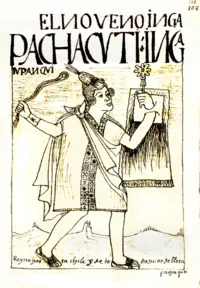

Pachacuti

Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (or Pachacutec) was the ninth Sapa Inca (1438 - 1471/1472) of the Kingdom of Cusco, which he transformed into the empire Tawantinsuyu. In Quechua, Pachakutiq means "He who remakes the world." During his reign, Cuzco grew from a hamlet into an empire that could compete with, and eventually overtake, the Chimu. He began an era of conquest that, within three generations, expanded the Inca dominion from the valley of Cuzco to nearly the whole of civilized South America. His conquests where so successful that he is sometimes referred to as "The Napoleon of the Andes." When Pachacuti died in 1471, the empire stretched from Chile to the south and Ecuador to the north also including the modern countries of Peru and Bolivia as well as most of northern Argentina.

Pachacuti's empire was wealthy and well-organized, with generally humane treatment of its people, including the vanquished. The empire was really a federal system. It took the Spanish just eight years to all but destroy the richest culture in the Americas, replacing it with a much less just system. Indeed, it has been argued that the Inca's government allowed neither misery nor unemployment, as production, consumption, and demographic distribution reached almost mathematical equilibrium. The main legacy of the civilization that Pachacuti did so much to build lies in its power to inspire, including that of later resistance groups in the area against Spanish rule.

Lineage

Pachacuti, son of Inca Viracocha, was the fourth of the Hanan dynasty. His wife's name is given as Mama Anawarkhi or Coya Anahurque. He had two sons: Amaru Yupanqui and Tupac Inca Yupanqui. Amaru, the older son, was originally chosen to be co-regent and eventual successor. Pachacuti later chose Tupac because Amaru was not a warrior.[1]

Succession

Pachacuti's given name was Cusi Yupanqui and he was not supposed to succeed his father Inca Viracocha who had appointed his brother Urco as crown prince. However in the midst of an invasion of Cuzco by the Chankas, the Incas' traditional tribal archenemies, Pachacuti had a real opportunity to demonstrate his talent. While his father and brother fled the scene Pachacuti rallied the army and prepared for a desperate defense of his homeland. In the resulting battle the Chankas were defeated so severely that legend tells even the stones rose up to fight on Pachacuti's side. Thus, "The Earth Shaker" won the support of his people and the recognition of his father as crown prince and joint ruler.

The Ninth Sapa Inca

After his father's death, Pachacuti became sole ruler of the Incan empire. Immediately, he initiated an energetic series of military campaigns which would transform the small state around Cuzco into a formidable nation. This event, says Brundage, "is presented to us in the sources as the most striking event in all Inca history—the year one, as it were."[2] His conquests in collaboration with Tupac Yupanqui (Pachacuti's son and successor) where so successful that the ninth Incan emperor is sometimes referred to as "Napoleon of the Andes." When Pachacuti died in 1471 the empire stretched from Chile to the south and Ecuador to the north also including the modern countries of Peru and Bolivia as well as most of northern Argentina.

Pachacuti also reorganized the new empire, the Tahuantinsuyu or "the united four provinces." Under his system, there were four apos that each controlled one of four provinces (suyu). Below these governors were t'oqrikoq, or local leaders, who ran a city, valley, or mine. By the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru, each apo had around 15 t'oqrikoq below him, but we can assume there were fewer when Pachacuti first organized this system. He also established a separate chain of command for the army and priesthood to establish a system of checks and balances on power.

Pachacuti dispatched spies to regions he wanted in his empire. Their job was to send back intelligence reports on their political organization, military might, and wealth. Pachacuti then communicated with the leaders of these lands, extolling the benefits of joining his empire. He would offer them presents of luxury goods, such as high quality textiles, and promise them that they would be materially richer as subject rulers of the Inca. Most accepted his rule as a fait accompli and acquiesced peacefully, so military conquest was not necessary. There is some similarity with how the Roman Emperors thought people should welcome their rule, as bringing benefits, good governance and the pax romana. The ruler's children would then be brought to Cuzco to be taught about Inca administration systems before returning to rule their native lands. This allowed the Inca to indoctrinate the former ruler's children into the Inca nobility, and, with luck, marry their daughters into families at various corners of the empire.

Pachacuti rebuilt much of Cuzco, designing it to serve the needs of an imperial city, and indeed as a representation of the empire. There was a sector of the city for each suyu, centering on the road leading to that province; nobles and immigrants lived in the sector corresponding to their origin. Each sector was further divided into areas for the hanan (upper) and hurin (lower) moieties. The Inca and his family lived in the center; the more prestigious area. Many of the most renowned monuments around Cuzco, such as the great sun temple of Coricancha or the "fortress" of Sacsayhuamán, were constructed during Pachacuti's reign.

Despite Pachacuti's political and military talents, he did not improve upon the system of choosing the next Inca. His son became the next Inca without any known dispute after Pachacuti died in 1471 due to a terminal illness, but in future generations the next Inca had to gain control of the empire by winning enough support from the apos, priesthood, and military to either win a civil war or intimidate anyone else from trying to wrest control of the empire. Pachacuti is also credited with having displaced hundreds of thousands in massive programs of relocation and resettling to occupy the remotest corners of his empire. These forced colonists where called mitimaes and represented the lowest place in the Incan social ladder.

In many respects, however, once subdued, people and their rulers were treated with respect. Rulers were frequently left in post; their subject people's cultures were assimilated, not destroyed.

Machu Picchu is believed to date to the time of Pachacuti.

Pachacuti was a poet and author of the Sacred Hymns of the Situa.[3]

Legacy

Pachacuti is considered as somewhat of a national hero in modern Peru. During the 2000 Presidential elections candidate, the mestizo Indian population gave Alejandro Toledo the nickname Pachacuti. Tradition celebrates his "patriotism" and his "piety" and "the incompetency of the incumbent king."[4] he is often described as an "enlightened ruler."[5]

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived and began their conquest of the Empire Pachacuti did so much to create, the Spanish saw little or no reason to preserve anything they encountered in Inca civilization. They plundered its wealth and left the civilization in ruin. The civilization's sophisticated road and communication system and governance were no mean accomplishments. They were greedy for the wealth, which existed in fabulous proportion, not the culture. Yet, through the survival of the language and of a few residual traces of the culture, the civilization was not completely destroyed. The great and relatively humane civilization of the Incas' main legacy is inspirational, residing in the human ability to imagine that such a fabulously rich, well-ordered, and generally humane society once existed, high up in the Andean hills.

Notes

- ↑ Rostworowski, Inca Succession, The Incas. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- ↑ Brundage, 95.

- ↑ Curl, Sacred Hymns of the Situa. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- ↑ Brundage, 87.

- ↑ Bingham, 308.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bingham, Hiram. Inca Land: Explorations in the Highlands of Peru. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1922. Dodo Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1409990055

- Brundage, Burr Cartwright. Empire of the Inca. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985. ISBN 9780806119243.

- Curl, John trans. Sacred Hymns of the Situa. red-coral.net. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- MacCormack, Sabine. On the Wings of Time: Rome, the Incas, Spain, and Peru. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780691126746

- Rostworowski, Maria. "Inca Succession." The Incas. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Sarmiento de Gamboa, Pedro, Brian S. Bauer, and Vania Smith. The History of the Incas. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1463688653

| Preceded by: Viracocha |

Sapa Inca 1438-71 |

Succeeded by: Túpac Inca Yupanqui |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.