Islam in India

|

History |

| Architecture |

|

Mughal · Indo-Islamic |

| Major figures |

|

Moinuddin Chishti · Akbar |

| Communities |

|

Northern · Mappilas · Tamil |

| Islamic sects |

|

Barelvi · Deobandi · Shia |

| Culture |

|

Muslim culture of Hyderabad |

| Other topics |

|

Ahle Sunnat Movement in South Asia |

Islam in India constitutes the second-most practiced religion after Hinduism, with approximately 151 million Muslims in India's population as of 2007 (according to government census 2001), i.e., 13.4 percent of the population. Currently, India has the third largest population of Muslims in the world, after Indonesia and Pakistan.

Islam in India has had a fascinating, and powerful impact. Indeed, Islam has become woven into the very fabric of Indian civilization and culture. Muslims arrived in India during the life of Muhammad the Prophet, establishing mosques and organizing missionary endeavors in the seventh century C.E. Those missionary efforts proved successful, rooting Islam firmly into Indian life. As often happens with missionary movements from all religions, merchant and trade endeavors went hand in hand with missionary work. Arabs had had a presence in India before the birth of Muhammad. That probably facilitated making inroads for Islam, since Arab traders established in India who converted to Islam already had a base of operations established. in the phenomenally diverse religious and cultural landscape of India.

Islam in India had the unique experience of having to coexist with other religions. Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism all had their origins in India. Although Buddhism went into decline in India from the eighth century C.E., it still maintained a major presence. Islam had to accommodate itself to one degree or another with most of the major world religions: Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Judaism, and Christianity. That became extremely difficult at the time of India's independence from British rule. A majority of Muslims agreed with the call of their leaders, especially Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, to create a separate nation. The majority of Muslim's decided that living in cooperation with other religions, especially the dominant Hindu community, would hamstring their religious convictions. That led to the creation of Pakistan in 1947 and Bangladesh in 1971. The remnant Muslim community in India have struggled, with one degree of success or another, to cooperate

History

The emergence of Islam in the region took place at the same time as the Turko-Muslim invasion of medieval India (which includes large parts of present day Pakistan and the Republic of India). Those rulers took over the administration of large parts of India. Since its introduction into India, Islam has made significant religious, artistic, philosophical, cultural, social and political contributions to Indian history.

During the twentieth century, the Muslims of South Asia have had a turbulent history within the region. After the Lahore Resolution of 1946, Muslim League politicians established Pakistan, a Muslim-majority state, following independence from British rule. The Muslim populations of India and Pakistan number roughly the same. Former President of India, APJ Abdul Kalam, declared Islam as have two presidents before him. Numerous politicians, as well as sports and film celebrities within India, also have been Muslim. Isolated incidences of violence, nonetheless, have occurred between the Muslim populations and the Hindu, Sikh and Christian populations.

Islam arrived in South Asia long before Muslim invasions of India, the first influence came during the early seventh century with Arab traders. Arab traders visited the Malabar region, linking them with the ports of South East Asia, even before Islam established in Arabia. With the advent of Islam, Arabs became a prominent cultural force. Arab merchants and traders became the carriers of the new religion and they propagated it wherever they went. Malik Bin Deenar built the first Indian mosque in Kodungallurin 612 C.E., at the behest of Cheraman Perumal, during the life time of Muhammad (c. 571–632).[1]

In Malabar the Mappilas may have been the first community to convert to Islam. Moslems carried out intensive missionary activities along the coast, a number of natives embracing Islam. Those new converts joined the Mappila community. Thus among the Mapilas, both the descendants of the Arabs through local women and the converts from among the local people. In the eighth century, Syrian Arabs led by Muhammad bin Qasim conquered the province of Sindh (Pakistan), becoming the easternmost province of the Umayyad Caliphate. In the first half of the tenth century, Mahmud of Ghazni added the Punjab to the Ghaznavid Empire, conducting several raids deep into India. Muhammad of Ghor conducted a more successful campaign at the end of the twelfth century, leading to the creation of the Delhi Sultanate.

Islam in Kerala and Tamil Nadu

Malik Ibn Dinar and 20 other followers of Prophet Muhammad, first landed in Kodungallur in Kerala. Islam received royal patronage in some states here, and later spread to other parts of India. A local ruler gifted Dinar an abandoned Jain temple, where he established the first mosque in the Indian subcontinent in 629 C.E. Islamic scholars consider the mosque the second in the world to offer Jumma Prayer after the mosque in Medina, Saudi Arabia. His missionary team built ten additional mosques along the Malabar coast, including Kollam, Chaliyam, Pantalayini Kollam/Quilandi, Madayi/Pazhayangadi, Srikandhapuram, Dharmadom, Kasaragode,Mangalore, and Barkur. Reportedly, they built the mosques at Chombal, Kottayam, Poovar and Thengapattanam during that period.

After the fall of Chola Dynasty, the newly formed Vijayanagara Empire invited the Seljuk Turks from the fractions of Hanafi (known as Rowther in South India) for trade relations in 1279 C.E.. The largest armada of Turks traders and missionaries settled in Tharangambadi (Nagapattinam), Karaikal, Muthupet, Koothanallur and Podakkudi. Turks (Rowthers), failing to convert Hindus in Tanjore regions, settled in that area's with their armada, expanding into an Islam community of almost one million Rowthers. These new settlements were now added to the Rowther community. Hanafi fractions, more closely connected with the Turkish than others in South, have fair complexions. Some Turkish Anatolian and Turkish Safavid inscriptions have been found in wide area from Tanjore to Thiruvarur and in many villages. Madras Museum display the inscriptions to the public.

In the 1300 C.E., Arabs settled in Nagore, Kilakkarai, Adirampattinam, Kayalpatnam, Erwadi and Sri Lanka. They may have been the first Shafi fractions community of Islam, known as Marakkar, in far south and coastal areas of South India. Shafi fractions also have mixed fair and darker complexion from their close connection with the Arabs. Arab traders opened many new villages in those areas and settles, conducting intensive missionary activities along the coast. A number of natives in Malaya and Indonesia embraced Islam. Arabs (Marakkar's) missionaries married local women, converting them to Islam. The Marakkars became one of the largest Islamic communities with almost 2.5 million peoples.

Sufism and spread of Islam

Sufis played an important role in the spread of Islam in India. Their success in spreading Islam has been attributed to the parallels in Sufi belief systems and practices with Indian philosophical literature, in particular nonviolence and monism. The Sufis' unorthodox approach towards Islam made it easier for Hindus to accept the faith. Hazrat Khawaja Muin-ud-din Chisti, Nizam-ud-din Auliya, Shah Jalal, Amir Khusro, Sarkar Sabir Pak, and Waris Pak trained Sufis for the propagation of Islam in different parts of India. Once the Islamic Empire firmly established in India, Sufis invariably provided a touch of color and beauty to what might have otherwise been rather cold and stark reigns. The Sufi movement also attracted followers from the artisan and untouchable communities; they played a crucial role in bridging the distance between Islam and the indigenous traditions. Evidence of fanatical and violent conversions carried out by Sufi Muslims exists. Ahmed Sirhindi, Naqshbandi Sufi passionately advocated peaceful conversion of Hindus to Islam.

Role of Muslims in India's independence movement

The contribution of Muslim revolutionaries, poets and writers in India's struggle against the British has been documented, foremost among them Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Hakim Ajmal Khan and Rafi Ahmed Kidwai. Muhammad Ashfaq Ullah Khan of Shahjehanpur conspired to loot the British treasury at Kakori (Lucknow). Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan (popularly known as Frontier Gandhi), emerged as a great nationalist who spent forty five of his 95 years in jail. Barakatullah of Bhopal, one of the founders of the Ghadar party, helped to create a network of anti-British organizations. Syed Rahmat Shah of the Ghadar party worked as an underground revolutionary in France suffered execution by hanging for his part in the unsuccessful Ghadar (mutiny) uprising in 1915. Ali Ahmad Siddiqui of Faizabad (UP) planned the Indian Mutiny in Malaya and Burma along with Syed Mujtaba Hussain of Jaunpur, suffering execution by hanging in 1917. Vakkom Abdul Khadar of Kerala participated in the "Quit India" struggle in 1942, also hanged for his role. Umar Subhani, an industrialist and millionaire of Bombay, provided Gandhi with congress expenses and ultimately gave his life for the cause of independence. Among Muslim women, Hazrat Mahal, Asghari Begum, Bi Amma contributed in the struggle of freedom from the British.

Until the 1930s Muhammad Ali Jinnah served as a member of the Indian National Congress, taking part of the freedom struggle. Dr. Sir Allama Muhammad Iqbal, poet and philosopher, stood as a strong proponent of Hindu-Muslim unity and an undivided India until the 1920s. Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar and Maulana Shaukat Ali struggled for the emancipation of the Muslims in the overall Indian context, and struggled for freedom alongside Mahatama Gandhi and Maulana Abdul Bari of Firangi Mahal. Until the 1930s, the Muslims of India broadly conducted their politics alongside their countrymen, in the overall context of an undivided India.

In the late 1920s, recognizing the different perspectives of the Indian National Congress and that of the All India Muslim League, Dr. Sir Allama Muhammad Iqbal presented the concept of a separate Muslim homeland in India in the 1930s. Consequently, the All India Muslim League raised the demand for a separate Muslim homeland. That demand, raised in Lahore in 1940, became known as the Pakistan Resolution. Dr. Sir Allama Muhammad Iqbal had passed away by then, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, and many others led the Pakistan Movement.

Initially, the demand for separate Muslim homeland(s) fell within a framework of a large, independent, undivided India with autonomous regions governed by the Muslims. A number of other options to give the Muslim minority in India adequate protection and political representation in a free, undivided India, also came under debate. When the Indian National Congress, the All India Muslim League, and the British colonial government failed to find common ground leading to early independence of India from the British Raj, the All India Muslim League pressed unequivocally with its demand for a completely independent, sovereign country, Pakistan.

Law and politics

"The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937" governs Muslims in India[2] It directs the application of Muslim Personal Law to Muslims in marriage, mahr (dower), divorce, maintenance, gifts, waqf, wills and inheritance.[3] The courts generally apply the Hanafi Sunni law, with exceptions made only for those areas where Shia law differs substantially from Sunni practice.

Although the Indian constitution provides equal rights to all citizens irrespective of their religion, Article 44 recommends a Uniform civil code. The attempts by successive political leadership in the country to integrate Indian society under common civil code has been strongly resisted, Indian Muslims viewing that as an attempt to dilute the cultural identity of the minority groups of the country.

Muslims in modern India

Muslims in India constitute 13.4 percent of total population. Muslims have played roles in various fields of the country's advancement. Average income of Indian Muslims ranks the lowest of all Indian's religious communities.

Only four percent of Indian Muslims study in Madrasas where the primary medium of eduction is Urdu. The remaining 96 percent either attend government schools, private schools, or none according to the Sachar Committee report. The purchasing power of the Muslim community in India has been estimated at about $30 billion in 2005 (or 4 per cent of the national total). An overwhelming 131 million Muslims in India live on a per capita consumption of less than Rs.20 per day ($0.50 per day), according to the findings of the report on the [4] During the period 1975 to 2000, twenty five million Muslims belonged to the middle class in India.

Muslim institutes

There are several well established Muslim institutes in India. Universities and institutes include Aligarh Muslim University[5] (which has colleges like Deccan College of Engineering, Deccan School of Hospital Management, Deccan College of Medical Sciences), Jamia Millia Islamia, Hamdard University,[6] Maulana Azad Education Society Aurangabad, Dr. Rafiq Zakariya Campus Aurangabad,[7] Crescent Engineering College and Al-Kabir educational society. Traditional Islamic Universities include Sunni Markaz Kerala [8] (the largest charitable, non governmental, non-profit Islamic institution in India), Raza Academy,[9] Al jamiatulAshrafia, Azamgarh,[10] Darul Uloom Deoband, and Darul-uloom Nadwatul Ulama.

Population statistics

Islam represents India's largest minority religion, with 138 million people as of the 2001 census.[11] Unofficial estimates claim a far higher figure.

The largest concentrations-about 47 percent of Muslims in India, according to the 2001 census—live in the three states of Uttar Pradesh (30.7 million) (18.5 percent), West Bengal (20.2 million) (25 percent), and Bihar (13.7 million) (16.5 percent). Muslims represent a majority of the local population only in Jammu and Kashmir (67 percent in 2001) and Lakshadweep (95 percent). High concentrations of Muslims reside in the eastern states of Assam (31 percent) and West Bengal (25 percent), and in the southern state of Kerala (24.7 percent) and Karnataka (12.2 percent).

Islamic traditions in India

A majority of Muslims in India declare either Sunni Deobandi or Sunni Barelwi allegiance, although some declare allegiance to Shia, Sufi, Salafi and other smaller sects. Darul-Uloom Deoband has the most influential Islamic seminary in India, considered second only to Egypt's Al-Azhar in its global influence.

Sufism constitutes a mystical path (tarika), as distinct from the legalistic path of the sharia. A Sufi attains a direct vision of oneness with God, allowing him to become a Pir (living saint). A Pir may take on disciples (murids) and set up a spiritual lineage that can last for generations. Orders of Sufis became important in India during the thirteenth century following the ministry of Moinuddin Chishti (1142-1236), who settled in Ajmer, Rajasthan, and attracted large numbers of converts to Islam because of his holiness. His Chishtiyya order became the most influential Sufi lineage in India, although other orders from Central Asia and Southwest Asia also reached to India, playing a major role in the spread of Islam.

The most conservative wing of Islam in India has typically rested on the education system provided by the hundreds of religious training institutes (madrasa) throughout the country. The madrasa stress the study of the Qur'an and Islamic texts in Arabic and Persian, but little else. Several national movements have emerged from this sector of the Muslim community. The Jamaati Islami (Islamic Party), founded in 1941, advocates the establishment of an overtly Islamic government. The Tablighi Jamaat (Outreach Society) became active after the 1940s as a movement, primarily among the ulema (religious leaders), stressing personal renewal, prayer, a missionary spirit, and attention to orthodoxy. It has been highly critical of the kind of activities that occur in and around Sufi shrines and remains a minor, if respected, force in the training of the ulema. Conversely, other ulema have upheld the legitimacy of mass religion, including exaltation of pirs and the memory of the Prophet. A powerful secularizing drive led by Syed Ahmad Khan resulted in the foundation of Aligarh Muslim University (1875 as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College)—with a broader, more modern curriculum, than other major Muslim universities.

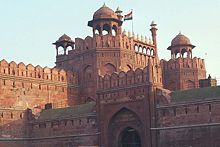

Indo-Islamic art and architecture

Indian architecture took new shape with the advent of Islamic rule in India towards the end of the twelftth century AD. Islam introduced new elements into the Indian architecture including: use of shapes (instead of natural forms); inscriptional art using decorative lettering or calligraphy; inlay decoration and use of colored marble, painted plaster and brightly colored glazed tiles.

In contrast to the indigenous Indian architecture, which utilized the trabeate order (i.e., horizontal beams spanned all spaces) the Islamic architecture practice arcuate form (i.e., an arch or dome bridges a space). Rather than creating the concept of arch or dome, Muslims borrowed and further perfected by them from the architectural styles of the post-Roman period. Muslims used a cementing agent in the form of mortar for the first time in the construction of buildings in India. They further put to use certain scientific and mechanical formulae, derived from other civilizations, in their constructions in India. Such use of scientific principles helped not only in obtaining greater strength and stability of the construction materials but also provided greater flexibility to the architects and builders.

The Islamic elements of architecture had already passed through different experimental phases in other countries like Egypt, Iran and Iraq before introduced in India. Unlike most Islamic monuments in those countries—largely constructed in brick, plaster and rubble—the Indo-Islamic monuments typical took the form of mortar-masonry works formed of dressed stones. The knowledge and skill possessed by the Indian craftsmen, who had mastered the art of stonework for centuries and used their experience while constructing Islamic monuments in India, greatly facilitated the development of the Indo-Islamic architecture.

Islamic architecture in India divides into two parts: religious and secular. Mosques and Tombs represent the religious architecture, while palaces and forts provide examples of secular Islamic architecture. Forts took an essentially functional design, complete with a little township within and various fortifications to engage and repel the enemy.

The mosque, or masjid, represents Muslim art in its simplest form. The mosque, basically an open courtyard surrounded by a pillared verandah, has a dome for a crown. A mihrab indicates the direction of the qibla for prayer. Towards the right of the mihrab stands the mimbar or pulpit from where the Imam presides over the proceedings. An elevated platform, usually a minaret from where the caller summons the faithful to attend prayers makes up an invariable part of a mosque. Jama Masjids, large mosques, assemble the faithful for the Friday prayers.

Although not actually religious in nature, the tomb or maqbara introduced an entirely new architectural concept. While the masjid exuded simplicity, a tomb ranged from a simple Aurangazeb’s grave to an awesome structure enveloped in grandeur (Taj Mahal). The tomb usually consists of a solitary compartment or tomb chamber known as the huzrah, the center serving as the cenotaph or zarih. An elaborate dome covers the entire structure. In the underground chamber lies the mortuary or the maqbara, with the corpse buried in a grave or qabr. Smaller tombs may have a mihrab, although larger mausoleums have a separate mosque located at a distance from the main tomb. Normally an enclosure surrounds the whole tomb complex or rauza. A dargah designated the tomb of a Muslim saint. Almost all Islamic monuments have verses from the Holy Koran carving in minute details on walls, ceilings, pillars and domes.

Islamic architecture in India falls into three sections: Delhi or the Imperial style (1191 to 1557 C.E.); the Provincial style, encompassing the surrounding areas like Jaunpur and the Deccan; and the Mughal style (1526 to 1707 C.E.).

See also

Islam

Islamic philosophy

Liberal movements within Islam

Pillars of Islam

Sunni Islam

Shi'a Islam

Notes

- ↑ P.A. Muhammed, Cheraman Juma Masjid A Secular Heritage. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 Vakilno1.com. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ India, Republic of Emory School of Law. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ Arjun Sengupta, Conditions of Work and Promotion of Livelihood in the Unorganised Sector. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ↑ Dar-us salam education trust. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ↑ Al- Barkaat Educational Institutions. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ↑ Al Ameen Educational Society. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ↑ Sunni Markaz Kerala. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ↑ Raza Academy. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ↑ Al jamiatulAshrafia, Azamgarh. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ↑ International Religious Freedom Report 2007 - India. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Elliot, H. M., and John Dowson. The History of India, As Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1142017057

- Majumdar, R. C. (ed.). The History and Culture of the Indian People, Volume VI. The Delhi Sultanate, Bombay, 1960: Volume VII, The Mughal Empire, Bombay, 1973.

- Mistry, M. B. "Muslims in India: A Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile." Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 25(3) (2005): 399-422.

- Nizami, Khaliq A. "Some Aspects of Khānqah Life in Medieval India." Studia Islamica 8 (1957):51–69.

- Siddiqui, M. K. A. (ed.). Marginal Muslim Communities in India. New Delhi: Institute of Objective Studies, 2004. OCLC 55961358

Gallery

- Dargah.jpg

A Huge Majority of Indian Muslims Visit Dargahs of Sufi Saints for Dua.

External links

All links retrieved April 23, 2014.

- Daily News & Views about Indian Muslims.

- India Muslims have lowest rank – BBC.

- Why India's 150m Muslims are missing out on the country's rise – Economist.

- Muslim India struggles to escape the past – Guardian.

- India's Muslim Population – Council on Foreign Relations.

- CIA's The World Factbook - India.

- Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs - Background Note: India.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.