Mohenjo-daro

| Archaeological Ruins at Moenjodaro* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii |

| Reference | 138 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

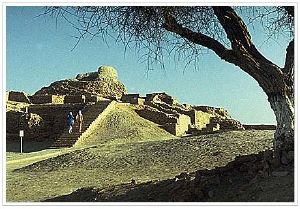

Mohenjo-daro (Urdu: موئن جودڑو, Sindhi: موئن جو دڙو, English: Mound of the dead) - a city of the Indus Valley Civilization built around 2600 B.C.E., located in the Sindh Province of Pakistan. That ancient five thousand year old city constitutes the largest of Indus Valley, widely recognized as one of the most important early cities of South Asia and the Indus Valley Civilization. Mohenjo Daro, one of the world’s first cities and contemporaneous with ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, has been sometimes referred to as "An Ancient Indus Valley Metropolis."

History

Mohenjo Daro, built around 2600, had been abandoned around 1700 B.C.E.. Sir John Marshall's archaeologists rediscovered it in the 1920s. His car, still in the Mohenjo-daro museum, shows his presence, struggle, and dedication for Mohenjo-daro. Ahmad Hasan Dani and Mortimer Wheeler carried out further excavations in 1945. Mohenjo-daro in ancient times had been most likely the administrative center of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization. The most developed and advanced city in South Asia during its peak, Mohenjo-daro's planning and engineering showed the importance of the city to the people of the Indus valley.[1]

The Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300–1700 B.C.E., flowered 2600–1900 B.C.E.), abbreviated IVC, had been an ancient riverine civilization that flourished in the Indus river valley in Pakistan and north-west India. "Harappan Civilisation had been another name for this civilization.

The Indus Valley civilization was one of the most ancient civilizations, on the banks of Indus River. The Indus culture blossomed over the centuries and gave rise to the Indus Valley Civilization around 3000 B.C.E. The civilization spanned much of Pakistan, but suddenly went into decline around 1800 B.C.E. Indus Civilization settlements spread as far south as the Arabian Sea coast of India, as far west as the Iranian border, and as far north as the Himalayas. Among the settlements were the major urban centers of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, as well as Lothal.

The Mohenjo-daro ruins were once the center of this ancient society. At its peak, some archaeologists opine that the Indus Civilization may have had a population of well over five million.

To date, over a thousand cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the Indus River valley in Pakistan and north western India.

The language of the Indus Civilization has yet to be deciphered, and the real name of the city as of other excavated cities in Sindh, Punjab and Gujarat, is unknown. "Mohenjo-daro" is Sindhi for "Mound of the Dead." (The name is also seen with slight variants such as Moenjodaro.)

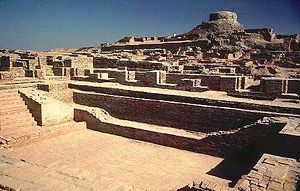

Mohenjo-daro is a remarkable construction, considering its antiquity. It has a planned layout based on a grid of streets, which were laid out in perfect patterns. At its height the city probably had around 35,000 residents. The buildings of the city were particularly advanced, with structures constructed of same-sized sun dried bricks of baked mud and burned wood.

The public buildings of these cities also suggest a high degree of social organization. The great granary at Mohenjo-daro is designed with bays to receive carts delivering crops from the countryside, and there are ducts for air to circulate beneath the stored grain to dry it.

Close to the granary, there is a building similarly civic in nature - a great public bath, with steps down to a brick-lined pool in a colonnaded courtyard The elaborate bath area was very well built, with a layer of natural tar to keep it from leaking, and in the center was the pool. Measuring 12m x 7m, with a depth of 2.4m, it was likely used for religious or spiritual ceremonies.

The houses were protected from noise, odors, and thieves. This urban plan included the world's first urban sanitation systems.

Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. Some of the houses included rooms that appear to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes. A variety of buildings were up to two stories high.

Being an agricultural city, it also featured a large well, and central marketplace. It also had a building with an underground furnace (hypocaust), possibly for heated bathing.

Defensively Mohenjo-daro was a well fortified city. Lacking city walls, it did have towers to the west of the main settlement, and defensive fortifications to the south. Considering these fortifications and the structure of other major Indus valley cities like Harappa, lead to the question of whether Mohenjo-daro was an administrative center. Both Harappa and Mohenjo-daro share relatively the same architectural layout, and were generally not heavily fortified like other Indus Valley sites. It is obvious from the identical city layouts of all Indus sites, that there was some kind of political or administrative centrality, however the extent and functioning of an administrative center remains unclear. .

Mohenjo-daro was successively destroyed and rebuilt at least seven times. Each time, the new cities were built directly on top of the old ones. Flooding by the Indus is thought to have been the cause of destruction.

The city was divided into two parts, the Citadel and the Lower City. Most of the Lower City is yet uncovered, but the Citadel is known to have the public bath, a large residential structure designed to house 5,000 citizens and two large assembly halls.

Mohenjo-daro, Harappa and their civilization, vanished without trace from history until discovered in the 1920s. It was extensively excavated in the 1920s, but no in-depth excavations have been carried out since the 1960s.

Civilization

Artifacts

The Dancing girl found in Mohenjo Daro is an interesting artifact that is some 4500-years old. The 10.8 cm long bronze statue of the dancing girl was found in 1926 from a house in Mohenjo Daro. She was British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler's favorite statuette, as he said in this quote from a 1973 television program:

- "There is her little Baluchi-style face with pouting lips and insolent look in the eye. She's about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl perfectly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There's nothing like her, I think, in the world."

John Marshall, one of the excavators at Mohenjo-Daro, described her as a vivid impression of the young ... girl, her hand on her hip in a half-impudent posture, and legs slightly forward as she beats time to the music with her legs and feet.[2]

The artistry of this statuette is recognizable today and tells of a strange, but at least fleetingly recognizable past. As author Gregory Possehl says, "We may not be certain that she was a dancer, but she was good at what she did and she knew it." The statue could well be of some queen or other important woman of the Indus Valley Civilization judging from the authority the figure commands.

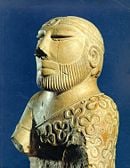

Seated male sculpture, or "Priest King" (even though there is no evidence that either priests or kings ruled the city). This 17.5 cm tall statue is another artifact which has become a symbol for the Indus valley civilization. Archaeologists discovered the sculpture in Lower town at Mohenjo-Daro in 1927. It was found in an unusual house with ornamental brickwork and a wall niche and was lying between brick foundation walls which once held up a floor.

This bearded sculpture wears a fillet around the head, an armband, and a cloak decorated with trefoil patterns that were originally filled with red pigment.

The two ends of the fillet fall along the back and though the hair is carefully combed towards the back of the head, no bun is present. The flat back of the head may have held a separately carved bun as is traditional on the other seated figures, or it could have held a more elaborate horn and plumed headdress.

Two holes beneath the highly stylized ears suggest that a necklace or other head ornament was attached to the sculpture. The left shoulder is covered with a cloak decorated with trefoil, double circle and single circle designs that were originally filled with red pigment. Drill holes in the center of each circle indicate they were made with a specialized drill and then touched up with a chisel. Eyes are deeply incised and may have held inlay. The upper lip is shaved and a short combed beard frames the face. The large crack in the face is the result of weathering or it may be due to original firing of this object.

Current UNESCO Status

Mohenjo-daro is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The most extensive recent work at the site has focused on attempts at conservation of the standing structures, undertaken by UNESCO in collaboration with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, as well as various foreign consultants.

In December 1996, preservation work at the 500-acre site suspended after funding from the government and international organisations ran out, according to a resident archaeologist.

However in April 1997, the UN Educational, Scientific and Culture Organization (UNESCO) funded $10 million to a project to be conducted over two decades in order to protect the Mohenjo-daro ruins from flooding. This project has been a success so far.

UNESCO's efforts to save Mohenjo-daro was one of the key events that led the organization to establish World Heritage Sites.

See also

- Indus Valley Civilization

- Harappa

- Chanhudaro

- Sindh

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ A H Dani (1992), Critical Assessment of Recent Evidence on Mohenjodaro, Second International Symposium on Mohenjodaro, 24-27. "February.

- ↑ Gregory L. Possehl (2002), The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, AltaMira Press. ISBN 978-0759101722

External links

- Harappa

- archaeology.about.com

- Harappa geography

- tourtopakistan

- HistoryWorld

- Mohenjo-Daro

- Mohenjodaro

- Civilizations in Pakistan

- Moenjodaro lifestyle

- The Telegraph

| |||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.