John McCain

| John McCain | |

United States Senator from Arizona | |

United States Senator

| |

| In office January 3, 1987 – August 25, 2018 | |

| Preceded by | Barry Goldwater |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Jon Kyl |

Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee

| |

| In office January 3, 2015 – August 25, 2018 | |

| Preceded by | Carl Levin |

| Succeeded by | Jim Inhofe |

Chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee

| |

| In office January 3, 2005 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Ben Nighthorse Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Byron Dorgan |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 1997 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel Inouye |

| Succeeded by | Ben Nighthorse Campbell |

Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee

| |

| In office January 3, 2003 – January 3, 2005 | |

| Preceded by | Fritz Hollings |

| Succeeded by | Ted Stevens |

| In office January 20, 2001 – June 3, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Fritz Hollings |

| Succeeded by | Fritz Hollings |

| In office January 3, 1997 – January 3, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Larry Pressler |

| Succeeded by | Fritz Hollings |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Arizona's 1st district

| |

| Preceded by | John Jacob Rhodes |

| Succeeded by | John Jacob Rhodes III |

| Born | August 29 1936 Coco Solo, Panama Canal Zone, U.S. |

| Died | August 25 2018 (aged 81) Cornville, Arizona, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Carol Shepp (m. 1965; div. 1980) Cindy Hensley (m. 1980) |

| Children | 7, including Meghan |

| Website | John Sidney McCain III |

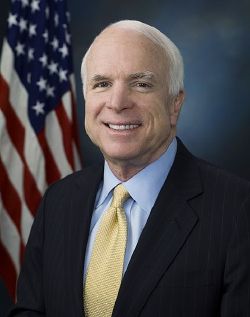

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American politician and naval officer. He was a prisoner of war during the Vietnam War for five and a half years. He served as a United States Senator from Arizona from 1987 until his death. He previously served two terms in the United States House of Representatives and was the Republican nominee for President of the United States in the 2008 election, which he lost to Barack Obama.

After being investigated and largely exonerated in a political influence scandal of the 1980s as a member of the Keating Five, he made campaign finance reform one of his signature concerns, which eventually resulted in passage of the McCain–Feingold Act in 2002. He was also known for his work in the 1990s to restore diplomatic relations with Vietnam, and for his belief that the Iraq War should have been fought to a successful conclusion.

While generally adhering to conservative principles, McCain also had a media reputation as a "maverick" for his willingness to disagree with his party on certain issues. He became a key figure in the Senate for his work in a number of bipartisan groups of senators and for negotiating deals on certain issues in an otherwise partisan environment. A strong patriot, McCain worked his whole life in service to his country, reducing his role in the Senate only after being diagnosed and treated for brain cancer which ultimately took his life.

Life

John Sidney McCain III was born on August 29, 1936, at Coco Solo Naval Air Station in the Panama Canal Zone, to naval officer John S. McCain Jr. and Roberta (Wright) McCain. He had a younger brother named Joe and an elder sister named Sandy.[1] At that time, the Panama Canal was under U.S. control.[2]

McCain's father and his paternal grandfather, John S. McCain Sr., were also Naval Academy graduates and both became four-star United States Navy admirals.[3] The McCain family followed his father to various naval postings in the United States and the Pacific.

In 1951, the family settled in Northern Virginia, and McCain attended Episcopal High School, a private preparatory boarding school in Alexandria. There, he excelled at wrestling, graduating in 1954.[4] He referred to himself as an Episcopalian as recently as June 2007, after which date he said he came to identify as a Baptist.[5]

Following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, McCain entered the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. He was a friend and informal leader there for many of his classmates,[6] and sometimes stood up for targets of bullying.[3] He also became a lightweight boxer.[7]

McCain graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1958 and followed his father and grandfather—both four-star admirals—into the United States Navy. He became a naval aviator and flew ground-attack aircraft from aircraft carriers.

At age 28 on July 3, 1965, McCain married Carol Shepp, a model from Philadelphia, and adopted her two young children, Douglas and Andrew.[8] He and Carol then had a daughter named Sidney.

During the Vietnam War, he was almost killed in the 1967 USS Forrestal fire. Then, while on a bombing mission during Operation Rolling Thunder over Hanoi in October 1967, McCain was shot down, seriously injured, and captured by the North Vietnamese. He was a prisoner of war until 1973. McCain experienced episodes of torture and refused an out-of-sequence early repatriation offer. The wounds that he sustained during the war left him with lifelong physical disabilities.

McCain was reunited with his family when he returned to the United States. However, the marriage did not survive, and McCain admitted to having extramarital affairs. Regarding his first marriage, McCain wrote in his memoir Worth the Fighting For that he "had not shown the same determination to rebuild (his) personal life" as he had shown in his military career:

Sound marriages can be hard to recover after great time and distance have separated a husband and wife. We are different people when we reunite... But my marriage's collapse was attributable to my own selfishness and immaturity more than it was to Vietnam, and I cannot escape blame by pointing a finger at the war. The blame was entirely mine.[9]

McCain urged his wife Carol to grant him a divorce, which she did in February 1980; the uncontested divorce took effect in April 1980.[4] The settlement included two houses, and financial support for ongoing medical treatments due to her 1969 car accident. They remained on good terms.[10]

In 1979, McCain met Cindy Lou Hensley, a teacher from Phoenix, Arizona.[10] McCain and Hensley were married on May 17, 1980, with Senators William Cohen and Gary Hart attending as groomsmen.[10] McCain's children did not attend, and several years would pass before they reconciled.[11]

In 1984, McCain and Cindy had their first child together, daughter Meghan, followed two years later by son John Sidney (Jack) IV, and in 1988 by son James (Jimmy). In 1991, Cindy McCain brought an abandoned three-month-old girl needing medical treatment to the U.S. from a Bangladeshi orphanage run by Mother Teresa.[4] The McCains decided to adopt her and named her Bridget.

McCain retired from the Navy as a captain in 1981 and moved to Arizona, where he entered politics. In 1982, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives, where he served two terms. He entered the U.S. Senate in 1987 and easily won reelection five times, the last time in 2016.

McCain entered the race for the Republican nomination for President in 2000, but lost a heated primary season contest to Governor George W. Bush of Texas. He secured the nomination in 2008, but was defeated by Democratic nominee Barack Obama in the general election.

In August 1999, McCain's memoir Faith of My Fathers, co-authored with Mark Salter, was published.[12] The most successful of his writings, it received positive reviews, became a bestseller, and was later made into a TV film.[13] The book traces McCain's family background and childhood, covers his time at Annapolis and his service before and during the Vietnam War, concluding with his release from captivity in 1973. According to one reviewer, it describes "the kind of challenges that most of us can barely imagine. It's a fascinating history of a remarkable military family."[14]

McCain underwent a minimally invasive craniotomy at Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, Arizona, on July 14, 2017, in order to remove a blood clot above his left eye. His absence prompted Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to delay a vote on the Better Care Reconciliation Act.[15] Five days later, Mayo Clinic doctors announced that the laboratory results from the surgery confirmed the presence of a glioblastoma, which is a very aggressive brain tumor.[16] Standard treatment options for this tumor include chemotherapy and radiation. Average survival time is approximately 14 months. McCain was a survivor of previous cancers, having had several melanomas removed.[16]

President Trump made a public statement wishing Senator McCain well, as did many others, including President Obama. On July 24, McCain announced that he would return to the United States Senate the following day.[17] In December 2017 he returned to Arizona to undergo treatment.

McCain's family announced on August 24, 2018, that he would no longer receive treatment for his cancer.[18] The next day on August 25, John McCain died with his wife and family beside him at his home in Cornville, Arizona, four days before his 82nd birthday.[19]

A quarter peal of Grandsire Caters in memory of McCain was rung by the bellringers of Washington National Cathedral the day following his death. Another memorial quarter peal was rung on September 6th on the Bells of Congress at the Old Post Office in Washington DC. Many governors, both Democratic and Republican, ordered flags in their states to fly at half-staff until interment.[20]

Prior to his death, McCain requested that former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama eulogize him at his funeral, and asked that President Donald Trump not attend.[21] President Trump issued a statement on August 27 praising McCain's service to the country, and signed a proclamation ordering flags around Washington DC to be flown at half-staff until McCain's interment.[22]

McCain lay in state in the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on August 29 (McCain's birthday), followed by a service at North Phoenix Baptist Church on August 30. His body traveled to Washington DC to lie in state in the rotunda of the United States Capitol on August 31, before a service at the Washington National Cathedral on September 1,[23] followed by burial at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery in Annapolis, Maryland, next to his Naval Academy classmate Admiral Charles R. Larson.[24]

McCain began his early military career when he was commissioned as an ensign and started two and a half years of training at Pensacola to become a naval aviator. He completed flight school in 1960 and became a naval pilot of ground-attack aircraft; he was assigned to A-1 Skyraider squadrons aboard the aircraft carriers USS Intrepid and USS Enterprise[8] in the Caribbean and Mediterranean Seas.[1]

His combat duty began when he was 30 years old in mid-1967, when USS Forrestal was assigned to a bombing campaign, Operation Rolling Thunder, during the Vietnam War.[12] On July 29, 1967, McCain was a lieutenant commander when he was near the epicenter of the USS Forrestal fire. He escaped from his burning jet and was trying to help another pilot escape when a bomb exploded;[25] McCain was struck in the legs and chest by fragments.[1] The ensuing fire killed 134 sailors and took 24 hours to control.[12] With the Forrestal out of commission, McCain volunteered for assignment with the USS Oriskany, another aircraft carrier employed in Operation Rolling Thunder.[1] Once there, he would be awarded the Navy Commendation Medal and the Bronze Star Medal for missions flown over North Vietnam.[26]

Prisoner of war

McCain was captured on October 26, 1967. He was flying his 23rd bombing mission over North Vietnam when his A-4E Skyhawk was shot down by a missile over Hanoi.[27][28] McCain fractured both arms and a leg when he ejected from the aircraft,[29] and nearly drowned after he parachuted into Trúc Bạch Lake. Some North Vietnamese pulled him ashore, then others crushed his shoulder with a rifle butt and bayoneted him.[27] McCain was then transported to Hanoi's main Hỏa Lò Prison, nicknamed the "Hanoi Hilton."[28]

Although McCain was seriously wounded and injured, his captors refused to treat him. They beat and interrogated him to get information, and he was given medical care only when the North Vietnamese discovered that his father was an admiral.[28] His status as a prisoner of war (POW) made the front pages of major newspapers.[30]

McCain spent six weeks in the hospital, where he received marginal care. In December 1967, McCain was placed in a cell with two other Americans who did not expect him to live more than a week.[4] In March 1968, McCain was placed into solitary confinement, where he would remain for two years.

In mid-1968, his father John S. McCain Jr. was named commander of all U.S. forces in the Vietnam theater, and the North Vietnamese offered McCain early release because they wanted to appear merciful for propaganda purposes and also to show other POWs that elite prisoners were willing to be treated preferentially.[28] McCain refused repatriation unless every man taken in before him was also released. Such early release was prohibited by the military Code of Conduct; to prevent the enemy from using prisoners for propaganda, officers were to be released in the order in which they were captured.[27]

Beginning in August 1968, McCain was subjected to a program of severe torture.[28] He was bound and beaten every two hours; this punishment occurred at the same time that he was suffering from dysentery. Eventually, McCain made an anti-U.S. propaganda "confession."[27] He always felt that his statement was dishonorable, but as he later wrote, "I had learned what we all learned over there: every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine."[1][31] McCain received two to three beatings weekly because of his continued refusal to sign additional statements.[4]

McCain was a prisoner of war in North Vietnam for five and a half years until his release on March 14, 1973.[32] His wartime injuries left him permanently incapable of raising his arms above his head.[33] After his release from the Hanoi Hilton, McCain returned to the site with his wife Cindy and family on a few occasions to come to grips with what happened to him there during his capture.[34]

Commanding officer, liaison to Senate

McCain underwent treatment for his injuries that included months of grueling physical therapy.[11] He attended the National War College at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C. during 1973–1974.[4] McCain was rehabilitated by late 1974 and his flight status was reinstated. In 1976, he became commanding officer of a training squadron that was stationed in Florida. He improved the unit's flight readiness and safety records,[35] and won the squadron its first-ever Meritorious Unit Commendation.

McCain served as the Navy's liaison to the U.S. Senate beginning in 1977.[36] In retrospect, he said that this represented his "real entry into the world of politics and the beginning of my second career as a public servant."[9] His key behind-the-scenes role gained congressional financing for a new supercarrier against the wishes of the Carter administration.[11][1]

McCain retired from the Navy on April 1, 1981,[4] as a captain.[26] He was designated as disabled and awarded a disability pension.[37] Upon leaving the military, he moved to Arizona. His numerous military decorations and awards include the Silver Star, two Legion of Merits, Distinguished Flying Cross, three Bronze Star Medals, two Purple Hearts, two Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medals, and Prisoner of War Medal.[26]

Political Career

U.S. Congressman

McCain set his sights on becoming a congressman because he was interested in current events, was ready for a new challenge, and had developed political ambitions during his time as Senate liaison.[1] In Phoenix he went to work for Hensley & Co., his new father-in-law Jim Hensley's large Anheuser-Busch beer distributorship.[10] As vice president of public relations at the distributorship, he gained political support among the local business community, meeting powerful figures such as banker Charles Keating Jr., real estate developer Fife Symington III (later Governor of Arizona), and newspaper publisher Darrow "Duke" Tully.[36]

In 1982, McCain ran as a Republican for an open seat in Arizona's 1st congressional district, which was being vacated by 30-year incumbent Republican John Jacob Rhodes. A newcomer to the state, McCain was hit with charges of being a carpetbagger. McCain responded to a voter making that charge with what a Phoenix Gazette columnist would later describe as "the most devastating response to a potentially troublesome political issue I've ever heard":[1]

Listen, pal. I spent 22 years in the Navy. My father was in the Navy. My grandfather was in the Navy. We in the military service tend to move a lot. We have to live in all parts of the country, all parts of the world. I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and living and spending my entire life in a nice place like the First District of Arizona, but I was doing other things. As a matter of fact, when I think about it now, the place I lived longest in my life was Hanoi.[10]

McCain won a highly contested primary election with the assistance of local political endorsements, his Washington connections, and money that his wife lent to his campaign. He then easily won the general election in the heavily Republican district.

In 1983, McCain was elected to lead the incoming group of Republican representatives, and was assigned to the House Committee on Interior Affairs. At this point, McCain's politics were mainly in line with President Ronald Reagan, which included support for Reaganomics, and he was active on Indian Affairs bills. He supported most aspects of the foreign policy of the Reagan administration, including its hardline stance against the Soviet Union and policy towards Central American conflicts, such as backing the Contras in Nicaragua. [4]

McCain won re-election to the House easily in 1984, and gained a spot on the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

U.S. Senator

McCain served as a United States Senator from Arizona from 1987 until his death in 2018, winning re-election five times.

First two terms in U.S. Senate

McCain's Senate career began in January 1987, after he defeated his Democratic opponent, former state legislator Richard Kimball.[36] He succeeded longtime American conservative icon and Arizona fixture Barry Goldwater upon the latter's retirement as U.S. senator from Arizona.[38]

Senator McCain became a member of the Armed Services Committee, with which he had formerly done his Navy liaison work; he also joined the Commerce Committee and the Indian Affairs Committee. He continued to support the Native American agenda.[39] As first a House member and then a senator—and as a lifelong gambler with close ties to the gambling industry[40]—McCain was one of the main authors of the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act,[41] which codified rules regarding Native American gambling enterprises.[42]

McCain soon gained national visibility. He delivered a well-received speech at the 1988 Republican National Convention, was mentioned by the press as a short list vice-presidential running mate for Republican nominee George H. W. Bush, and was named chairman of Veterans for Bush.[38]

McCain developed a reputation for independence during the 1990s. He took pride in challenging party leadership and establishment forces, becoming difficult to categorize politically. The term "maverick Republican" became a label frequently applied to McCain, and he also used it himself.[39]

As a member of the 1991–1993 Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, chaired by fellow Vietnam War veteran and Democrat, John Kerry, McCain investigated the Vietnam War POW/MIA issue to determine the fate of U.S. service personnel listed as missing in action during the Vietnam War. The committee's unanimous report stated there was "no compelling evidence that proves that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia."[43] Helped by McCain's efforts, in 1995 the U.S. normalized diplomatic relations with Vietnam.[44] McCain was vilified by some POW/MIA activists who, despite the committee's unanimous report, believed large numbers of Americans were still held against their will in Southeast Asia.[45]

In the 1996 presidential election, McCain was again on the short list of possible vice-presidential picks, this time for Republican nominee Bob Dole. The following year, Time magazine named McCain as one of the "25 Most Influential People in America."[46]

In 1997, McCain became chairman of the powerful Senate Commerce Committee. He took on the tobacco industry in 1998, proposing legislation that would increase cigarette taxes in order to fund anti-smoking campaigns, discourage teenage smokers, increase money for health research studies, and help states pay for smoking-related health care costs. Supported by the Clinton administration but opposed by the industry and most Republicans, the bill failed to gain cloture.[4]

Third Senate term

In November 1998, McCain won re-election to a third Senate term; he prevailed in a landslide over his Democratic opponent, environmental lawyer Ed Ranger.[47] In the February 1999 Senate trial following the impeachment of Bill Clinton, McCain voted to convict the president on both the perjury and obstruction of justice counts, saying Clinton had violated his sworn oath of office.[1]

Following his failure to win the Republican Presidential nomination, McCain began 2001 by breaking with the new George W. Bush administration on a number of matters, including HMO reform, climate change, and gun legislation. In May 2001, McCain was one of only two Senate Republicans to vote against the Bush tax cuts.[48] McCain used political capital gained from his presidential run, as well as improved legislative skills and relationships with other members, to become one of the Senate's most influential members.

After the September 11, 2001, attacks, McCain supported Bush and the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan.[48] He and Democratic senator Joe Lieberman wrote the legislation that created the 9/11 Commission,[49] while he and Democratic senator Fritz Hollings co-sponsored the Aviation and Transportation Security Act that federalized airport security.[50]

In March 2002, McCain–Feingold, officially known as the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, passed in both Houses of Congress and was signed into law by President Bush. Seven years in the making, it was McCain's greatest legislative achievement.[48]

Meanwhile, in discussions over proposed U.S. action against Iraq, McCain was a strong supporter of the Bush administration's position. stating that Iraq was "a clear and present danger to the United States of America," and voted accordingly for the Iraq War Resolution in October 2002.[48] He predicted that U.S. forces would be treated as liberators by a large number of the Iraqi people.[51]

In the 2004 U.S. presidential election campaign, McCain was once again frequently mentioned for the vice-presidential slot, only this time as part of the Democratic ticket under nominee John Kerry.[52] McCain said that while he and Kerry were close friends, Kerry had never formally offered him the position and that he would not have accepted it if he had.[53] At the 2004 Republican National Convention, McCain supported Bush for re-election, praising Bush's management of the War on Terror since the September 11 attacks.[54] At the same time, he defended Kerry's Vietnam War record.[55]

Fourth Senate term

In May 2005, McCain led the so-called Gang of 14 in the Senate, which established a compromise that preserved the ability of senators to filibuster judicial nominees, but only in "extraordinary circumstances."[56] The compromise took the steam out of the filibuster movement, but some Republicans remained disappointed that the compromise did not eliminate filibusters of judicial nominees in all circumstances.[57] McCain subsequently cast Supreme Court confirmation votes in favor of John Roberts and Samuel Alito, calling them "two of the finest justices ever appointed to the United States Supreme Court."[58]

By the middle of the 2000s (decade), the increased Indian gaming that McCain had helped bring about was a multi-billion dollar industry. He was twice chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, in 1995–1997 and 2005–2007, and his Committee helped expose the Jack Abramoff Indian lobbying scandal.[59] By 2005 and 2006, McCain was pushing for amendments to the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act that would limit creation of off-reservation casinos, as well as limiting the movement of tribes across state lines to build casinos.[60]

Owing to his time as a POW, McCain was recognized for his sensitivity to the detention and interrogation of detainees in the War on Terror. An opponent of the Bush administration's use of torture and detention without trial at Guantánamo Bay (declaring that "even Adolf Eichmann got a trial"[61]), in October 2005, McCain introduced the McCain Detainee Amendment prohibiting inhumane treatment of prisoners to the Defense Appropriations bill for 2005. Although Bush had threatened to veto the bill if McCain's amendment was included, the President announced in December 2005 that he accepted McCain's terms and would "make it clear to the world that this government does not torture and that we adhere to the international convention of torture, whether it be here at home or abroad".[62] This stance, among others, led to McCain being named by Time magazine in 2006 as one of America's 10 Best Senators.[63]

Following his defeat in the presidential election in 2008, McCain returned to the Senate amid varying views about what role he might play there. In mid-November 2008 he met with President-elect Obama, and the two discussed issues they had commonality on.[64] As the inauguration neared, Obama consulted with McCain on a variety of matters, to an extent rarely seen between a president-elect and his defeated rival.[65]

Nevertheless, McCain emerged as a leader of the Republican opposition to the Obama economic stimulus package of 2009, saying it had too much spending for too little stimulative effect.[66] McCain also voted against Obama's Supreme Court nomination of Sonia Sotomayor and by August 2009 was siding more often with his Republican Party on closely divided votes than ever before in his senatorial career.

When the health care plan, now called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, passed Congress and became law in March 2010, McCain strongly opposed the landmark legislation not only on its merits but also on the way it had been handled in Congress. As a consequence, he warned that congressional Republicans would not be working with Democrats on anything else: "There will be no cooperation for the rest of the year. They have poisoned the well in what they've done and how they've done it."[67]

Fifth Senate term

As the Arab Spring took center stage in late 2010, McCain urged that the embattled Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, step down and thought the U.S. should push for democratic reforms in the region despite the associated risks of religious extremists gaining power.

He became one of the most vocal critics of the Obama administration's handling of the September 11, 2012, attack on the U.S. diplomatic mission in Benghazi, saying it was a "debacle" that featured either "a massive cover-up or incompetence that is not acceptable" and that it was worse than the Watergate scandal.[68] As part of this, he and a few other senators were successful in blocking the planned nomination of Ambassador to the UN Susan Rice to succeed Hillary Rodham Clinton as U.S. Secretary of State; McCain's friend and colleague John Kerry was nominated instead.

During 2013, McCain was a member of a bi-partisan group of senators, the "Gang of Eight," which announced principles for another try at comprehensive immigration reform.[69] This and other negotiations showed that McCain had improved relations with the Obama administration, including the president himself, as well as with Democratic Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, and that he had become the leader of a power center in the Senate for cutting deals in an otherwise bitterly partisan environment. They also led some observers to conclude that the "maverick" McCain had returned.[70]

McCain remained stridently opposed to many aspects of Obama's foreign policy, and in June 2014, following major gains by the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant in the 2014 Northern Iraq offensive, decried what he saw as a U.S. failure to protect its past gains in Iraq and called on the president's entire national security team to resign. McCain said, "Could all this have been avoided? ... The answer is absolutely yes. If I sound angry it's because I am angry."[71]

In January 2015, McCain became chair of the Armed Services Committee, a longtime goal of his. In this position, he led the writing of proposed Senate legislation that sought to modify parts of the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986 in order to return responsibility for major weapons systems acquisition back to the individual armed services and their secretaries and away from the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics.[72] As chair, McCain tried to maintain a bipartisan approach and forged a good relationship with ranking member Jack Reed.[73]

During the 2016 Republican primaries, McCain said he would support the Republican nominee even if it was Donald Trump, but following Mitt Romney's March 3 speech, McCain endorsed the sentiments expressed in that speech, saying he had serious concerns about Trump's "uninformed and indeed dangerous statements on national security issues".[74] Following Trump becoming the presumptive nominee of the party on May 3, McCain said that Republican voters had spoken and he would support Trump.[75] However, on October 8, McCain withdrew his endorsement of Trump.[76] McCain stated that Trump's "demeaning comments about women and his boasts about sexual assaults" made it "impossible to continue to offer even conditional support" and added that he would not vote for Hillary Clinton, but would instead "write in the name of some good conservative Republican who is qualified to be president."[77]

Sixth and final Senate term

McCain chaired the January 5, 2017, hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee where Republican and Democratic senators and intelligence officers, including James R. Clapper Jr., the Director of National Intelligence, Michael S. Rogers, the head of the National Security Agency and United States Cyber Command presented a "united front" that "forcefully reaffirmed the conclusion that the Russian government used hacking and leaks to try to influence the presidential election."[78]

Repeal and replacement of Obamacare (the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) had been a centerpiece of McCain's 2016 re-election campaign, and in July 2017 he said, "Have no doubt: Congress must replace Obamacare, which has hit Arizonans with some of the highest premium increases in the nation and left 14 of Arizona's 15 counties with only one provider option on the exchanges this year." He added that he supports affordable and quality health care, but objected that the pending Senate bill did not do enough to shield the Medicaid system in Arizona.[79]

McCain returned to the Senate on July 25, less than two weeks after brain surgery. He cast a deciding vote allowing the Senate to begin consideration of bills to replace Obamacare. Along with that vote, he delivered a speech criticizing the party-line voting process used by the Republicans, as well as by the Democrats in passing Obamacare to begin with, and McCain also urged a "return to regular order" utilizing the usual committee hearings and deliberations.[80] On July 28, he cast the deciding vote against a Republican health care bill that would have repealed Obamacare but not replaced it, which would have cost millions of people their health care.[81]

McCain did not vote in the Senate after December 2017, remaining instead in Arizona to undergo cancer treatment.

Presidential campaigns

McCain entered the race for the Republican nomination for President in 2000, but lost a heated primary season contest to Governor George W. Bush. He was the Republican nominee for President of the United States in the 2008 election, which he lost to Barack Obama.

2000 presidential campaign

McCain announced his candidacy for president on September 27, 1999, in Nashua, New Hampshire, saying he was staging "a fight to take our government back from the power brokers and special interests, and return it to the people and the noble cause of freedom it was created to serve."[82] Texas Governor George W. Bush, who had the political and financial support of most of the party establishment, was the frontrunner for the Republican nomination was.[83]

McCain began his campaign strongly, winning New Hampshire's primary with 49 percent of the vote to Bush's 30 percent. However, he then lost in South Carolina on February 19. McCain's campaign never completely recovered from his South Carolina defeat, and on March 7 he lost nine of the thirteen primaries on Super Tuesday to Bush.[84]

McCain withdrew from the race on March 9, 2000, and endorsed Bush two months later.[85]

2008 presidential campaign

McCain formally announced his intention to run for President of the United States on April 25, 2007 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He stated that "he was not running for the White House 'to be somebody' but to do his best for his country."[86]

McCain was born in the Panama Canal Zone. Had he been elected, he would have become the first president who was born outside the contiguous forty-eight states. This raised a potential legal issue, since the United States Constitution requires the president to be a natural-born citizen of the United States. A bipartisan legal review concluded that he is a natural-born citizen.[87] If inaugurated in 2009 at the age of 72 years and 144 days, he would have been the oldest U.S. president upon becoming president.[88]

McCain's health was an issue. In May 2008, McCain's campaign let the press review his medical records, and he was described as appearing cancer-free, having a strong heart, and in general being in good health.[89] He had been treated for a type of skin cancer called melanoma, and an operation in 2000 for that condition left a noticeable mark on the left side of his face. McCain's prognosis appeared favorable, according to independent experts, especially because he had already survived without a recurrence for more than seven years.[90]

McCain's oft-cited strengths as a presidential candidate for 2008 included national name recognition, sponsorship of major lobbying and campaign finance reform initiatives, his ability to reach across the aisle, his well-known military service and experience as a POW, his experience from the 2000 presidential campaign, and an expectation that he would capture Bush's top fundraisers.[91] During the 2006 election cycle, McCain had attended 346 events[33] and helped raise more than $10.5 million on behalf of Republican candidates. McCain also became more willing to ask business and industry for campaign contributions, while maintaining that such contributions would not affect any official decisions he would make.[92]

On February 5, McCain won both the majority of states and delegates in the Super Tuesday Republican primaries, giving him a commanding lead toward the Republican nomination. His wins in the March 4 primaries clinched a majority of the delegates, and he became the presumptive Republican nominee.[93]

McCain's focus shifted toward the general election, while Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton fought a prolonged battle for the Democratic nomination.[94]

On August 29, 2008, McCain revealed Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as his surprise choice for running mate.[95] McCain was only the second U.S. major-party presidential nominee (after Walter Mondale) to select a woman for his running mate and the first Republican to do so; Palin would have become the first female Vice President of the United States if McCain had been elected. On September 3, 2008, McCain and Palin became the Republican Party's presidential and vice presidential nominees, respectively, at the 2008 Republican National Convention in Saint Paul, Minnesota. McCain surged ahead of Obama in national polls following the convention, as the Palin pick energized core Republican voters who had previously been wary of him.[96] However, by the campaign's own later admission, the rollout of Palin to the national media went poorly,[97] and voter reactions to Palin grew increasingly negative, especially among independents and other voters concerned about her qualifications.[98] McCain said later in life that he expressed regret for not choosing the independent Senator Joe Lieberman as his VP candidate instead.[61]

On September 24, McCain said he was temporarily suspending his campaign activities, called on Obama to join him, and proposed delaying the first of the general election debates with Obama, in order to work on the proposed U.S. financial system bailout before Congress, which was targeted at addressing the subprime mortgage crisis and liquidity crisis.[99] McCain's intervention helped to give dissatisfied House Republicans an opportunity to propose changes to the plan that was otherwise close to agreement.[100][101] On October 1, McCain voted in favor of a revised $700 billion rescue plan.

The election took place on November 4, and Barack Obama was projected the winner at about 11:00 pm Eastern Standard Time; McCain delivered his concession speech in Phoenix, Arizona about twenty minutes later. In it, he noted the historic and special significance of Obama becoming the nation's first African American president.[102]

Public image

McCain's personal character was a dominant feature of his public image.[103] This image includes the military service of both himself and his family, the circumstances and tensions surrounding the end of his first marriage and beginning of second, his maverick political persona, his temper, his admitted problem of occasional ill-considered remarks, and his close ties to his children from both his marriages. His family's military tradition extends to the latest generation: son John Sidney IV ("Jack") graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 2009, becoming the fourth generation John S. McCain to do so, and is a helicopter pilot; son James served two tours with the Marines in the Iraq War; and son Doug flew jets in the navy.[104]

McCain's political appeal was more nonpartisan and less ideological compared to many other national politicians. His stature and reputation stemmed partly from his service in the Vietnam War: "The hero is indispensable to the McCain persona."[105] He also carried physical vestiges of his war wounds, as well as his melanoma surgery.

Writers often extolled McCain for his courage not just in war but in politics, and wrote sympathetically about him.[33][103][105] McCain's shift of political stances and attitudes during and especially after the 2008 presidential campaign, including his self-repudiation of the maverick label, left writers expressing sadness and wondering what had happened to the McCain they thought they had known.[106] By 2013, some aspects of the older McCain had returned, and his image became that of a kaleidoscope of contradictory tendencies, including, as one writer listed, "the maverick, the former maverick, the curmudgeon, the bridge builder, the war hero bent on transcending the call of self-interest to serve a cause greater than himself, the sore loser, old bull, last lion, loose cannon, happy warrior, elder statesman, lion in winter...."[107]

In his own estimation, the Arizona senator was straightforward and direct, but impatient: "God has given me heart enough for my ambitions, but too little forbearance to pursue them by routes other than a straight line."[9] McCain did not shy away from addressing his shortcomings, and apologizing for them.[38] He was known for sometimes being prickly and hot-tempered with Senate colleagues, but his relations with his own Senate staff were more cordial, and inspired loyalty towards him.[108] He formed a strong bond with two senators, Joe Lieberman and Lindsey Graham, over hawkish foreign policy and overseas travel, and they became dubbed the "Three Amigos."[109]

Legacy

McCain received many tributes and condolences, including from Congressional colleagues, all living former Presidents – Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama – and former Vice President Joe Biden, as well as Vice President Mike Pence and President Richard Nixon's daughters Tricia Nixon Cox and Julie Nixon Eisenhower.[110] French President Emmanuel Macron, Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who had just taken office the previous day, and former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, British Prime Minister Theresa May and former Prime Minister David Cameron, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and former Prime Minister Stephen Harper, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and foreign minister Heiko Maas, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Afghanistan chief executive Abdullah Abdullah, Pakistani foreign minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi, and former Vietnamese ambassador to Washington Nguyễn Quốc Cường also sent condolences.[111]

Colonel Trần Trọng Duyệt, who ran the Hỏa Lò Prison when McCain was held there, remarked,

At that time I liked him personally for his toughness and strong stance. Later on, when he became a US Senator, he and Senator John Kerry greatly contributed to promote [Vietnam]-US relations so I was very fond of him. When I learnt about his death early this morning, I feel very sad. I would like to send condolences to his family.[112]

In a TV interview, Senator Lindsey Graham said McCain's last words to him were "I love you, I have not been cheated."[113] His daughter, Meghan McCain, shared her grief, stating that she was present at the moment he died.[114]

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) announced that he would introduce a resolution to rename the Russell Senate Office Building after McCain.[115]

Awards and honors

In addition to his military honors and decorations, McCain was granted a number of civilian awards and honors.

In 1997, Time magazine named McCain as one of the "25 Most Influential People in America."[46] In 1999, McCain shared the Profile in Courage Award with Senator Russ Feingold for their work towards campaign finance reform. The following year, the same pair shared the Paul H. Douglas Award for Ethics in Government.[116]

In 2005, The Eisenhower Institute awarded McCain the Eisenhower Leadership Prize.[117] This prize recognizes individuals whose lifetime accomplishments reflect Dwight D. Eisenhower's legacy of integrity and leadership. In 2006, the Bruce F. Vento Public Service Award was bestowed upon McCain by the National Park Trust.[118] The same year, McCain was awarded the Henry M. Jackson Distinguished Service Award by the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs, in honor of Senator Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson.[119] In 2007, the World Leadership Forum presented McCain with the Policymaker of the Year Award; it is given internationally to someone who has "created, inspired or strongly influenced important policy or legislation."[120]

In 2010, President Mikheil Saakashvili of Georgia awarded McCain the Order of National Hero, an award never previously given to a non-Georgian.[121] In 2015, the Kiev Patriarchate awarded McCain its own version of the Order of St. Vladimir.[122] In 2016, Allegheny College awarded McCain, along with Vice President Joe Biden, its Prize for Civility in Public Life.[123] McCain also received the Liberty Medal from the National Constitution Center in 2017.[124]

McCain received several honorary degrees from colleges and universities in the United States and internationally. These include Colgate University (LL.D 2000),[125] The Citadel (DPA 2002),[126] Wake Forest University (LL.D May 20, 2002),[127] the University of Southern California (DHL May 2004),[128] Northwestern University (LL.D June 17, 2005),[129] Liberty University (2006),[130] and the Royal Military College of Canada (D.MSc June 27, 2013).[131] He was also made an Honorary Patron of the University Philosophical Society at Trinity College Dublin in 2005.

Selected Works

- Faith of My Fathers by John McCain, Mark Salter (Random House, August 1999) ISBN 0375501916 (later made into the 2005 television film Faith of My Fathers)

- Worth the Fighting For by John McCain, Mark Salter (Random House, September 2002) ISBN 0375505423

- Why Courage Matters: The Way to a Braver Life by John McCain, Mark Salter (Random House, April 2004) ISBN 1400060303

- Character Is Destiny: Inspiring Stories Every Young Person Should Know and Every Adult Should Remember by John McCain, Mark Salter (Random House, October 2005) ISBN 1400064120

- Hard Call: Great Decisions and the Extraordinary People Who Made Them by John McCain, Mark Salter (Hachette, August 2007) ISBN 0446580406

- Thirteen Soldiers: A Personal History of Americans at War by John McCain, Mark Salter (Simon & Schuster, November 2014) ISBN 1476759650

- The Restless Wave: Good Times, Just Causes, Great Fights, and Other Appreciations by John McCain, Mark Salter (Simon & Schuster, May 2018) ISBN 978-1501178009

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Robert Timberg John McCain, An American Odyssey (Simon and Schuster, 1999, ISBN 068486794X).

- ↑ Samuel Eliot Morison, The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (Little, Brown and Company, 1963, ISBN 978-0196472508).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Paul Alexander, Man of the People: The Life of John McCain (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2002, ISBN 047122829X).

- ↑ Bruce Smith, McCain Says He's Been Baptist for Years The Washington Post, September 16, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Robert Timberg, The Nightingale's Song (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996, ISBN 0684803011)

- ↑ Can McCain Box His Way to the Nomination? Newsweek, May 13, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Barbara Silberdick Feinberg, John McCain: Serving His Country (Brookfield, CT: Millbrook Press, 2000, ISBN 0761319743).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 John McCain and Mark Salter, Worth the Fighting For (New York: Random House, 2002, ISBN 978-0375505423).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Dan Nowicki and Bill Muller, "John McCain Report: Arizona, the early years", The Arizona Republic, March 1, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Nicholas Kristof, P.O.W. to Power Broker, A Chapter Most Telling The New York Times, February 27, 2000. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 John McCain and Mark Salter, Faith of My Fathers (New York: Random House, 1999, ISBN 0375501916).

- ↑ Jeffrey Ressner and Kenneth Vogel, McCain’s TV biopic, reconsidered The Politico, July 3, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2018.}

- ↑ Brad Knickerbocker, "From a Vietnam Prison to the United States Senate", The Christian Science Monitor, September 16, 1999. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ Phil Mattingly, Manu Raju, and Steve Almasy, McConnell delays health care vote while McCain recovers from surgery CNN, July 17, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Susan Scutti, Sen. John McCain had aggressive brain tumor surgically removed CNN, July 20, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ↑ Sean Sullivan, Kelsey Snell, Ed O'Keefe, and John Wagner, McCain's return to Senate injects momentum into GOP health-care battle The Washington Post, July 24, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ↑ Nicholas Fandos and Jonathan Martin, John McCain Will No Longer Be Treated for Brain Cancer, Family Says The New York Times, August 24, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ↑ Elizabeth Chuck, Sen. John McCain, independent voice of the GOP establishment, dies at 81 NBC News, August 25, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ↑ John Verhovek, Unlike White House, some governors order flags at half-staff through McCain's burial ABC News, August 27, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ McCain requested Obama and George W. Bush deliver eulogies at funeral CBS News, August 27, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Ken Meyer, Trump Issues Statement on McCain After Silence Met With Criticism: ‘I Respect’ His Service MediaIte, August 27, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ Julie Hirschfeld Davis, Carl Hulse, and Emily Cochrane, Congress Honors One of Its Own: John McCain Lies in State in U.S. Capitol The New York Times, August 31, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ↑ Senator McCain to be Laid to Rest at the U.S. Naval Academy Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ↑ Bernard Weinraub, "Start of Tragedy: Pilot Hears a Blast As He Checks Plane", The New York Times, July 31, 1967. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Jim Kuhnhenn, "Navy releases McCain's military record". The Boston Globe, May 7, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Dan Nowicki and Bill Muller, "John McCain Report: Prisoner of War", The Arizona Republic, March 1, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 John G. Hubbell, P.O.W.: A Definitive History of the American Prisoner-Of-War Experience in Vietnam, 1964–1973 (New York: Reader's Digest Press, 1976, ISBN 0883490919).

- ↑ Michael Dobbs, "In Ordeal as Captive, Character Was Shaped", The Washington Post, October 5, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ R. W. Apple, Jr., "Adm. McCain's son, Forrestal Survivor, Is Missing in Raid", The New York Times, October 28, 1967. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ John McCain, John McCain, Prisoner of War: A First-Person Account U.S. News & World Report, January 28, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ James Sterba, "P.O.W. Commander Among 108 Freed", The New York Times, March 15, 1973. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Todd S. Purdum, Prisoner of Conscience Vanity Fair, February 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ Mark Landler, McCain, in Vietnam, Finds the Past isn't Really the Past The New York Times, April 27, 2000. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ Ralph Vartabedian, McCain has long relied on his grit Los Angeles Times, April 14, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Douglas Frantz, The 2000 Campaign: The Arizona Ties; A Beer Baron and a Powerful Publisher Put McCain on a Political Path The New York Times, February 21, 2000. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ Ralph Vartabedian, McCain's disability pension may renew questions about his fitness, Los Angeles Times, April 22, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Dan Nowicki and Bill Muller, John McCain Report: The Senate calls The Arizona Republic, March 1, 2007. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Michael Barone and Grant Ujifusa, The Almanac of American Politics 2000 (Three Rivers Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0812931945).

- ↑ Jo Becker and Don Van Natta Jr., For McCain and Team, a Host of Ties to Gambling The New York Times, September 27, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Tadd Johnson, Regulatory Issues and Impacts of Gaming in Indian Country, Increasing Understanding of Public Problems and Policies: Proceedings of the 1998 National Public Policy Education Conference, 140–144. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ W. Dale Mason, Indian Gaming: Tribal Sovereignty and American Politics (University of Oklahoma Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0806132600).

- ↑ Report of the Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, U.S. Senate, January 13, 1993. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ James Walsh, Good Morning, Vietnam Time, July 24, 1995. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ John Aloysius Farrell, At the center of power, seeking the summit The Boston Globe, June 21, 2003. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Bio: Sen. John McCain Fox News, April 13, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Dan Nowicki and Bill Muller, McCain Profile: McCain becomes the 'maverick' The Arizona Republic, March 1, 2007. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 Dan Nowicki and Bill Muller, John McCain Report: The 'maverick' and President Bush The Arizona Republic, March 1, 2007. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Senate bill would implement 9/11 panel proposals CNN, September 8, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Senate Approves Aviation Security, Anti-Terrorism Bills, PBS Online NewsHour, October 12, 2001. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Sen. McCain's Interview With Chris Matthews, Hardball with Chris Matthews, MSNBC, March 12, 2003. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ The Associated Press, Campaign 2004 USA Today, March 10, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Dan Balz and Jim VandeHei, McCain's Resistance Doesn't Stop Talk of Kerry Dream Ticket The Washington Post, June 12, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Sean Loughlin, McCain praises Bush as 'tested' CNN, August 30, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Zachary Coile, Vets group attacks Kerry; McCain defends Democrat San Francisco Chronicle, August 6, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Senators compromise on filibusters; Bipartisan group agrees to vote to end debate on 3 nominees, CNN, May 24, 2005. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Carl Hulse, Distrust of McCain Lingers Over '05 Deal on Judges The New York Times, February 25, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Tom Curry, McCain takes grim message to South Carolina NBCNews, April 26, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Susan Schmidt and James V. Grimaldi, Panel Says Abramoff Laundered Tribal Funds; McCain Cites Possible Fraud by Lobbyist, The Washington Post, June 23, 2005. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Fox Butterfield, Indians' Wish List: Big-City Sites for Casinos, The New York Times, April 8, 2005. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 John McCain obituary The Sunday Times, August 26, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ McCain, Bush agree on torture ban, CNN, December 15, 2005. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Perry Bacon Jr. and Massimo Calabresi, America's 10 Best Senators, Time, April 16, 2006. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Jake Tapper, Obama, McCain Meet While Bill Speaks About Hillary, ABC News, November 17, 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ David D. Kirkpatrick, Obama Reaches Out for McCain's Counsel, The New York Times, January 19, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Carl Hulse and David M. Herszenhorn, Senators Reach Deal on Stimulus Plan as Jobs Vanish, The New York Times, February 6, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Michael O'Brien, McCain: Don't expect GOP cooperation on legislation for the rest of this year, The Hill, March 22, 2010. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ David Eldridge, McCain slams Obama on Libya: 'Nobody died in Watergate', The Washington Times, October 28, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Emily Deruy, Gang of Eight Accelerates Immigration Reform Pace, ABC News, January 30, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ Albert R. Hunt, McCain's a maverick again, Miami Herald, July 30, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ Kevin Baron, McCain Calls for Obama's National Security Team to Resign Over Iraq, National Journal, June 12, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ McCain Would Let Services Out of 'Penalty Box', Defense News, May 22, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ Jennifer Steinhauer, With Chairmanship, McCain Seizes Chance to Reshape Pentagon Agenda, The New York Times, June 9, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ Gintautas Dumcius, Sen. John McCain backs up Mitt Romney, says Donald Trump's comments 'uninformed and indeed dangerous', The Republican, March 3, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ Manu Raju, Flake, McCain split over backing Trump, CNN, May 5, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ Burgess Everett, How McCain finally decided he couldn't stomach Trump anymore, Politico, October 8, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Sabrina Siddiqui, Ben Jacobs, and Edward Helmore, John McCain withdraws support for Donald Trump over groping boasts, The Guardian, October 8, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Matt Flegenheimer and Scott Shane, Countering Trump, Bipartisan Voices Strongly Affirm Findings on Russian Hacking The New York Times, January 5, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Dan Nowicki, McCain is not happy with the new Senate health bill. Here's what he wants, The Arizona Republic, July 14, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Richard Cowa and James Oliphant, In hero's return, McCain blasts Congress, tells senators to stand up to Trump Reuters, July 25, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Lauren Fox, John McCain's maverick moment CNN, July 28, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ McCain formally kicks off campaign, CNN, September 27, 1999. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Frank Bruni, Quayle, Outspent by Bush, Will Quit Race, Aide Says, The New York Times, September 27, 2000. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Ian Christopher McCaleb, Gore, Bush post impressive Super Tuesday victories, CNN, March 8, 2000. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Peter Marks, A Ringing Endorsement for Bush, The New York Times, May 14, 2000. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ McCain launches White House bid", BBC News, April 25, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Lawyers Conclude McCain Is "Natural Born", CBS News, March 28, 2008.

- ↑ Dana Bash, With McCain, 72 is the new... 69?, CNN, September 4, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Medical records show McCain is in good health. International Herald Tribune, May 23, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Lawrence K. Altman, On the Campaign Trail, Few Mentions of McCain's Bout With Melanoma, The New York Times, March 9, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Dan Balz, For Possible '08 Run, McCain Is Courting Bush Loyalists, The Washington Post, February 12, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Jeffrey H. Birnbaum and John Solomon, McCain's Unlikely Ties to K Street, The Washington Post, December 31, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Clinton wins key primaries, CNN projects; McCain clinches nod, CNN, March 4, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Susan Page, "McCain runs strong as Democrats battle on" ABC News, April 28, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ McCain taps Alaska Gov. Palin as vice president pick, CNN, August 29, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Russell Berman, McCain-Palin Surging in the Polls, The New York Sun, September 9, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Adam Nagourney, In Election's Wake, Campaigns Offer a Peek at What Really Happened, The New York Times, December 9, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Jon Cohen and Jennifer Agiesta, Perceptions of Palin Grow Increasingly Negative, Poll Says, The Washington Post, October 25, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ John McCain Statement: 'Suspending' His Campaign, [ABC News, September 24, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2018

- ↑ Jonathan Weisman, How McCain Stirred a Simmering Pot, The Washington Post, September 27, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 20108. "In truth, McCain's dramatic announcement Wednesday that he would suspend his campaign and come to Washington for the bailout talks had wide repercussions."

- ↑ Cheryl Gay Stolberg and Elisabeth Bumiller, A Balancing Act as McCain Faces a Divided Party and a Skeptical Public, The New York Times, September 26, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2018. "His greatest contribution," Mr. Bachus said, "was returning to Washington and standing up for Republicans who were refusing to be stampeded."

- ↑ Transcript: McCain concedes presidency, CNN, November 4, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2018

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 David Brooks, The Character Factor, The New York Times, November 13, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Sheryl Gay Stolberg, Obama Is Embraced at Annapolis, The New York Times, May 23, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Albert R. Hunt, "John McCain and Russell Feingold" in Caroline Kennedy (ed.), Profiles in Courage for Our Time (Hyperion, 2003, ISBN 978-0786886784).

- ↑ Todd S. Purdum, The Man Who Never Was, Vanity Fair, November 2010. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Mark Leibovich, How John McCain Turned His Clichés Into Meaning, The New York Times Magazine, December 18, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Elizabeth Drew, Citizen McCain (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002, ISBN 978-0743230025).

- ↑ Jennifer Steinhauer, Foreign Policy's Bipartisan Trio Becomes Republican Duo, The New York Times, November 26, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ↑ Mary Jo Pitzl, Six presidents, nation, world react to John McCain's death Arizona Republic, August 25, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Rick Noack, 'A great defender of liberty': World leaders mourn Sen. John McCain The Washington Post, August 26, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ US Senator McCain – who helps lay foundation for VN-US relations – passes away Việt Nam News, August 26, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Adam Edelman, Lindsey Graham reveals McCain's last words to him in tearful interview NBC News, August 28, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Jordan Runtagh, Meghan McCain Shares Touching Tribute to Late Father: 'All That I Am Is Thanks to Him' People, August 25, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Emily Tillett, Schumer proposes renaming Russell Senate Office Building for John McCain CBS News, August 26, 2018. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ↑ Russell Feingold & John McCain - 2000, Institute of Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Senator John S. McCain to Receive 2005 Eisenhower Leadership Prize, The Eisenhower Institute, August 24, 2005. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ National Park Trust Awards Senator John McCain Highest Honor National Park Trust, June 8, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ JINSA Bestows Distinguished Service Award Upon Senator John McCain Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs, December 5, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Malcolm Turner, Senator John McCain receives Policy Maker of the Year Award, World Leadership Forum, February 20, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Senator McCain Visits Batumi (January 10–11 U.S. Embassy to Georgia. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Leader of Ukrainian schismatics awards anti-Russian senator McCain, Interfax-Ukraine, February 5, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Tracie Mauriello, Allegheny College awards civility prize to Joe Biden and John McCain, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 8, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ McCain condemns isolationist politics, calls it 'unpatriotic' Fox News, October 17, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Honorary degree recipients, Colgate University, July 2000. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Citadel announces graduation awards", The Citadel, May 11, 2002. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Commencement News, Wake Forest University, June 2002. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Past Recipients, University of Southern California. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ McCain to Speak at Commencement, Eight to Receive Honorary Degrees, Northwestern University, June 7, 2005. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Jessica Vrazilek, John McCain: For Liberty at Liberty, CBS News, May 15, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ↑ Lee-Anne Goodman, Peter MacKay in U.S. meeting with Chuck Hagel, John McCain, CTV News, June 18, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexander, Paul. Man of the People: The Life of John McCain. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. ISBN 047122829X

- Barone, Michael, and Grant Ujifusa. The Almanac of American Politics 2000. Three Rivers Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0812931945

- Brock, David, and Paul Waldman. Free Ride: John McCain and the Media. New York: Anchor Books, 2008. ISBN 0307279405

- Drew, Elizabeth. Citizen McCain. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 978-0743230025

- Feinberg, Barbara Silberdick. John McCain: Serving His Country. Brookfield, CT: Millbrook Press, 2000. ISBN 0761319743

- Hubbell, John G. P.O.W.: A Definitive History of the American Prisoner-Of-War Experience in Vietnam, 1964–1973. New York: Reader's Digest Press, 1976. ISBN 0883490919

- Karaagac, John. John McCain: An Essay in Military and Political History. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2000. ISBN 0739101714

- Kennedy, Caroline (ed.). Profiles in Courage for Our Time. Hyperion, 2003. ISBN 978-0786886784)

- Mason, W. Dale. Indian Gaming: Tribal Sovereignty and American Politics. University of Oklahoma Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0806132600

- McCain, John and Mark Salter. Faith of My Fathers. New York: Random House, 1999. ISBN 0375501916

- McCain, John and Salter, Mark. Worth the Fighting For. New York: Random House, 2002. ISBN 978-0375505423

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War. Little, Brown and Company, 1963 ISBN 978-0196472508

- Rochester, Stuart I., and Frederick Kiley. Honor Bound: American Prisoners of War in Southeast Asia, 1961–1973. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1999. ISBN 1557506949

- Schecter, Cliff. The Real McCain: Why Conservatives Don't Trust Him and Why Independents Shouldn't. Sausalito, CA: PoliPoint Press, 2008. ISBN 0979482291

- Timberg, Robert. John McCain: An American Odyssey. New York: Touchstone Books, 1999. ISBN 068486794X

- Timberg, Robert. The Nightingale's Song. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. ISBN 0684803011

- Welch, Matt. McCain: The Myth of a Maverick. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. ISBN 0230603963

External links

All links retrieved August 3, 2022.

- John McCain official site

- John Sydney McCain, III Encyclopædia Britannica

- John Sydney McCain, III Biographical Directory of the United States Senate

- John Sydney McCain, III Find A Grave

- John McCain's American Story: As seen by Arizona journalists who know him best

| United States House of Representatives

Template:US House succession box | ||

|---|---|---|

| Party Political Offices | ||

| Preceded by: Barry Goldwater |

Republican nominee for U.S. Senator from Arizona (Class 3) 1986, 1992, 1998, 2004, 2010, 2016 |

Most recent |

| Preceded by: Susan Molinari |

Keynote Speaker of the Republican National Convention 2000 Served alongside: Colin Powell |

Succeeded by: Zell Miller |

| Preceded by: George W. Bush |

Republican nominee for President of the United States 2008 |

Succeeded by: Mitt Romney |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by: Barry Goldwater |

United States Senator (Class 3) from Arizona 1987–2018 Served alongside: Dennis DeConcini, Jon Kyl, Jeff Flake |

Vacant

|

| Preceded by: Daniel Inouye |

Chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee 1995–1997 |

Succeeded by: Ben Nighthorse Campbell |

| Preceded by: Larry Pressler |

Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee 1997–2001 |

Succeeded by: Fritz Hollings |

| Preceded by: Fritz Hollings |

Ranking Member of the Senate Commerce Committee 2001 | |

| Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee 2001 | ||

| Ranking Member of the Senate Commerce Committee 2001–2003 | ||

| Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee 2003–2005 |

Succeeded by: Ted Stevens | |

| Preceded by: Ben Nighthorse Campbell |

Chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee 2005–2007 |

Succeeded by: Byron Dorgan |

| Preceded by: Carl Levin |

Ranking Member of the Senate Armed Services Committee 2007–2013 |

Succeeded by: Jim Inhofe |

| Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee 2015–2018 |

Vacant

| |

| Honorary Titles | ||

| Preceded by: Billy Graham |

Persons who have lain in state or honor in the United States Capitol rotunda August 31, 2018 |

Most recent |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.