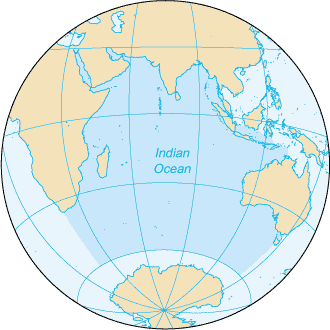

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering about 20 percent of the Earth's water surface. It is bounded on the north by Asia (including the Indian subcontinent, after which it is named); on the west by Africa; on the east by the Malay Peninsula, the Sunda Islands, and Australia; and on the south by the Southern Ocean (or, traditionally, by Antarctica). One component of the all-encompassing World Ocean, the Indian Ocean is delineated from the Atlantic Ocean by the 20° east meridian running south from Cape Agulhas,[1] and from the Pacific by the 147° east meridian. The northernmost extent of the Indian Ocean is approximately 30° north latitude in the Persian Gulf and, thus, has asymmetric ocean circulation. This ocean is nearly 10,000 kilometers (6,200 mi) wide at the southern tips of Africa and Australia; its area is 73,556,000 square kilometers (28,400,000 mi²), including the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf.

The ocean's volume is estimated to be 292,131,000 cubic kilometers (70,086,000 mi³). Small islands dot the continental rims. Island nations within the ocean are Madagascar (formerly Malagasy Republic), the world's fourth largest island; Comoros; Seychelles; Maldives; Mauritius; and Sri Lanka. Indonesia borders it. The ocean's importance as a transit route between Asia and Africa has made it a scene of conflict. Because of its size, however, no nation had successfully dominated most of it until the early 1800s when Britain controlled much of the surrounding land. Since World War II, the ocean has been dominated by India and Australia.

Geography

The African, Indian, and Antarctic crustal plates converge in the Indian Ocean. Their junctures are marked by branches of the Mid-Oceanic Ridge forming an inverted Y, with the stem running south from the edge of the continental shelf near Mumbai, India. The eastern, western, and southern basins thus formed are subdivided into smaller basins by ridges. The ocean's continental shelves are narrow, averaging 200 kilometers (125 mi) in width. An exception is found off Australia's western coast, where the shelf width exceeds 1,000 kilometers (600 mi). The average depth of the ocean is 3,890 meters (12,760 ft). Its deepest point, is in the Diamantina Deep close to the coast of south west Western Australia. North of 50° south latitude, 86% of the main basin is covered by pelagic sediments, of which more than half is globigerina ooze. The remaining 14% is layered with terrigenous sediments. Glacial outwash dominates the extreme southern latitudes.

A decision by the International Hydrographic Organization in the spring of 2000 delimited a fifth world ocean, stripping the southern portions of the Indian Ocean. The new ocean extends from the coast of Antarctica north to 60° south latitude which coincides with the Antarctic Treaty Limit. The Indian Ocean remains the third-largest of the world's five oceans.

Major chokepoints include Bab el Mandeb, Strait of Hormuz, Strait of Malacca, southern access to the Suez Canal, and the Lombok Strait. Seas include Andaman Sea, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Great Australian Bight, Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Oman, Laccadive Sea, Mozambique Channel, Persian Gulf, Red Sea, Strait of Malacca, and other tributary water bodies.

Climate

The climate north of the equator is affected by a monsoon or tornado wind system. Strong northeast winds blow from October until April; from May until October south and west winds prevail. In the Arabian Sea the violent monsoon brings rain to the Indian subcontinent. In the southern hemisphere the winds generally are milder, but summer storms near Mauritius can be severe. When the monsoon winds change, cyclones sometimes strike the shores of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. The Indian Ocean is the warmest ocean in the world.

Hydrology

Among the few large rivers flowing into the Indian Ocean are the Zambezi, Arvandrud/Shatt-al-Arab, Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Ayeyarwady River. Currents are mainly controlled by the monsoon. Two large circular currents, one in the northern hemisphere flowing clockwise and one south of the equator moving counterclockwise, constitute the dominant flow pattern. During the winter monsoon, however, currents in the north are reversed. Deepwater circulation is controlled primarily by inflows from the Atlantic Ocean, the Red Sea, and Antarctic currents. North of 20° south latitude the minimum surface temperature is 22 °C (72 °F), exceeding 28 °C (82 °F) to the east. Southward of 40° south latitude, temperatures drop quickly. Surface water salinity ranges from 32 to 37 parts per 1000, the highest occurring in the Arabian Sea and in a belt between southern Africa and southwestern Australia. Pack ice and icebergs are found throughout the year south of about 65° south latitude. The average northern limit of icebergs is 45° south latitude.

Indian Ocean Dipole

Cold water upwelling in the eastern Indian Ocean is part of a climate phenomenon called the Indian Ocean Dipole, during which the eastern half of the ocean becomes much cooler than the western half. Along with these changes in ocean temperature, strong winds blow from east to west at the equator, across Indonesia and the eastern Indian Ocean. The cool ocean temperatures begin to appear south of the island of Java in May and June along with moderate southeasterly winds. Over the next few months, both the winds and cool temperatures intensify and spread northeastward toward the equator. The southeastern Indian Ocean may become as many as 5 to 6 degrees Celsius cooler than the western part.[2]

Economy

The Indian Ocean provides major sea routes connecting the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia with Europe and the Americas. It carries a particularly heavy traffic of petroleum and petroleum products from the oilfields of the Persian Gulf and Indonesia. Large reserves of hydrocarbons are being tapped in the offshore areas of Saudi Arabia, Iran, India, and Western Australia. An estimated 40% of the world's offshore oil production comes from the Indian Ocean. Beach sands rich in heavy minerals, and offshore placer deposits are actively exploited by bordering countries, particularly India, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

The warmth of the Indian Ocean keeps phytoplankton production low, except along the northern fringes and in a few scattered spots elsewhere; life in the ocean is thus limited. Fishing is confined to subsistence levels. Its fish are of great and growing importance to the bordering countries for domestic consumption and export. Fishing fleets from Russia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan also exploit the Indian Ocean, mainly for shrimp and tuna.

Endangered marine species include the dugong, seals, turtles, and whales.

Oil pollution threatens the Arabian Sea, Persian Gulf, and Red Sea.

Threat of Global Warming

The Indian Ocean contains 16 percent of the world’s coral reefs. Global warming has been causing a steady increase in the annual peak temperatures, which is causing corals near the surface of the ocean to die off at an alarming rate. Scientists documented that 90% of the shallow corals lying from 10 to 40 meters (33ft to 130ft) below the surface of the Indian Ocean died in 1998, due to warm water temperatures, and are concerned that they will never completely recover. With global temperatures expected to rise another 2C to 2.5C this century, many scientists believe global warming is a greater threat than development or pollution. Corals are vital to the food chain and fish resources, and provide natural breakwaters which protect the shores from erosion. [3]

History

The world's earliest civilizations in Mesopotamia (beginning with Sumer), ancient Egypt, and the Indian subcontinent (beginning with the Indus Valley civilization), which began along the valleys of the Tigris-Euphrates, Nile and Indus rivers respectively, had all developed around the Indian Ocean. Civilizations soon arose in Persia (beginning with Elam) and later in Southeast Asia (beginning with Funan). During Egypt's first dynasty (c. 3000 B.C.E.), sailors were sent out onto its waters, journeying to Punt, thought to be part of present-day Somalia. Returning ships brought gold and myrrh. The earliest known maritime trade between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley (c. 2500 B.C.E.) was conducted along the Indian Ocean. Phoenicians of the late 3rd millennium B.C.E. may have entered the area, but no settlements resulted.

The Indian Ocean is far calmer, and thus opened to trade earlier, than the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans. The powerful monsoons also meant that ships could easily sail west early in the season, then wait a few months and return eastwards. This allowed Indonesian peoples to cross the Indian Ocean to settle in Madagascar.

In the second or first century B.C.E., Eudoxus of Cyzicus was the first Greek to cross the Indian Ocean. Hippalus is said to have discovered the direct route from Arabia to India around this time. During the first and second centuries intensive trade relations developed between Roman Egypt and the Tamil kingdoms of the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas in Southern India. Like the Indonesian peoples who migrated to Madagascar, the western sailors used the monsoon winds to cross the ocean. The unknown author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes this route and the ports and trade goods along the coasts of Africa and India around 70 C.E.

From 1405 to 1433, Admiral Zheng He led large fleets of the Ming Dynasty on several voyages to the Western Ocean (Chinese name for the Indian Ocean) and reached the coastal country of East Africa.

In 1497, Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and became the first European to sail to India. The European ships, armed with heavy cannon, quickly dominated trade. Portugal at first attempted to achieve pre-eminence by setting up forts at the important straits and ports. But the small nation was unable to support such a vast project, and they were replaced in the mid-seventeenth century by other European powers. The Dutch East India Company (1602-1798) sought control of trade with the East across the Indian Ocean. France and Britain established trade companies for the area. Eventually Britain became the principal power and by 1815 dominated the area.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 revived European interest in the East, but no nation was successful in establishing trade dominance. Since World War II the United Kingdom has withdrawn from the area, to be only partially replaced by India, the USSR, and the United States. The last two have tried to establish hegemony by negotiating for naval base sites. Developing countries bordering the ocean, however, seek to have it made a "zone of peace" so that they may use its shipping lanes freely, though the United Kingdom and United States maintain a military base on Diego Garcia atoll in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

On December 26, 2004, the countries surrounding the Indian Ocean were hit by a tsunami caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. The waves resulted in more than 226,000 deaths and over 1 million were left homeless.

Notes

- ↑ Limits of Oceans and Seas. International Hydrographic Organization Special Publication No. 23, 1953. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ↑ Rebecca Lindsey. A Dangerous Intersection: Humans and Climate Destroy Reef Ecosystem, April 13, 2004. Earth Observatory. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ↑ Charles Arthur. Temperature rise destroys Indian Ocean surface coral, EUROPEAN CETACEAN BYCATCH CAMPAIGN, September 18, 2003. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bose, Sugata. 2006. A hundred horizons the Indian Ocean in the age of global empire. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674021576

- Bowman, Larry W., and Ian Clark. 1981. The Indian Ocean in global politics. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. ISBN 0865310386

- Braun, Dieter. 1984. Peace in the Indian Ocean trends, developments and perspectives. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Marga Institute.

- Chaudhuri, K. N. 1985. Trade and civilisation in the Indian Ocean an economic history from the rise of Islam to 1750. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521242266

- Cousteau, Jacques Yves. 1971. Life and death in a coral sea. The Undersea discoveries of Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

- Das Gupta, Ashin, and M. N. Pearson. 1987. India and the Indian Ocean, 1500-1800. Calcutta: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195619323

- Dowdy, William L., and Russell B. Trood. 1985. The Indian Ocean; perspectives on a strategic arena. Duke Press policy studies. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0822306492

- Kerr, Alex. 1981. The Indian Ocean region resources and development. Nedlands, W.A.: University of Western Australia Press. ISBN 0865311234

- Krauss, Erich. 2006. Wave of destruction the stories of four families and history's deadliest tsunami. [Emmaus, Pa.]: Rodale. ISBN 1594863784

- Metz, Helen Chapin. 1995. Indian Ocean five island countries. Area handbook series. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844408573

- Nairn, A. E. M., and Francis Greenough Stehli. 1973. The ocean basins and margins. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0306377713

- Ostheimer, John M. 1975. The Politics of the Western Indian Ocean Islands.

- Torabully, Khal. 2002. Coolitude: An Anthology of the Indian Labour Diaspora. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 1843310031

- Toussaint, Auguste. Trans. by June Guicharnaud. 1966. The History of the Indian Ocean.

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Much of this text is based on public domain text by US Naval Oceanographer at: http://oceanographer.navy.mil/indian.html