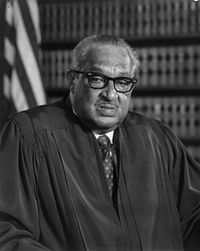

Thurgood Marshall

| Term of office | June 13, 1967 – June 28, 1991 |

| Preceded by | Tom C. Clark |

| Succeeded by | Clarence Thomas |

| Nominated by | Lyndon Baines Johnson |

| Date of birth | July 2, 1908 |

| Place of birth | Baltimore, Maryland |

| Date of death | January 24, 1993 |

| Place of death | Washington, D.C. |

| Spouse | {{{spouse}}} |

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American jurist and the first African-American to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States. Marshall was a man dedicated to assuring the basic freedoms expressed in the Constitution for all people. He lived during the time of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X and fought equally with them, though less attention is given to Marshall as a radical civil rights leader. He did not follow the religious and political activism of King nor in the fiery ideas of Malcolm X. Instead, he believed it was only through changing the laws of America that true equality could and would be reached. Many believe that the beginning of the civil rights era was marked by a case Marshall argued in the Supreme Court. By winning the infamous case, Brown vs. Board of Education, Marshall changed the law, and a new law was invoked. This decision outlawed segregation in public education. The outcome of the Brown case changed the very core of American society.

Although Marshall's work and ideas took many years to come to any sort of fruition, his tenure as the first black Justice to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States marked the beginning of 24 years of honest work and dedication for the rights of American citizens. He worked not only to secure equal rights and privileges for blacks, but also women, children, the homeless, and prisoners. When Marshall died in 1993, an editorial in the Washington Afro-American said "We make movies about Malcolm X, we get a holiday to honor Dr. Martin Luther King, but every day we live the legacy of Justice Thurgood Marshall."

Background

Thoroughgood Marshall was born to William Canfield and Norma Arica Marshall in Baltimore, Maryland, on July 2, 1908. He was named after his great-grandfather, a former slave and also a soldier who fought with the Union Army during the American Civil War. Thoroughgood changed his name to Thurgood in the second grade, claiming that his name had too many letters for anyone—let alone his teachers—to remember. His father, William, worked as a railroad porter and steward at an all-white club during Marshall's childhood. His mother was employed as an elementary school teacher in a segregated school. She was one of the first black women to graduate from Columbia's prestigious Teacher's College in New York City. His parents were tough, but kind. Often they made him prove every point or argument through debate and conversation. He credited this characteristic of his upbringing for helping him prove his cases in the courthouses. His family was known throughout the neighborhood as advocates of equality and fought for desegregation, long before he would help the law get passed in a courthouse. William Marshall was the first black man to serve in a grand jury in Baltimore.

Marshall attended Frederick Douglass High School in Baltimore. During school, he was rambunctious and occasionally disruptive. The common disciplinary form taken at his school was for the student to go to the basement to copy and memorize various sections of the Constitution. By the age of 16, he admitted to having the entire Constitution memorized. It was this first exposure to the Constitution that gave him the desire to become a lawyer. His parents also encouraged him to learn and to reason. The support of his parents and their belief that he could be anything he set his mind to—combined with the social stigma that he could never accomplish much considering his race and background—led Marshall on a fight to change the world.

Education

After high school, Marshall went on to study at Lincoln University in Chester, Pennsylvania, where his brother, William Aubrey Marshall, was also attending. During his education at Lincoln he found himself in the company of the future president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah; the famous musician, Cab Calloway; and the poet, Langston Hughes. Referencing Hughes in an interview, Marshall said that, "He knew everything there was to be known." He admired the poet greatly.

In 1929, he met his first wife, Vivian "Buster" Burey and they were married on September 4, 1929. Their 25-year marriage ended in 1955, when Buster died of breast cancer. In 1930, after graduating as valedictorian from Lincoln, Marshall applied to his hometown law school, the University of Maryland School of Law. The law school, like most other schools at the time, had a strict segregation policy, and Marshall was not admitted. Marshall never forgot this slight and later sued the law school for their policy in his case Murray vs. Pearson.

His mother sold her engagement and wedding rings to pay for the expenses of Marshall's housing and education at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he was accepted into the law school. It was at Howard that he met Charles Hamilton Houston, the dean. Before Houston took over the academic procedures at Howard, the school was known as the school for the less intelligent, a school where people who couldn't get in anywhere else came to be educated. Within three years Houston raised the bar at Howard University, making the standards of education higher, to the point where it became an accredited university. Houston is known for his famous saying, "Each one of you look to the man on your right and then look to the man on your left, and realize that two of you won't be here next year." Marshall took this advice to heart and found the dedication to succeed.

Marshall became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate black Greek-letter fraternity, established by African-American students in 1906. Again Houston challenged him. He loved to say that failing an average student gave him no pleasure at all, but he derived pleasure from failing and kicking out the smartest and most brilliant students at the school. During his first year, Marshall was the top student. His studies centered on the Constitution and digging out the facts of the laws. Houston often told the all-black population at Howard that they couldn't be as good as a white lawyer—they had to be better—much better—because they would never be treated as equals, so they had to make up the difference.

During his second and third years, Marshall became a student librarian, which provided for much of his tuition. He and Buster could not afford to live in Washington, so they made the long commute to Baltimore. Paramount in the education Marshall received at Howard was Houston's adamant teachings that the Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson, which brought the "separate but equal" ideology into existence, must be overturned.

Law career

Marshall graduated from Howard in 1933. Upon graduation, the dean of Harvard University offered Marshall a one-year scholarship to receive his SJD degree in constitutional law. The scholarship offered to him would have paid for his tuition, housing for his small family and even a little extra to spare, but he turned it down. The fire of his newly earned right to pursue his career in law led him to open up a small office in Baltimore. Cases were scarce, and in the first year Marshall ended up losing over $3,500 because he couldn't get enough cases. The office was small and filled with second-hand furniture. His mother came to see it and insisted that it needed a rug. The Marshalls had no money to spare, so his mother went to her home, took the rug off of her living room floor, and brought it to his office.

Murray v. Pearson

After that trying first year, Marshall was hired to work with the Baltimore division of the NAACP. He was assigned to represent Donald Gaines Murray in his first major civil rights case, Murray v. Pearson, 169 Md. 478 (1936). For Marshall, the case was personal as well as public. Murray was a young black graduate of Amherst College; he was an excellent student who had excelled in school, much like Marshall. He applied to the University of Maryland Law School and was denied. Charles Hamilton Houston served as Marshall's co-counsel, and he felt that this case was perfect to begin the battle of overturning the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. The "separate but equal" policy held by the university required black students to accept one of three options: 1) attend Morgan State University, 2) attend the Princess Anne Academy, or 3) attend out-of-state black institutions.

In 1935 Marshall argued the case for Murray. In court he voiced his strong belief when he said, "What's at stake here is more than the rights of my client. It's the moral commitment stated in our country's creed." He also proved that the policy was full of faults. There was no in-state college or university that had a law school to apply to, and these institutions were far below the standards held by the University of Maryland.

Even after a strong and eloquent fight, both Marshall and Houston expected to lose the case, but both began making plans for appeal to the federal courts. However, the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled against the state of Maryland and its attorney general, who represented the University of Maryland, stating "Compliance with the Constitution cannot be deferred at the will of the state. Whatever system is adopted for legal education now must furnish equality of treatment now." This was a moral victory for Marshall and Houston, as well as Murray, who was admitted to the university. This case did not have any authority outside of the state of Maryland, and it in no way overruled the Plessy case, but it was a milestone that would lead to the eventual desegregation of all schools throughout America.

Chief Counsel for the NAACP

In 1938, Marshall became a counsel for the NAACP. During his appointment of 23 years, he won 29 of the 32 cases he was given, making quite a reputation for himself. In 1940 Marshall won Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227. This marked the beginning of his career as a Supreme Court attorney; he was only 32 years old. Because of the remarkable success achieved by Marshall, the NAACP appointed him as chief counsel. He argued many other cases before the Supreme Court, including Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) in which the court declared that Texas must allow black voters to be able to register for primary elections; Shelley vs. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); Sweatt vs. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950), which put an end to "separate but equal" facilities in universities and professional offices across the country; and McLaurin vs. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950).

During his time at the NAACP, Marshall's office was located adjacent to W. E. B. Du Bois. Marshall reflected that Du Bois was often distant, remaining in his office for long hours and that his office was lined with books. Du Bois himself admitted to Marshall that one of his bad traits was his lack of socialization.

Marshall’s life was in endangered several times when he was sent into the Deep South to represent black clients who were victims of extreme racism. Once, he was followed after a hearing by white men who tried to lynch him and only through luck and a disguise was he able to escape. Another time, when he had to change trains on his way to Louisiana, he was approached by a white man who had a huge pistol attached to his hip. The white man looked at Thurgood and said, "Nigger boy, what are you doing here?" Thurgood responded that he was waiting for the train to Shreveport, Louisiana. The white man said, "There's only one more train comes through here and that's four o'clock and you'd better be on it because the sun is never going down on a live nigger in this town." Marshall remembered this experience and was often disturbed by the fact that that man could have simply shot him dead and he wouldn't have even had to go to court. It was experiences like these that kept him continually fighting to end racial discrimination.

During the 1950s, Marshall worked with J. Edgar Hoover, the director the Federal Bureau of Investigation. At their first meeting there was a lot of tension and fighting. They were both powerful men who knew what they wanted and they fought for it, but this dedication to a cause and ability to stand up for themselves led to a mutual respect, and finally a friendship. During their friendship, they both worked hard to fight against the communism that was seeping into American politics at the time. Marshall said in an interview later in his life that it was he who purged the NAACP of communist influences.

Marshall also earned the respect of President John F. Kennedy, who appointed Marshall to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961. Not all agreed with this appointment and there was a group of Democratic senators led by Mississippi's James Eastland and West Virginia's Robert Byrd who disagreed with Kennedy's choice, and they held up Marshall's confirmation. Thus, Thurgood had to serve the first few months under a “recess appointment.”[1] Marshall remained on that court for four years, maintaining a good relationship with President Kennedy. During this time he wrote over 150 decisions, many of them dealing with the rights of immigrants, double jeopardy, improper search and seizure, and privacy issues.

Later in his life, he received a phone call from a member of Hoover's private investigation of Martin Luther King, Jr. He told Marshall to tell King that Hoover had everything bugged everywhere King went. He said that King couldn't say or do anything without it all being recorded. Marshall related this information to King, but King had already suspected that something like this was going on. Marshall believed this to be wrong and wanted to make laws to amend such practices.

Brown v. Board of Education

As a lawyer, Marshall's most famous case was Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). This case all began with a little girl, Linda Brown, who had to walk over a mile through a railway switchyard to her all- black school when a white school was only seven blocks away. Oliver Brown, Linda's father, had tried to enroll her in the white school, but the principal refused. There had been many other similar situations, but the Brown family and the black people of the community rallied together and fought the separation law. Many thought it was "the right case at the right time" and the NAACP appointed Marshall to lead the case.

The arguments on both sides were extensive, with Marshall advocating the incontestable fact that segregation in school only prepared black children for the segregation of their lives in the future and left them with severe feelings of inferiority that needed to be stopped. Marshall's main goal was to finally put an end to the "separate but equal" policy which had dominated American life since the end of slavery. The court ruled in favor of Brown, and Brown went to the white school. However, ending the influences of racism did not come easily or quickly. But, since the Brown decision in May 1954, the rise of black graduates—not only from high school, but from college and other forms of higher education—has increased dramatically. Schools across America were desegregated, and the civil rights movement began in earnest.

U.S. Supreme Court

In 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him United States solicitor general, and on June 13, 1967, President Johnson appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court following the retirement of justice Tom C. Clark, saying that this was "the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place." Johnson later claimed that it was his appointment of Marshall that made him so unpopular with the American public. He thought that was one of his greatest mistakes, and he felt that if he hadn't appointed Marshall then he would have served another term as president.

Marshall believed it was the Vietnam War that made President Johnson unpopular with America. In fact, every president Marshall served under on the Supreme Court, including Johnson, requested that Marshall resign his position. Marshall said his response to each of them was two words, and one of them was an expletive.

Marshall was the first African-American appointed to the Supreme Court. This gained him approval from some African-Americans, but from others, like Malcolm X, he was publicly referred to as "half-white." Malcolm X said that Marshall was the white man's puppet, doing whatever they told him to do. They met once and Malcolm presented Marshall with a gun. Marshall claimed that his wife would not allow any weapon into their house and declined the gift. Marshall believed that was the root cause of the troubled relationship between the two of them.

Despite the presidents wanting Marshall to resign, he ended up serving on the Court for 24 years. He was a liberal, and remained a liberal. He compiled a court record that worked to promote what he had always tried to support, including Constitutional protection of individual rights, especially the rights of criminal suspects against the government. Marshall found an ally in Justice William Brennan, they often shared the same views and beliefs on the cases that were presented to them. Together they supported abortion rights and opposed the death penalty. Brennan and Marshall concluded in Furman v. Georgia that the death penalty was wrong, inhuman, and unconstitutional. They were both upset with the ruling of Gregg v. Georgia just three years after the Furman case, which stated that the death penalty was constitutional. After the Gregg case, Brennan or Marshall took turns advocating against the death penalty. Marshall also supported affirmative action, but believed that it could never truly work because a white man was always going to be more qualified than a black man because they were born white and automatically had more privileges. At the end of his tenure, he often felt that he was a dying voice and that his views were in the minority.

During his time on the Supreme Court, Marshall worked with many men, Chief Judge Douglas Ginsburg of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, well-known law professors Cass Sunstein and Eben Moglen, and prominent critical legal studies advocate and constitutional law professor Mark Tushnet.

Marshall announced his retirement at the end of his term on June 28, 1991, citing his age and declining health as reasons. He told reporters, "I'm getting old and coming apart." He used his sense of humor to cover up the deep regret and sadness he felt at having to retire from a position he loved.

Legacy

Before his appointment to serve on the Supreme Court, he represented and won more cases before the United States Supreme Court than any other American. He always stood up for what he believed in, he worked hard to overcome racial and other types of discrimination the legal way, in the court systems of the United States. He represented those who were not represented and he gave a voice to those who did not have one.

Marshall died of heart failure at National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, on January 24, 1993. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He had benefited from a wonderful second marriage to Cecilia "Cissy" Marshall, after the passing of his first wife. Together, he and Cissy had two sons: Thurgood Marshall, Jr. and John W. Marshall. Marshall, Jr. is a former top aide to President Bill Clinton. His son, John W. Marshall, is a former director of the United States Marshals Service, and since 2002 has served as Virginia secretary of public safety under governors Mark Warner and Tim Kaine.

Paul Gewirtz, the Potter Stewart Professor of Constitutional Law at Yale Law School, said of Marshall:

He grew up in a ruthlessly discriminatory world—a world in which segregation of the races was pervasive and taken for granted, where lynching was common, where the black man's inherent inferiority was proclaimed widely and wantonly. Marshall had the capacity to imagine a radically different world, the imaginative capacity to believe that such a world was possible, the strength to sustain that image in the mind's eye and the heart's longing, and the courage and ability to make that imagined world real.

Timeline of Marshall's life

1930 - Marshall graduates with honors from Lincoln University (cum laude)

1933 - Receives law degree from Howard University (magna cum laude); begins private practice in Baltimore, Maryland

1934 - Begins to work for Baltimore branch of the NAACP

1935 - Worked with Charles Houston, wins first major civil rights case, Murray v. Pearson

1936 - Becomes assistant special counsel for NAACP in New York

1940 - Wins Chambers v. Florida, the first of 29 Supreme Court victories

1944 - Successfully argues Smith v. Allwright, overthrowing the South's "white primary"

1948 - Wins Shelley v. Kraemer, in which Supreme Court strikes down legality of racially restrictive covenants

1950 - Wins Supreme Court victories in two graduate-school integration cases, Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents

1951 - Visits South Korea and Japan to investigate charges of racism in U.S. armed forces. He reported that the general practice was one of "rigid segregation."

1954 - Wins Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, landmark case that demolishes legal basis for segregation in America

1956 - Wins Gayle v. Browder, Ending the practice of segregation on buses and ending the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

1961 - Defends civil rights demonstrators, winning Supreme Circuit Court victory in Garner v. Louisiana; nominated to Second Court of Appeals by President Kennedy

1961 - Appointed circuit judge, makes 112 rulings, all of them later upheld by Supreme Court (1961-1965)

1965 - Appointed United States solicitor general by President Lyndon B. Johnson; wins 14 of the 19 cases he argues for the government (1965-1967)

1967 - Becomes first African-American elevated to U.S. Supreme Court (1967-1991)

1991 - Retires from the Supreme Court

1993 - Dies at age 84 in Bethesda, Maryland, near Washington, D.C.

Dedications

- The University of Maryland School of Law, which Marshall fought to desegregate, renamed and dedicated its law library in his honor.

- The University of California, San Diego has named one of its colleges after Thurgood Marshall.

- On February 14, 1976, the law school at Texas Southern University was formally named The Thurgood Marshall School of Law.[2] The school's mission is to "significantly impact the diversity of the legal profession."

- On October 1, 2005, Baltimore-Washington International Airport was renamed Baltimore-Washington Thurgood Marshall International Airport in his honor.

Notes

- ↑ ThisNation.com—What is a recess appointment? ThisNation.com. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- ↑ Texas Southern University: Thurgood Marshall School of Law. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beito, David T. and Linda Royster Beito. “T.R.M. Howard: Pragmatism over Strict Integrationist Ideology in the Mississippi Delta, 1942-1954” in Glenn Feldman (ed.), Before Brown: Civil Rights and White Backlash in the Modern South, pp. 68-95. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2004. ISBN 0817351345

- Williams, Juan. Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1998. ISBN 0812932994

| Preceded by: New seat |

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Judge 1962-1965 |

Succeeded by: Wilfred Feinberg |

| Preceded by: Archibald Cox |

Solicitor General of the United States 1965 – 1967 |

Succeeded by: Erwin N. Griswold |

| Preceded by: Tom C. Clark |

List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States October 2, 1967 – October 1, 1991 |

Succeeded by: Clarence Thomas |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.