Difference between revisions of "Papacy" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

In the second century, Roman bishops received visits and letters from other churches indicating that Rome held a position of unique respect. By the second half of the century, it is probably that the tradition of collective leadership at Rome had given way to a single ruling bishop, as was the case in several other major cities. Because of the relative wealth of the Roman church, the early popes helped spread Christianity abroad. They were also instrumental in resolving doctrinal disputes, both because of Rome's position as capital of the empire and on the basis of Rome's connection with [[Saint Peter]]. [[Irenaeus of Lyons]]'s ''[[On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis|Against Heresies]]'' (3:3:2) stated: "With [the Church of Rome], because of its superior origin, all the churches must agree... and it is in her that the faithful everywhere have maintained the apostolic tradition." However, in 195, when [[Pope Victor I]] excommunicated several Eastern churches for observing [[Easter]] on the Jewish [[Passover]], Irenaeus himself disagreed with this action, which was later rescinded. Marcellinus (d. 304) is the first bishop of Rome whom sources show used the title of "pope." | In the second century, Roman bishops received visits and letters from other churches indicating that Rome held a position of unique respect. By the second half of the century, it is probably that the tradition of collective leadership at Rome had given way to a single ruling bishop, as was the case in several other major cities. Because of the relative wealth of the Roman church, the early popes helped spread Christianity abroad. They were also instrumental in resolving doctrinal disputes, both because of Rome's position as capital of the empire and on the basis of Rome's connection with [[Saint Peter]]. [[Irenaeus of Lyons]]'s ''[[On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis|Against Heresies]]'' (3:3:2) stated: "With [the Church of Rome], because of its superior origin, all the churches must agree... and it is in her that the faithful everywhere have maintained the apostolic tradition." However, in 195, when [[Pope Victor I]] excommunicated several Eastern churches for observing [[Easter]] on the Jewish [[Passover]], Irenaeus himself disagreed with this action, which was later rescinded. Marcellinus (d. 304) is the first bishop of Rome whom sources show used the title of "pope." | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Attila-PopeLeo-ChroniconPictum.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Pope Leo I]] meets with [[Attila the Hun]].]] | ||

When Emperor [[Constantine I]] legalized Christianity and showed special favor to the Christian churches, Rome's position was initially bolstered, and the office of the papacy became a political and financial prized of great power. Though the progressive [[Christianization]] of the [[Roman Empire]] in the fourth century did not confer upon bishops any direct civil authority within the state, the gradual withdrawal of imperial authority during the fifth century left the pope in the ''de facto'' position the senior imperial civilian official in Rome. | When Emperor [[Constantine I]] legalized Christianity and showed special favor to the Christian churches, Rome's position was initially bolstered, and the office of the papacy became a political and financial prized of great power. Though the progressive [[Christianization]] of the [[Roman Empire]] in the fourth century did not confer upon bishops any direct civil authority within the state, the gradual withdrawal of imperial authority during the fifth century left the pope in the ''de facto'' position the senior imperial civilian official in Rome. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Meanwhile, when Constantine established his hew capital at [[Byzantium]] under the new name of [[Constantinople]], this effectively split the church into a Greek East and a Latin West. The popes, with some notable exceptions, grew increasingly independent of the emperor and became a major force in politics in the West. Meanwhile, the See of Constantinople emerged as a second center of ecclesiastical authority in the East, often at odds with Rome over questions of jurisdiction, honor, authority, and even theology. | Meanwhile, when Constantine established his hew capital at [[Byzantium]] under the new name of [[Constantinople]], this effectively split the church into a Greek East and a Latin West. The popes, with some notable exceptions, grew increasingly independent of the emperor and became a major force in politics in the West. Meanwhile, the See of Constantinople emerged as a second center of ecclesiastical authority in the East, often at odds with Rome over questions of jurisdiction, honor, authority, and even theology. | ||

Revision as of 19:21, 3 January 2009

| Pope | |

| Catholicism | |

Seal of the Papacy | |

| |

| Incumbent: Benedict XVI | |

| Styles | His Holiness |

|---|---|

| Holy Father | |

| Residence | Vatican City |

| First Pope | Traditionally, Saint Peter |

| Formation | Traditionally, first century |

| Website | www.vatican.va |

The papacy is the office of the pope (from Latin: "papa" or "father" from Greek πάπας, pápas), the bishop of Rome, who is the leader of the Roman Catholic Churchand head of state of Vatican City. The pope's ecclesiastical jurisdiction is called the "Holy See" or "Apostolic See."

The early bishops of Rome were not yet "popes" as the word is understood today. Rather, the Roman church seems to have had a collective leadership involving a council of elders or bishops until the mid-second century. The Christian community at Rome gained prominence gradually, especially after the scattering of the Jerusalem church in 70 C.E., and eventually became the leading church in the Roman Empire. After Christianity become the religion of the emperors in the fourth century, the papacy was involved a period of close interaction with the rulers of the West, while often struggling for supremacy with the eastern emperors and the patriarch of Constantinople. In medieval times, popes played powerful political roles in Western Europe, crowning emperors, ruling the papal states, and regulating disputes among secular rulers.

Eastern Orthodoxy has never accepted the jurisdiction of Rome, and Protestant Reformation successfully challenged the papacy in the West. The popes were gradually forced to give up secular power, and in recent decades, the papacy has come to focus again almost exclusively on spiritual matters. Over the centuries, the papacy's claim of spiritual authority has been ever more clearly expressed, culminating in the proclamation of the dogma of papal infallibility for those rare occasions the pope speaks ex cathedra (literally "from the chair (of Peter)") when issuing a solemn definition of faith or morals.

History

Earliest church

The importance of the Roman bishop is largely derived from his role as the successor to Saint Peter, to whom Jesus gays the keys of heaven and powering of "binding and loosing" on earth and in heaven, naming him as the "rock" upon which the church would be built.

In the earliest Christian era, however, it was Jerusalem, not Rome, that served as Christianity's the central Christian community, from which missionary were sent and to which delegates came to resolve disputes. James the Just, known as "the brother of the Lord", served as head of the Jerusalem church, which is still honored as the "Mother Church" in Orthodox tradition. Antioch and Alexandria also had important congregations. Rome, the capital of the Roman empire, was one of the first Gentile cities to develop a large congregation early in the apostolic period, and it was at Rome that the Apostle Paul was martyred, soon followed by Peter, according to tradition.

During the first century of the Christian Church (ca. 30-130 C.E.), there are few if any reference to Rome's primacy among the churches, and even the idea of Peter's acting as bishop of Rome is heavily disputed. However, after the Jerusalem church was disbanded in the wake of the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 C.E., Rome gradually came to the fore. For example in the last years of the first century, Clement of Rome, probably one of a council of bishops traditionally recognized as the second pope, wrote to the church Corinth to intervene in an internal dispute there.

The papacy emerges

In the second century, Roman bishops received visits and letters from other churches indicating that Rome held a position of unique respect. By the second half of the century, it is probably that the tradition of collective leadership at Rome had given way to a single ruling bishop, as was the case in several other major cities. Because of the relative wealth of the Roman church, the early popes helped spread Christianity abroad. They were also instrumental in resolving doctrinal disputes, both because of Rome's position as capital of the empire and on the basis of Rome's connection with Saint Peter. Irenaeus of Lyons's Against Heresies (3:3:2) stated: "With [the Church of Rome], because of its superior origin, all the churches must agree... and it is in her that the faithful everywhere have maintained the apostolic tradition." However, in 195, when Pope Victor I excommunicated several Eastern churches for observing Easter on the Jewish Passover, Irenaeus himself disagreed with this action, which was later rescinded. Marcellinus (d. 304) is the first bishop of Rome whom sources show used the title of "pope."

When Emperor Constantine I legalized Christianity and showed special favor to the Christian churches, Rome's position was initially bolstered, and the office of the papacy became a political and financial prized of great power. Though the progressive Christianization of the Roman Empire in the fourth century did not confer upon bishops any direct civil authority within the state, the gradual withdrawal of imperial authority during the fifth century left the pope in the de facto position the senior imperial civilian official in Rome.

Meanwhile, when Constantine established his hew capital at Byzantium under the new name of Constantinople, this effectively split the church into a Greek East and a Latin West. The popes, with some notable exceptions, grew increasingly independent of the emperor and became a major force in politics in the West. Meanwhile, the See of Constantinople emerged as a second center of ecclesiastical authority in the East, often at odds with Rome over questions of jurisdiction, honor, authority, and even theology.

At the ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451 Pope Leo I (through his emissaries) stated that he was "speaking with the voice of Peter". At this same council, the patriarch of Constantinople was given a primacy of honor equal to that of the bishop of Rome, and Constantnople was declared the "New Rome." In practice, however, Rome and Constantinople continued to struggle for supremacy, and several schisms followed. During this period there five metropolitan archbishops held the title of "patriarch": Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. The term "pope" was used from the early third century as an honorific designation used for any bishop in the West. In the East it was used only for the bishop of Alexandria. From the early sixth century it began to be confined in the West to the bishop of Rome, a practice that was firmly in place by the eleventh century. However, the Alexandrian churches, both Coptic and Orthodox, still refer to their bishops as popes.

Medieval development

After the fall of Rome to the "barbarians," the Roman served as a source of knowledge, authority, and continuity in the West. Gregory the Great (c 540-604) administered the church with wisdom and stern reform. However, Gregory's successors were sometimes dominated by the exarch or the Eastern emperor. Pope Stephen II, seeking protection from the Lombards appealed to the Franks to protect papal territory. In 754, Pepin the Short subdued the Lombards, giving the pope the conquered lands, which formed the core of the Papal States. In 800 C.E., Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman emperor, establishing the precedent in the Wewst that no man would be emperor without anointment by a pope. The East, however, continued its imperial tradition without papal authority, upon which it had never depended.

Around 850, a collection of church legislation was promulgated that contained forgeries as well as genuine documents, known today as the False Decretals. Its principal aim was to free the church and its bishops from interference by the state and the metropolitans respectively. The author, a French cleric calling himself Isidore Mercator, presented various documents purportedly by early church popes, demonstrating that supremacy of the papacy dated back to the church's oldest traditions. The decretals include the Donation of Constantine, in which Constantine grants Pope Sylvester I secular authority over all Western Europe. the "Pseudo-Isidorian" decretals supported papal authority for centuries.

During the last two centuries of the first millennium, the papacy came under the control of vying political factions, and the papacy's prestige was badly tarnished. Conflict between the emperor and the papacy continued, and eventually dukes in league with the emperor were buying bishops and popes almost openly. In 1049, Leo IX became pope and attempted serious reforms. He traveled to the major cities of Europe to deal with the church's moral problems firsthand, notably the sale of church offices or services and clerical marriage and concubinage.

Christianity of the East and West split definitively in 1054. This "Great Schism" was caused more by political events than by diversities of creed, although the famous filioque clause inserted into the Nicene Creed by the popes played no small role in it.

From 1309 to 1377, the pope resided not in Rome but in Avignon. The Avignon Papacy was notorious for greed and corruption. During this period, the pope was effectively an ally of France, alienating France's enemies, such as England.

The pope was understood to have the power to draw on the "treasury" of merit built up by the saints and by Christ, so that he could grant indulgences, reducing one's time in purgatory. The concept that a monetary fine or donation accompanied contrition, confession, and prayer eventually gave way to the common understanding that indulgences depended on a simple monetary contribution. Popes condemned misunderstandings and abuses of the practice, but were too pressed for income to exercise effective control over indulgences.

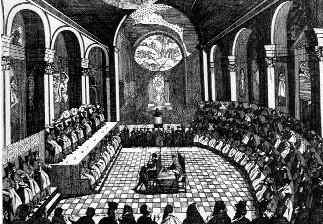

Popes also contended with the cardinals, who sometimes attempted to assert the authority of councils over the pope's. Conciliar theory holds that the supreme authority of the church lies with a General Council, not with the pope. The failure of the conciliar theory to win general acceptance after the 15th century is taken as a factor in the Protestant Reformation.

Various antipopes also challenged papal authority, especially during the Western Schism (1378 - 1417). During this schism one pope reigned in Avignon while another (or even two) popes reigned in Rome.

Reformation to present (1517 to today)

Protestant Reformation criticized the papacy as corrupt and challenged to idea of papal authority both administratively and theologically.

Popes instituted the Counter Reformation(1560 - 1648) to address this challenge and institute internal reforms. Pope Paul III (1534-1549) initiated the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which succeeded in the papacy's retaining control over southern Europe. Gradually however, the papacy was forced to give up secular power, focusing increasingly on spiritual issues.

In 1870, the First Vatican Council proclaimed the dogma of papal infallibility for those rare occasions the pope speaks ex cathedra (literally "from the chair (of Peter)") when issuing a solemn definition of faith or morals. Later in 1870, Victor Emmanuel II seized Rome from the pope's control and substantially completed the unification of Italy. In 1929, the Lateran Treaty between Italy and Pope Pius XI established the Vatican guaranteed papal independence from secular rule.

In 1950, the pope defined the Assumption of Mary as dogma, the only time that a pope has spoken ex cathedra since papal infallibility was explicitly declared.

In Roman Catholic ecclesiology

The dogmas and traditions of the Roman Catholic Church teach that the institution of the papacy was first mandated by Jesus:

"And I also say to you that you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of the netherworld will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven." (Matt.16:18-19)

Peter is thus the rock upon which Christ's church was built, and his successors at Rome stand in his position as the "vicar of Christ," acting on Jesus' behalf. The reference to the "keys of the kingdom of heaven" here are the basis for the symbolic keys often found in Catholic papal symbolism, such as in the Vatican Coat of Arms. John 21:15-17 further shows Jesus as appointing Peter as the primary "shepherd" of Christ's flock.

Election

In the early church, the popes were chosen by those senior clergymen resident in and near Rome. The elections were often contentious, resulting in schisms between factions, and sometimes involved imperial intervention. In 1059 the electors were restricted to the cardinals. The Second Council of Lyons (1274) decreed that the cardinal electors must meet within ten days of the pope's death and that they must remain in seclusion until a pope has been elected. By the mid-sixteenth century, the electoral process had more or less evolved into its present form. Under present canon law, the pope is elected by those cardinals who are under the age of 80.

The election of the pope normally takes place in the Sistine Chapel, in a sequestered meeting called a "conclave." Each cardinal elector writes the name of his choice on his ballot and pledges aloud that he is voting for "one whom under God I think ought to be elected." Each ballot is read aloud by the presiding cardinal, and voting continues until a pope is elected by a two-thirds majority.

Once the ballots are counted, they are burned in a special stove, with the smoke escaping through a small chimney visible from St. Peter's Square. If no pope is elected yet, a chemical compound is added to the fire to produce black smoke. When a vote is successful, the ballots are burned alone, sending white smoke through the chimney and announcing to the world the election of a new pope.

The dean of the College of Cardinals then asks the cardinal who has been successfully-elected two solemn questions. First he asks, "Do you freely accept your election?" If he replies with the word Accepto, his reign as pope begins at that instant. The dean then asks, "By what name shall you be called?" The new pope then announces the regnal name he has chosen for himself.

The new pope is led to a dressing room in which three sets of white papal vestments await: small, medium, and large. Donning the appropriate vestments and reemerging into the Sistine Chapel, the new pope is given the "Fisherman's Ring" receives the obeisance of his former colleagues.

The senior cardinal then announces from a balcony over St. Peter's Square: Annuntio vobis gaudium magnum! Habemus Papam! ("I announce to you a great joy! We have a pope!"). He then announces the new pope's Christian name along with the new name he has adopted as his regnal name. The pope's term of office is for life, and abdications have been rare.

Until 1978 the pope's election was followed in a few days by the Papal Coronation, which has since been suspended. For centuries, the papacy was dominated by Italians. Prior to the election of the Polish cardinal Karol Wojtyla as Pope John Paul II in 1978, the last non-Italian was Pope Adrian VI of the Netherlands, elected in 1522. John Paul II was followed by the German-born Benedict XVI, leading some to believe the age of Italian domination of the papacy to be over.

Abdication and death

The Code of Canon Law states, "If it happens that the Roman Pontiff resigns his office, it is required for validity that the resignation is made freely and properly manifested but not that it is accepted by anyone." The first pope to abdicate was Pontian in 235, although he did not do so freely, but under the duress of a sentence of exile. The canonical right has been exercised by Pope Celestine V in 1294 and Pope Gregory XII in 1409, who was the last pope to do so.

The current regulations regarding a papal interregnum were promulgated by John Paul II in his 1996 document Universi Dominici Gregis. During the vacancy caused by a pope's death the College of Cardinals is collectively responsible for the government of the Catholic Church and of the Vatican itself, under the direction of the Cardinal Chamberlain. Canon law specifically forbids the cardinals from introducing any innovation in the government of the Church during the vacancy of the Holy See.

A dead pope's body then lies in state for a number of days before being interred in the crypt of a leading church or cathedral. The popes of the twentieth century were all interred in St. Peter's Basilica. A nine-day period of mourning (novem dialis) follows after the interment of the late pope. Vatican tradition holds that no autopsy is to be performed on the body of a dead pope.

Titles

The titles of the Pope, in the order they are used in the Annuario Pontificio:

- Bishop of Rome

- Vicar of Christ

- Successor of the Prince of the Apostles

- Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church

- Primate of Italy

- Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Roman Province

- Sovereign of the State of the Vatican City

- Servant of the Servants of God

The Second Vatican Council confirmed the titles "Vicar of Christ" and "Successor of Peter" or "Successor of the Prince of the Apostles" as titles of the pope. The term "Supreme Pontiff" (Summus Pontifex) is another of the official titles of the Pope.

The ancient title Pontifex Maximus, which dates back to the early years of the Roman Republic, and, beginning with Julius Caesar, was associated with the Roman Emperors, until Gratian (359-383), who formally renounced the title.

The title "Servant of the Servants of God", although used by other church leaders including St. Augustine and St. Benedict, was first used by Pope St. Gregory the Great in his dispute with the Patriarch of Constantinople after the latter assumed the title "Ecumenical Patriarch." It was not reserved for the pope until the thirteenth century. Other titles commonly used are "His Holiness." "Holy Father."

Since, in the Eastern churches, the title "pope" does not unambiguously refer to the bishop of Rome, these churches often use the expression "pope of Rome" to refer to Roman pontiff.

The pope is addressed as "Your Holiness" or "Holy Father."

Regalia and insignia

- "Triregnum", also called the "tiara" or "triple crown", represents the pope's three functions as "supreme pastor," "supreme teacher," and "supreme priest." Recent popes have not worn the triregnum, although it remains the official symbol of the papacy. In liturgical ceremonies, today's popes wear an episcopal mitre (an erect cloth hat).

- Pastoral Staff topped by a crucifix, a custom established before the thirteenth century.

- The pallium, a circular band or stole worn around the neck the neck, breast and shoulders, with two pendants hanging down in front and behind, and is ornamented with six crosses. Until recently, the pallium worn by the pope was identical to those he granted to the primates, but in 2005 Pope Benedict XVI began to use a larger papal pallium adorned with red crosses instead of black.

- "Keys to the Kingdom of Heaven," the image of two keys, one gold and one silver. The silver key symbolizes the power to "bind and loose" on Earth, and the gold key the power to "bind and loose" in Heaven.

- Ring of the Fisherman, a gold ring decorated with a depiction of St. Peter in a boat casting his net, with the name of the reigning Pope around it.

- Umbraculum, a canopy or umbrella consisting of alternating red and gold stripes, which used to be carried above the pope in processions.

- Sedia gestatoria (now discontinued), a mobile throne carried by 12 footmen in red uniforms, accompanied by two attendants bearing fans made of white ostrich feathers, and sometimes a large canopy, carried by eight attendants. The use of the flabella was discontinued by Pope John Paul I, and the use of the sedia gestatoria was discontinued by Pope John Paul II, being replaced by the so-called Popemobile.

In heraldry, each pope has his own Papal Coat of Arms, which includes the aforementioned two keys behind the escutcheon (shield), and above them a silver triregnum with three gold crowns.

The flag most frequently associated with the pope is the yellow and white flag of Vatican City, with the arms of the Holy See on the right-hand side. Although Pope Benedict XVI replaced the triregnum with a mitre on his personal coat of arms, the triregnum has been retained on the flag.

Offices and residences

The pope's official seat or cathedral is the Basilica of St. John Lateran, and his official residence is the Palace of the Vatican. He also possesses a summer residence at Castel Gandolfo. Until the time of the Avignon Papacy, the residence of the Pope was the Lateran Palace, donated by the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great. The Pope's specific ecclesiastical jurisdiction, the Holy See, is distinct from his secular jurisdiction of Vatican City.

Infallible authority

The status and authority of the pope in the Catholic Church was dogmatically defined by the First Vatican Council on 18 July 1870. In its Dogmatic Constitution of the Church of Christ, the Council established that:

- Peter was established by Christ as the chief of the apostles, and the visible head of the whole church.

- It is heresy to deny that the Roman Pontiff is the successor of Peter holding the same primacy as him.

- It is also heresy to deny that pope's authority pertains not only matters of faith and morals, but also to the discipline and government of the Church throughout the whole world.

- The Roman Pontiff, when he speaks ex cathedra, operates with infallibility, and his decisions are unalterable.

The Second Vatican Council, while not repeating the anathemas directed by its predecessor against "heretics" who denied papal infallibility, nevertheless reaffirmed the doctrine. In its Dogmatic Constitution on the Church (1964), the council declared:

"...In matters of faith and morals, the bishops speak in the name of Christ and the faithful are to accept their teaching and adhere to it with a religious assent. This religious submission of mind and will must be shown in a special way to the authentic magisterium of the Roman Pontiff, even when he is not speaking ex cathedra... [H]is definitions, of themselves, and not from the consent of the Church, are justly styled irreformable, since they are pronounced with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, promised to him in blessed Peter, and therefore they need no approval of others, nor do they allow an appeal to any other judgment.

The papacy today

While the papacy has lost considerable political power in recent centuries, its prestige as a moral and spiritual power has grown considerable. The pope remains the sole ruler of the Catholic Church, which is not only the largest Christian denomination, but the largest organized body of any world religion, with over one billion members, accounting for approximantly one in six of the world's population. No longer a primarily European faith, the majority the pope's flock hail from Latin America, Africa, and Asia. The papacy also controls or supervises a vast network of Catholic financial institutions, schools, monasteries, charitable organizations, museums, hospitals, and social groups.

The pope commands huge audiences of up to and over a million people when he travels, notably included many young people. His moral teachings remain highly influential. Politically, the papacy of John Paul II is considered to have been a major factor in the fall of he Soviet Union.

The pope is a major figure in the ecumenical movement, whose voice commands the attention of leaders of virtually every faith. He frequently meets with the presidents of the greatest nations of the world. It is no exaggeration to say that the papacy remains one of the world's most important world institutions today.

See also

- List of popes

- Caesaropapism

- Investiture Controversy

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Loomis, Louise Ropes (2006). The Book of the Popes (Liber Pontificalis): To the Pontificate of Gregory I. Evolution Publishing: Merchantville, NJ. ISBN 1-889758-86-8. . Reprint of an English translation originally published in 1916.

- Ludwig von Pastor, History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages; Drawn from the Secret Archives of the Vatican and other original sources, 40 vols. St. Louis, B. Herder 1898 - (World Cat entry)

- Hartmann Grisar (1845-1932), History of Rome and the Popes in the Middle Ages, AMS Press; Reprint edition (1912). ISBN 0-404-09370-1

- James Joseph Walsh, The Popes and Science; the History of the Papal Relations to Science During the Middle Ages and Down to Our Own Time, Fordam University Press, 1908, reprinted 2003, Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-3646-9

Further reading

- Brusher, Joseph H. Popes Through The Ages. Princeton: D. Van Nostland Company, Inc. 1959.

- Chamberlain, E.R. The Bad Popes. 1969. Reprint: Barnes and Noble. 1993.

- Dollison, John Pope - Pourri. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1994.

- Kelly, J.N.D. The Oxford Dictionary of Popes. Oxford: University Press. 1986. ISBN 0-19-213964-9

- Maxwell-Stuart, P.G. Chronicles of the Popes - The Reign By Reign Record of The Papacy From St. Peter To The Present. London: Thames and Hudson. 1997. ISBN 0-500-01798-0

External links

- The Holy See - The Holy Father – website for the past and present Holy Fathers (since Leo XIII)

- The Holy Father's 2008 Prayer Intentions

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry

- Pope Endurance League - Sortable list of Popes

- Scholarly articles on the Roman Catholic Papacy from the Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary Library

- Data Base of more than 23,000 documents of the Popes in latin and modern languages

| ||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.