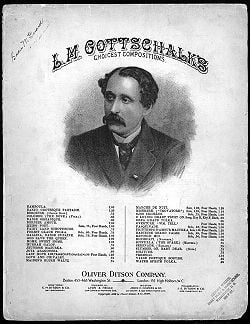

Louis Moreau Gottschalk

Louis Moreau Gottschalk (May 8, 1829 – December 18, 1869) was an American composer and pianist, best known as a virtuoso performer of his own romantic piano music pieces. Though he only lived for forty years, he became the most prominent American composer and pianist of his time. His biographer, Frederick Starr, an American anthropologist, attested Gottschalk had achieved an astonishing list of "firsts."

Starr wrote, "He was the first American composer to be hailed in Europe, the first American piano virtuoso to be acclaimed by Frédéric Chopin, (Chopin predicted that he would become the 'king of pianists'), the first American composer to erase the hard line dividing 'serious' and 'popular' genres, the first to introduce American themes into European classical music, the first Pan-American artist in any field and was among the first American artists to champion the causes of abolitionism, public education, and popular democracy."

Perhaps his greatest contribution to American music was incorporating the syncopated rhythmic elements of Caribbean and Latin folk music into his own. As Frederick Starr pointed out, these rhythmic elements "anticipate ragtime and jazz by a half century." It could be said that jazz is a progeny, at least in terms of its rhythmic characteristics, of Gottschalk's Latin-influenced compositions.

Gottschalk understood the emotional and spiritual aspects of music, and echoed St. Augustine's views, when he stated, "Music is a thing eminently sensuous. Certain combinations move us, not because they are ingenious, but because they affect our nervous system in a certain way." Like Augustine, Gottschalk viewed music as a vehicle that could touch emotions and affect consciousness in profound ways.

Biography

Gottschalk was born to a Jewish businessman from London and a white Creole Haitian in New Orleans, where he was exposed to a wide variety of musical traditions. His family lived for a time in a tiny cottage at Royal & Esplanade in the Vieux Carré, and Louis subsequently moved in with relatives on 518 Conti Street. His Grandmother Buslé and his nurse Sally were both natives of Saint-Domingue. He began his piano studies when he was four years old and was soon recognized as a wunderkind by the New Orleans bourgeois establishment. In 1840, he gave his informal public debut at the new St. Charles Hotel.

Only two years later, he left the United States and sailed to Europe, realizing that a European classical music training would be required to fulfill his musical ambitions. The Conservatoire de Paris, however, initially rejected his application, and Gottschalk only gradually gained access to the musical establishment through friends of his family.

It was while in Europe that musical luminaries such as Frederic Chopin and Hector Berlioz recognized Gottschalk's prodigious gifts. Beriloz became a mentor to the young American's first compositions for orchestra and would proclaim that Gottschalk was "one of a very small number who possess all the different elements of a consummate pianist---all the faculties which surround him with an irrestible prestige and give him a sovereign power."

Upon his return to the United States in 1853, Gottschalk traveled extensively making a lengthy trip to Cuba in 1854, marking the beginning of a series of trips to Central and South America. By the 1860s, Gottschalk had established himself as the foremost pianist in the New World. Gottschalk's fame and public appeal was such that P.T. Barnum offered him the princely fee of $20,000 to tour under his management, but the young pianist/composer declined, preferring to tour on his own, often presenting concerts in rural settings such as farms or mining camps.

Although born in New Orleans, he was a supporter of the Union cause during the American Civil War, and even though he returned to his native city only occasionally for concerts, he always introduced himself as a New Orleanian. In 1865, he was forced to leave the United States as the result of what was regarded as a scandalous affair with a student at the Oakland Female Seminary.

He chose to again travel to South America, where he continued to give frequent concerts. During one of these concerts, in Rio de Janeiro on November 24, 1869, he collapsed, the result of a burst appendix. Much was made of the fact that, just before his collapse, he had finished playing his romantic piece Morte!! (interpreted as "she is dead"), although the actual collapse occurred just as he started to play his celebrated piece Tremolo.

Gottschalk never recovered from the collapse and three weeks later, on December 18, 1869, died at his hotel in Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. His remains were subsequently returned to the United States and are presently interred at the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. His burial spot was originally marked by a magnificent monument, which has eroded considerably over the years, and the Green-Wood is actively seeking donations to restore the monument, the cost of which they estimate at $75,000.[1]

Works

Gottschalk's music was extremely popular during his lifetime, and his earliest compositions created a sensation in Europe. Early pieces like Media:Le Bananier and Bamboula were based on Gottschalk's memories of the music he heard during his youth in Louisiana, and were regarded as magnificently exotic by the critics of the time. Throughout his life, Gottschalk used a variety of non-traditional, ethnically derived material for many of his compositions. Notable examples include the Souvenir de Porto Rico and The Banjo, Grotesque Fantasie. These ethnic and national-character pieces are regarded as his finest and most important work in that they fuse folk and traditional elements in masterful ways. His most famous orchestral composition, the Symphonie romantique, Noche en los Tropicos, is also a brilliant synthesis of European and South American melodic and rhythmic characteristics.

Gottschalk was also very successful as a composer of more traditional "salon music." Sentimental pieces like The Dying Poet were favorites of countless (mostly female) amateur pianists. His most famous work in this vein is The Last Hope, Religious Meditation, which enjoyed a spectacular success during Gottschalk's life, and for several decades afterward. Most critics regard Gottschalk's salon compositions as dated, musically shallow, and insignificant in comparison with his more distinctive American ethnic music.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, his music had fallen out of favor and was largely neglected in the first half of the century. However after World War II, there was an upsurge of interest in his works as musicians, critics, and the general public rediscovered the innovation and sophistication of his unique musical voice. A Gottschalk revival took place in the decades after World War II as pianists and conductors in the United States became infatuated once again with the music of this American original. Not surprisingly, the American Ballet Theater of New York, commissioned composer Jack Elliot to arrange several of Gottschalk's important works for the dance stage. These works, with their infectious dance rhythms and ebullient dispositions, remain a staple of ABT's repertory.

Listening

- A Night in the Tropics, The Hot Springs Music Festival Orchestra, NAXOS CD 8.559036

Notes

- ↑ The Green-Wood Cemetary, Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Retrieved January 3, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ewen, David. American Composers: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1982.

- Loggins, Vernon. Where the Word Ends: The Life of Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1958.

- Perone, James, E. Louis Moreau Gottschalk: A Bio-Bliography. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2002. ISBN 0-313-31824-7

- Starr, S. Frederick. Bamboula!: The Life and Times of Louis Moreau Gottschalk. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-195-07237-5

External links

All links retrieved December 24, 2013.

- Home Page, Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

- Adam Kirsch, June 7, 2006; "Diary of a 'One-Man Grateful Dead'" The New York Sun.

- The Dying Poet, Op.110 (Gottschalk, Louis Moreau), IMSLP.

- Kunst der Fuge: Louis Moreau Gottschalk—MIDI files (piano works).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.