Pardon

|

| Criminal procedure |

|---|

| Criminal investigation |

| Arrest · Warrant |

| Criminal prosecution |

| Bail |

| Evidence (law) · Extradition |

| Grand jury · Habeas corpus |

| Indictment · Plea bargain |

| Statute of limitations |

| Trial |

| Double jeopardy · Jury |

| Rights of the accused |

| Self-incrimination |

| Sentence (law) |

| Post-sentencing |

| Pardon |

| Parole |

| Probation |

An authorized official can pardon, or forgive, a crime and its penalty; or grant clemency, or the lessening of the punishment, by means of a reprieve. The procedures for granting pardons vary according to each nation's legal system, as do the effects of the pardon. In particular, the issue of whether a pardon clears the individual from all wrong-doing, as if they were innocent, or whether it merely removes the punishment in an act of forgiving their offense.

Public debate invariable surrounds the pardoning of a criminal, despite teachings in all world religions that stress the importance of forgiveness. Activists contend that the act of pardoning or granting clemency means little without rehabilitation, reconciliation, or recompense on the part of the forgiven. For others, the act of pardoning is noble and reflects the quality of divine forgiveness and grace to which rulers should aspire and through which human society can become more ideal. Ultimately, though, the issue of pardoning those who commit serious crimes against society is one that cannot be resolved to the satisfaction of all. The only way for all to be satisfied is for such crimes not to be committed.

Definitions

Pardon and related terms differ subtly from country-to-country. Generally, however, the follow definitions hold.[1][2]

- Amnesty

Amnesty is an act of justice by which the supreme power in a state restores those who may have been guilty of any offense against it to the position of innocent persons. It includes more than a pardon, inasmuch as it obliterates all legal remembrance of the offense. Thus it can be seen as "forgetting" a crime. For example, if a car thief witnesses a murder, he may be granted amnesty for his crime in order to allow him to testify against the murderer; or after a civil war a mass amnesty may be granted to absolve all participants of guilt. Weapon amnesties may be granted so that people can turn in illegal weapons to the police without any legal consequences.

- Commutation

Commutation of sentence involves the reduction of legal penalties, especially in terms of imprisonment. Unlike a pardon, a commutation does not nullify the conviction and is often conditional. It commonly involves substituting the penalty for one crime with the penalty for another, whilst still remaining guilty of the original crime. Thus, in the United States, someone who is guilty of murder may have their sentence commuted to life imprisonment rather than death.

- Pardon

A pardon is the forgiveness of a crime and the penalty associated with it. It is granted by a sovereign power, such as a monarch, chief of state, or a competent church authority.

- Remission

In this case there is complete or partial cancellation of the penalty for a crime, whilst still being considered guilty of the crime. Thus it may results in a reduced penalty.

- Reprieve

This is temporary postponement of a punishment, usually so that the accused can mount an appeal. A reprieve may be extended to a prisoner, providing a temporary delay in imposition of the death penalty, pending the outcome of their appeal, to allow an opportunity to obtain a reduction in sentence. A reprieve is only a delay and is not a reduction of sentence, commutation of sentence, or pardon.[3]

- Clemency

A catch-all term for all of the above, which may also refer specifically to amnesties and pardons. Clemency is often requested by foreign governments that do not practice capital punishment when one of their citizens has been sentenced to death by a foreign nation. It means the lessening of the penalty of the crime without forgiving the crime itself.

History

Nations around the world have their own unique rules, laws, and procedures for granting pardons and reprieves, with differences stemming from varying histories, cultural make-up, and religious traditions.

Divine Right of Kings

In Western culture, pardons and clemency resulted from rulers claiming the “divine right” to rule. Roman emperors (such as Nero, Caligula, and Julius Caesar), who exercised the absolute right of life and death over their subjects, were replaced in Europe by hereditary royalty. During the Middle Ages, monarchs governed under the notion of the “Divine Right,” with their subjects meant to believe that God personally authorized the right of their kings to rule. The medieval Roman Catholic Church utilized the act of pardoning for the remission of punishment for an offense, specifically as a papal indulgence.

With such divine power, such "perfect" monarchs had the absolute right to decide who was, and was not, to be arrested, tried, convicted, tortured, or executed. At times, a king could publicly demonstrate his benevolence by pardoning individuals.

The notion of the Divine Right of Kings began to break down with the first English Civil War. The national conflict had the English middle class fighting against the monarch, William I, and his supporters. While the army proposed an undoing of the Divine Right of Kings and a new government based on representative democracy fostering equal rights for the people, Cromwell prevailed.

Although the American Revolutionary War was inspired in part by the stance previously taken by the Levelers, a leftover from the British period of Divine Right was retained by the American Forefathers—the absolute right to pardon criminals of all sorts. Therefore, even today an American political leader can evoke executive privilege—like the Roman emperors once did—and exercise the right to pardon someone without having to justify their action.

Religious basis

The act of pardoning (or forgiving) someone has religious origins. In Luke's account of the crucifixion of Jesus, Jesus says from the cross: "Father, forgive them for they do not know what they are doing." In speaking such, he requested a pardon for those responsible in his death. Christianity teaches there are two aspects to forgiveness. The wrongdoer only has to accept Jesus as his personal savior and since He is all-forgiving, then the matter is closed. Meanwhile, the transgressed must search his heart and despite his suffering, must let go of any negative feelings towards the wrongdoer.

Judaism teaches that the wrongdoer must accept full responsibility for offending others, while admitting to him or herself that they have committed a sin without trying to justify the misdeed. The wrongdoer is responsible and therefore must try to make amends.

Buddhism is a philosophy that teaches how one should live a moral and ethical life. Forgiveness is not something that can be commanded, but rather it is accomplished by surrendering negative emotions like hate and the urge for revenge to attain a higher level of consciousness. Forgiveness can occur when negative emotions have abated toward those who would harm others.

In Islam, forgiveness is the sole domain of Allah, who is known as Beneficent, Merciful, and Forgiving. In order for forgiveness to occur, the misdeed must be the result of ignorance, not the wrongdoer expecting that Allah will forgive him for his misdeed. The wrongdoer must quickly feel authentic shame and remorse about what their misdeed, and after requesting forgiveness, they must solemnly pledge to change their ways. Deathbed redemptions do not exist in Islam, since a person who has lived an evil life cannot be forgiven at the last moment. In Islamic countries, Sharia law, based upon interpretations of the Qur'an, is used to determine the relevance of pardons.[4] [5].

The concept of having performing atonement from one's wrongdoing (Prayaschitta—Sanskrit: Penance), and asking for forgiveness is very much a part of the practice of Hinduism. Prayashitta is related to the law of Karma. Karma is a sum of all that an individual has done, is currently doing and will do. The effects of those deeds and these deeds actively create present and future experiences, thus making one responsible for one's own life, and the pain in others.

Forgiveness is espoused by Krishna, who is considered to be an incarnation (avatar) of Vishnu by Hindus. Krishna said in the Bhagavad Gita (Chapter 16, verse 3) that forgiveness is one of the characteristics of one born for a divine state. He distinguished those good traits from those he considered to be demonic, such as pride, self-conceit, and anger.

In pantheistic cultures, a person who harmed another must remedy the misdeed whether it was intentional or accidental. Survival is key, not forgiveness. Therefore, even if a person is killed, then the relatives who bore the burden of the death must receive assistance from the wrongdoer. Yet if the wrongdoer did not change his ways or represented a continued threat to the community, then he could be shunned or exiled even by his blood relatives. The wrongdoer would then be entitled to no forgiveness or redemption, and probably die on his own.

World situation

Today, pardons and reprieves are granted in many countries when individuals have demonstrated that they have fulfilled their debt to society, or are otherwise deserving (in the opinion of the pardoning official) of a pardon or reprieve. Pardons are sometimes offered to persons who claim they have been wrongfully convicted. Some believe accepting such a pardon implicitly constitutes an admission of guilt, with the result that in some cases the offer is refused (cases of wrongful conviction are more often dealt with by appeal than by pardon).

Nations around the world have a variety of rules and procedures for granting pardons and reprieves. Much of these differences stem from each nation's cultural and political concepts of forgiveness. Pardons exist in totalitarian and communist nations, but they are given out at the whim of the leaders rather than based in any clear value system.

North America

United States

In the United States, the pardon power for Federal crimes is granted to the President by the United States Constitution, Article II, Section 2, which states that the President:

shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.

The Supreme Court has interpreted this language to include the power to grant pardons, conditional pardons, commutations of sentence, conditional commutations of sentence, and remissions of fines and forfeitures, respites and amnesties.[6] All federal pardon petitions are addressed to the President, who grants or denies the request. Typically, applications for pardons are referred for review and non-binding recommendation by the Office of the Pardon Attorney, an official of the Department of Justice. The percentage of pardons and reprieves granted varies from administration to administration.[7]

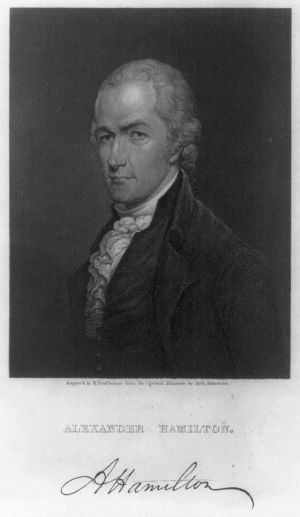

The pardon power was controversial from the outset; many Anti-Federalists remembered examples of royal abuses of the pardon power in Europe, and warned that the same would happen in the new republic. However, Alexander Hamilton defends the pardon power in The Federalist Papers, particularly in Federalist No. 74. In his final day in office, George Washington granted the first high-profile Federal pardon to leaders of the Whiskey Rebellion.

Many pardons have been controversial; critics argue that pardons have been used more often for the sake of political expediency than to correct judicial error. One of the more famous such pardons was granted by President Gerald Ford to former President Richard Nixon on September 8, 1974, for official misconduct which gave rise to the Watergate scandal. Polls showed a majority of Americans disapproved of the pardon, and Ford's public-approval ratings tumbled afterward. Other controversial uses of the pardon power include Andrew Johnson's sweeping pardons of thousands of former Confederate officials and military personnel after the American Civil War, Jimmy Carter's grant of amnesty to Vietnam-era draft evaders, George H. W. Bush's pardons of 75 people, including six Reagan administration officials accused and/or convicted in connection with the Iran-Contra affair, Bill Clinton's pardons of convicted Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (Puerto Rico) (FALN) terrorists and 140 people on his last day in office—including billionaire fugitive Marc Rich, and George W. Bush's commutation of I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby's prison term.

The Justice Department recommends anyone requesting a pardon must wait five years after conviction or release prior to receiving a pardon. A presidential pardon may be granted at any time, however, and as when Ford pardoned Nixon, the pardoned person need not yet have been convicted or even formally charged with a crime. Clemency may also be granted without the filing of a formal request and even if the intended recipient has no desire to be pardoned. In the overwhelming majority of cases, however, the Pardon Attorney will consider only petitions from persons who have completed their sentences and, in addition, have demonstrated their ability to lead a responsible and productive life for a significant period after conviction or release from confinement.[8]

A pardon may be rejected, and must be affirmatively accepted to be officially recognized by the courts. Acceptance carries with it an admission of guilt.[9] However, the federal courts have yet to make it clear how this logic applies to persons who are deceased (such as Henry O. Flipper—who was pardoned by Bill Clinton), those who are relieved from penalties as a result of general amnesties, and those whose punishments are relieved via a commutation of sentence (which cannot be rejected in any sense of the language).[10]

The pardon power of the President extends only to offenses cognizable under United States Federal law. However, the governors of most states have the power to grant pardons or reprieves for offenses under state criminal law. In other states, that power is committed to an appointed agency or board, or to a board and the governor in some hybrid arrangement.

Canada

In Canada, pardons are considered by the National Parole Board under the Criminal Records Act, the Criminal Code, and several other laws. For Criminal Code crimes there is a three-year waiting period for summary offences, and a five-year waiting period for indictable offences. The waiting period commences after the sentence is completed. Once pardoned, a criminal records search for that individual reveals "no record."

In Canada, clemency is granted by the Governor-General of Canada or the Governor in Council (the federal cabinet) under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy. Applications are also made to the National Parole Board, as in pardons, but clemency may involve the commutation of a sentence, or the remission of all or part of the sentence, a respite from the sentence (for a medical condition), or a relief from a prohibition (such as to allow someone to drive who had been prohibited from driving).

Europe

France

Pardons and acts of clemency (grâces) are granted by the President of France, who, ultimately, is the sole judge of the propriety of the measure. It is a prerogative of the President which is directly inherited from that of the Kings of France. The convicted person sends a request for pardon to the President of the Republic. The prosecutor of the court that pronounced the verdict reports on the case, and the case goes to the Ministry of Justice's directorate of criminal affairs and pardons for further consideration. If granted, the decree of pardon is signed by the President, the Prime Minister, the Minister of Justice, and possibly other ministers involved in the consideration of the case.

The decree may spare the applicant from serving the balance of his or her sentence, or commute the sentence to a lesser one. It does not suppress the right for the victim of the crime to obtain compensation for the damages suffered, and does not erase the condemnation from the criminal record.

When the death penalty was in force in France, almost all capital sentences resulted in a presidential review for possible clemency. Sentenced criminals were routinely given a sufficient delay before execution so that their requests for clemency could be examined. If granted, clemency usually entailed a commutation to a life sentence.

Germany

Similar to the United States, the right to grant pardons in Germany is divided between the federal and the state level. Federal jurisdiction in matters of criminal law is mostly restricted to appeals against decisions of state courts. Only "political" crimes like treason or terrorism are tried on behalf the federal government by the highest state courts. Accordingly, the category of persons eligible for a federal pardon is rather narrow. The right to grant a federal pardon lies in the office of the President, but he or she can transfer this power to other persons, such as the chancellor or the minister of justice.

For all other (and therefore the vast majority of) convicts, pardons are in the jurisdiction of the states. In some states it is granted by the respective cabinet, but in most states the state constitution vests the authority in the state prime minister. As on the federal level, the authority may be transferred. Amnesty can be granted only by federal law.

Greece

The Constitution of Greece grants the power of pardon to the President of the Republic (Art. 47, § 1). He can pardon, commute, or remit punishment imposed by any court, on the proposal of the Minister of Justice and after receiving the opinion (not the consent necessarily) of the Pardon Committee.

Ireland

Under the Constitution of Ireland Art 13 Sec 6, the President can pardon convicted criminals: "The right of pardon and the power to commute or remit punishment imposed by any court exercising criminal jurisdiction are hereby vested in the President, but such power of commutation or remission may also be conferred by law on other authorities."

Italy

In Italy, the President Republic may “grant pardons, or commute punishments” according to article 87 of the Italian Constitution. Like other acts of the president, the pardon requires the countersignature of the competent government minister. The Constitutional Court of Italy has ruled that the Minister of Justice is obliged to sign acts of pardon.[11] The pardon may remove the punishment altogether or change its form. Unless the decree of pardon states otherwise, the pardon does not remove any incidental effects of a criminal conviction, such as a mention in a certificate of conduct (174 c.p.).

According to article 79 of the Italian Constitution, a two-thirds majority vote by Parliament may grant amnesty (article 151 c.p.) and pardons (article 174 c.p.).

Poland

In Poland, the President is granted the right of pardon by Article 133 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland. As of October 2008, 7,819 people have been pardoned, while 3,046 appeals were declined.

- Lech Wałęsa

- approved - 3,454

- declined - 384

- Aleksander Kwaśniewski

- approved - 3,295 (the first term); 795 (the second term); total - 4,090

- declined - 993 (the first term); 1,317 (the second term); total - 2,310

- Lech Kaczyński (until October 2007)

- approved - 77

- declined - 550

Russia

The President of the Russian Federation is granted the right of pardon by Article 89 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation. The Pardon Committee manages lists of people eligible for pardon and directs them to the President for signing. While President Boris Yeltsin frequently used his power of pardon, his successor Vladimir Putin was much more hesitant; in the final years of his presidency he did not grant pardons at all.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, pardons may be granted by the Swiss Federal Assembly for crimes prosecuted by the federal authorities. For crimes under cantonal jurisdiction, cantonal law designates the authority competent to grant pardons (if any). In most cantons, the cantonal parliament may pardon felonies, and the cantonal government may pardon misdemeanors and minor infractions.

United Kingdom

The power to grant pardons and reprieves is a royal prerogative of mercy of the monarch of the United Kingdom. It was traditionally in the absolute power of the monarch to pardon and release an individual who had been convicted of a crime from that conviction and its intended penalty. Pardons were granted to many in the eighteenth century on condition that the convicted felons accept transportation overseas, such as to Australia. The first General Pardon in England was issued in celebration of the coronation of Edward III in 1327. In 2006, all British soldiers executed for cowardice during World War I were pardoned, resolving a long-running controversy about the justice of their executions.[12]

Today, however, the monarch may only grant a pardon on the advice of the Home Secretary or the First Minister of Scotland (or the Defense Secretary in military justice cases), and the policy of the Home Office and Scottish Executive is only to grant pardons to those who are "morally" innocent of the offense (as opposed to those who may have been wrongly convicted by misapplication of the law). Pardons are generally no longer issued prior to conviction, but only after conviction. A pardon is no longer considered to remove the conviction itself, but only removes the penalty which was imposed. Use of the prerogative is now rare, particularly since the establishment of the Criminal Cases Review Commission and Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission, which provide a statutory remedy for miscarriages of justice.

According to the Act of Settlement, a pardon cannot prevent a person from being impeached by Parliament, but may rescind the penalty following conviction. In England and Wales, nobody may be pardoned for an offense under section 11 of the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 (unlawfully transporting prisoners out of England and Wales).[13]

Other

Hong Kong

Prior to the transfer of the sovereignty of Hong Kong to China in 1997, the power of pardon was a royal prerogative of mercy of the monarch of the United Kingdom. This was used and cited the most often in cases of inmates who had been given the death penalty: from 1965 to 1993 (when the death penalty was formally abolished) those who were sentenced to death were automatically commuted to life imprisonment under the Royal Prerogative.

Since the handover, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong exercises the power to grant pardons and commute penalties under section 12 of article 48 Basic Law of Hong Kong: "The Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall exercise the following powers and functions... To pardon persons convicted of criminal offences or commute their penalties."

India

Under the Constitution of India (Article 72), the President can grant a pardon or reduce the sentence of a convicted person, particularly in cases involving capital punishment. A similar and parallel power vests in the Governors of each State under Article 161.

However, it is important to note that India has a unitary structure of government and there is no body of state law. All crimes are crimes against the Union of India. Therefore, a convention has developed that the Governor's powers are exercised only for minor offenses, while requests for pardons and reprieves for major offenses and offenses committed in the Union Territories are deferred to the President.

Iran

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Supreme Leader has the power to pardon and offer clemency under the Constitution, Article 110, § 1, §§ 11.

Israel

In Israel the President has the power to pardon criminals or give them clemency. The pardon is given following a recommendation by the Minister of Justice.

After the Kav 300 affair, resulting from the 1984 hijacking of an Israeli bus by Palestinian gunmen and the allegations that two of the gunmen were subsequently executed by General Security Service (Shin Bet) agents while being held captive, President Chaim Herzog issued a pardon to four members of the Shin Bet prior to their indictment. This unusual act was the first of its kind in Israel.

South Africa

Under section 84(2)(j) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Act 108 of 1996), the President of the Republic of South Africa is responsible for pardoning or reprieving offenders. This power of the president is only exercised in highly exceptional cases.

Pardon is only granted for minor offenses after a period of ten years has elapsed since the relevant conviction. For many serious offenses (for example if the relevant court viewed the offense in such a serious light that direct imprisonment was imposed), pardon will not be granted even if more than ten years have elapsed since the conviction.

Social issues

The notion of forgiveness is generally considered a private matter between individuals, and in some cultures has been thought of as an action taken by weak people, meaning those who do not have the ability to take revenge. Indeed, a person who forgives another might even be seen as a coward. Forgiveness is often viewed as unrelated to greater social issues or those social concerns that impact the lives of many people. However, when forgiveness is practiced by a public official in the form of a pardon or reprieve, then social concerns invariably come into play.

A key social component of forgiveness is that to forgive—or granting a pardon or reprieve—does not offset the need for punishment and recompense. However, the notion of forgiveness is intimately connected to the ideas of repentance and reconciliation. In the American legal system, among others, society has stressed the rehabilitation of the wrong doer, even after pardoning or recompense occurs. Although it is important to uphold the rule of law, and to prevent the miscarriage of justice, society also seeks to avoid the rush to judgment.

Another publicly debated consideration is whether pardoning someone or granting a reprieve can change the behavior of the forgiven individual. There is no proven cause-effect relationship between the act of pardoning and future criminal behavior or lack thereof. Social activists have argued that rehabilitation and reconciliation is the best solution for discouraging future criminal behavior. For others, though, the act of pardoning the wrong doer is more effective than punishment.

There is also the issue that the power to pardon is susceptible to abuse if applied inconsistently, selectively, arbitrarily, or without strict, publicly accessible guidelines. The principle of the Rule of Law is intended to be a safeguard against such arbitrary governance. In its most basic form, this is the principle that no one is above the law. As Thomas Paine stated in his pamphlet Common Sense (1776), "For as in absolute governments the king is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other." Thus, while forgiveness and mercy may be seen as desirable traits in a healthy society, these should not supercede a valid and properly working legal system but rather should be embodied within it.

Notable pardons

- In 1794, George Washington pardoned the leaders of the Whiskey Rebellion, a Pennsylvania protest against federal taxes on "spirits."

- In 1799, John Adams pardoned participants in the Fries Uprising, a Pennsylvania protest against federal property taxes.

- In 1869, Andrew Johnson pardoned Samuel Mudd, a doctor who treated the broken leg of Abraham Lincoln's assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

- In 1971, Richard Nixon commuted the sentence of labor union leader Jimmy Hoffa, who had been convicted of jury tampering and fraud.

- In 1974, Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon, preempting any conviction of Watergate-related crimes. In a televised broadcast to the nation, Ford explained that he felt the pardon was in the best interests of the country and that the Nixon family's situation "is an American tragedy in which we all have played a part. It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must."[14]

- In 1977, Ford pardoned "Tokyo Rose" (Iva Toguri), an American forced to broadcast propaganda to Allied troops in Japan during World War II.

- In 1979, Jimmy Carter commuted Patricia Hearst's armed-robbery sentence. She was pardoned by Bill Clinton in 2001.

- In 1989, Ronald Reagan pardoned New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner for making illegal contributions to Nixon's re-election campaign in 1972.

- In 1992, George H.W. Bush pardoned six defendants in the Iran-contra investigation, including former Defense Decretary Caspar Weinberger and former national security adviser Robert McFarlane.

- In 2001, Clinton pardoned fugitive billionaire Marc Rich, his half-brother Roger Clinton, and Susan McDougal, who went to jail for refusing to answer questions about Clinton's Whitewater dealings.

- In 2002, 11 rebel ethnic Albanian fighters have been granted pardons by the Macedonian President Boris Trajkovski. The amnesty was part of a Western-backed peace plan, meant to end an insurgency by ethnic Albanian guerrillas.

- In 2007, five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor were pardoned by Bulgarian President Georgi Parvanov on arrival in Sofia, after spending eight-and-a-half years in prison in Libya. The medics were sentenced to life in prison in Libya for contaminating children with the AIDS virus.

- in 2008, Chadian President Idriss Deby pardoned six French nationals found guilty in 2007 of abducting more than 100 children from eastern Chad in what they called a humanitarian mission.

- In 2008, the Swiss government pardoned Anna Goeldi 226 years after she was beheaded for being a witch. Goeldi was the last person in Europe to be executed for witchcraft.

Notes

- ↑ Amnesty and Pardon - Terminology And Etymology Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Amnesty and Pardon - Clemency Powers In The Twentieth Century Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Gerald N. Hill and Kathleen T. Hill, Reprieve, Farlex Inc., 2005. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ George Conger, Appeal for Saudi woman facing death penalty for 'witchcraft,' Religious Intelligence. February 15, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Walter Jayawardhana, Lawyer representation not required under Shariah law for minor condemned to die, says Saudi daily, Asian Tribune, 2007-07-19. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ P. S. Ruckman, Jr., “Executive Clemency in the United States: Origins, Development, and Analysis (1900-1993),” Presidential Studies Quarterly 27 (1997): 251-271.

- ↑ P. S. Ruckman, Jr., Presidential Pardons by Administration, 1789-2001, Pardon Me, Mr. President.

- ↑ United States Department of Justice, Clemency Regulations Rules Governing Petitions for Executive Clemency, United States Department of Justice. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Burdick v. United States, 236 U.S. 79 (1915)

- ↑ Chapman v. Scott (C. C. A.) 10 F.(2d) 690)

- ↑ Pardons in Italy TripAtlas.com. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- ↑ Ben Fenton, Pardoned: the 306 soldiers shot at dawn for 'cowardice,' Telegraph.co.uk, 16 Aug 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ The UK Statute Law Database, Habeas Corpus Act 1679 (c. 2). Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Gerald R. Ford Gerald R. Ford Pardoning Richard Nixon Great Speeches Collection, The History Place, September 8, 1974. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Crouch, Jeffrey P. The Presidential Pardon Power. Ph.D. dissertation. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America, 2008. OCLC 263428239

- Dershowitz, Alan M. What's Mercy Got To Do With It? New York Times, July 16, 1989. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- Dressler, Joshua. Encyclopedia of Crime and Justice. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference, 2002. ISBN 978-0028653198

- National Government Publication. Justice Undone: Clemency Decisions in the Clinton White House: Second Report by the United States Congress, House Committee on Government Reform. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2002. OCLC 49871132

- Sarat, Austion, and Hussain, Nasser. Forgiveness, Mercy, and Clemency. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0804753326

- Sirica, John J. To Set the Record Straight: The Break-in, the Tapes, the Conspirators, the Pardon. New York, NY: Norton, 1979. ISBN 978-0393012347

External links

All links retrieved March 24, 2015.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.