Portuguese Colonial War

The Portuguese Colonial War, also known as the Overseas War in Portugal or in the former colonies as the War of Liberation, was fought between Portugal’s military and the emerging nationalist movements in Portugal's African colonies between 1961 and 1974. Unlike other European nations, the Portuguese regime did not leave its African colonies, or the overseas provinces (províncias ultramarinas), during the 1950s and 1960s. During the 1960s, various armed independence movements, most prominently led by communist-led parties who cooperated under the Conference of Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies umbrella and pro U.S. groups, became active in these areas, most notably in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea. Atrocities were committed by all forces involved in the conflict. Combined guerrilla forces fighting under different parties in Mozambique succeeded in their rebellion. This was not because they won the war, but because elements of the Portuguese Armed Forces staged a coup in Lisbon in April 1974, overthrowing the government in protest against the cost and length of the war.

The revolutionary Portuguese government withdrew its remaining colonial forces and agreed a quick handover of power for the nationalistic African guerrillas. The end of the war resulted in the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Portuguese citizens, including military personnel, of European, African, and mixed ethnicity from the newly-independent African territories of Portugal. Over 1 million Portuguese or persons of Portuguese descent left these former colonies. Devastating civil wars also followed in Angola and Mozambique, which lasted several decades and claimed millions of lives and refugees. Portuguese colonialism—like almost all forms of colonial domination—was exploitative and oppressive. In joining the world family of nation-states following independence, the former Portuguese colonies realized their political and human rights for freedom and for self-determination. The departing colonial power, however, left behind economies designed to benefit Portugal not Africans and had equipped few Africans to lead their own state, having resisted granting independence for decades. For some, the viability of the nation-state (almost always a self-interested entity) is a matter of debate. As more people gain the liberty to determine their own futures, some hope that a new world order might develop, with the nation state receding in significance, enabling global institutions to consider the needs of the planet and of all its inhabitants.

Political context

Following World War II the two great powers, the United States and the Soviet Union sought to expand the sphere of influence and encouraged—both ideologically, financially and militarily—the formation of either pro Soviet Union or pro United States resistance groups. The United States supported the UPA in Angola. The UPA (terrorist group), which was based in the Congo, would attack and massacre Portuguese settlers and local Africans living in Angola from bases in the Congo. The photos of these massacres which included photos of decapitated women and children (both of European and Angolan origin) would later be displayed in the UN. It is rumored that the then U.S. president John F Kennedy sent a message to Salazar to leave the colonies shortly after the massacre. Salazar, after a pro U.S. coup failed to depose him, consolidated power and immediately set to protect the overseas territories by sending reinforcements and so the war would begin in Angola (similar scenarios would play out in all other overseas Portuguese territories).

It is in this context that the Asian-African Conference was held in Bandung, Indonesia in 1955. The conference presented a forum for the colonies, most of them newly independent and facing the same problem—pressure to align with one or the other Cold War superpower in the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. At the conference the colonies were presented with an alternative. They could band together as the so-called Third World and work both to preserve the balance of power in Cold War relations and to use their new sense of independence for their own benefit by becoming an influence zone of their own. This would lessen the effect of the colonial and neo-colonial powers on the colonies, and increased their sense of unity and desire to support each other in their relationships with the other powers.

In the late 1950s, the Portuguese Armed Forces saw themselves confronted with the paradox generated by the dictatorial regime of Estado Novo that had been in power since 1926: on the one hand, the policy of Portuguese neutrality in World War II placed the Portuguese Armed Forces out of the way of a possible East-West conflict; on the other hand, the regime felt the increased responsibility of keeping Portugal's vast overseas territories under control and protect the populations there. Portugal, a neutral country in the war against Germany (1939–1945) before the foundation of NATO, joined that organization as a founding member in 1949, and was integrated within the military commands of NATO. The NATO focus against the threat of a conventional Soviet attack against Western Europe was to the detriment of military preparations against guerrilla uprisings in Portugal's overseas provinces that were considered essential for the survival of the nation. The integration of Portugal in the Atlantic Alliance would form a military elite that would become essential during the planning and implementation of the operations during the Overseas War. This "NATO generation" would ascend quickly to the highest political positions and military command without having to provide evidence of loyalty to the regime. The Colonial War would establish, in this way, a split between the military structure—heavily influenced by the western powers with democratic governments—and the political power of the regime. Some analysts see the "Botelho Moniz coup" (also known as A Abrilada) against the Portuguese government and backed by the U.S. administration, as the beginning of this rupture, the origin of a lapse on the part of the regime to keep up a unique command center, an armed force prepared for threats of conflict in the colonies. This situation would cause, as would be verified later, a lack of coordination between the three general staffs (Army, Air Force, and Navy).

Armed conflict

The conflict began in Angola on 4 February 4, 1961, in an area called the Zona Sublevada do Norte (ZSN or the Rebel Zone of the North), consisting of the provinces of Zaire, Uíge and Cuanza Norte. The U.S.-backed UPA wanted national self-determination, while for the Portuguese, who had settled in Africa and ruled considerable territory since the fifteenth century, their belief in a multi-racial, assimilated overseas empire justified going to war to prevent its breakup. Portuguese leaders, including Salazar, defended the policy of multiracialism, or Lusotropicalism, as a way of integrating Portuguese colonies, and their peoples, more closely with Portugal itself. In Portuguese Africa, trained Portuguese black Africans were allowed to occupy positions in several occupations including specialized military, administration, teaching, health and other posts in the civil service and private businesses, as long as they had the right technical and human qualities. In addition, intermarriage with white Portuguese was a common practice since the earlier contacts with the Europeans. The access to basic, secondary and technical education was being expanded and its availability was being increasingly opened to both the indigenous and European Portuguese of the territories. Examples of this policy include several black Portuguese Africans who would become prominent individuals during the war or in the post-independence, and who had studied during the Portuguese rule of the territories in local schools or even in Portuguese schools and universities in the mainland (the metropole)—Samora Machel, Mário Pinto de Andrade, Marcelino dos Santos, Eduardo Mondlane, Agostinho Neto, Amílcar Cabral, Joaquim Chissano, and Graça Machel are just a few examples. Two large state-run universities were founded in Portuguese Africa in the 1960s (the Universidade de Luanda in Angola and the Universidade de Lourenço Marques in Mozambique, awarding a wide range of degrees from engineering to medicine, during a time that in the European mainland only four public universities were in operation, two of them in Lisbon (which compares with the 14 Portuguese public universities today). One of the most idolized sports stars in Portuguese history, a black football player from [[Portuguese East Africa named Eusébio, is another clear example of assimilation and multiracialism in the Portuguese Africa.

Because most policies and development plans were primarily designed by the ruling authorities of Portuguese Africa for the benefit of the Portuguese populations, little attention was paid to local tribal integration and the development of the native African communities. This affected a majority of the indigenous population who suffered both state-sponsored discrimination and enormous social pressure. Many felt they had received too little opportunity or resources to upgrade their skills and improve their economic and social situation to a degree comparable to that of the Europeans.

The UPA which was based in Zaire entered Angola and proceeded to massacre the civilian population (women and children included and of both European and Angolan African descent) under the full knowledge of the U.S. Government. John F. Kennedy would later notify António de Oliveira Salazar (via the U.S. consulate in Portugal) to immediately abandon the colonies. A U.S.-backed coup which would be known as the Abrilada was also attempted to overthrow the Estado Novo. It is due to this failed coup that Salazar was able to consolidate power and finally send a military response to the massacres occurring in Angola. As the war progressed, Portugal rapidly increased its mobilized forces. Under the dictatorship, a highly militarized population was maintained where all the males were obliged to serve three years in military service, and many of those called-up to active military duty were deployed to combat zones in Portugal's African overseas provinces. In addition, by the end of the Portuguese colonial war, in 1974, black African participation had become crucial, representing about half of all operational colonial troops of Portugal. By the early 1970s, it had reached the limit of its military capacity but at this stage the war was already won. The military threat was so minor at the later stages that immigration to Angola and Mozambique was actually increasing, as were the economies of the then Portuguese territories.

The guerrilla war was almost won in Angola, shifting to near total war in Guinea (although the territory was still under total control of the Portuguese military), and worsening in the north of Mozambique. According to Tetteh Hormeku (Programme Officer with Third World Network's Africa Secretariat in Accra; 2008 North-South Institute's Visiting Helleiner Research Fellow), the U.S. was so certain that the Portuguese presence in Africa was guaranteed that it was completely caught by surprise by the effects of the Carnation revolution,[1] causing it to hastily join forces with South Africa. This led to the invasion of Angola by South Africa shortly afterward.

The Portuguese having been in Africa for much longer than the other colonial empires had developed strong relations with the local people and therefore was able to win them over. Without this support the U.S. soon stopped backing the dissident groups in Angola.

The Soviet Union realizing that a military solution it had so successfully employed in several other countries around the world was not bearing fruit, dramatically changed strategy.[2] It focused instead on Portugal. With the growing popular discontent over the casualties of the war and due to the large economic divide between the rich and poor the communists were able to manipulate junior officers of the military. In early 1974, the war was reduced to sporadic guerrilla operations against the Portuguese in non-urbanized countryside areas far way from the main centers. The Portuguese have secured all cities, towns, and villages in Angola and Mozambique, protecting its white, black and mixed race populations from any sort of armed threat. A sound environment of security and normality was the norm in almost all Portuguese Africa. The only exception was Guinea-Bissau, the smallest of all continental African territories under Portuguese rule, where guerrilla operations, strongly supported by neighboring allies, managed to have higher levels of success.

A group of military officers under the influence of communists, would proceed to over throw the Portuguese government with what was later called the Carnation Revolution on April 25, 1974, in Lisbon, Portugal. This led to a period of economic collapse and political instability. In the following years, the process improved as stability returned in a couple of years, a democratic government was installed and later with Portugal entering the European Union in 1986, higher levels of political and economic stability were gradually achieved.

Angola

In Angola, the rebellion of the ZSN was taken up by the União das Populações de Angola (UPA), which changed its name to National Liberation Front of Angola (Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA)) in 1962. On February 4, 1961, the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola took credit for the attack on the prison of Luanda, where seven policemen were killed. On March 15, 1961, the UPA, in an attack, started the massacre of white populations and black workers. This region would be retaken by large military operations that, however, would not stop the spread of the guerrilla actions to other regions of Angola, such as Cabinda, the east, the southeast and the central plateaus.

Portugal's counterinsurgency campaign in Angola was clearly the most successful of all its campaigns in the Colonial War. By 1974, for a variety of reasons, it was clear that Portugal was winning the war in Angola. Angola is a relatively large African nation, and the long distances from safe haven in neighboring countries supporting the rebel forces made it difficult for the latter to escape detection (the distance from the major Angolan urban centers to the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia) were so far that the east part of the country was called Terras do Fim do Mundo ("Lands of the End of the World") by the Portuguese. Another factor was that the three nationalist groups FNLA, the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angogla (MPLA]], and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), spent as much time fighting each other as they did fighting the Portuguese. Strategy also played a role; General Costa Gomes's insistence that the war was to be fought not just by the military, but also involving civilian organizations led to a successful hearts and minds campaign against the influence of the various revolutionary movements. Finally, unlike other overseas departments, Portugal was able to receive support from South Africa in its Angolan campaign; Portuguese forces sometimes referred to their South African counter-insurgent counterparts as primos (cousins).

The campaign in Angola saw the development and initial deployment of several unique and successful counter-insurgency forces:

- Batalhões de Caçadores Pára-quedistas (Paratrooper Hunter Battalions): Employed throughout the conflicts in Africa, were the first forces to arrive in Angola when the war began

- Comandos (Commandos): Born out of the war in Angola, and later used in Guinea and Mozambique

- Caçadores Especiais (Special Hunters): Were in Angola from the start of the conflict in 1961

- Fiéis (Faithfuls): A force composed by Katanga exiles, black soldiers that opposed the rule of Mobutu Sese Seko

- Leais (Loyals): A force composed by exiles from Zambia, black soldiers that were against Kenneth Kaunda

- Grupos Especiais (Special Groups): Units of volunteer black soldiers that had commando training; also used in Mozambique

- Tropas Especiais (Special Troops): The name of Special Forces Groups in Cabinda

- Flechas (Arrows): A very successful unit, controlled by the Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado (PIDE), composed by Bushmen, that specialized in tracking, reconnaissance and pseudo-terrorist operations. They were the basis for the Rhodesian Selous Scouts. The Flechas were also employed in Mozambique.

- Grupo de Cavalaria Nº1 (1st Cavalry Group): A mounted cavalry unit, armed with the Heckler & Koch G3 rifle and Walther P-38 pistol, tasked with reconnaissance and patrolling. The 1st was also known as the "Angolan Dragoons" (Dragões de Angola). The Rhodesians would also later develop the concept of horse-mounted counter-insurgency forces, forming the Grey's Scouts.

- Batalhão de Cavalaria 1927 (1927 Cavalry Battalion): A tank unit equipped with the M5A1 tank. The battalion was used for supporting infantry forces and as a rapid reaction force. Again the Rhodesians would copy this concept forming the Rhodesian Armored Car Regiment.

Guinea-Bissau

In Guinea-Bissau, the Marxist African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) started fighting in January 1963. Its guerrilla fighters attacked the Portuguese headquarters in Tite, located to the south of Bissau, the capital, near the Corubal river. Similar actions quickly spread across the entire colony, requiring a strong response from the Portuguese forces.

The war in Guinea placed face to face Amílcar Cabral, the leader of PAIGC, and António de Spínola, the Portuguese general responsible for the local military operations. In 1965 the war spread to the eastern part of the country and in that same year the PAIGC carried out attacks in the north of the country where at the time only the minor guerrilla movement, the Front for the Liberation and Independence of Guinea (FLING), was fighting. By that time, the PAIGC started receiving military support from the Socialist Bloc, mainly from Cuba, a support that would last until the end of the war.

In Guinea, Portuguese troops initially took a defensive posture, limiting themselves to defending territories and cities already held. Defensive operations were particularly devastating to the regular Portuguese infantry who were regularly attacked outside of populated areas by the forces of the PAIGC. They were also demoralized by the steady growth of PAIGC liberation sympathizers and recruits among the rural population. In a relatively short time, the PAIGC had succeeded in reducing Portuguese military and administrative control of the country to a relatively small area of Guinea. Unlike the other colonial territories, successful small-unit Portuguese counterinsurgency tactics were slow to evolve in Guinea. Naval amphibious operations were instituted to overcome some of the mobility problems inherent in the underdeveloped and marshy areas of the country, utilizing Fuzileiro commandos as strike forces.

With some strategic changes by António Spínola in the late 1960s, the Portuguese forces gained momentum and, taking the offensive, became a much more effective force. In 1970, Portugal attempted to overthrow Ahmed Sékou Touré (with the support of Guinean exiles) in the Operação Mar Verde (Green Sea Operation). The objectives were: perform a coup d'etat in Guinea-Conakry; destroy the PAIGC naval and air assets; capture Amilcar Cabral and free Portuguese POWs held in Conakry. The operation was a failure, with only the POW rescue and the destruction of PAIGC ships being successful. Nigeria and Algeria offered support to Guinea-Conakry and the Soviet Union sent war ships to the area (known by NATO as the West Africa Patrol).

Between 1968 and 1972, the Portuguese forces took control of the situation and sometimes carried attacks against the PAIGC positions. At this time the Portuguese forces were also adopting unorthodox means of countering the insurgents, including attacks on the political structure of the nationalist movement. This strategy culminated in the assassination of Amílcar Cabral in January 1973. Nonetheless, the PAIGC continued to fight back and began to heavily press Portuguese defense forces. This became even more visible after PAIGC received heavy anti-aircraft cannon and other AA equipment provided by the Soviets, including SA-7 shoulder-launched anti-aircraft missiles, all of which seriously impeded Portuguese air operations.

The war in Guinea has been termed "Portugal's Vietnam." The PAIGC was well-trained, well-led, and equipped and received substantial support from safe havens in neighboring countries such as Senegal and Guinea-Conakry. The jungles of Guinea and the proximity of the PAIGC's allies near the border, were excellent to provide tactical superiority on cross-border attacks and resupplying missions for the guerrillas. This situation led to the Portuguese invasion of Guinea-Conakry in 1970—code named Operação Mar Verde.

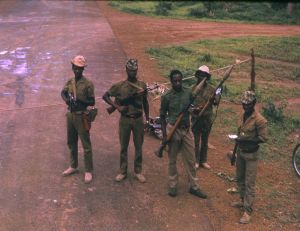

The war in Guinea also saw the use of two special units by the Portuguese Armed Forces:

- African Commandos (Comandos Africanos): Commando units entirely composed by black soldiers, including the officers

- African Special Marines (Fuzileiros Especiais Africanos): Marine units entirely composed by black soldiers

Mozambique

Mozambique was the last territory to start the war of liberation. Its nationalist movement was led by the Marxist-Leninist Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which carried out the first attack against Portuguese targets on September 24, 1964, in Chai, Cabo Delgado Province. The fighting later spread to Niassa, Tete, at the center of the country. A report from Battalion No. 558 of the Portuguese army makes references to violent actions, also in Cabo Delgado, on August 21, 1964.

On November 16, of the same year, the Portuguese troops suffered their first losses fighting in the north of the country, in the region of Xilama. By this time, the size of the guerrilla movement had substantially increased; this, along with the low numbers of Portuguese troops and colonists, allowed a steady increase in FRELIMO's strength. It quickly started moving south in the direction of Meponda and Mandimba, linking to Tete with the aid of Malawi.

Until 1967 the FRELIMO showed less interest in Tete region, putting its efforts on the two northernmost districts of the country where the use of landmines became very common. In the region of Niassa, FRELIMO's intention was to create a free corridor to Zambézia. Until April 1970, the military activity of FRELIMO increased steadily, mainly due to the strategic work of Samora Machel (later 1st President of Mozambique) in the region of Cabo Delgado.

The war in Mozambique saw a great involvement of Rhodesia, supporting the Portuguese troops in operations and even conducting operations independently. By 1973, the territory was mostly under Portuguese control. The Operation "Nó Górdio" (Gordian Knot Operation)—conducted in 1970 and commanded by Portuguese Brigadier General Kaúlza de Arriaga—a conventional-style operation to destroy the guerrilla bases in the north of Mozambique, was the major military operation of the Portuguese Colonial War. A hotly disputed issue, the Gordian Knot Operation was considered by several historians and military strategists as a failure that even worsened the situation for the Portuguese, but according to others, including its main architect, troops, and officials who had participated on both sides of the operation, including high ranked elements from the FRELIMO guerrilla, it was also globally described as a tremendous success of the Portuguese Armed Forces. Arriaga, however, was removed from his powerful military post in Mozambique by Marcelo Caetano shortly before the events in Lisbon that would trigger the end of the war and the independence of the Portuguese territories in Africa. The reason for Arriaga's abrupt fate was an alleged incident with indigenous civilian populations, as well as Portuguese government's suspicion that Arriaga was planning a military coup against Marcelo's administration in order to avoid the rise of leftist influences in Portugal and the loss of the African overseas provinces.

The construction of the Cahora Bassa Dam tied up large numbers of Portuguese troops (near 50 percent of all the troops in Mozambique) and brought the FRELIMO to the Tete Province, closer to some cities and more populated areas in the south. Still, although the FRELIMO tried to halt and stop the construction of the dam, it was never able to do so. In 1974, the FRELIMO launched mortar attacks against Vila Pery (now Chimoio) an important city and the first (and only) heavy populated area to be hit by the FRELIMO.

In Mozambique special units were also used by the Portuguese Armed Forces:

- Grupos Especiais (Special Groups): Locally-raised counter-insurgency troops similar to those used in Angola

- Grupos Especiais Pára-Quedistas (Paratrooper Special Groups): Units of volunteer black soldiers that were given airborne training

- Grupos Especiais de Pisteiros de Combate (Combat Tracking Special Groups): Special units trained in tracking and locating guerrillas forces

- Flechas (Arrows), a unit similar to the one employed in Angola

Role of the Organization of African Unity

The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was founded May 1963. Its basic principles were co-operation between African nations and solidarity between African peoples. Another important objective of the OAU was an end to all forms of colonialism in Africa. This became the major objective of the organization in its first years and soon OAU pressure led to the situation in the Portuguese colonies being brought up at the UN Security Council.

The OAU established a committee based in Dar es Salaam, with representatives from Ethiopia, Algeria, Uganda, Egypt, Tanzania, Zaire, Guinea, Senegal, and Nigeria, to support African liberation movements. The support provided by the committee included military training and weapon supplies.

The OAU also took action in order to promote the international acknowledgment of the legitimacy of the Revolutionary Government of Angola in Exile (GRAE), composed by the FNLA. This support was transferred to the MPLA and to its leader, Agostinho Neto in 1967. In November of 1972, both movements were recognized by the OAU in order to promote their merger. After 1964, the OAU recognized PAIGC as the legitimate representatives of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde and in 1965 recognized FRELIMO for Mozambique.

Armament and support

Portugal

When conflict erupted in 1961, Portuguese forces were badly equipped to cope with the demands of a counter-insurgency conflict. It was standard procedure, up to that point, to send the oldest and most obsolete material to the colonies. Thus, initial military operations were conducted using World War II radios, the old m/937 7,92 mm Mauser rifle, and the equally elderly German m/938 7,92mm (MG-13) Dreyse and Italian 8 mm x 59RB m/938 (Breda M37) machine guns.[3] Much of Portugal's older small arms derived from Germany in various deliveries made mostly before World War II. Later, Portugal would purchase arms and military equipment from France, West Germany, South Africa, and to a lesser extent, from Belgium, Israel, and the U.S.

Within a short time, the Portuguese Army saw the need for a modern selective-fire combat rifle, and in 1961 adopted the 7,62mm Espingarda m/961 (Heckler & Koch G3) as the standard infantry weapon for most of its forces.[4] However, quantities of the 7,62mm FN and German G1 FAL rifle, known as the m/962, were also issued; the FAL was a favored weapon of members serving in elite commando units such as the Caçadores Especiais.[4] At the beginning of the war, the elite airborne units (Caçadores Pára-quedistas) rarely used the m/961, having adopted the ultra-modern 7,62mm ArmaLite AR-10 in 1960. In the days before attached grenade launchers became standard, Portuguese paratroopers frequently resorted to the use of Energa rifle grenades fired from their AR-10 rifles. After Holland embargoed further sales of the AR-10, the paratroop battalions were issued a collapsible-stock version of the regular m/961 (G3) rifle, also in 7.62 mm NATO caliber.[5] For the machine-gun role, the German MG42 in 7.92mm and later 7.62mm NATO caliber was used until 1968, when the 7,62mm HK21 became available. Some 9mm x 19 mm submachine guns, including the German Steyr MP34 m/942, the Portuguese FBP m/948, and the Uzi were also used, mainly by officers, horse-mounted cavalry, reserve and paramilitary units, and security forces.[3]

To destroy enemy emplacements, other weapons were employed, including the 37 mm (1.46 in), 60 mm (2.5 in), and 89 mm (3.5 in.) Lança-granadas-foguete (Bazooka), along with several types of recoilless rifles.[6][5] Because of the mobile nature of counterinsurgency operations, heavy support weapons were less frequently used. However, the m/951 12.7 mm (.50 caliber) U.S. M2 Browning heavy machine gun saw service in both ground and vehicle mounts, as well as 60 mm, 81 mm, and later, 120 mm mortars.[6] Artillery and mobile howitzers were used in a few operations.

Mobile ground operations consisted of patrol sweeps by armored car and reconnaissance vehicles. Supply convoys used both armored and unarmored vehicles. Typically, armored vehicles would be placed at the front, center, and tail of a motorized convoy. Several Armored car armored cars were used, including the Panhard AML, Panhard EBR, Fox and (in the 70s) the Chaimite.

Unlike the Vietnam War, Portugal's limited national resources did not allow for widespread use of the helicopter. Only those troops involved in raids (also called golpe de mão (hand blow) in Portuguese)—mainly Commandos and Paratroopers—would deploy by helicopter. Most deployments were either on foot or in vehicles (Berliet and Unimog trucks). The helicopters were reserved for support (in a gunship role) or MEDEVAC (Medical Evacuation). The Alouette III was the most widely-used helicopter, although the Puma was also used with great success. Other aircraft were employed: for air support the T6 and the Fiat G.91 were used; for reconnaissance the Dornier Do 27 was employed. In the transport role, the Portuguese Air Force originally used the Junkers Ju 52, followed by the Nord Noratlas, the C-54 Skymaster, and the C-47 (all of these aircraft were also used for Paratroop drop operations).

The Portuguese Navy (particularly the Marines, known as Fuzileiros) made extensive use of patrol boats, landing craft, and Zodiac inflatable boats. They were employed especially in Guinea, but also in the Congo River (and other smaller rivers) in Angola and in the Zambezi (and other rivers) in Mozambique. Equipped with standard or collapsible-stock m/961 rifles, grenades, and other gear, they utilized small boats or patrol craft to infiltrate guerilla positions. In an effort to intercept infiltrators, the Fuzileiros even manned small patrol craft on Lake Malawi. The Navy also used Portuguese civilian cruisers as troop transports, and drafted Portuguese Merchant Navy personnel to man ships carrying troops and material.

Since 1961, with the beginning of the colonial wars in its overseas territories, Portugal had begun to incorporate black Portuguese Africans in the war effort in Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and Mozambique based on concepts of multi-racialism and preservation of the empire. African participation on the Portuguese side of the conflict varied from marginal roles as laborers and informers to participation in highly-trained operational combat units. As the war progressed, use of African counterinsurgency troops increased; on the eve of the military coup of April 25, 1974, Africans accounted for more than 50 percent of Portuguese forces fighting the war.

Guerrilla movements

The armament of the nationalist groups came mainly from the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and (especially in Mozambique) China. However, they also used small arms of U.S. manufacture (such as the .45 M1 Thompson submachine gun), along with British, French, and German weapons derived from neighboring countries sympathetic to the rebellion. Later in the war, most guerrillas would use roughly the same Soviet-origin infantry rifles: the Mosin-Nagant bolt-action rifle, the SKS carbine, and most importantly, the AK-47 series of 7,62mm x 39mm automatic rifles. Rebel forces also made extensive use of machine guns for ambush and positional defense. The 7,62mm Degtyarev light machine gun (LMG) was the most widely used LMG, together with the DShK and the SG-43 Goryunov heavy machine guns. Support weapons included mortars, recoilless rifles, and in particular, Soviet-made rocket-propelled grenade launchers, the RPG-2 and RPG-7. Anti-aircraft weapons were also employed, especially by the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) and the FRELIMO. The ZPU-4 AA cannon was the most widely used, but by far the most effective was the Strela 2 missile, first introduced to guerrilla forces in Guinea in 1973 and in Mozambique the following year by Soviet technicians.

The guerrillas' AK-47 and AKM rifles were highly thought of by many Portuguese soldiers, as they were shorter, slightly lighter, and more mobile than the m/961 (G3).[7] The AK-47's ammunition load was also lighter.[7] The average Angolan or Mozambiquan rebel carried 150 7,62mm x 39 cartridges (five 30-round magazines) as a combat load during bush operations, compared to 100 7,62mm x 51 rounds (five 20-round magazines) for the Portuguese infantryman on patrol.[7] Though a common misconception is that Portuguese soldiers used captured AK-47 type weapons, this was only true of a few elite units for special missions. Like U.S. forces in Vietnam, ammunition resupply difficulties and the danger of being mistaken for a guerrilla when firing an enemy weapon generally precluded their use.

Mines were one of the most successful weapons of the guerrilla movements, and the weapon most feared by Portuguese forces. The Portuguese used mine detection equipment, but also employed trained soldiers (picadors) walking abreast with long probes to detect nonmetallic road mines. All guerrillas used a variety of mines, combining anti-tank with anti-personnel mines with devastating results, frequently undermining the mobility of Portuguese forces. Other mines that were used includes the PMN (Black Widow), TM-46, and POMZ. Even amphibious mines were used such as the PDM, along with numerous home-made antipersonnel wood box mines and other nonmetallic explosive devices.

In general, the PAIGC in Guinea was the best armed, trained, and led of all the guerrilla movements. By 1970 it even had candidates training in the Soviet Union, learning to fly MiGs and to operate Soviet-supplied amphibious assault crafts and APCs.

Opposition

The government presented as a general consensus that the colonies were a part of the national unity, closer to overseas provinces than to true colonies. The communists were the first party to oppose the official view, since they saw the Portuguese presence in the colonies as an act against the colonies' right to self determination. During its 5th Congress, in 1957, the illegal Portuguese Communist Party (Partido Comunista Português—PCP) was the first political organization to demand the immediate and total independence of the colonies. However, being the only truly organized opposition movement, the PCP had to play two roles. One role was that of a communist party with an anti-colonialist position; the other role was to be a cohesive force drawing together a broad spectrum of opposing parties. Therefore it had to accede to views that didn't reflect its true anticolonial position.

Several opposition figures outside the PCP also had anticolonial opinions, such as the candidates to the fraudulent presidential elections, like Norton de Matos (in 1949), Quintão Meireles (in 1951) and Humberto Delgado (in 1958). The communist candidates had, obviously, the same positions. Among them were Rui Luís Gomes and Arlindo Vicente, the first would not be allowed to participate in the election and the second would support Delgado in 1958.

After the electoral fraud of 1958, Humberto Delgado formed the Independent National Movement (Movimento Nacional Independente—MNI) that, in October of 1960, agreed that there was a need to prepare the people in the colonies, before giving them the right of self-determination. Despite this, no detailed policies for achieving this goal were set out.

In 1961, the nº8 of the Military Tribune had as its title "Let's end the war of Angola." The authors were linked to the Patriotic Action Councils (Juntas de Acção Patriótica—JAP), supporters of Humberto Delgado, and responsible for the attack on the barracks of Beja. The Portuguese Front of National Liberation (Frente Portuguesa de Libertação Nacional—FPLN), founded in December 1962, attacked the conciliatory positions. The official feeling of the Portuguese state, despite all this, was the same: Portugal had inalienable and legitimate rights over the colonies and this was what was transmitted through the media and through the state propaganda.

In April 1964, the Directory of Democratic-Social Action (Acção Democrato-Social—ADS) presented a political solution rather than a military one. In agreement with this initiative in 1966, Mário Soares suggested there should be a referendum on the overseas policy Portugal should follow, and that the referendum should be preceded by a national discussion to take place in the six months prior to the referendum.

The end of Salazar's rule in 1968, due to illness, did not prompt any change in the political panorama. The radicalization of the opposition movements started with the younger people who also felt victimized by the continuation of the war.

The universities played a key role in the spread of this position. Several magazines and newspapers were created, such as Cadernos Circunstância, Cadernos Necessários, Tempo e Modo, and Polémica that supported this view. It was in this environment that the Armed Revolutionary Action (Acção Revolucionária Armada—ARA), the armed branch of the Portuguese Communist party created in the late 1960s, and the Revolutionary Brigades (Brigadas Revolucionárias—BR), a left-wing organization, became an important force of resistance against the war, carrying out multiple acts of sabotage and bombing against military targets. The ARA began its military actions in October of 1970, keeping them up until August of 1972. The major actions were the attack on the Tancos air base that destroyed several helicopters on March 8, 1971, and the attack on the NATO headquarters at Oeiras in October of the same year. The BR, on its side, began armed actions on November 7, 1971, with the sabotage of the NATO base at Pinhal de Armeiro, the last action being carried out April 9, 1974, against the Niassa ship which was preparing to leave Lisbon with troops to be deployed in Guinea. The BR acted even in the colonies, placing a bomb in the Military Command of Bissau on February 22, 1974.

Aftermath

In early 1974, the Portuguese had secured all cities, towns and villages in Angola and Mozambique, protecting its white, black and mixed race populations from any sort of armed threat. Vila Pery, Portuguese Overseas Province of Mozambique (now Chimoio, Mozambique) was the only heavily populated urban area which suffered a short-lived attack by terrorist guerrillas during the entire war. A sound environment of security and normality was the norm in almost all Portuguese Africa outside Guiné-Bissau. Economic growth and economic development in mainland Portugal and its overseas territories were at a record high during this period.

After a long period of economic divergence before 1914, the Portuguese economy recovered slightly until 1950, entering thereafter on a path of strong economic convergence. Portuguese economic growth in the period 1950–1973 created an opportunity for real integration with the developed economies of Western Europe. Through emigration, trade, tourism and foreign investment, individuals and firms changed their patterns of production and consumption, bringing about a structural transformation. Simultaneously, the increasing complexity of a growing economy raised new technical and organizational challenges, stimulating the formation of modern professional and management teams. However, Portuguese junior military officers, under the influence of the communists, would later successfully overthrow the Portuguese regime of Estado Novo in a bloodless military coup known as Carnation Revolution on April 25, 1974, in Lisbon. In Portugal this lead to a temporary communist government and a collapse of the economy. The communist government was soon overthrown and Portugal converted to a democratic government. But it would take 30 years and membership of the European Union for the Portuguese economy to recover from the effects of the Carnation revolution. The effects of having to integrate hundreds of thousand of refugees from the colonies (collectively known as retornados), nationalization of industries and the resultant brain drain due to political intimidation by the government of the entrepreneurial class would cripple the Portuguese economy for decades to come.

The war had a profound impact on Portugal—the use of conscription led to the illegal emigration of thousands of young men (mainly to France and the U.S.); it isolated Portugal internationally, effectively brought about the end of the Estado Novo regime and put an end to the 500 + years of Portuguese presence in Africa. Following a trend of the Portuguese, it was the military (the Movimento das Forças Armadas) who led the revolution, and for a brief time (May 1974-November 1975) the country was on the brink of civil war between left-wing hardliners (Vasco Gonçalves, Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho and others) and the moderate forces (Francisco da Costa Gomes, António Ramalho Eanes and others). The moderates eventually won, preventing Portugal from becoming a communist state.[8]

Portugal had been the first European power to establish a colony in Africa when it captured Ceuta in 1415 and now it was one of the last to leave. The departure of the Portuguese from Angola and Mozambique increased the isolation of Rhodesia, where white minority rule ended in 1980 when the territory gained international recognition as the Republic of Zimbabwe with Robert Mugabe as the head of government. The former Portuguese territories in Africa became sovereign states with Agostinho Neto (followed in 1979 by José Eduardo dos Santos) in Angola, Samora Machel (followed in 1986 by Joaquim Chissano) in Mozambique and Luís Cabral (followed in 1983 by Nino Vieira) in Guinea-Bissau, as heads of state.

The end of the war after the Carnation Revolution military coup of April 1974 in Lisbon, resulted in the exodus of thousands of Portuguese citizens, including military personnel, of European, African and mixed ethnicity from the newly-independent African territories to Portugal. Devastating civil wars also followed in Angola and Mozambique, which lasted several decades and claimed millions of lives and refugees. The former colonies became worse off after independence. Economic and social recession, corruption, poverty, inequality and failed central planning, eroded the initial impetus of nationalistic fervor. A level of economic development comparable to what had existed under Portuguese rule, became the goal of the independent territories. There was black racism in the former overseas provinces through the use of hatred against both ethnic Portuguese and many mulatto Africans. After departure of the Portuguese, and following independence, local soldiers that fought along with the Portuguese Army against the independence guerrillas were slaughtered by the thousands. A small number escaped to Portugal or to other African nations. The most famous massacre occurred in Bissorã, Guinea-Bissau. In 1980 PAIGC admitted in its newspaper "Nó Pintcha" (dated November 29, 1980) that many were executed and buried in unmarked collective graves in the woods of Cumerá, Portogole and Mansabá.

Economic consequences of the war

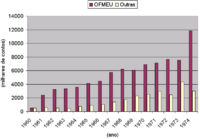

The Government budget increased significantly during the war years. The country's expenditure on the armed forces ballooned since the beginning of the war in 1961. The expenses were divided into ordinary and extraordinary ones; the latter were the main factor in the huge increase in the military budget. Since the rise of Marcelo Caetano, after Salazar's incapacitation, spending on military forces increased even further.

It is often stated that war in the colonies was having a severe impact but the accuracy of these statements have to be questioned. Especially in light of the vast natural resources of Angola. To put this in context prior to the Carnation Revolution—Angola was one of the largest oil producers in Africa. With the oil]] shock of 1974—oil alone could have easily paid for the war in all of the colonies. The former overseas provinces of Portugal in Africa, had a large variety of important natural resources like oil, natural gas, diamonds, aluminum, hydroelectric power capacity, forests, and fertile arable lands. In some areas of Portuguese Africa, these huge resource stock, despite its wide availability, was barely exploited by the early 1970s, but its potential future use was already anticipated by all parts involved in the conflict, including the world's Cold War superpowers. In fact, both oil extraction and diamond mining would play a huge financial and funding role in the decades long civil war that would cost millions of lives and refugees in post-independence Angola and which would primarily benefit the despotic post-independence rulers of the country, the U.S. (then Gulf Oil what is now called ChevronTexaco) and the Soviet Union.

The African territories became worse off after independence. The deterioration in [[central planning effectiveness, economic development and growth, security, education and health system efficiency, was rampant. None of the newly independent African States made any significant progress economically or social economically in the following decades. Almost all sank at the bottom of human development and GDP per capita world tables. After a few years, the former colonies had reached high levels of corruption, poverty, inequality, and social imbalances. In mainland Portugal, the coup itself was led by junior officers—which implies that the better informed senior officers did not believe the war was lost or that the economy was in severe crises. A further illustration would be to compare the economic growth rates of Portugal in the war years 6 percent to post war years 2-3 percent. This is substantially higher than the vast majority of other European nations (and much higher than what Portugal has actually been able to achieve after the war). Other indicators like GDP as percentage of Western Europe would indicate that Portugal was rapidly catching up to its European neighbors. It would take almost 30 years for Portugal reach the same level of GDP as a percentage of Western Europe GDP averages as it had during the war.

The impact of the military coup in Lisbon on the Portuguese economy in areas as diverse as shipping, chemical industry, finance, agriculture, mining and defense, was extremely negative. The communist inspired military coup and the chaotic abandonment of the Portuguese territories in Africa had a more severe, devastating and lasting impact on both Portugal and its overseas territories than the actual Colonial War. Without one single exception—all the overseas territories were economically and socially worse off after independence than prior to independence.

It would take several decades and joining of the European Community before the Portuguese economy would see any signs of recovering. To date, it has not matched growth rates achieved during the Colonial war.

Legacy

The former colonies became worse off after independence. Economic and social recession, corruption, poverty, inequality and failed central planning, eroded the initial impetus of nationalistic fervor. A level of economic development comparable to what had existed under Portuguese rule became the goal of the independent territories. However, under Portuguese rule, the infrastructures and the economies of the colonies were organized to benefit the colonial power, not the colonized. This was generally true of colonial powers, who had little interest in enabling colonies to become economically viable independently of the metropole. Nor did Portugal, fighting tenaciously to retain her colonies, do much to develop and train local leaders for the responsibilities of self-governance. The borders, too, of most African nation-states that emerged from the decolonization process had been created by the colonial powers. Often, the populations of these states had never had to co-operate in running and organizing a single political entity; often, different communities had lived within their own, smaller polities.

However, the UN has stated that "in the process of decolonization there is no alternative to the principle of self-determination, which is also a fundamental human right."[9] Colonialism was an exploitative and often oppressive phase in human maturation, and had to end so that people around the world could achieve their freedom. Yet, if the world is ever to become a place of peace for all people, a more equitably global economic system will have to be established. Some argue that because of neocolonialism many former colonies are not truly free but remain dependent on the world's leading nations. No one of principle wants to deny people their freedom, or perpetuate oppression, injustice and inequality. However, while many celebrate decolonization in the name of freedom and realization of the basic human rights of self-determination, others question whether equality, justice, peace, the end of poverty, exploitation and the dependency of some on others can be achieved as long as nation-states promote and protect their own interests, interests that are not always at the expense of others' but which often are. As freedom spreads around the world, as more people gain the liberty to determine their own futures, some people hope that a new world order might develop, with the nation state receding in significance. Instead, global institutions would consider the needs of the planet and of all its inhabitants.

Notes

- ↑ Tetteh Hormeku, US intervention in Africa: Through Angolan eyes, Third World Resurgence No. 89, January.

- ↑ CNN, Cuba-Angola letters, 1975. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Abbott and Rodrigues (1998), 17.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Afonso and Gomes (2000), 358-359.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Afonso and Gomes (2000), 183-184.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Abbott and Rodrigues (1998), 18.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Afonso and Gomes (2000), 266-267.

- ↑ Time, Western Europe's First Communist Country? Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ↑ Official Records of the General Assembly: Documents Officiels de L'Assemblée Générale (United Nations General Assembly, 2005), 204.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abbott, Peter, and Manuel Ribeiro Rodrigues. 1998. Modern African Wars 2. Angola and Moçambique 1961-74. Men-at-arms series, 202. London, UK: Osprey. ISBN 9780850458435.

- Afonso, Aniceto, and Carlos de Matos Gomes. 2000. Guerra Colonial. Lisboa, PT: Notícias Editorial. ISBN 9789724611921.

- Birmingham, David. 2006. Empire in Africa: Angola and its Neighbors. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780896802483.

- Bruce, Neil F. 1975. Portugal, the Last Empire. New York, NY: Wiley. ISBN 9780470113660.

- Cann, John P. 1997. Counterinsurgency in Africa the Portuguese way of War, 1961-1974. Contributions in military studies, no. 167. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313046575.

- Ferreira, Carolin Overhoff. 2005. Decolonizing the mind? The representation of the African Colonial War in Portuguese cinema. Studies in European Cinema. 2(3):227-239.

- Newitt, M.D.D. 1981. Portugal in Africa: The Last Hundred Years. London, UK: Longman. ISBN 9780582643796.

- Pakenham, Thomas. 1991. The Scramble for Africa, 1876-1912. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 9780394515762.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.