Minotaur

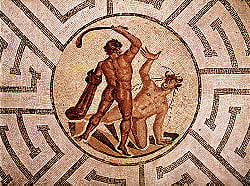

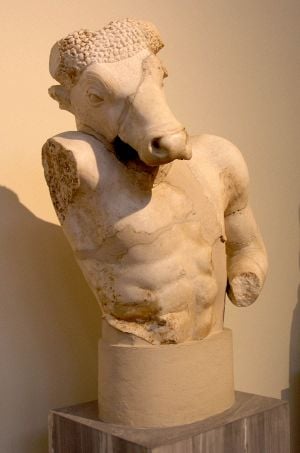

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur was a mythical creature that was part man and part bull. It was kept by King Minos of Crete in the center of a "labyrinth," an elaborate maze-like construction designed by the architect Daedalus specifically to hold the Minotaur. According to legend, the Minotaur required human sacrifices on a regular basis. Theseus volunteered to be sacrificed, and with the help of Daedalus, was able to slay the Minotaur and escape the maze. The battle scene between Theseus and the Minotaur has been captured in art by many artists over the centuries.

This tale contains much that touches the essence of human existence. Like the Minotaur, people are all in some sense monstrous, unlovable, and unable to love each other truly. We too, come from a lineage that came about through disobedience to God and an unholy union with the Devil. Human history shows that we live as if lost in a maze, confused and unable to find our way back to the ideal, harmonious world of happiness and peace. Yet, we hope that our fate will not be that of the Minotaur, to be killed at the hands of the "hero" but rather to be restored to life.

Etymology

The Minotaur was a creature that was part man and part bull. "Minotaur" in Greek (Μινόταυρος, Minótauros) translates as "Bull of Minos."[1] It lived at the center of an elaborate maze-like construction built for King Minos of Crete, specifically to trap the Minotaur. The bull was known in Crete as Asterion, a name shared with Minos's foster father.

Origin

How the myth of the Minotaur developed is not entirely clear. It is a Greek myth, involving a different civilization, the Minoans, which was actually quite a common occurrence in ancient Greek lore. Several other mythical creatures were from far away places. It is generally believed that the ruin of Knossos on the island of Crete is the capital of the ancient Minoan empire. However, no maze has been discovered there. Still, the large palaces are so elaborate that it would have been easy to become confused and lost, which may explain part of the myth.

While the term "labyrinth" is often used interchangeably with "maze," modern scholars of the subject use a stricter definition: a maze is a tour puzzle in the form of a complex branching passage with choices of path and direction; while a single-path ("unicursal") labyrinth has an unambiguous through-route to the center and back and is not designed to be difficult to navigate. This unicursal design was wide-spread in artistic depictions of the Minotaur's labyrinth even though both logic and literary descriptions of it make it clear that the Minotaur was trapped in a multicursal maze.[2]

A historical explanation of the myth refers to the time when Crete was the main political and cultural potency in the Aegean Sea. As the fledgling Athens (and probably other continental Greek cities) was under tribute to Crete, it can be assumed that such tribute included young men and women for sacrifice. This ceremony was performed by a priest disguised with a bull head or mask, thus explaining the imagery of the Minotaur. It may also be that this priest was son to Minos. Once continental Greece was free from Crete's dominance, the myth of the Minotaur worked to distance the forming religious consciousness of the Hellene poleis from Minoan beliefs.

The origin of the Minotaur is well accepted in Greek mythology without many variations. Before Minos became king, he asked the Greek god Poseidon for a sign to assure him that he, and not his brother, was to receive the throne (other accounts say that he boasted that the gods wanted him to be king). Poseidon agreed to send a white bull as a sign, on condition Minos would sacrifice the bull to the god in return. Indeed, a bull of unmatched beauty came out of the sea. King Minos, after seeing it, found it so beautiful that he instead sacrificed another bull, hoping that Poseidon would not notice. Poseidon was enraged when he realized what had been done, so he caused Minos's wife, Pasiphaë, to fall deeply in love with the bull. Pasiphaë tried to seduce the bull without success, until she requested help from Daedalus the great architect from Crete. Daedalus built a hollow wooden cow, allowing Pasiphaë to hide inside. The queen approached the bull inside the wooden cow and the bull, confused by the perfection of the costume, was conquered.

The result of this union was the Minotaur (the Bull of Minos), who some say bore the proper name Asterius ("Starry One"). The Minotaur had the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. Pasiphaë nursed him in his infancy, but he grew and became ferocious. Minos, after receiving advice from the Oracle at Delphi, had Daedalus construct a gigantic labyrinth to hold the Minotaur. Its location was near Minos' palace in Knossos. In some accounts, the white bull went on to become the Cretan Bull captured by Heracles as one of his labors.[3]

Theseus and the Minotaur

During his reign as king, Minos required that seven Athenian youths and seven maidens, drawn by lots, be sent every ninth year (some accounts say every year) to be devoured by the Minotaur. The exact reasoning for this sacrifice is not agreed upon. Some say it was Athenian payment for the death of Minos's son in a war, whiles others believe that Minos had convinced the Athenians that the sacrifice was necessary in order to thwart a mysterious plague that was ravaging Athens. In either case, it is clear that the Athenians were not happy with the arrangement.

When the time for the third sacrifice came, Theseus volunteered to go to slay the monster. He promised to his father, Aegeus, that he would put up a white sail on his journey back home if he was successful. Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, fell in love with Theseus and compelled Daedalus to help Theseus escape the labyrinth. In most accounts he is given a ball of thread, allowing him to retrace his path after he killed the minotaur, which he did by sneaking up on the creature while it slept and beating it to death with his fist. Theseus was also able to lead the other six Athenians safely from the labyrinth.

Theseus took Ariadne with him from Crete, but abandoned her en-route to Athens. Generally this is said to happen on the island of Naxos. According to Homer, she was killed by Artemis upon the testimony of Dionysus. However, later sources report that Theseus abandoned her as she slept on the island of Naxos, and there became the bride of Dionysus. The epiphany of Dionysus to the sleeping Ariadne became a common theme in Greek and Roman art, and in some of these images Theseus is shown running away.

On his return trip, Theseus forgot to change the black sails of mourning for white sails of success, so his father, overcome with grief, lept off the cliff top from which he had kept watch for his son's return every day since Theseus had departed into the sea. The name of the "Aegean" sea is said to derive from this event.

Minos, angry that Theseus was able to escape, imprisoned Daedalus and his son Icarus in a tall tower. They were able to escape by building wings for themselves with the feathers of birds that flew by, but Icarus died during the escape as he flew too high (in hope of seeing Apollo in his sun chariot) and the wax that held the feathers in the wings melted in the heat of the sun.

Cultural Representations

The contest between Theseus and the Minotaur has been frequently represented in art, both in Classical Greek styles as well the Renaissance artwork of Europe.[4] The ruins of Knossos, although not of Greek origin, also portray the myth, at times vividly in its many wall murals. A Knossian didrachm exhibits on one side the labyrinth, on the other the Minotaur surrounded by a semicircle of small balls, probably intended for stars; it is to be noted that one of the monster's names was Asterius.[5]

No artist has returned so often to the theme of the Minotaur as Pablo Picasso.[6] André Masson, René Iché, and Georges Bataille suggested to Albert Skira the title Le Minotaure for his art publication, which ran from 1933 until it was overtaken by war in 1939; it resurfaced in 1946 as Le Labyrinthe.

In contemporary times the minotaur has often been seen in a variety of fantasy-based sub-culture, such as comic books and video and role-playing games, often mismatched with other such mythological creatures as stock-characters, a contemporary method of blending the new with the old. The labyrinth, although in present times not always correlated to the minotaur, is often used in fantasy as well. In fact, the idea of a labyrinth (or more properly a maze), and all the deception and danger that heroes face within one, comes directly from the legend of the Minotaur.

Notes

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary.1971. ISBN 019861117X

- ↑ Doob, Penelope Reed, The Idea of the Labyrinth: from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages. ISBN 0-8014-8000-0

- ↑ Hamilton, Edith, Mythology. 1942. ISBN 0316341142

- ↑ Parada, Carlos, and Förlag, Maicar, Minotaur. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ↑ Ancienent-Greece.org, Knossos. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ↑ Ries, Martin "Picasso and the Myth of the Minotaur." Art Journal. 32, No. 2, 1972. p.142-145.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths: Complete Edition. Penguin. 1993. ISBN 0140171991

- Hamilton, Edith. Mythology. Little, Brown and Company. 1942. ISBN 0316341142

- Macgillivray, J.A. Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. Hill & Wang. 2000. ISBN 0809030357

External Links

All links retrieved November 7, 2014.

- Theoi Project. Minotauros.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.