline and his drawings and descriptions continue to provide valuable data on structures he investigated, many of which have since been destroyed. Also, his interpretation of the great stone circles continues to inspire visitors seeking to connect to the spirituality and wisdom of the Druids.

Life

William Stukeley was born the son of a lawyer at Holbeach in Lincolnshire on the site of Stukeley Hall, a primary school that now bears his name. After taking his M.B. degree at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Stukeley went to London and studied medicine at St Thomas' Hospital. In 1710, he started in practice in Boston, Lincolnshire, returning in 1717 to London. In the same year, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society and, in 1718, joined in the establishment of the Society of Antiquaries, acting for nine years as its secretary. In 1719 Stukeley took his M.D. degree, and in 1720 became a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, publishing in the same year his first contribution to antiquarian literature.

Stukeley was one of the first learned gentlemen to be attracted to speculative freemasonry, newly fashionable after the appointment of the first noble Grand Master. His Diary and Commonplace Book of June 6, 1721, says "I was made a Freemason at the Salutation Tav., Tavistock Street, with Mr. Collins, Capt. Rowe, who made the famous diving Engine."[1] The same entry says he was the first person for many years who had been so made in London; there was great difficulty in finding sufficient members to perform the Ceremony; and immediately thereafter "Freemasonry took a run and ran itself out of breath through the folly of its members." His diary and papers are among the earliest sources on the subject of the new Grand Lodge.

In 1729 he was ordained in the Church of England and served as vicar in the parish of All Saints, Stamford, Lincolnshire, where he did a considerable amount of further research, not least on the town's lost Eleanor Cross. He was subsequently appointed rector of a parish in Bloomsbury, London.

Stukeley was a friend of Isaac Newton and wrote a memoir of his life (1752).

William Stukeley died in London on March 3, 1765.

Work

Stukeley began his archaological observations in 1710, and for a period of 15 years he made summer expeditions on horseback around the British countryside. Trained in the medical profession, he had an eye for detailed observation and he accurately described and sketched all that he found of interest on these trips. Always concerned to preserve as much as possible before monuments and other historical structures were destroyed by the ravages of time and the advances of civilization, particularly the agricultural and industrial revolutions, he published the results of his travels in Itinerarium Curiosum (1924) with the appropriate subtitle "An Account of the Antiquities, and Remarkable Curiosities in Nature or Art, Observed in Travels through Great Britain."

He was not only a keen observer and accurate portrayer of details in his sketches, Stukeley also had a gift for writing that gave the reader an exciting vision of the structures. Reflecting on Hadrian's Wall, he wrote:

This mighty wall of four score miles in length is only exceeded by the Chinese wall, which makes a considerable figure upon the terrestrial globe, and may be discerned at the moon.[3]

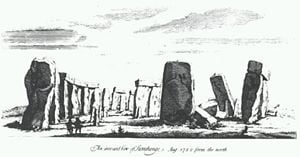

Stukeley's principal works, elaborate accounts of Stonehenge and Avebury, appeared in 1740 and 1743. These were supposed to be the first of a multi-volume universal history. Excited by John Aubrey's discoveries at Avebury in 1649, and his proposal that they were connected to Druids, Stukeley elaborated the idea that Stonehenge and Avebury were the religious products of an early Celtic Druid culture:

Our predecessors, the Druids of Britain, tho' left in the extremest west to the improvement of their own thoughts, yet advanc'd their inquiries, under all disadvantages, to such heights, as should make our moderns asham'd, to wink in the sunshine of learning and religion.[4]

His writings were so persuasive that the connection between these monuments and the Druids has been irrevocably forged in the minds of the public. He wrote copiously on other supposed Druid remains, becoming familiarly known as the "Arch-Druid." He also connected the serpentine shapes of the avenues connecting stone circles with the legends of dragons found throughout Britain.

Stukeley's ideas, while in some cases fanciful, were nonetheless based on serious inquiry and a substantial scientific background. He was also the first to recognize that alignment of Stonehenge on the solstices. Stukeley's work on Stonehenge was one of the first to attempt to date the monument.[5] He proposed that the builders of Stonehenge knew about magnetism, and had aligned the monument with magnetic north. Stukeley used some incomplete data about the variation of the North Magnetic Pole; he extrapolated that it oscillated in a regular pattern. Today it is known that the North Magnetic Pole wanders in an irregular fashion. However, Stukeley inferred that Stonehenge was completed in 460 B.C.E., which as we now know is several thousand years too late.

Legacy

Despite his extravagant theorizing, William Stukeley was an excellent archaeologist. His surveys remain of interest and value to this day.

Stukeley's illustrations and records have been instrumental in helping us realize what magnificent and extensive undertakings the Avebury and Stonehenge monuments were. During his visits to Avebury he witnessed much of the unforgivable destruction that took place. Without his meticulous notes and sketches researchers would have great difficulty in interpreting what remains there today. Discoveries such as those in the Beckhampton Avenue occurred as a result of Stukeley's earlier observations.

Although his passion for the Druids, and his romantic characterizations of their lives, in some part confused our understanding of these monumental stone circles, his vision and enthusiasm brought about an interest in the ancient cultures and people who built such incredible structures. The purpose of stone circles must indeed have been connected with prehistoric peoples' beliefs, and their construction can be used to infer much about their knowledge of about mathematics, engineering, and astronomy, as well as their social organization and religion. Stukeley pioneered such efforts, opening the way to our much greater understanding and appreciation for these people of times past.

Notes

- ↑ William Stukeley, The Commentarys, Diary, & Common-Place Book of William Stukeley & Selected Letters (London: Doppler Press, 1980).

- ↑ William Stukeley, Stonehenge, A Temple Restor'd to the British Druids (London: W. Innnys and R. Maney, 1740). Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ↑ Private letter published in The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley 3 (1887), 142.

- ↑ William Stukeley, Stonehenge: A Temple Restor'd to the British Druids, Preface (1740). Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ↑ Gerald S. Hawkins, Stonehenge Decoded (Hippocrene Books, 1988, ISBN 978-0880291477).

Publications

- Stukeley, William. Itinerarium Curiosum: Or, An Account of the Antiquities, and Remarkable Curiosities in Nature or Art, Observed in Travels through Great Britain, 2nd ed. Republished Gregg, 1969 (original 1724). ISBN 978-0576193122

- Stukeley, William. Stonehenge, a Temple Restor'd to the British Druids Forgotten Books, 2007 (original 1740). Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- Stukeley, William. Abury, a Temple of the British Druids. 1743.

- Stukeley, William. The Philosophy of Earthquakes, Natural and Religious, Or, An Inquiry Into their Cause and their Purpose London: C. Corbet, 1750. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- Stukeley, William. Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton's Life...1752: Being Some Account of his Family and Chiefly of the Junior Part of his Life. Taylor and Francis, 1936 (original 1752).

- Stukeley, William and Roger Gale. The Family Memoirs Of The Rev. William Stukeley And The Antiquarian And Other Correspondence. Kessinger Publishing, 2007 (original 1754). ISBN 978-0548190098

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burl, Aubrey. Rings of Stone: The Prehistoric Stone Circles of Britain and Ireland. The Harvill Press, 1999. ISBN 978-1860466618

- Burl, Aubrey and Neil Mortimer (eds.). Stukeley's Stonehenge: An Unpublished Manuscript 1721-1724. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0300098952

- Gjertsen, Derek. The Newton Handbook. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986. ISBN 0710202792

- Hawkins, Gerald S. Stonehenge Decoded. Hippocrene Books, 1988. ISBN 978-0880291477

- Haycock, David Boyd. William Stukeley: Science, Religion and Archaeology in Eighteenth-century England. Boydell Press, 2002. ISBN 0851158641

- Mortimer, Neil. Stukeley Illustrated: William Stukeley's Rediscovery of Britain's Ancient Sites. Green Magic, 2003. ISBN 0954296338

- Piggot, Stuart. William Stukeley: An Eighteenth-Century Antiquary. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1985. ISBN 0500013608

External links

All Links Retrieved May 21, 2008:

- Bronze Medal of William Stukeley at the British Museum

- John Aubrey & William Stukeley

- Text and engravings of Stukeley's Avebury survey online

- William Stukeley (1687 - 1765)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.