Difference between revisions of "Phenylketonuria" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

* Epinephrine then is synthesized from norepinephrine via methylation of the primary distal amine of norepinephrine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT). | * Epinephrine then is synthesized from norepinephrine via methylation of the primary distal amine of norepinephrine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT). | ||

| − | The enzyme [[phenylalanine hydroxylase]] (PAH) is fundamental to the process through conversion of amino acid phenylalanine into the amino acid tyrosine. This is the only known | + | The enzyme [[phenylalanine hydroxylase]] (PAH) is fundamental to the process through conversion of amino acid phenylalanine into the amino acid tyrosine. This is the only known role of PAH in the human body (Krapp and Wilson 2005). |

[[Image:PKU.PNG|center|500px|thumb|Simplified pathway for phenylalanine metabolism]] | [[Image:PKU.PNG|center|500px|thumb|Simplified pathway for phenylalanine metabolism]] | ||

===Phenylketonuria=== | ===Phenylketonuria=== | ||

| − | The enzyme phenylalananine hydroxylase (PAH) is necessary to break down phenylalanine. However, a genetic [[mutation]] in the gene that is necessary for producing PAH results in little, no, or poor quality enzyme being made. The gene for phenylalanine hydroxylase is found on [[chromosome]] 12 (Longe 2006). There are many different mutation sites, which can lead to a range of errors in thr enzyme, including lack of the enzyme (Longe 2006). | + | The enzyme phenylalananine hydroxylase (PAH) is necessary to break down phenylalanine. However, a genetic [[mutation]] in the [[gene]] that is necessary for producing PAH results in little, no, or poor quality enzyme being made. The gene for phenylalanine hydroxylase is found on [[chromosome]] 12 (Longe 2006). There are many different mutation sites, which can lead to a range of errors in thr enzyme, including lack of the enzyme (Longe 2006). |

| − | If, because of the lack of PAH, the reaction converting phenylalanine to tryrosine does not take place, then phenylalanine accumulates and tyrosine is deficient. Phenylketonuria is the inability to metabolize phenylalanine. | + | If, because of the lack of PAH, the reaction converting phenylalanine to tryrosine does not take place, then phenylalanine accumulates and tyrosine is deficient. Phenylketonuria is the inability to metabolize phenylalanine. Abnormally high levels of phenylalanine are toxic to cells of the [[nervous system]]. |

Excessive phenylalanine can be metabolized into phenylketones, which are detected in the urine. These include [[phenylacetate]], [[phenylpyruvate]], and [[phenylethylamine]] (Michals and Matalon 1985). Detection of phenylketones in the urine is diagnostic. | Excessive phenylalanine can be metabolized into phenylketones, which are detected in the urine. These include [[phenylacetate]], [[phenylpyruvate]], and [[phenylethylamine]] (Michals and Matalon 1985). Detection of phenylketones in the urine is diagnostic. | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

Phenylketonuria is an [[autosomal recessive]] genetic disorder. This means that a child must inherit abnormal genes from both parents to develop PKU (Longe 2006). People with one gene are carriers because they do not have the disease, but can pass it on to the their children. | Phenylketonuria is an [[autosomal recessive]] genetic disorder. This means that a child must inherit abnormal genes from both parents to develop PKU (Longe 2006). People with one gene are carriers because they do not have the disease, but can pass it on to the their children. | ||

| − | Children | + | Children appear normal at birth, but if not treated early will develop ''irreversible'' mental retardation (Longe 2006). |

== History == | == History == | ||

| − | Phenylketonuria was discovered by the [[Norwegians|Norwegian]] physician [[Ivar Følling]] in | + | Phenylketonuria was discovered by the [[Norwegians|Norwegian]] physician [[Ivar Følling]] in 1934 (Folling 1934), when he noticed that hyperphenylalaninemia (HPA) was associated with mental retardation. In Norway, this disorder is known as '''Følling's disease''', named after its discoverer (Centerwall and Centerwall 2000). |

| + | |||

| + | Dr. Følling was one of the first physicians to apply detailed chemical analysis to the study of disease. His careful analysis of the urine of two retarded siblings led him to request many physicians near Oslo to test the urine of other retarded patients. This led to the discovery of the same substance that he had found in eight other patients. The substance found was subjected to much more basic and rudimentary chemical analysis. He conducted tests and found reactions that gave rise to [[benzaldehyde]] and [[benzoic acid]], which led him to conclude the compound contained a [[benzene]] ring. Further testing showed the [[melting point]] to be the same as [[phenylpyruvic acid]], which indicated that the substance was in the urine. His careful science inspired many to pursue similar meticulous and painstaking research with other disorders. | ||

==Incidence and natural history== | ==Incidence and natural history== | ||

| Line 127: | Line 129: | ||

----------------------------------------------------------- —> | ----------------------------------------------------------- —> | ||

{{Reflist|2}} | {{Reflist|2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ref name="Folling">{{cite journal | author=Folling, A. | year=1934 | title=Ueber Ausscheidung von Phenylbrenztraubensaeure in den Harn als Stoffwechselanomalie in Verbindung mit Imbezillitaet | journal=Ztschr. Physiol. Chem. | volume=227 | pages=169-176}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ref>{{cite journal | author=Centerwall, S. A. & Centerwall, W. R. | year=2000 | title=The discovery of phenylketonuria: the story of a young couple, two retarded children, and a scientist. | url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/105/1/89 | journal=Pediatrics | volume=105 (1 Pt 1) | pages=89-103 | id=PMID 10617710}}</ref> | ||

* Joh, T. H., and O. Hwang. 1987. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=3473965&dopt=Abstract Dopamine beta-hydroxylase: Biochemistry and molecular biology]. ''Ann N Y Acad Sci.'' 493: 342-50. Retrieved August 2, 2007. | * Joh, T. H., and O. Hwang. 1987. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=3473965&dopt=Abstract Dopamine beta-hydroxylase: Biochemistry and molecular biology]. ''Ann N Y Acad Sci.'' 493: 342-50. Retrieved August 2, 2007. | ||

Revision as of 20:04, 3 August 2007

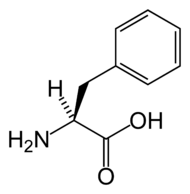

| Phenylketonuria Classification and external resources | |

| Phenylalanine | |

| ICD-10 | E70.0 |

| ICD-9 | 270.1 |

| OMIM | 261600 |

| DiseasesDB | 9987 |

| MedlinePlus | 001166 |

| eMedicine | ped/1787 derm/712 |

| MeSH | D010661 |

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a genetic disorder characterized by a deficiency in the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), which is necessary to metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine to the amino acid tyrosine. If untreated, phenylalanine accumulates and can result in neurological problems, including mental retardation and seizures. PKU is sometimes called Folling's disease. It is the most serious disorder of a class of diseases known as hyperphenylalaninemia, all of which involve elevated levels of phenylalanine in the blood (Krapp and Wilson 2005).

PKU is one of the few genetic diseases that can be controlled by diet, involving low consumption of phenylananine and a diet high in tyrosine.

Women affected by PKU must pay special attention to their diet if they wish to become pregnant, since high levels of phenylalanine in the uterine environment can cause severe malformation and mental retardation in the child. However, women who maintain an appropriate diet can have normal, healthy children.

The intricate coordination of systems in the human body is seen in the process, catalyzed by enzymes, by which l-phenylalanine is degraded into l-tyrosine, which in turn is converted into L-DOPA, which is further metabolized into other vitally important products: dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and epinephrine (adrenaline). However, in the advent of the lack of a particular enzyme due to a genetic effect, the harmony is disrupted and the body loses its ability to metabolize phenylalanine, resulting in the serious disorder phenylketonuria.

Overview

Phenylalanine

Phenylalanine is an α-amino acid that is found in many proteins (such as hemoglobin, is essential in the human diet, and normally is readily converted to the amino acid tyrosine in the human body.

In humans, the L-isomer of phenylalanine, which is the only form that is involved in protein synthesis, is one of the 20 standard amino acids common in animal proteins and required for normal functioning in humans. Phenylalanine also is classified as an "essential amino acid" since it cannot be synthesized by the human body from other compounds through chemical reactions and thus has to be taken in with the diet.

Metabolic pathways

L-phenylalanine can be converted into L-tyrosine, another one of the DNA-encoded amino acids. L-tyrosine in turn is converted into L-DOPA, which is further converted into dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and epinephrine (adrenaline). Dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine are known as catecholamines. Catecholamines are any of a group of amines (nitrogen-contain organic compounds) derived from the amino acid tyrosine and containing a catechol group (aromatic chemical compound consisting of a benzene ring with two hydroxyl groups). Catecholamine are important as neurotransmitters and hormones.

The basic synthetic pathway shared by all catecholamines involves the following series of enzymatic steps:

- Tryosine, one of the main precursors of catecholamines, is created from phenylalanine by hydroxylation via the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. (Tyrosine also is ingested directly from dietary protein).

- Tyrosine is oxidized into dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA).

- This is followed by decarboxylation into the neurotransmitter dopamine.

- Next is β-oxidation into norepinephrine by dopamine beta hydroxylase.

- Epinephrine then is synthesized from norepinephrine via methylation of the primary distal amine of norepinephrine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT).

The enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) is fundamental to the process through conversion of amino acid phenylalanine into the amino acid tyrosine. This is the only known role of PAH in the human body (Krapp and Wilson 2005).

Phenylketonuria

The enzyme phenylalananine hydroxylase (PAH) is necessary to break down phenylalanine. However, a genetic mutation in the gene that is necessary for producing PAH results in little, no, or poor quality enzyme being made. The gene for phenylalanine hydroxylase is found on chromosome 12 (Longe 2006). There are many different mutation sites, which can lead to a range of errors in thr enzyme, including lack of the enzyme (Longe 2006).

If, because of the lack of PAH, the reaction converting phenylalanine to tryrosine does not take place, then phenylalanine accumulates and tyrosine is deficient. Phenylketonuria is the inability to metabolize phenylalanine. Abnormally high levels of phenylalanine are toxic to cells of the nervous system.

Excessive phenylalanine can be metabolized into phenylketones, which are detected in the urine. These include phenylacetate, phenylpyruvate, and phenylethylamine (Michals and Matalon 1985). Detection of phenylketones in the urine is diagnostic.

Phenylalanine is a large, neutral amino acid (LNAA). LNAAs compete for transport across the blood brain barrier (BBB) via the large neutral amino acid transporter (LNAAT). Excessive phenylalanine in the blood saturates the transporter. Thus, excessive levels of phenylalanine significantly decrease the levels of other LNAAs in the brain. But since these amino acids are required for protein and neurotransmitter synthesis, phenylalanine accumulation disrupts brain development in children, leading to mental retardation (Pietz et al. 1999).

Since phenylalanine uses the same active transport channel as tryptophan to cross the blood-brain barrier, in large quantities it also interferes with the production of serotonin, which is a metabolic product of tryptophan.

Phenylketonuria is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder. This means that a child must inherit abnormal genes from both parents to develop PKU (Longe 2006). People with one gene are carriers because they do not have the disease, but can pass it on to the their children.

Children appear normal at birth, but if not treated early will develop irreversible mental retardation (Longe 2006).

History

Phenylketonuria was discovered by the Norwegian physician Ivar Følling in 1934 (Folling 1934), when he noticed that hyperphenylalaninemia (HPA) was associated with mental retardation. In Norway, this disorder is known as Følling's disease, named after its discoverer (Centerwall and Centerwall 2000).

Dr. Følling was one of the first physicians to apply detailed chemical analysis to the study of disease. His careful analysis of the urine of two retarded siblings led him to request many physicians near Oslo to test the urine of other retarded patients. This led to the discovery of the same substance that he had found in eight other patients. The substance found was subjected to much more basic and rudimentary chemical analysis. He conducted tests and found reactions that gave rise to benzaldehyde and benzoic acid, which led him to conclude the compound contained a benzene ring. Further testing showed the melting point to be the same as phenylpyruvic acid, which indicated that the substance was in the urine. His careful science inspired many to pursue similar meticulous and painstaking research with other disorders.

Incidence and natural history

The incidence of PKU is about 1 in 15,000 births, but the incidence varies widely in different human populations from 1 in 4,500 births among the population of Ireland[2] to fewer than one in 100,000 births among the population of Finland.[3]

PKU is normally detected using the Guthrie test, part of national biochemical screening programs.

If a child is not screened at birth (e.g. in home deliveries), the disease may present clinically with seizures, albinism (excessively fair hair and skin), and a "musty odor" to the baby's sweat and urine (due to phenylacetate, one of the ketones produced).

Untreated children are normal at birth, but fail to attain early developmental milestones, develop microcephaly, and demonstrate progressive impairment of cerebral function. Hyperactivity, EEG abnormalities and seizures, and severe mental retardation are major clinical problems later in life. A "musty" odor of skin, hair, sweat and urine (due to phenylacetate accumulation); and a tendency to hypopigmentation and eczema are also observed.

In contrast, affected children who are detected and treated at birth are less likely to develop neurological problems and have seizures and mental retardation, though such clinical disorders are still possible.

Pathophysiology

Classical PKU is caused by a defective gene for the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), which converts the amino acid phenylalanine to other essential compounds in the body. A rarer form of the disease occurs when PAH is normal but there is a defect in the biosynthesis or recycling of the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) by the patient.[4] This cofactor is necessary for proper activity of the enzyme. Other, non-PAH mutations can also cause PKU [5].

The PAH gene is located on chromosome 12 in band 12q23.2. More than four hundred disease-causing mutations have been found in the PAH gene.[6]. PAH deficiency causes a spectrum of disorders including classic phenylketonuria (PKU) and hyperphenylalaninemia (a less severe accumulation of phenylalanine).[7]

PKU is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder, meaning that each parent must have at least one defective allele of the gene for PAH, and the child must inherit two defective alleles, one from each parent. As a result, it is possible for a parent with PKU phenotype to have a child without PKU if the other parent possesses at least one functional allele of the PAH gene; but a child of two parents with PKU will always inherit two defective alleles, and therefore the disease.

Phenylketonuria can exist in mice, which have been extensively used in experiments into an effective treatment for PKU[8]. PKU is caused by a recessive allele located on chromosome # 12.

The macaque monkey's genome was recently sequenced, and it was found that the gene encoding phenylalanine hydroxylase has the same sequence which in humans would be considered the PKU mutation.

Treatment

If PKU is diagnosed early enough, an affected newborn can grow up with normal brain development, but only by eating a special diet low in phenylalanine for the rest of his or her life. This requires severely restricting or eliminating foods high in phenylalanine, such as breast milk, meat, chicken, fish, nuts, cheese and other dairy products. Starchy foods such as potatoes, bread, pasta, and corn must be monitored. Many diet foods and diet soft drinks that contain the sweetener aspartame must also be avoided, as aspartame consists of two amino acids: phenylalanine and aspartic acid.

Supplementary infant formulas are used in these patients to provide the amino acids and other necessary nutrients that would otherwise be lacking in a protein free diet. (Since phenylalanine is necessary for the synthesis of many proteins, it is required but levels must be strictly controlled. In addition, tyrosine, which is normally derived from phenylalanine, must be supplemented.)

In those patients with a deficit in BH4 production, or with a PAH PAH mutation resulting in a low affinity of PAH for BH4, treatment consists of giving BH4 as a supplement; this is referred to as BH4 responsive PKU.

There are a number of other therapies currently under investigation, including gene therapy, and an injectable form of PAH. However, it is likely that it will be many years before these are available for human use.

Treatment of PKU includes the elimination of phenylalanine from the diet, and supplementation of the diet with tyrosine. Phenylalanine is commonly found in protein-containing foods such as meat, dairy products, fish, grains and legumes. Babies who are diagnosed with PKU must immediately be put on a special milk/formula substitute. Later in life, the diet continues to exclude phenylalanine-containing foods.

Previously, PKU-affected people were allowed to go off diet after approximately 12 years of age. However, physicians now recommend that this special diet should be followed throughout life.

Maternal phenylketonuria

For women affected with PKU, it is essential for the health of their child to maintain low phenylalanine levels before and during pregnancy.[9] Though the developing fetus may only be a carrier of the PKU gene, the intrauterine environment can have very high levels of phenylalanine, which can cross the placenta. The result is that the child may develop congenital heart disease, growth retardation, microcephaly and mental retardation.[10] PKU-affected women themselves are not at risk from additional complications during pregnancy.

In most countries, women with PKU who wish to have children are advised to lower their blood phenylalanine levels before they become pregnant and carefully control their phenylalanine levels throughout the pregnancy. This is achieved by performing regular blood tests and adhering very strictly to a diet, generally monitored on day-to-day basis by a specialist metabolic dietitian. When low phenylalanine levels are maintained for the duration of pregnancy there are no elevated levels of risk of birth defects compared with a baby born to a non-PKU mother.[11]

Cultural references

The main character of the novel Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes is mentally retarded due to this disease.

See also

- Tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency

- For a thorough scientific overview of hyperphenylalaninemia, one can consult chapter 77 of OMMBID[12]. For more online resources and references, see inborn error of metabolism.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFolling - ↑ DiLella, A. G., Kwok, S. C. M., Ledley, F. D., Marvit, J., Woo, S. L. C. (1986). Molecular structure and polymorphic map of the human phenylalanine hydroxylase gene. Biochemistry 25: 743-749. PMID 3008810.

- ↑ Guldberg, P., Henriksen, K. F., Sipila, I., Guttler, F., de la Chapelle, A. (1995). Phenylketonuria in a low incidence population: molecular characterization of mutations in Finland. J. Med. Genet 32: 976-978. PMID 8825928.

- ↑ Surtees, R., Blau, N. (2000). The neurochemistry of phenylketonuria. European Journal of Pediatrics 169: S109-13. PMID 11043156.

- ↑ PKU 2007 Genetics of Phenylketonuria - A Comprehensive Review

- ↑ PKU 2007 Genetics of Phenylketonuria - A Comprehensive Review

- ↑ http://www.gene.ucl.ac.uk Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) gene summary, retrieved September 8, 2006

- ↑ Oh, H. J., Park, E. S., Kang, S., Jo, I., Jung, S. C. (2004). Long-Term Enzymatic and Phenotypic Correction in the Phenylketonuria Mouse Model by Adeno-Associated Virus Vector-Mediated Gene Transfer. Pediatric Research 56: 278-284. PMID 15181195.

- ↑ Lee, P.J., Ridout, D., Walker, J.H., Cockburn, F., (2005). Maternal phenylketonuria: report from the United Kingdom Registry 1978–97. Archives of Disease in Childhood 90: 143-146. PMID 15665165..

- ↑ Rouse, B., Azen, B., Koch, R., Matalon, R., Hanley, W., de la Cruz, F., Trefz, F., Friedman, E., Shifrin, H. (1997). Maternal phenylketonuria collaborative study (MPKUCS) offspring: Facial anomalies, malformations, and early neurological sequelae.. American Journal of Medical Genetics 69 (1): 89–95. PMID 9066890.

- ↑ lsuhsc.edu Genetics and Louisiana Families

- ↑ Charles Scriver, Beaudet, A.L., Valle, D., Sly, W.S., Vogelstein, B., Childs, B., Kinzler, K.W. (Accessed 2007). The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill. - Summaries of 255 chapters, full text through many universities. There is also the OMMBID blog.

- Joh, T. H., and O. Hwang. 1987. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase: Biochemistry and molecular biology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 493: 342-50. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- Longe, J. L. 2006. The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414403682.

- Krapp, Kristine M., and Jeffrey Wilson. 2005. The Gale encyclopedia of children's health: infancy through adolescence. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 0787692417.

- Michals, K., and R. Matalon. 1985. Phenylalanine metabolites, attention span and hyperactivity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 42(2): 361-365. PMID 4025205.

- Pietz, J., R. Kreis, A. Rupp, E. Mayatepek, D. Rating, C. Boesch, and H. J. Bremer. 1999. Large neutral amino acids block phenylalanine transport into brain tissue in patients with phenylketonuria. Journal of Clinical Investigation 103: 1169–1178. PMID 10207169.

External links

- Phenylketonuria Description and diagram

- Genetics of Phenylketonuria

- National PKU News

- European Society for PKU and allied Disorders

- Recent primary literature on phenylketonuria

- International PKU Discussion Board Articles, Events, Recipes, etc.

- British National Society for Phenylketonuria

- PKU Exchange Diet management, tools, forum and information for PKU patients

- PKUWiki A wiki focused on PKU

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Folling, A. (1934). Ueber Ausscheidung von Phenylbrenztraubensaeure in den Harn als Stoffwechselanomalie in Verbindung mit Imbezillitaet. Ztschr. Physiol. Chem. 227: 169-176.

- ↑ Centerwall, S. A. & Centerwall, W. R. (2000). The discovery of phenylketonuria: the story of a young couple, two retarded children, and a scientist.. Pediatrics 105 (1 Pt 1): 89-103. PMID 10617710.