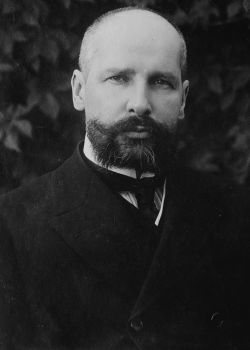

Pyotr Stolypin

| Pyotr Stolypin | |

| |

Third Prime Minister of Imperial Russia

| |

| In office July 21, 1906 – September 18, 1911 | |

| Preceded by | Ivan Goremykin |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Vladimir Kokovtsov |

| Born | 1862 Dresden |

| Died | 1911 Kiev |

| Spouse | Olga Borisovna Neidhardt |

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin (Russian: Пётр Арка́дьевич Столы́пин) (April 14 [O.S. April 2] 1862 – September 18 [O.S. September 5] 1911) served as Nicholas II's Chairman of the Council of Ministers—the Prime Minister of Russia—from 1906 to 1911. His tenure was marked by efforts to repress revolutionary groups, as well as for the institution of noteworthy agrarian reforms. Stolypin hoped, through his reforms, to stem peasant unrest by creating a class of market-oriented smallholding landowners. He is often cited as one of the last major statesmen of Imperial Russia with a clearly defined political program and determination to undertake major reforms.

After his assassination in 1911, the country muddled through the next several years until the outbreak of World War I, which would ultimately strike the death knell for the autocratic regime of Tsar Nicholas. The failure to implement meaningful reform and bring Russia into the modern political and economic system combined with the pressures of the regime's failures in the war gave rise to the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Family and background

Stolypin was born in Dresden, Saxony, on April 14, 1862. His family was prominent in the Russian aristocracy; Stolypin was related on his father's side to the famous Romantic poet, Mikhail Lermontov. His father was Arkady Dmitrievich Stolypin (1821-1899), a Russian landowner, descendant of a great noble family, a general in the Russian artillery and later Commandant of the Kremlin Palace. His mother was Natalia Mikhailovna Stolypina (née Gorchakova; 1827-1889), the daughter of a Russian foreign minister Alexander Mikhailovich Gorchakov. He received a good education in St. Petersburg University and began his service in government upon graduating in 1885 when he joined the Ministry of State Domains. Four years later Stolypin was appointed marshal of Kovno province.[1]

In 1884, Stolypin married Olga Borisovna Neidhardt, the daughter of a prominent Muscovite family, with whom he had five daughters and a son.[2]

Governor and Interior Minister

In 1902 Stolypin was appointed governor in Grodno, where he was the youngest person ever appointed to the position. He next became governor of Saratov, where he became known for the suppression of peasant unrest in 1905, gaining a reputation as the only governor who was able to keep a firm hold on his province in this period of widespread revolt. Stolypin was the first governor to use effective police methods against those who might be suspected of causing trouble, and some sources suggest that he had a police record on every adult male in his province.[3] His successes as provincial governor led to Stolypin's appointment interior minister under Ivan Goremykin.

Prime Minister

A few months later, Nicholas II appointed Stolypin to replace Goremykin as Prime Minister. Stolypin's strategy was two-fold. The first part was to quell the political unrest. Russia in 1906 was plagued by revolutionary unrest and wide discontent among the population. Socialist and other radical organizations were waging campaigns against the autocracy, and had wide support; throughout Russia, police officials and bureaucrats were targeted for assassination. To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system that allowed for the arrest and speedy trial of accused offenders. Over 3000 suspects were convicted and executed by these special courts between 1906-1909.[1] The gallows used for hanging hence acquired the nickname "Stolypin's necktie."

The second part of his plan was to create rich stakeholders. To help quell dissent, Stolypin also hoped to remove some of the causes of grievance among the peasantry. He aimed to create a moderately wealthy class of peasants, those who would be supporters of societal order.[4] Thus, he introduced important land reforms. Stolypin also tried to improve the lives of urban laborers and worked towards increasing the power of local governments. He dissolved the First Duma on July 22 [O.S. July 9] 1906, after the reluctance of some of its more radical members to co-operate with the government and calls for land reform. (see below)

End of his tenure

Stolypin changed the nature of the Duma to attempt to make it more willing to pass legislation proposed by the government.[5] After dissolving the Second Duma in June 1907, he changed the weight of votes more in favor of the nobility and wealthy, reducing the value of lower class votes. This affected the elections to the Third Duma, which returned much more conservative members, more willing to co-operate with the government.

In the spring of 1911, Stolypin proposed a bill spreading the system of zemstvo to the southwestern provinces of Russia. It was originally slated to pass with a narrow majority, but Stolypin's partisan foes had it defeated. Afterwards he resigned as Prime Minister of the Third Duma.

Vladimir Lenin, head of the Bolshevik Party, was afraid Stolypin might succeed in helping Russia avoid a violent revolution. Many German political leaders feared that a successful economic transformation of Russia would undermine Germany's dominating position in Europe within a generation. Some historians believe that German leaders in 1914 chose to provoke a war with Tsarist Russia, in order to defeat it before it would grow too strong.

On the other hand, the Tsar did not give Stolypin unreserved backing. His position at Court may have already been seriously undermined by the time he was assassinated in 1911. Stolypin's reforms did not survive the turmoil of World War I, the October Revolution nor the Russian Civil War.

Assassination

In September 1911, Stolypin travelled to Kiev, despite prior police warnings that there was an assassination plot. He travelled without bodyguards and even refused to wear his bullet-proof vest.

On September 14 [O.S. September 1] 1911, while attending a performance of Rimsky-Korsakov's "The Tale of Tsar Saltan" at the Kiev Opera House in the presence of the Tsar and his family, Stolypin was shot twice, once in the arm and once in the chest, by Dmitri Bogrov, who was both a radical and agent of Okhrana, the Tsar's secret police. After being shot Stolypin was reported to have casually stood up from his chair, carefully removing his gloves and unbuttoning his jacket, and unveiled a blood-soaked waistcoast. He purportedly sank into his chair and shouted 'I am happy to die for the Tsar' before motioning to the Tsar in his royal box to withdraw to safety. Tsar Nicholas remained in his position and in one last theatrical gesture Stolypin blessed him with a sign of the cross. Stolypin died four days later. The following morning a resentful Tsar knelt at his hospital bedside and repeated the words 'Forgive me'. Bogrov was hanged ten days after the assassination, and the judicial investigation was halted by order of Tsar Nicholas. This led to suggestions that the assassination was planned not by leftists, but by conservative monarchists who were afraid of Stolypin's reforms and his influence on the Tsar, though this has never been proved.

Stolypin reform

The Stolypin agrarian reforms were a series of changes to Imperial Russia's agricultural sector instituted while he was Chairman of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister). Most if not all of these reforms were based on recommendations from a committee known as the "Needs of Agricultural Industry Special Conference," which was held in Russia between 1901-1903 during the tenure of Minister of Finance Sergei Witte.[6]

Background to reforms

The goal of the reform was to transform the traditional obshchina form of Russian agriculture, which bore some similarities to the open field system of Britain. Serfs who had been liberated by the emancipation reform of 1861 lacked the financial ability to leave their new lands, as they were indebted to the state for periods of up to 49 years.[7] Among the drawbacks of the obshchina system were collective ownership, scattered land allotments based on family size, and a significant level of control by the family elder. Stolypin, a staunch conservative, also sought to eliminate the commune system—known as the mir—and to reduce radicalism among the peasants, preventing further political unrest, such as that which occurred during the Russian Revolution of 1905. Stolypin believed that tying the peasants to their own private land holdings would produce profit-minded and politically conservative farmers like those found in parts of Western Europe.[8] Stolypin referred to his own programs as a "wager on the strong and sober."[9]

The reforms began with the introduction of the unconditional right of individual landownership (Ukase of November 9, 1906). Stolypin's reforms abolished the obshchina system and replaced it with a capitalist-oriented form highlighting private ownership and consolidated modern farmsteads.

The reforms were multifaceted and introduced the following:

- Development of large-scale individual farming (khutors)

- Introduction of agricultural cooperative

- Development of agricultural education

- Dissemination of new methods of land improvement

- Affordable lines of credit for peasants

- Creation of an Agrarian Party, to represent the interests of farmers

The Stolypin agrarian reforms were implemented by the state in a comprehensive campaign from 1906 through 1914. This system was not a command economy like that found in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, but rather a continuation of the modified state capitalism program begun under Sergei Witte. It was different from Witte's reforms not by the rapid push—a characteristic also found in the Witte reforms—but by the fact that Stolypin's reforms were to the agricultural sector, included improvements to the rights of individuals on a broad level and had the backing of the police. These reforms laid the groundwork for a market-based agricultural system for Russian peasants.

The principal ministers involved in the implementation of the reforms were Stolypin as Interior Minister and Prime Minister, Alexander Krivoshein as Agriculture and State Domains Minister, and Vladimir Kokovtsov as Finance Minister and Stolypin's successor as Prime Minister.

The Stolypin reforms and the majority of their benefits were reversed by the Soviet agrarian program in the 1920s.

Effects of reforms on Siberian resettlement

As a result of the expansion of the Trans-Siberian Railroad and other railroads east of the Ural Mountains and the Caspian Sea, migration to Siberia increased. Thompson estimated that between 1890 and 1914 that over ten million persons migrated freely from western Russia to areas east of the Urals.[10] This was encouraged by the Trans-Siberian Railroad Committee, which was personally headed by Tsar Nicholas II. The Stolypin agrarian reforms included resettlement benefits for peasants who moved to Siberia. Migrants received a small state subsidy, exemption from some taxes, and received advice from state agencies specifically developed to help with peasant resettlement.[11]

In part due to these initiatives, approximately 2.8 of the 10 million migrants to Siberia relocated between 1908 and 1913. This increased the population of the regions east of the Urals by a factor of 2.5 before the outbreak of World War I.

Cooperative initiatives

A number of new types of cooperative assistance were developed as part of the Stolypin agrarian reforms, including financial-credit cooperation, production cooperation, and consumer cooperation. Many elements of Stolypin's cooperation-assistance programs were later incorporated into the early agrarian programs of the Soviet Union, reflecting the lasting influence of Stolypin.

Legacy

Opinions about Stolypin's work were divided. In the unruly atmosphere after the Russian Revolution of 1905 he had to suppress violent revolt and anarchy. His agrarian reform held out much promise, however. Stolypin's phrase that it was a "wager on the strong" has often been maliciously misrepresented. Stolypin and his collaborators (most prominently his Minister of Agriculture Alexander Krivoshein and the Danish-born agronomist Andrei Andreievich Køfød) tried to give as many peasants as possible a chance to raise themselves out of poverty by promoting consolidation of scattered plots, introducing banking facilities for peasants and stimulating emigration from the overcrowded western areas to virgin lands in Kazakhstan and Southern Siberia. However, much of what Stolypin wished to accomplish remained unfulfilled at the time of the Russian Revolution of 1917, and afterwards were rolled back by the Soviet policy of Collectivization.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Peter Stolypin Spartacus Educational. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Arnold Blumberg, Great Leaders, Great Tyrants?: Contemporary Views of World Rulers Who Made History (Greenwood Press, 1995, ISBN 0313287511), 302.

- ↑ Peter Stolypin History learning Site. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Sir John Maynard, Russia in Flux: Before the October Revolution (Hassell Street Press, 2021, (original 1941), ISBN 978-1014363275).

- ↑ Peter Oxley, Russia, 1855 - 1991: From Tsars to Commissars (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0199134189).

- ↑ P.A. Stolypin and the Attempts of Reforms Russia the Great. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, A History of Russia, sixth ed. (Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0195121791), 373.

- ↑ John M. Thompson, A Vision Unfulfilled: Russia and the Soviet Union in the Twentieth Century (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1996, ISBN 066928291X), 83-85.

- ↑ Riasanovsky, 414.

- ↑ Thompson, 83-85.

- ↑ Riasanovsky, 432.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ascher, Abraham. P. A. Stolypin: The Search for Stability in Late Imperial Russia. Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780804739771

- Blumberg, Arnold. Great Leaders, Great Tyrants?: Contemporary Views of World Rulers Who Made History. Greenwood Press, 1995. ISBN 0313287511

- Maynard, Sir John. Russia in Flux: Before the October Revolution. Hassell Street Press, 2021, (original 1941). ISBN 978-1014363275

- Oxley, Peter. Russia, 1855 - 1991: From Tsars to Commissars. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0199134189

- Pallot, Judith. Land Reform in Russia, 1906-1917: Peasant Responses to Stolypin's Project of Rural Transformation. Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1999. ISBN 0198206569

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. A History of Russia, sixth ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0195121791

- Thompson, John M. A Vision Unfulfilled: Russia and the Soviet Union in the Twentieth Century. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1996. ISBN 066928291X

| Preceded by: Petr Nikolayevich Durnovo |

Minister of Interior July 1904 – February 1905 |

Succeeded by: Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Makarov |

| Preceded by: Ivan Goremykin |

Prime Minister of Russia July 21 1906—September 18 1911 |

Succeeded by: Vladimir Kokovtsov |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.